Abstract

Pancreatic cysts represent a small proportion of pancreatic diseases, but their incidence has been recently increasing. Most pancreatic cysts are identified incidentally, causing a dilemma for both clinicians and patients. In contrast to ductal adenocarcinoma, neoplastic pancreatic cysts may be cured by resection. In general, pancreatic cysts are classified as neoplastic or non-neoplastic cysts. The predominant types of neoplastic cysts include intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms, mucinous cystic neoplasms, serous cystic neoplasms, and solid pseudopapillary neoplasms. With the exception of serous type, neoplastic cysts, have malignant potential, and in most cases requires resection. Non-neoplastic cysts include pseudocyst, retention cyst, benign epithelial cysts, lymphoepithelial cysts, squamous lined cysts (dermoid cyst and epidermal cyst in intrapancreatic accessory spleen), mucinous nonneoplastic cysts, and lymphangiomas. The incidence of nonneoplastic, noninflammatory cysts is about 6.3% of all pancreatic cysts. Despite the use of high-resolution imaging technologies and cytologic tissue acquisition with endosonography, distinguishing nonneoplastic from neoplastic cysts remains difficult with most differentiations made postoperatively. Nonetheless, the definitive distinction between non-neoplastic and neoplastic cysts is crucial as unnecessary surgery could be avoided with proper diagnosis. Therefore, consideration of these rare disease entities should be entertained before deciding on surgery.

Pancreatic cysts represent a small proportion of pancreatic lesions.1 Most Pancreatic cysts (71%) are asymptomatic and found incidentally.2 The prevalence of these lesions detected on abdominal imaging is 2.6%, while it is 8% in the elderly3 and was approximately 13.5% in a study of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for nonspecific symptoms.4 Pancreatic cysts are also found in up to 25% of autopsied individuals.5 Recently the prevalence of pancreatic cysts is increasing owing to advances in imaging technologies and the widespread use of high-resolution imaging.6,7,8,9

In general, pancreatic cysts are classified into neoplastic and nonneoplastic cysts.1,10,11 Neoplastic cysts are broadly categorized as serous or mucinous.1 Serous cystic neoplasms are considered to be benign; however, mucinous cystic neoplasms (MCNs) which include intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMNs) and MCNs are considered to have a malignant potential. Nonneoplastic cysts are benign lesions that can be further classified as either nonepithelial or epithelial.1,12,13,14 Pseudocysts and infection-related cysts are typical nonneoplastic, nonepithelial cysts. Nonneoplastic cysts, including epithelial cysts, retention cysts, squamoid cysts, mucinous nonneoplastic cysts (MNCs), enterogenous cysts, lymphoepithelial cysts (LECs), and endometrial cyst,12,13,14 accounted for 6.3% of all resected cysts in a recent study.1

Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography are commonly used to evaluate pancreatic cysts, but both imaging modalities are occasionally characterized by difficulties when applied for detailed assessment and adequate characterization of pancreatic cysts. Diagnoses of main-duct IPMN or serous cystic denoma are thought to be almost correct with conventional imaging tools, but the accuracy of preoperative diagnosis with conventional imaging tools was found to be only 68% in one study.7,15,16 Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) has recently been widely applied for evaluation of pancreatic cysts because of its better imaging resolution and ability to provide cytologic and biochemical analysis.6,7,9,10,15,17,18 Although nonneoplastic entities comprise a small portion of pancreatic cysts, distinguishing nonneoplastic cysts from neoplastic cysts is quite important. Despite the rarity of nonneoplastic cysts, it is important to recognize their existence and presentation pattern to avoid surgical treatment when possible.

In this article, several rare, nonneoplastic pancreatic cysts mimicking neoplastic pancreatic cysts are briefly reviewed.

Retention cysts are defined as cystic dilations of the pancreatic duct due to intraluminal obstruction.1 Retention cysts are congenital or secondary to obstructions caused by calculi, mucin, chronic pancreatitis, or pancreatic adenocarcinoma.11,14 Their mucosal linings are known to be mucinous. While small fluid loculations are common features of retention cysts, their appearance sometimes overlaps with that of IPMN if the intraluminal obstruction develops proximal to the pancreatic duct.19 Incorporating MNCs into differential diagnoses is important because both lesions have the similar mucinous mucosal lining. Absence of ductal obstructions can aid in differential diagnosis.11 Imaging features of both retention cysts and IPMN are similar and these findings might to lead to unnecessary operation (Figs. 1,2,3).

Dermoid cysts in the pancreas are rare and is a teratomatous neoplasm containing squamous, sebaceous, and/or respiratory epithelium and hair follicles.20 Clinical presentation is nonspecific. These cysts are frequently appeared in younger patients. No gender preference was reported.21 No pathognomonic data is known on imaging studies such as transabdominal sonography, CT and MRI for their preoperative recognition.21 Histologic evaluation has revealed rare diagnoses of dermoid cysts. Recently the availability of EUS-guided fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) has been presented as a valuable diagnostic adjunct for preoperative evaluation of patients with dermoid cysts.22 To date, treatment of dermoid cysts has consisted of surgical removal, and conservative treatment has not been described in most cases. However, if apt diagnoses were made, resection of dermoid cysts would be avoided.21

LECs of the pancreas are extremely rare, nonneoplastic, intrapancreatic or peripancreatic keratinizing cysts with surrounding stroma that resemble lymph nodes.20 LECs are lined by a stratified squamous epithelium and contain subepithelial lymphoid tissue and follicles.14 In 1985, Lüchtrath and Schriefers23 first described the distinctive morphological features of LECs, which were similar to the branchial cleft cysts of the lateral neck. The term "LEC of the pancreas" was proposed by Truong et al.24 in 1987.

LECs, which comprise about 0.5% of all pancreatic cysts, predominantly occur in middle-aged men (mean age, 55; M:F, 4:1). LECs have well-delineated multilocular (60%) or unilocular (40%) masses of variable size, ranging from about 1 to >15 cm.25 The cyst contents vary from serous to caseous-like, depending on the degree of keratin formation.26 The largest series in the surgical pathology literature was reported by Adsay et al.27 and included a total of 12 patients. Because of their rarity, the cytologic features of LECs have been described in small case reports. It occurs at any age and no gender preference was reported. The pathogenesis of LECs is imprecise. One theory suggests an origin from misplaced brachial cleft tissue, because the two lesions histologically resemble one another.8 Another theory suggests they originated from squamous metaplasia of an obstructed pancreatic duct, which subsequently protrudes into a peripancreatic lymph node.24,25 Finally, some investigators have suggested that cysts develop from ectopic pancreatic tissue in peripancreatic lymph nodes.24 This theory would explain the often extrinsic location of the lesions and the fact that pancreatic tissue can be found throughout these lesions.28 Furthermore, benign ectopic pancreatic tissue has been reported in peripancreatic lymph nodes.29 In contrast to LECs of the head and neck, which are frequently associated with viral or systemic illness, there has been no recorded evidence of such diseases with pancreatic LECs.8 The lesions are not believed to be neoplastic, and no malignant behavior has been recorded to date. Additionally, there have been no reports of LECs becoming malignant or recurring after surgical resection. LECs have appeared as both multilocular and unilocular cysts. No characteristic findings of conventional imaging tools like transabdominal sonography or abdominal CT scan. However, recent evidence suggests that MRI with a high signal on T1-weighted images and a low signal on T2 images, which reflects the keratin content of the cysts, may facilitate correct diagnosis of LECs.30 In an EUS case series conducted by Nasr et al.,31 pancreatic LECs commonly appeared as solid, hyperechoic, heterogeneous masses with subtle postacoustic enhancement. Occasionally, fine or coarse sludge like hyperechoic echo architecture was also seen, which was likely due to debris within the cyst.

The first description of cytologic findings of LECs was published by Mitchell32 in 1990. The FNA samples typically showed abundant, anucleated squamous cells with few benign-appearing nucleated squamous cells, debris (keratinous and amorphous), occasional multinucleated giant cells and cholesterol crystals.8 FNA is the only tool for diagnosis of LECs when keratinizing squamous epithelium and lymphoid tissue are observed; however, the specificity and sensitivity of FNA remains poor; the detection of LEC was occurred in almost half of all cases to which FNA has been applied.30

Pseudocysts and cystic neoplasms of the pancreas are differential diagnoses of LEC. Lack of squamous epithelium in the aspirate from pseudocysts and elevation of amylase with low carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels are essential to differential diagnosis. Aspirates from mucinous cysts usually show background extracellular mucus with or without mucinous epithelium. However, the degenerated squamous material of LECs may be misinterpreted as mucoid material.8,33 Chemical analysis of pancreatic LECs fluid has rarely been reported. Occasional elevation of CEA and CA 19-9 could lead to false diagnosis of mucinous neoplasms, especially because EUS-guided FNA samples may show both squamous and glandular contaminants.34 However, the presence of abundant anucleated squamous epithelium should favor a diagnosis of pancreatic LEC.

If the patient is asymptomatic and EUS-FNA firmly established the diagnosis of LEC based on cytological examination of the cyst fluid, surgery can be avoided and the patient may be followed with serial cross-sectional imaging of the upper abdomen.35 Because the absence of cytological proof of LECs, even with high cystic fluid CEA and CA 19-9 levels, does not completely exclude LEC diagnosis, surgical resection is considered when making a confident preoperative diagnosis (Figs. 4,5,6).

Epidermoid cyst arising from an intrapancreatic accessory spleen (ECIPAS) is a rare pancreatic cyst characterized by nonneoplastic keratinizing epithelium surrounded by splenic parenchyma.20 Most ECIPAS was found incidentally for the evaluation of unrelated medical conditions. In some patients, the elevation of serum CA 19-9 which causes the confusion on malignancy was observed. The reason for the elevation of serum CA 19-9 was explained by the presence of squamous epithelial lining of the epidermoid cyst.36,37 Three theories were suggested as the origin of the cystic epithelium of an ECIPAS.38 The first theory suggests that the lesions arise from a pancreatic duct protruding into an intrapancreatic accessory spleen. The second suggests an origin from a mesothelial inclusion with subsequent squamous metaplasia. The third suggests a teratomatous derivation or inclusion of fetal squamous epithelium. Because the ECIPAS is frequently misdiagnosed as other neoplastic cysts such as MCN, IPMN or infrequently neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas, the crucial issue regarding ECIPAS in clinical practice lies on how to appropriately differentiate these lesions from other cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. On account of similarity in radiologic findings between an ECIPAS and other pancreatic cystic neoplasms, histologic diagnosis as well as imaging studies is demanded for differential diagnosis. However, the role of EUS-FNA in diagnosing ECIPAS has been limited. In general, cytologic analysis of the cystic fluid is nonspecific, revealing macrophages and scattered small lymphocytes suggestive of cysts.39 The fluid CEA levels are usually elevated, and sometimes may be very high,40 which could lead to misdiagnosis as having MCN or IPMN of the pancreas. Though the results of EUS-FNA on ECIPAS are still not acceptable so far, the proper diagnosis of an ECIPAS might be possible with an adequate amount of tissue acquisition including spleen tissue by EUS-FNA. Correct diagnosis of ECIPAS can lead to conservative management (Figs. 7,8,9).

In 2007, Othman et al.40 reported a new type of squamous-lined pancreatic cyst termed squamoid cyst of pancreatic ducts (SCOP). Both metaplastic squamous/transitional transformation and cystic dilation of the pancreatic ducts are the characteristics of these cysts.40 SCOP are variably lined by flat, transitional, and stratified squamous epithelial cells that lack a granular cell layer and orthokeratosis or parakeratosis40 Localized ductal obstruction was suggested as an etiology of these cysts because unilocular dilatation and metaplasia of pancreatic ducts with the presence of chronic pancreatitis and a traumatic neuroma are observed in these lesions.20

Histologically, the band of dense lymphoid tissue seen in LECs is absent from squamoid cysts. The absence of mucinous epithelium can be used to distinguish retention cysts from squamoid cysts. Additionally, nuclear p63 expression, a marker of squamous/transitional epithelium in nonneoplastic epithelial cysts, can be found in the basal layers of the cyst lining upon immunohistochemical staining.40 In addition, all squamoid cysts reported to date have expressed the intercalated duct centroacinar cell markers MUC1 and MUC6.40 Nevertheless, squamoid cysts are often mistaken preoperatively for potentially malignant lesions such as MCNs.

Foo et al.20 reported a rare case of multifocal cystic dilation and squamoid metaplasia of the distal pancreatic duct system, suggesting an extreme variant of SCOP, which they termed squamoid cystosis of pancreatic ducts. In their report, marked chronic pancreatitis around the involved ducts and a small traumatic neuroma near the junction between the affected and unaffected pancreatic parenchyma were revealed.

The term mucinous nonepithelial cyst was first described by Kosmahl et al.41 in 2002. They reported five cases of a novel nonneoplastic cystic change in pancreas. This benign cyst is lined with a monolayer of cuboidal to columnar mucinous epithelium and appears as unilocular or multilocular. Communication with the pancreatic duct has not been observed.

The pathology of MNCs are characterized by mucinous differentiation of the lining epithelium, lack of cellular atypia or increased proliferation, a thin rim of almost acellular supporting stroma and the absence of communication with the pancreatic ducts.41 MNCs are considered benign and have not been found to demonstrate any neoplastic features such as dysplasia, proliferative activity, invasive growth patterns, or metastatic spread to date.

The incidence of MNCs is 2.1% to 3.4% in resected pancreatic lesions. MNCs are found over a wide age range (20 to 88 years), but tend to be more common in females over 50 years of age.42 Pancreas head (65%, 13/20) is the most frequently location of MNCs. Most MNCs present as a single cyst (70%, 14/20), with only 30% presenting with multiple lesions.42 Finally, most MNCs have been found incidentally and their clinical presentations are usually nonspecific. The pathogenesis of MNCs is unclear. Cao et al.43 proposed that they might be related to acinar-ductal mucinous metaplasia. The key clinicopathological features of MNCs include: (1) mucinous differentiation of the lining epithelium; (2) lack of cellular atypia or increased proliferation; (3) a thin rim of supporting, almost acellular stroma; (4) lack of communication with the duct or biliary system; and (5) preferential localization in the pancreatic head.41 It is currently not clear if these cysts are entirely benign or represent the earliest elements of the neoplastic spectrum, which is seen in most mucinous cysts. In the case of MNC, it is clear that further molecular analysis must be pursued to assess this novel lesion's place on the spectrum of adenoma to carcinoma.44 MNCs represent a diagnostic challenge, as they often mimic IPMNs and MCNs clinically and radiographically. EUS-FNA obtained cyst fluid often demonstrates elevated CEA levels, making differentiation between benign and premalignant lesions difficult.44 The absence of characteristic ovarian type stroma can be used to distinguish MCNs from MNCs, and absence of pancreatic ductal communication can exclude IPMNs from MNCs. Atypical epithelial cells, if present, favor neoplastic mucinous cystic lesions and may be a marker to exclude MNCs. A recent study reported that MNCs have a positive apomucin phenotype, which may distinguish them from IPMNs.43,44 Nevertheless, these analyses can only be carried out on postoperative gross specimens, and are not useful for preoperative diagnosis.

In a previous investigation of mucin expression in MNCs, expression of Muc 5Ac and Muc1 was reported in 14 of 20 (70%) and five of 20 cases (25%), respectively. Expression of Muc2 was not observed in any of these cases.41,43 The images of MNCs upon MRI may be indistinguishable from that of MCNs, especially if the cysts are large and have thick walls. FNA cytology of the epithelium of MNCs shares that of retention cysts. Retention cysts can be excluded based on the absence of potential causes or evidence of ductal obstructions; however, this is not always possible. Nonetheless, although EUS-FNA could not distinguish MNCs from retention cysts, treatment and prognosis will not be affected owing to the benign nature of both diseases.6 If the diagnosis of MNCs is doubtful, surgical resection is a reasonable strategy (Figs. 10,11,12).

Lymphangiomas are rare, benign, and congenital malformations of the lymphatic systems.45 Most lymphangiomas occur in the neck (75%) and axillary regions (25%),46 while lymphangiomas of the pancreas are extremely rare, accounting for only 1% of all occurrences.47 Pancreatic lymphangiomas are predominantly found in women, with a female:male ratio of approximately 2:1.48 The average age at presentation is 25.6 years, and most patients are asymptomatic. In the only histologic study of pancreatic lymphangiomas conducted to date, the characteristic histological features included multiple cystic spaces lined by flattened endothelial cells, irregularly distributed smooth muscle cells, and lymphoid aggregates in the walls of the cysts.48 Although the pathogenesis of lymphangiomas is still unclear, a well-established theory suggests that lymphangiomas arise from sequestrations of lymphatic tissue during embryonic development.49 However, it has been suggested that abdominal trauma, lymphatic obstruction, inflammatory processes, surgery or radiation therapy lead to the secondary formation of lymphangiomas.50 A diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lymphangioma is made if the aspirated fluid is chylous in appearance and has an elevated triglyceride level.51 If the fluid aspirated is serous and has only a mildly elevated triglyceride level, then further diagnostic workup or surgical referral may be necessary.52

No malignant transformation of pancreatic cystic lymphangiomas has been reported to date. Expectant management with follow-up is a reasonable approach; however, the possibility remains for hemorrhage, torsion, rupture, obstruction and infection in these patients, especially in the setting of any abdominal trauma. This potential should be weighed against the risks of surgery, which by most reports is curative.53

Nonneoplastic pancreatic cysts are rarely encountered disease entities. Furthermore, some other rare nonneoplastic pancreatic cysts were not reviewed in this article such as benign epithelial cysts and duodenal wall cysts (diverticula). The cliniacl signficance of these cysts obviously underlies their benign nature. However, despite advances in radiographic and minimally invasive diagnostic procedures such as EUS-FNA, it is not always possible to distinguish nonneoplastic pancreatic cysts from their neoplastic counterparts. Nevertheless, clinicians should be familiar with these rare disease entities, and all available efforts should be exerted to distinguish these benign nonneoplastic cysts from neoplastic cysts with malignant potential before development of therapeutic strategies. Better understanding of these nonneoplastic cysts might enable unnecessary surgery to be avoided.

References

1. Assifi MM, Nguyen PD, Agrawal N, et al. Non-neoplastic epithelial cysts of the pancreas: a rare, benign entity. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014; 18:523–531. PMID: 24449000.

2. Ferrone CR, Correa-Gallego C, Warshaw AL, et al. Current trends in pancreatic cystic neoplasms. Arch Surg. 2009; 144:448–454. PMID: 19451487.

3. Laffan TA, Horton KM, Klein AP, et al. Prevalence of unsuspected pancreatic cysts on MDCT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008; 191:802–807. PMID: 18716113.

4. Lee KS, Sekhar A, Rofsky NM, Pedrosa I. Prevalence of incidental pancreatic cysts in the adult population on MR imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:2079–2084. PMID: 20354507.

5. Kimura W, Nagai H, Kuroda A, Muto T, Esaki Y. Analysis of small cystic lesions of the pancreas. Int J Pancreatol. 1995; 18:197–206. PMID: 8708390.

6. Zhu B, Keswani RN, Lin X. Fine needle aspiration cytomorphology of mucinous nonneoplastic cyst of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2013; 42:27–31. PMID: 22750967.

7. Khashab MA, Kim K, Lennon AM, et al. Should we do EUS/FNA on patients with pancreatic cysts? The incremental diagnostic yield of EUS over CT/MRI for prediction of cystic neoplasms. Pancreas. 2013; 42:717–721. PMID: 23558241.

8. Policarpio-Nicolas ML, Shami VM, Kahaleh M, et al. Fine-needle aspiration cytology of pancreatic lymphoepithelial cysts. Cancer. 2006; 108:501–506. PMID: 17063496.

9. Okabe Y, Kaji R, Ishida Y, Tsuruta O, Sata M. The management of the pancreatic cystic: neoplasm: the role of the EUS in Japan. Dig Endosc. 2011; 23(Suppl 1):39–42. PMID: 21535199.

10. Lee LS. Diagnostic approach to pancreatic cysts. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014; 30:511–517. PMID: 25003604.

11. Goh BK, Tan YM, Tan PH, Ooi LL. Mucinous nonneoplastic cyst of the pancreas: a truly novel pathological entity? World J Gastroenterol. 2005; 11:2045–2047. PMID: 15801005.

12. Kosmahl M, Pauser U, Peters K, et al. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas and tumor-like lesions with cystic features: a review of 418 cases and a classification proposal. Virchows Arch. 2004; 445:168–178. PMID: 15185076.

13. Parra-Herran CE, Garcia MT, Herrera L, Bejarano PA. Cystic lesions of the pancreas: clinical and pathologic review of cases in a five year period. JOP. 2010; 11:358–364. PMID: 20601810.

14. Molvar C, Kayhan A, Lakadamyali H, Oto A. Nonneoplastic cystic lesions of pancreas: a practical clinical, histologic, and radiologic approach. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2011; 40:141–148. PMID: 21616276.

15. Koito K, Namieno T, Nagakawa T, Shyonai T, Hirokawa N, Morita K. Solitary cystic tumor of the pancreas: EUS-pathologic correlation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997; 45:268–276. PMID: 9087833.

16. Jani N, Bani Hani M, Schulick RD, Hruban RH, Cunningham SC. Diagnosis and management of cystic lesions of the pancreas. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2011; 2011:478913. PMID: 21904442.

17. Karim Z, Walker B, Lam E. Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas: the use of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in diagnosis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2010; 24:348–350. PMID: 20559575.

18. Zhu LC, Grieco V. Diagnostic value of unusual gross appearance of aspirated material from endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration of pancreatic and peripancreatic cystic lesions. Acta Cytol. 2008; 52:535–540. PMID: 18833814.

19. Goh BK, Tan YM, Chung YF, et al. Non-neoplastic cystic and cystic-like lesions of the pancreas: may mimic pancreatic cystic neoplasms. ANZ J Surg. 2006; 76:325–331. PMID: 16768691.

20. Foo WC, Wang H, Prieto VG, Fleming JB, Abraham SC. Squamoid cystosis of pancreatic ducts: a variant of a newly-described cystic lesion, with evidence for an obstructive etiology. Rare Tumors. 2014; 6:5286. PMID: 25276318.

21. Tucci G, Muzi MG, Nigro C, et al. Dermoid cyst of the pancreas: presentation and management. World J Surg Oncol. 2007; 5:85. PMID: 17683548.

22. Markovsky V, Russin VL. Fine-needle aspiration of dermoid cyst of the pancreas: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 1993; 9:66–69. PMID: 8458286.

23. Lüchtrath H, Schriefers KH. A pancreatic cyst with features of a so-called branchiogenic cyst. Pathologe. 1985; 6:217–219. PMID: 4048076.

24. Truong LD, Rangdaeng S, Jordan PH Jr. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 1987; 11:899–903. PMID: 3674287.

25. Adsay NV, Hasteh F, Cheng JD, Klimstra DS. Squamous-lined cysts of the pancreas: lymphoepithelial cysts, dermoid cysts (teratomas), and accessory-splenic epidermoid cysts. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000; 17:56–65. PMID: 10721807.

26. Volkan Adsay N. Cystic lesions of the pancreas. Mod Pathol. 2007; 20(Suppl 1):S71–S93. PMID: 17486054.

27. Adsay NV, Hasteh F, Cheng JD, et al. Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas: a report of 12 cases and a review of the literature. Mod Pathol. 2002; 15:492–501. PMID: 12011254.

28. Capitanich P, Iovaldi ML, Medrano M, et al. Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas: case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004; 8:342–345. PMID: 15019932.

29. Murayama H, Kikuchi M, Imai T, Yamamoto Y, Iwata Y. A case of heterotopic pancreas in lymph node. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol. 1978; 377:175–179. PMID: 147560.

30. Mege D, Grégoire E, Barbier L, Del Grande J, Le Treut YP. Lymphoepithelial cyst of the pancreas: an analysis of 117 patients. Pancreas. 2014; 43:987–995. PMID: 25207659.

31. Nasr J, Sanders M, Fasanella K, Khalid A, McGrath K. Lymphoepithelial cysts of the pancreas: an EUS case series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 68:170–173. PMID: 18513719.

32. Mitchell ML. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of peripancreatic lymphoepithelial cysts. Acta Cytol. 1990; 34:462–463. PMID: 2343707.

33. Mandavilli SR, Port J, Ali SZ. Lymphoepithelial cyst (LEC) of the pancreas: cytomorphology and differential diagnosis on fine-needle aspiration (FNA). Diagn Cytopathol. 1999; 20:371–374. PMID: 10352910.

34. Ahlawat SK. Lymphoepithelial cyst of pancreas. Role of endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration. JOP. 2008; 9:230–234. PMID: 18326936.

35. Anagnostopoulos PV, Pipinos II, Rose WW, Elkus R. Lymphoepithelial cyst in the pancreas: a case report and review of the literature. Dig Surg. 2000; 17:309–314. PMID: 10867475.

36. Hwang HS, Lee SS, Kim SC, Seo DW, Kim J. Intrapancreatic accessory spleen: clinicopathologic analysis of 12 cases. Pancreas. 2011; 40:956–965. PMID: 21562442.

37. Higaki K, Jimi A, Watanabe J, Kusaba A, Kojiro M. Epidermoid cyst of the spleen with CA19-9 or carcinoembryonic antigen productions: report of three cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22:704–708. PMID: 9630177.

38. Hu S, Zhu L, Song Q, Chen K. Epidermoid cyst in intrapancreatic accessory spleen: computed tomography findings and clinical manifestation. Abdom Imaging. 2012; 37:828–833. PMID: 22327420.

39. Reiss G, Sickel JZ, See-Tho K, Ramrakhiani S. Intrapancreatic splenic cyst mimicking pancreatic cystic neoplasm diagnosed by EUS-FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 70:557–558. PMID: 19608182.

40. Othman M, Basturk O, Groisman G, Krasinskas A, Adsay NV. Squamoid cyst of pancreatic ducts: a distinct type of cystic lesion in the pancreas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31:291–297. PMID: 17255775.

41. Kosmahl M, Egawa N, Schröder S, Carneiro F, Lüttges J, Klöppel G. Mucinous nonneoplastic cyst of the pancreas: a novel nonneoplastic cystic change? Mod Pathol. 2002; 15:154–158. PMID: 11850544.

42. Yang JD, Song JS, Noh SJ, Moon WS. Mucinous non-neoplastic cyst of the pancreas. Korean J Pathol. 2013; 47:188–190. PMID: 23667381.

43. Cao W, Adley BP, Liao J, et al. Mucinous nonneoplastic cyst of the pancreas: apomucin phenotype distinguishes this entity from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Hum Pathol. 2010; 41:513–521. PMID: 19954814.

44. Nadig SN, Pedrosa I, Goldsmith JD, Callery MP, Vollmer CM. Clinical implications of mucinous nonneoplastic cysts of the pancreas. Pancreas. 2012; 41:441–446. PMID: 22015974.

45. Koenig TR, Loyer EM, Whitman GJ, Raymond AK, Charnsangavej C. Cystic lymphangioma of the pancreas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001; 177:1090. PMID: 11641176.

46. Igarashi A, Maruo Y, Ito T, et al. Huge cystic lymphangioma of the pancreas: report of a case. Surg Today. 2001; 31:743–746. PMID: 11510617.

47. Paal E, Thompson LD, Heffess CS. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of ten pancreatic lymphangiomas and a review of the literature. Cancer. 1998; 82:2150–2158. PMID: 9610694.

48. Gui L, Bigler SA, Subramony C. Lymphangioma of the pancreas with "ovarian-like" mesenchymal stroma: a case report with emphasis on histogenesis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003; 127:1513–1516. PMID: 14567749.

49. Kim HH, Park EK, Seoung JS, et al. Cystic lymphangioma of the pancreas mimicking pancreatic pseudocyst. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011; 80(Suppl 1):S55–S58. PMID: 22066085.

50. Schneider G, Seidel R, Altmeyer K, et al. Lymphangioma of the pancreas and the duodenal wall: MR imaging findings. Eur Radiol. 2001; 11:2232–2235. PMID: 11702164.

51. Jathal A, Arsenescu R, Crowe G, Movva R, Shamoun DK. Diagnosis of pancreatic cystic lymphangioma with EUS-guided FNA: report of a case. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 61:920–922. PMID: 15933705.

52. Coe AW, Evans J, Conway J. Pancreas cystic lymphangioma diagnosed with EUS-FNA. JOP. 2012; 13:282–284. PMID: 22572132.

53. Sanaka MR, Kowalski TE. Cystic lymphangioma of the pancreas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 5:e10–e11. PMID: 17368224.

Fig. 2

A 1.6 cm anechoic cystic lesion with peripheral hyperechoic spots suggestive of debris on endoscopic ultrasound.

Fig. 4

A large cyst with thin wall and peripheral calcified lesions was revealed on abdominal computed tomography scan.

Fig. 5

A large cyst measuring 6 cm with inhomogeneous internal echogenicity was observed on endoscopic ultrasound.

Fig. 8

An arrow showed a small homogeneous hypoechoic lesion in pancreas tail on endoscopic ultrasound.

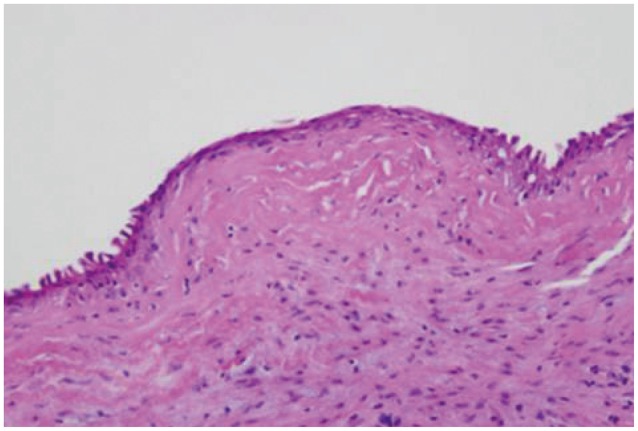

Fig. 9

Histologic finding of epidermoid cyst arising from an intrapancreatic accessory spleen showed a stratified mucosal epithelium (H&E stain, ×100).

Fig. 10

Abdominal computed tomography scan showed 4 cm sized well-demarcated low density cystic lesion in pancreas head.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download