This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Diagnostic upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the most basic of endoscopy procedures and is the technique that trainee doctors first learn. Mastering the basics of endoscopy is very important because when this process is imprecise or performed incorrectly, it can severely affect a patient's health or life. Although there are several guidelines and studies that consider these basics, there are still no standard recommendations for endoscopy in Korea. In this review, basic points, including proper endoscope insertion, precise observation without blind spots, and appropriate photographing, for upper gastrointestinal endoscopy will be discussed.

Go to :

Keywords: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, Insertion, Observation, Photographing

INTRODUCTION

Due to the recent increased interest in health and the National Cancer Screening Project, the demand for upper and lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy procedures is rapidly increasing. Accordingly, many doctors are enrolling in training courses to obtain an endoscopy specialist license. Diagnostic upper GI endoscopy is the most basic among endoscopy procedures and is the technique that trainee doctors first learn. Although this applies to a training course in any field, mastering endoscopy basics is very important because when the process is imprecise or incorrectly performed, it can cause severe complications, endangering the patient's health or life.

123

Insertion of the endoscope through the oral cavity and pharynx into the esophagus is the most difficult part of the process for trainee doctors. Incorrect technique can cause serious complications. Once the endoscope is inserted, detailed observation without blind spots is essential for a perfect procedure. Quality control in endoscopy procedures has recently come under heavy discussion;

4567 as such, the storage of endoscopy data, and photo images in particular, is very important. Specifically, when a patient is transferred for the treatment of a discovered lesion, photo images can be a very useful tool for exchanging opinions between doctors. Photo images are also useful in observing lesion changes during follow-up endoscopy, in educating trainee doctors, or in securing evidence in preparation for the remote possibility of a medical claim. A few guidelines and studies consider these factors,

89101112 but there are still no standard recommendations in Korea. Consequently, in this review, I aim to investigate proper endoscope insertion, techniques to perform precise observation without blind spots, and appropriate photographing for upper GI endoscopy.

Go to :

PROPER INSERTION

One of the most difficult things for inexperienced endoscopists is endoscope insertion. Although several endoscopy-related texts are available, few give detailed guidance on insertion methods. One website, although not published literature, is well organized and contains content based on extensive experience and the opinions of several experts, to which I refer here.

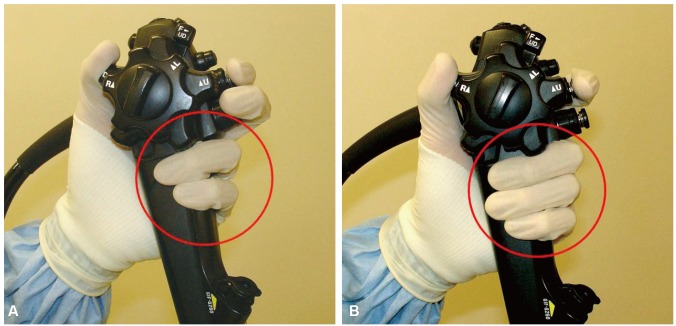

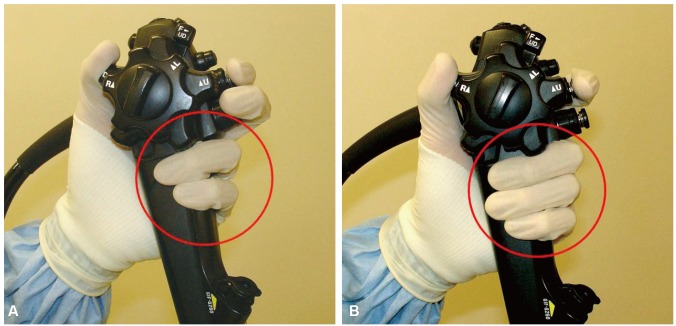

13 The most important point for proper insertion is for the operator to have a stable posture. Although the method of gripping the endoscope is not thought to directly affect procedural results, long-term continued use of a grip that is not suited to the operator can cause problems in the finger joints and prevent a stable examination. Commonly used endoscope grips include the two-finger method, in which the ring and little fingers hold the endoscope and the index and middle fingers operate the suction and aspiration valves, or the three-finger method, in which the middle, ring, and little fingers hold the endoscope and only the index finger is used for the suction and aspiration valves (

Fig. 1). For operators with small hands, because the two-finger method leads to insufficient endoscope stability and can easily cause problems of the wrist and arm, the three-finger method is more appropriate. In the three-finger method, temporary switching to the two-finger method is simple for when the two valves have to be used at the same time.

| Fig. 1Grips in the endoscopic procedure. (A) Two-finger method, in which the ring and little fingers hold the endoscope and the index and middle fingers operate the suction and aspiration valves. (B) Three-finger method, in which the middle, ring, and little fingers hold the endoscope and only the index finger is used for the suction and aspiration valves. Adapted from Lee,13 with permission from EndoTODAY.

|

During endoscope insertion, the insertion tube should be held lightly with the ends of the fingers of the right hand and proceed so almost no resistance is felt from the distal end. If the tube is pushed excessively despite resistance, it can cause pharyngeal perforation near the pharynx or severe submucosal hemorrhage, so care must be taken. At this time, the operator should hold the endoscope in the right hand 25 to 30 cm from the distal end. If held too close, the right hand must be moved before the endoscope enters the upper esophagus; conversely, if held too far, endoscopic maneuverability is negatively affected.

As the endoscope passes the tongue but before it enters the pharynx, the left thumb is used to turn the large knob on the control body downward to deflect it upward by approximately 60°. This is because the path from the lips, over the tongue, through the pharynx, and into the esophagus is curved. If the endoscope is inserted without use of this process, it will severely irritate the soft palate. For beginners who are not familiar with maneuvering an endoscope, it is useful to bend the upper body to the height of the patient's mouth and directly observe as the distal end of the endoscope arrives at the soft palate. Once the operator has become somewhat familiar with endoscopy, it should be possible to pass the soft palate and pharynx and arrive at the left pyriform sinus without difficulty by watching the screen and not bending over. When the tip of the endoscope arrives at the posterior wall of the pharynx, it should be gently released slightly from its upward deflection; if this is not done and the endoscope continues to be inserted, it will approach the larynx.

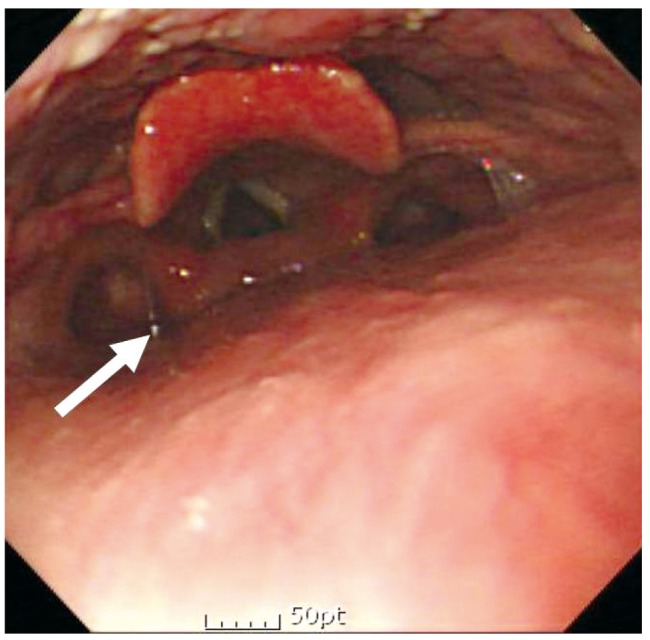

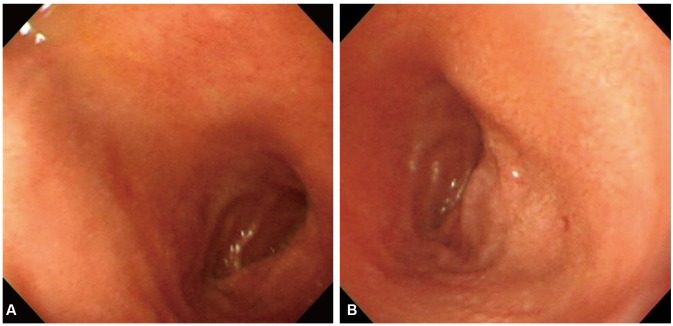

When the endoscope arrives at the left pyriform sinus as seen on the left side of the screen, its tip is maneuvered so that it faces the center and the endoscope is carefully inserted (

Fig. 2). At this time, the knob on its control body can be used, but otherwise, if the endoscope is turned slightly clockwise and the left arm is raised, it will naturally face the center. It is usually possible to insert the endoscope through the left pyriform sinus without difficulty, but if resistance is felt, insertion through the right pyriform sinus could be attempted. If the endoscope cannot be passed even after several attempts, a method in which the patient is asked to swallow and the endoscope is gently inserted when the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes could be attempted.

| Fig. 2When the endoscope arrives at the left pyriform sinus (arrow) as seen on the left side of the screen, its tip is maneuvered so that it faces the center and the endoscope is carefully inserted.

|

Go to :

COMPLETE OBSERVATION

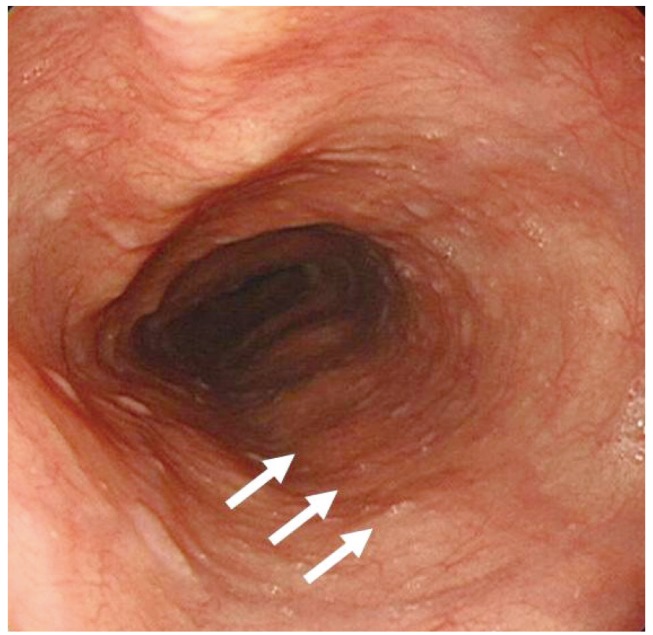

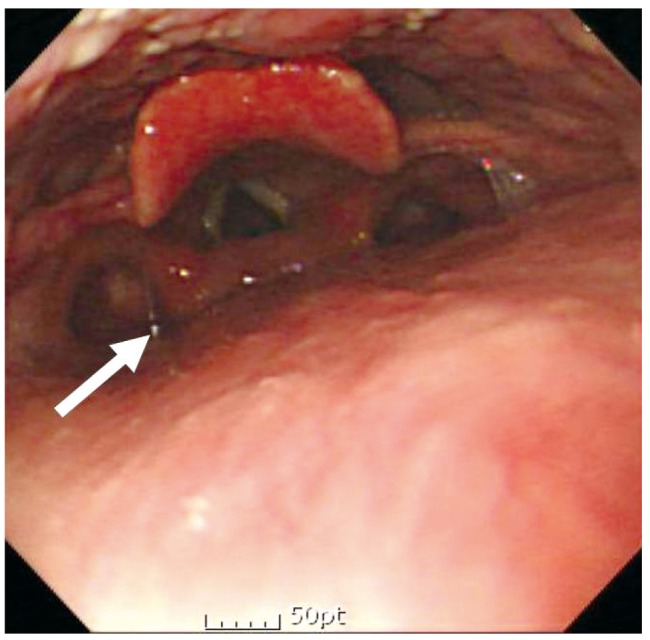

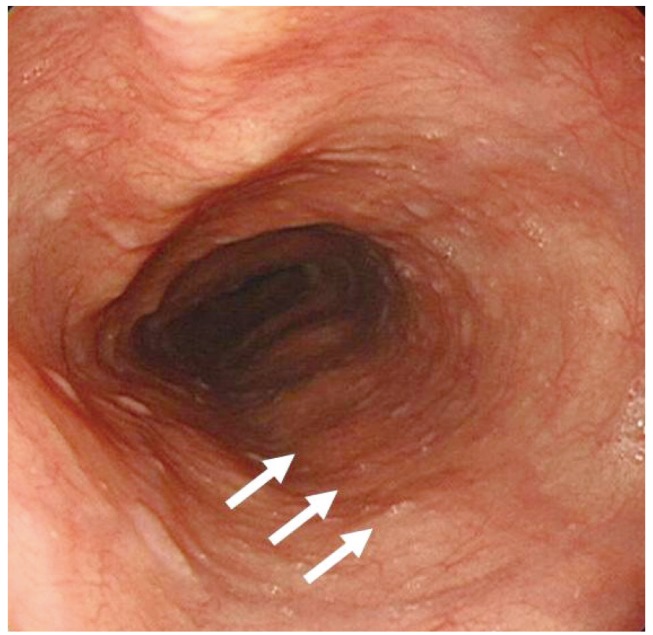

After the endoscope passes the upper esophageal sphincter and enters the esophagus, there should be no further difficulty in its movement. Apart from the upper and lower esophageal sphincters in the esophagus, pressure from the aortic arch (23 to 25 cm from the incisors in adults) and the left bronchus (27 to 29 cm from the incisors) can form physiological strictures. Compression from the spine or left atrium (32 to 34 cm from the incisors) can be observed in healthy subjects, so care must be taken not to mistake these for pathological lesions (

Fig. 3).

| Fig. 3Compression from the spine (arrows). Care must be taken not to mistake these for pathological lesions.

|

While the insertion tube passes through the lower esophagus at 40 to 42 cm from the incisors, the gastroesophageal junction can be observed. Precise observation of this area is very important in the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

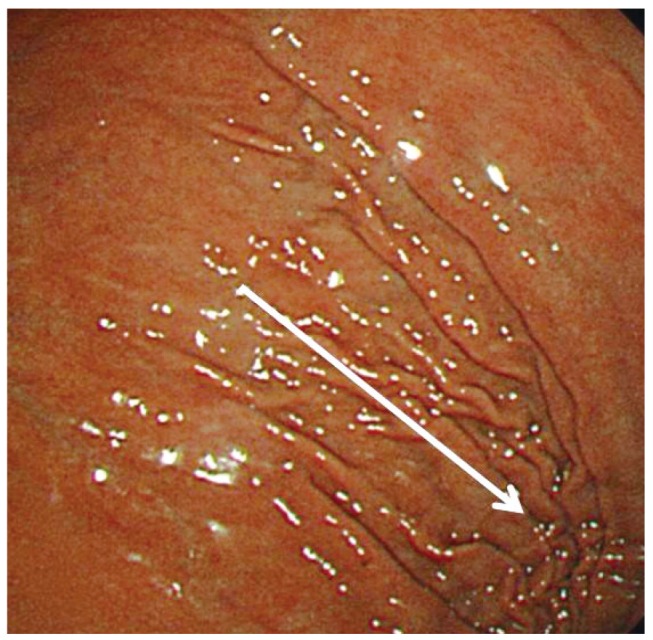

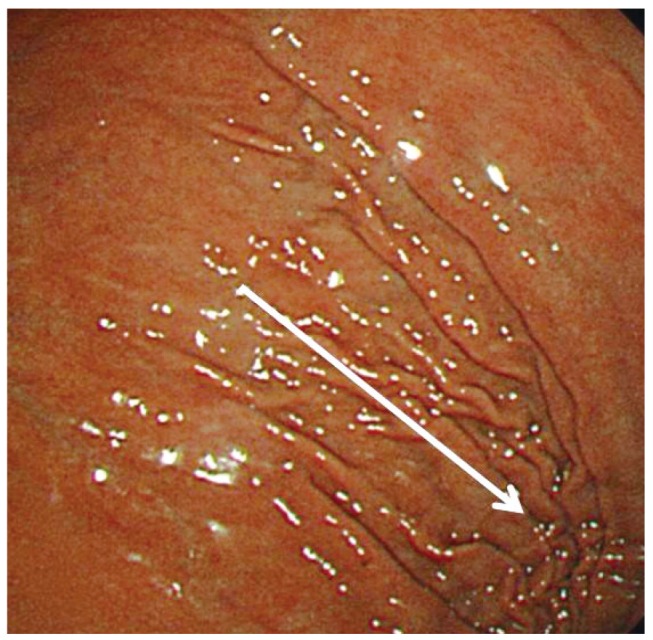

As the tube enters the stomach, gastric folds can be observed in the 10 and 4 o'clock positions (

Fig. 4). It is possible to proceed easily to the antrum if the operator naturally rotates the endoscope by turning their body and arm clockwise while infusing air to adjust their position so that the gastric folds flow in the 6 and 12 o'clock directions. If the path forward does not appear, even when the process is repeated, a malfunctioning air infusion system, Borrmann type 4 gastric cancer, or situs inversus should be excluded.

| Fig. 4As the tube enters the stomach, gastric folds can be observed in the 10 and 4 o'clock positions.

|

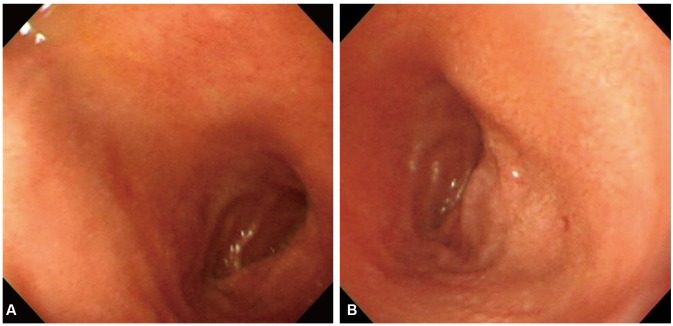

Although the order of observations may differ depending on the operator, it is important to consistently and precisely observe all regions without missing any points. Many endoscopists, including myself, first observe the duodenum and then precisely observe the stomach while withdrawing the endoscope. As soon as the endoscope passes through the pylorus, the duodenal bulb is observed, with the anterior wall and the lesser curvature observed simultaneously in the 8 and 11 o'clock positions, respectively. As the left arm is rotated clockwise, the posterior wall and greater curvature are observed simultaneously in the 2 and 5 o'clock positions (

Fig. 5). The rotation of the left arm in a clockwise direction rotates the endoscope toward the posterior wall to enable easier observation of the posterior wall in both the stomach and the duodenum. The passage connecting to the second portion of the duodenum is located in the 3 to 4 o'clock position, and the second portion of the duodenum can be entered by placement of the tip of the endoscope in this part, upward deflection while pushing gently, and turning the left arm clockwise. In the second portion of the duodenum, after observation of the ampulla, which usually appears at the 9 o'clock position, the endoscope is removed through reversal of the insertion process, which allows re-visualization of the duodenum.

| Fig. 5Duodenal bulb. (A) The anterior wall and the lesser curvature can be observed simultaneously in the 8 and 11 o'clock positions, respectively. (B) As the left arm is rotated clockwise, the posterior wall and greater curvature are observed simultaneously in the 2 and 5 o'clock positions.

|

After the endoscope is removed from the duodenum, the anterior wall and lesser curvature of the antrum as well as the posterior wall and greater curvature are observed in detail. Then if the endoscope is deflected up at the appropriate position (called a "J-turn"), the gastric angle can be observable at the front of the field of view. From this position, the anterior and posterior walls of the gastric angle are observed by rotating the left arm in a clockwise or counterclockwise direction. If the endoscope is pulled back gradually, maintaining it in the J-turn position, the lesser curvature of the lower, middle, and upper body can be observed; in contrast, rotation of the left arm in the clockwise direction while the J-turn position is maintained is called the "U-turn," which enables observation of the fundus. After this, as the left arm is rotated to the appropriate extent in both directions and the endoscope is pushed as far as the gastric angle, the body of the stomach is observed. After the J-turn is released in the gastric angle, with the endoscope straightened, it is pulled back and the lower, middle, and upper parts of the body can be observed in detail. Usually, the anterior wall and lesser curvature are observed simultaneously and the endoscope is rotated posteriorly by clockwise rotation of left arm for simultaneous observation of the posterior wall and greater curvature.

When it is judged that every part of the stomach has been observed and nothing has been missed, the upper and lower esophagus should be observed one more time in detail as the endoscope is removed; at this time, if allowed by the apparatus, image enhanced-endoscopy such as flexible spectral imaging color enhancement or narrow band imaging can be used.

Go to :

APPROPRIATE PHOTOGRAPHING

In the past, there were major restrictions on the number of endoscopy images that could be printed due to the high cost and scarcity of space; as such, records mostly focused on lesions. However, since images can now be stored on computers at most endoscopy centers, the storage of high-resolution images of several areas is recommended whenever possible; in particular, even if there are no special lesions, storage of images of all major areas to show negative results is recommended.

Tips for taking high-quality images

First, foreign materials on the endoscope lens prohibit precise observation and high-resolution imaging, so the lens and endoscope screen must be checked before insertion and any foreign materials must be removed.

When there is considerable movement of the target area due to the patient's gut movements or heavy breathing, the operator should wait a few seconds before obtaining images. It is best to position the lesion or area of interest in the middle of the screen and make adjustments so that the lesion is neither too bright nor too dark. Prior to capturing close-up images of the lesion, it is good to select a composition that shows not only the entire lesion on one screen but also its relationship with the surrounding background. After taking a wide image from a distance, the operator should gradually approach the lesion to take a close-up image. If the lesion is too large to fit within a single screen, it should be divided and imaged consecutively so that its overall shape can be deduced. Furthermore, the lesion should be imaged from several angles; in particular, its characteristic appearance should be imaged since this is of diagnostic value.

When performing lesion observations and imaging, it is important to infuse the appropriate amount of air and take the photograph with the surrounding folds suitably spread. To gauge lesion size, it is best to take an image with open biopsy forceps. For lesion sites that are soft or can be pressed, taking a photograph while the lesion is being pressed with the biopsy forceps indirectly conveys its characteristics. Several methods can be used to record the precise location of small lesions, including marking the position on the monitor during the endoscopy procedure, using the biopsy forceps or an endoscope ruler to indicate the lesion, and obtaining an image of the biopsy location when bleeding occurs immediately after the biopsy.

In some cases, the use of chromoendoscopy can be helpful. Indigo carmine helps visualize minute depressions by a contrast method, while Lugol's solution helps to confirm suspected esophageal dysplasia or esophageal cancer lesions and to determine their extent. Recently, methods such as narrow band endoscopy, which uses a light source of a particular wavelength, are frequently used instead of chromoendoscopy.

Essential photographing sites

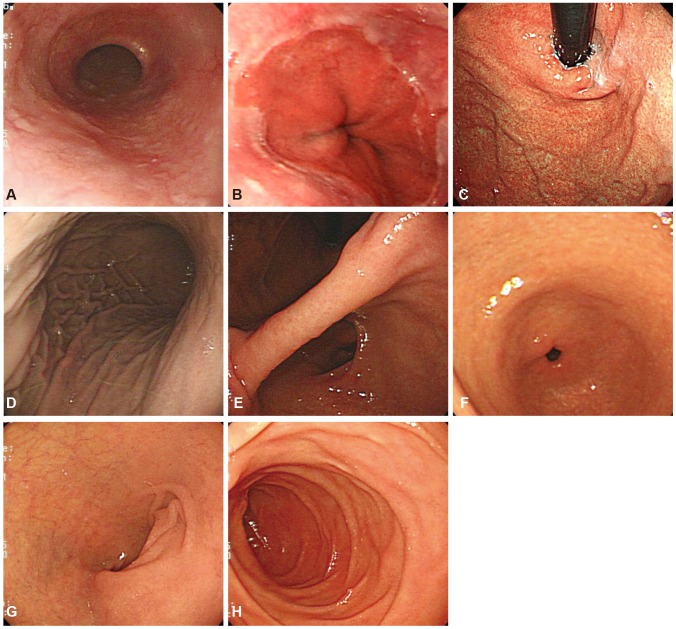

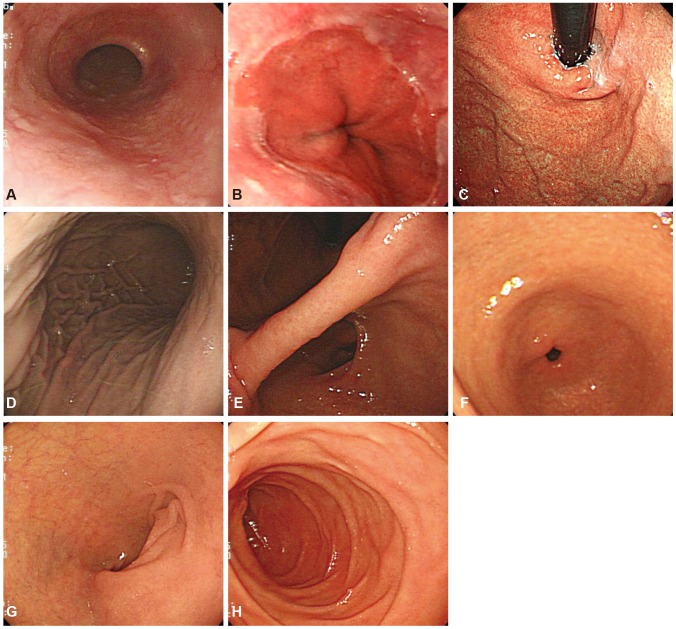

Although the photographing order can differ among examiners, it is very important that images of the following sites are consistently collected (

Fig. 6):

11 (1) upper esophagus, 20 cm from the incisors; (2) lower esophagus, 2 cm superior to the gastroesophageal junction (this site is important when checking for Barrett's esophagus or reflux esophagitis); (3) cardia and fundus in the U-turn position; (4) lesser curvature of the upper body (this image should be taken after sufficient expansion of the fundus); (5) gastric angle in the J-turn position; (6) entire gastric antrum; (7) entire duodenal bulb; and (8) second portion of the duodenum. The tip of the endoscope should be positioned at the ampulla.

| Fig. 6Essential photographing sites. (A) Upper esophagus. (B) Lower esophagus. (C) Gastric cardia and fundus. (D) Upper body. (E) Gastric angle. (F) Gastric antrum. (G) Duodenal bulb. (H) Duodenal second portion.

|

Considering the situation in Korea where various gastric diseases are common, the European guideline that recommends obtaining only four gastric images may not be applicable in Korea. Further investigation and studies to establish a consensus on this are warranted.

Go to :

CONCLUSIONS

In this review, factors that novice endoscopists performing upper GI endoscopy must be aware of are discussed, including proper endoscope insertion, precise observation without blind spots, and appropriate photographing. There is a definite need for qualitative improvements in endoscopy to meet the quantitative increase in the performance of the procedure. If only to counteract the gradually increasing number of medical lawsuits, high-quality endoscopy that considers these factors must be performed. Knowledge and practice of the above points may form the basis of qualitative improvements in endoscopy, which are currently being emphasized.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download