Abstract

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) is an ingestible video camera that transmits high-quality images of the small intestinal mucosa. This makes the small intestine more readily accessible to physicians investigating the presence of small bowel disorders, such as Crohn's disease (CD). Although VCE is frequently performed in Korea, there are no evidence-based guidelines on the appropriate use of VCE in the diagnosis of CD. To provide accurate information and suggest correct testing approaches for small bowel diseases, the Korean Gut Image Study Group, part of the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, developed guidelines on VCE. Teams were set up to develop guidelines on VCE. Four areas were selected: diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, small bowel preparation for VCE, diagnosis of CD, and diagnosis of small bowel tumors. Three key questions were selected regarding the role of VCE in CD. In preparing these guidelines, a systematic literature search, evaluation, selection, and meta-analysis were performed. After writing a draft of the guidelines, the opinions of various experts were solicited before producing the final document. These guidelines are expected to play a role in the diagnosis of CD. They will need to be updated as new data and evidence become available.

Video capsule endoscopy (VCE) allows physicians to readily access the small intestine to investigate suspected small bowel disorders, such as Crohn's disease (CD). VCE was introduced at the outset of the 21st century. During the past decade, numerous studies have confirmed that VCE is a noninvasive and highly reliable diagnostic tool for examining mucosa in the small intestine. CD is a chronic inflammatory disease that can involve the entire gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. According to Western population-based epidemiological studies, small bowel involvement occurs in over 50% of CD patients.1,2,3,4,5 However, it is not possible to directly observe deep small bowel mucosa with radiological evaluations, such as small bowel follow-through (SBFT), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Such evaluations can also miss subtle mucosal lesions in the small intestine. Even with wired small bowel endoscopies, such as push enteroscopy (PE), Sonde enteroscopy, and balloon-assisted enteroscopy, it is difficult to evaluate the entire small bowel. Moreover, the aforementioned procedures are very invasive. Therefore, there could be a role for VCE in the evaluation of small bowel mucosa in cases of suspected and established CD. Previous meta-analyses of Western populations demonstrated that VCE has a higher diagnostic yield in suspected and established CD patients than alternative modalities.6,7 To help establish the role of VCE and other diagnostic techniques in the management of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), literature reviews and guidelines have been published, primarily in Western countries.6,7 Evidence-based guidelines on the use of VCE that are suited to the circumstances of each country are mandatory. Moreover, the incidence and prevalence of IBD, especially CD, are rapidly increasing in Korea, and about 90% of Korean CD patients have small bowel involvement.8 Thus, appropriate guidelines on the use of VCE in CD are needed. Such guidelines are expected to enhance the efficient utilization of limited medical resources in Korea, to propose adequate diagnostic approaches for patients with suspected or established CD, and to substantially reduce the socioeconomic burden caused by excessive medical testing.

The guidelines were developed by systematically reviewing the literature published in Korea and abroad and by compiling the opinions of VCE experts in Korea on three key questions regarding the role of VCE in suspected and established CD. The objective of these guidelines is to provide accurate information and to suggest correct testing approaches to medical professionals caring for patients with suspected or established CD.

A multisociety VCE guideline operation committee and a working committee were formed in April 2010 consisting of experts and clinical treatment guideline professionals from the Korean Society of Gastroenterology, the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases. Four operation teams were organized to develop VCE guidelines on the following subjects: diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, small bowel preparation for VCE, diagnosis of CD, and diagnosis of small bowel tumors. There was no conflict of interest among the participants in the development process of the guidelines.

A working committee was established to select three key questions regarded as pivotal to medical professionals concerning the role of VCE for CD. The patient/population-intervention-comparison-outcome rule was applied to develop the key questions. The three key questions were as follows. (1) Does VCE have a higher diagnostic yield than other diagnostic modalities in patients with suspected or established CD? (2) Are small bowel radiological examinations or patency capsule (PC) examinations required for evaluating patients with suspected or established CD before VCE? (3) Is the addition of VCE after negative ileocolonoscopy and small bowel radiological examinations effective in patients with a high probability of CD?

For the first key question, we performed online searches for VCE-related clinical studies, comparative research, randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and guidelines published between January 2000 and September 2010. The foreign literature searches used MEDLINE and the Cochrane library. The Korean literature searches used the Korean Medical Database, the Korean Studies Information Service System, and KoreaMed. The searches initially produced 3,271 VCE-related article titles and abstracts. Of these, 449 full papers on VCE and CD were selected. We then carefully reviewed the selected articles and excluded studies of children and studies unrelated to the first key question. After the exclusion process, 89 articles were selected. In addition, one full paper and two abstracts were added after evaluating a previous meta-analysis.7 Ninety-two articles were finally selected.

For the second key question, we performed an online search process similar to that used for the first key question during the same period. The search terms used were "retention," "capsule endoscopy," and "patency capsule." This search yielded 10 documents on the retention rate of VCE (M2A; Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel)9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 and six prospective studies on the usefulness of the PC (M2A Patency Capsule; Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel).19,20,21,22,23,24

After reviewing the selected articles for the first key question, standardized evidence tables were created to extract information pertinent to the first key question. After creating evidence tables for the first key question, we conducted meta-an-alyses of the search results containing comparative studies of VCE and other diagnostic modalities. The meta-analyses were performed using Stata version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

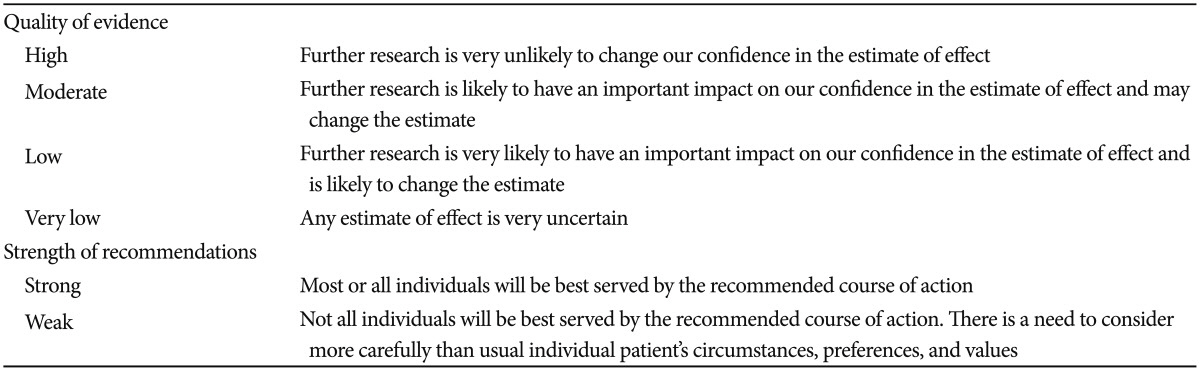

For the quality of evidence and the strength of recommendations, the methodology proposed by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GR-ADE) Working Group was used.30,31 The quality of evidence indicates the level of scientific evidence of the recommendation, and the strength of the recommendation indicates the grade of confidence that adherence to the recommendation will do more good than harm (Table 1).30,31

After writing drafts of the VCE guidelines on CD on the basis of the meta-analyses and review of the selected literature, we conducted an Internet survey to reflect the medical environment in Korea and assess the provision of VCE by medical professionals in actual clinical settings. Opinions from various professionals in Korea were obtained and compiled before having the draft recommendation approved. The final recommendations were based on a vote, with the grade of agreement as follows: (1) agree strongly; (2) agree with minor reservations; (3) agree with major reservations; (4) disagree with major reservations; (5) disagree with minor reservations; and (6) disagree strongly.

The published guidelines will be posted on the websites of the Korean Society of Gastroenterology, the Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, and the Korean Association for the Study of Intestinal Diseases. A summary of the guidelines, highlighting important recommendations, will be prepared and distributed to medical professionals free of charge.

VCE is the most sensitive diagnostic modality for detecting mucosal lesions in patients with suspected or established CD.

Evidence level: low; recommendation grade: strong.

Agreement: agree strongly (73.3%); agree with minor reservations (26.7%); agree with major reservations (0%); disagree with major reservations (0%); disagree with minor reservations (0%); disagree strongly (0%).

For evaluating small bowel mucosal lesions in patients with suspected or established CD, diverse diagnostic modalities are used, including ileocolonoscopy, PE, small bowel barium radiography, CT enterography (CTE)/CT enteroclysis (CTEC), MRI/ magnetic resonance enterography (MRE)/magnetic resonance enteroclysis (MREC), and VCE. VCE is expected to offer the potential to visualize the mucosa in the entire small bowel, which cannot be achieved by ileocolonoscopy and PE. In addition, it can be used to observe the small bowel mucosa directly, which allows superficial and small lesions to be detected, something that is difficult with traditional radiological modalities.

To answer the key question 1, we compared the diagnostic yield of VCE with that of ileocolonoscopy, PE, small bowel barium radiography, CTE/CTEC, and MRI/MRE/MREC. Among multiple studies using various types of VCE, only studies with capsule endoscopes produced by Given Imaging (M2A) were included in the analyses.

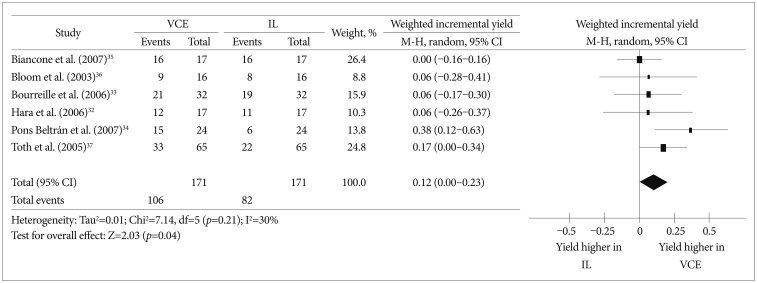

To date, four prospective studies32,33,34,35 and two abstracts36,37 have compared VCE and ileocolonoscopy in the evaluation of CD patients. We performed a meta-analysis using those six studies to compare the diagnostic yields of VCE and ileocolonoscopy in CD. The meta-analysis comparing the diagnostic yield in each study revealed that the weighted incremental yield of VCE compared to ileocolonoscopy was 0.12 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.00 to 0.23; p=0.04) (Fig. 1).

A disadvantage of PE in the evaluation of CD is that it cannot effectively shorten the bowel. Even with an overtube, the postpyloric insertion depth was reported to be up to 120 cm from the ligament of Treitz (permitting examination of only 60 to 120 cm from the ligament of Treitz).38,39 This shortcoming of PE could significantly limit the yield of PE when evaluating suspected or established CD patients. One prospective study40 and one abstract37 compared the effectiveness of VCE and PE in the diagnosis of small bowel CD patients. A meta-analysis using these two studies showed that the weighted incremental yield of VCE compared to PE was 0.43 (95% CI, 0.32 to 0.53; p<0.00001) (Fig. 2).

SBFT and small bowel barium enteroclysis are conventional methods for evaluating small bowel CD. Six prospective studies13,15,32,41,42,43 and two abstracts36,37 compared the effectiveness of VCE and small bowel barium radiography in the evaluation of small bowel CD patients. We performed a meta-analysis using these eight studies. The weighted incremental yield of VCE compared to small bowel barium radiography was 0.36 (95% CI, 0.26 to 0.46; p<0.00001) (Fig. 3).

Two prospective studies14,32 compared the effectiveness of VCE and CTE/CTEC in the evaluation of small bowel lesions in suspected or established CD patients. According to a meta-analysis of these two studies, the weighted incremental yield of VCE compared to CTE/CTEC was 0.28 (95% CI, 0.10 to 0.45; p=0.002) (Fig. 4).

MRI/MRE/MREC enables accurate diagnosis of intestinal and extraintestinal abdominal pathologies. Five prospective studies44,45,46,47,48 compared the effectiveness of VCE and MRE/MREC in the diagnosis of small bowel CD patients. A meta-analysis of these five studies revealed that the effectiveness of VCE and MRE/MREC was comparable. The weighted incremental yield of VCE compared to MRE/MREC was 0.08 (95% CI, -0.02 to 0.18; p=0.48) (Fig. 5).

In conclusion, VCE had a higher diagnostic yield than ileocolonoscopy, PE, small bowel barium radiography, and CTE/CTEC, but a similar diagnostic yield to MRE/MREC in suspected or established CD patients.

Small bowel radiological examinations or PC examinations are recommended before VCE for evaluating patients with suspected or established CD.

Evidence level: low; recommendation grade: strong.

Agreement: agree strongly (40%); agree with minor reservations (53.3%); agreewith major reservations (6.7%); disagree with major reservations (0%); disagree with minor reservations (0%); disagree strongly (0%).

Small bowel strictures, which are relatively common in CD patients, are considered a contraindication to VCE for fear of VCE retention. The outer dimensions of M2A are 26×11 mm, which can cause the capsule to become stuck in the narrower segments of the bowel. We analyzed 10 studies9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 that investigated the VCE retention rate in suspected or confirmed CD patients. In those studies, the VCE retention rate ranged from 0% to 13.2%. When the patient group was divided into suspected CD patients and confirmed CD patients, the retention rate in the suspected CD group was 0% to 5.4%9,10,11,16,17,18 and that in the confirmed CD group was 0% to 13.2%.13,14,15,16,17

In addition to traditional radiological examinations, the PC test can be used before VCE in suspected or confirmed small bowel CD patients to evaluate the stenosis of the small bowel and the possibility of VCE retention. The outer dimensions of the PillCam PC (Given Imaging) are the same (26×11 mm) as those of the M2A, and it is composed of lactose.19 It remains intact in the gastrointestinal tract for 40 to 100 hours postingestion and disintegrates thereafter.19 To date, six prospective observational studies19,20,21,22,23,24 on the role of PC evaluation in patients with suspected strictures, including CD, have been published. In all these studies, VCE passage was successful (100%), without retention after passage of the intact PC. In a retrospective study49 that compared the PC with radiological examinations to detect clinically significant small bowel strictures in 42 patients, 25 suspected or confirmed CD patients underwent PC evaluations as well as radiological examinations. The gold standard was small bowel obstruction/significant strictures at surgery or VCE retention in the small bowel.49 With regard to the performances of PC and radiological examinations, PC and radiology showed similar sensitivity (57% vs. 71%, p=1.00) and specificity (86% vs. 97%, p=0.22).49 When a positive result by either PC or radiological examination was considered positive, all seven cases of surgically confirmed small bowel obstruction could be correctly identified with 100% sensitivity and 100% negative predictive values.49

In conclusion, VCE retention is not an uncommon complication in CD patients, especially in those with established CD. Therefore, small bowel radiological examinations or PC examinations are recommended before VCE for evaluating suspected or established CD patients to rule out the possibility of small bowel strictures. A combination of both examinations appears to be useful to exclude the possibility of significant small bowel strictures. However, because PC evaluation is not yet available in many countries including Korea, adequate radiologic evaluation of the small bowel is needed before VCE in suspected or established CD patients.

In well-selected patients with a high suspicion of CD, VCE is useful for diagnosing CD after negative ileocolonoscopy and small bowel radiologic examination.

Evidence level: low; recommendation grade: weak.

Agreement: agree strongly (33.3%); agree with minor reservations (53.4%); agreewith major reservations (13.3%); disagree with major reservations (0%); disagree with minor reservations (0%); disagree strongly (0%).

Although VCE is a noninvasive tool for evaluating abnormal lesions by visualizing the entire small bowel, it is still an expensive diagnostic tool in many countries, including Korea. In addition, there is a substantial risk of VCE retention in CD patients. Furthermore, although a small bowel radiological examination or PC test is a useful tool for physicians to rule out significant small bowel strictures before VCE, PC evaluation is still not available in many countries, including Korea. Thus, in suspected CD patients with negative results in ileocolonoscopy and small bowel radiological examinations, the cost-effectiveness and risk-benefit ratio of a VCE examination should be carefully evaluated.

In a decision-analytic model evaluating 1-year costs, the cost of VCE for diagnostic evaluations of suspected CD was comparable to that of SBFT.25 In another study using a decision-analytic model, the authors compared the lifetime costs and benefits of each diagnostic strategy for diagnosing CD.26 They evaluated whether CTE is a cost-effective alternative to SBFT and whether VCE is a cost-effective third test in patients in whom a high suspicion of CD remains after two previous negative tests. They reported that the addition of VCE after ileocolonoscopy and a negative CTE or SBFT costs greater than US $500,000 per quality-adjusted life-years gained in all scenarios. Thus, they concluded that the addition of VCE as a third test is not cost-effective, even in patients with a high pretest probability of CD.26 However, decision-analytic models are based on multiple assumptions. Therefore, their results could not be extrapolated to clinical settings.

The impact of VCE on the diagnosis of CD in actual clinical settings is an important issue. In a study on pediatric patients, two of four (50%) ulcerative colitis/indeterminate colitis patients and eight of 10 (80%) suspected IBD patients could be reclassified as having small bowel CD by using VCE.27 Similarly, VCE ruled out IBD in 94% of the suspected IBD patients, and 50% of the presumed ulcerative colitis or unclassified IBD patients were reclassified as having CD.28 These two studies suggest a positive role of VCE in the correct diagnosis and classification of IBD.

There is no widely accepted consensus on the role of VCE in the diagnostic algorithm of CD, and no studies have directly compared VCE and enteroscopy for the diagnosis of CD. The second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of CD stated that VCE should be reserved for patients in whom the clinical suspicion of CD remains high, despite negative evaluations with ileocolonoscopy and radiological examinations (SBFT, CTE, or MRE).29

In conclusion, although evidence supporting the cost-effectiveness of VCE is lacking, it appears to have a role in the correct diagnosis of CD in a well-selected patient group with a high suspicion of CD.

(1) VCE is the most sensitive diagnostic modality for detecting mucosal lesions in patients with suspected or established CD (evidence level: low; recommendation grade: strong).

(2) Small bowel radiological examinations or PC examinations are recommended before VCE for evaluating patients with suspected or established CD (evidence level: low; recommendation grade: strong).

(3) In well-selected patients with a high suspicion of CD, VCE is useful for diagnosing CD after negative ileocolonoscopy and small bowel radiologic examination (evidence level: low; recommendation grade: weak).

Medical circumstances differ considerably between countries. Therefore, the availability of certain diagnostic tools and costs varies according to the area. For example, if PC evaluation is not available in certain countries such as Korea, cost-effective radiologic evaluation is needed to detect small bowel strictures before VCE in suspected or established CD patients. Further studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of various diagnostic tools are needed to examine the role of VCE in the diagnosis of CD, while considering the health care system and costs specific to each country.

References

1. Vind I, Riis L, Jess T, et al. Increasing incidences of inflammatory bowel disease and decreasing surgery rates in Copenhagen City and County, 2003-2005: a population-based study from the Danish Crohn colitis database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006; 101:1274–1282. PMID: 16771949.

2. Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Høie O, et al. Clinical course in Crohn's disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 5:1430–1438. PMID: 18054751.

3. Gower-Rousseau C, Vasseur F, Fumery M, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel diseases: new insights from a French population-based registry (EPIMAD). Dig Liver Dis. 2013; 45:89–94. PMID: 23107487.

4. Nuij VJ, Zelinkova Z, Rijk MC, et al. Phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease at diagnosis in the Netherlands: a population-based inception cohort study (the Delta Cohort). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:2215–2222. PMID: 23835444.

5. Sjöberg D, Holmström T, Larsson M, et al. Incidence and clinical course of Crohn's disease during the first year: results from the IBD Cohort of the Uppsala Region (ICURE) of Sweden 2005-2009. J Crohns Colitis. 2014; 8:215–222. PMID: 24035547.

6. Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Bianco MA, Cipolletta L. Meta-analysis: capsule enteroscopy vs. conventional modalities in diagnosis of small bowel diseases. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005; 22:595–604. PMID: 16181299.

7. Dionisio PM, Gurudu SR, Leighton JA, et al. Capsule endoscopy has a significantly higher diagnostic yield in patients with suspected and established small-bowel Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:1240–1248. PMID: 20029412.

8. Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008; 14:542–549. PMID: 17941073.

9. Herrerías JM, Caunedo A, Rodríguez-Téllez M, Pellicer F, Herrerías JM Jr. Capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected Crohn's disease and negative endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2003; 35:564–568. PMID: 12822090.

10. Fireman Z, Mahajna E, Broide E, et al. Diagnosing small bowel Crohn's disease with wireless capsule endoscopy. Gut. 2003; 52:390–392. PMID: 12584221.

11. Eliakim R, Fischer D, Suissa A, et al. Wireless capsule video endoscopy is a superior diagnostic tool in comparison to barium follow-through and computerized tomography in patients with suspected Crohn's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003; 15:363–367. PMID: 12655255.

12. Mow WS, Lo SK, Targan SR, et al. Initial experience with wireless capsule enteroscopy in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004; 2:31–40. PMID: 15017630.

13. Buchman AL, Miller FH, Wallin A, Chowdhry AA, Ahn C. Video capsule endoscopy versus barium contrast studies for the diagnosis of Crohn's disease recurrence involving the small intestine. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004; 99:2171–2177. PMID: 15554999.

14. Voderholzer WA, Beinhoelzl J, Rogalla P, et al. Small bowel involvement in Crohn's disease: a prospective comparison of wireless capsule endoscopy and computed tomography enteroclysis. Gut. 2005; 54:369–373. PMID: 15710985.

15. Marmo R, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, et al. Capsule endoscopy versus enteroclysis in the detection of small-bowel involvement in Crohn's disease: a prospective trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005; 3:772–776. PMID: 16234005.

16. Cheifetz AS, Kornbluth AA, Legnani P, et al. The risk of retention of the capsule endoscope in patients with known or suspected Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006; 101:2218–2222. PMID: 16848804.

17. Cheon JH, Kim YS, Lee IS, et al. Can we predict spontaneous capsule passage after retention? A nationwide study to evaluate the incidence and clinical outcomes of capsule retention. Endoscopy. 2007; 39:1046–1052. PMID: 18072054.

18. Petruzziello C, Calabrese E, Onali S, et al. Small bowel capsule endoscopy vs conventional techniques in patients with symptoms highly compatible with Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2011; 5:139–147. PMID: 21453883.

19. Spada C, Spera G, Riccioni M, et al. A novel diagnostic tool for detecting functional patency of the small bowel: the Given patency capsule. Endoscopy. 2005; 37:793–800. PMID: 16116528.

20. Boivin ML, Lochs H, Voderholzer WA. Does passage of a patency capsule indicate small-bowel patency? A prospective clinical trial? Endoscopy. 2005; 37:808–815. PMID: 16116530.

21. Signorelli C, Rondonotti E, Villa F, et al. Use of the given patency system for the screening of patients at high risk for capsule retention. Dig Liver Dis. 2006; 38:326–330. PMID: 16527556.

22. Spada C, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, et al. Video capsule endoscopy in patients with known or suspected small bowel stricture previously tested with the dissolving patency capsule. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007; 41:576–582. PMID: 17577114.

23. Banerjee R, Bhargav P, Reddy P, et al. Safety and efficacy of the M2A patency capsule for diagnosis of critical intestinal patency: results of a prospective clinical trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 22:2060–2063. PMID: 17614957.

24. Herrerias JM, Leighton JA, Costamagna G, et al. Agile patency system eliminates risk of capsule retention in patients with known intestinal strictures who undergo capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:902–909. PMID: 18355824.

25. Leighton JA, Gralnek IM, Richner RE, Lacey MJ, Papatheofanis FJ. Capsule endoscopy in suspected small bowel Crohn's disease: economic impact of disease diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2009; 15:5685–5692. PMID: 19960565.

26. Levesque BG, Cipriano LE, Chang SL, Lee KK, Owens DK, Garber AM. Cost effectiveness of alternative imaging strategies for the diagnosis of small-bowel Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 8:261–267. PMID: 19896559.

27. Gralnek IM, Cohen SA, Ephrath H, et al. Small bowel capsule endoscopy impacts diagnosis and management of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective study. Dig Dis Sci. 2012; 57:465–471. PMID: 21901253.

28. Min SB, Le-Carlson M, Singh N, et al. Video capsule endoscopy impacts decision making in pediatric IBD: a single tertiary care center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013; 19:2139–2145. PMID: 23867872.

29. Van Assche G, Dignass A, Panes J, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2010; 4:7–27. PMID: 21122488.

30. Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004; 328:1490. PMID: 15205295.

31. Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008; 336:924–926. PMID: 18436948.

32. Hara AK, Leighton JA, Heigh RI, et al. Crohn disease of the small bowel: preliminary comparison among CT enterography, capsule endoscopy, small-bowel follow-through, and ileoscopy. Radiology. 2006; 238:128–134. PMID: 16373764.

33. Bourreille A, Jarry M, D'Halluin PN, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy versus ileocolonoscopy for the diagnosis of postoperative recurrence of Crohn's disease: a prospective study. Gut. 2006; 55:978–983. PMID: 16401689.

34. Pons Beltrán V, Nos P, Bastida G, et al. Evaluation of postsurgical recurrence in Crohn's disease: a new indication for capsule endoscopy? Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 66:533–540. PMID: 17725942.

35. Biancone L, Calabrese E, Petruzziello C, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy and small intestine contrast ultrasonography in recurrence of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007; 13:1256–1265. PMID: 17577246.

36. Bloom PD, Rosenberg MD, Klein SD, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy (CE) is more informative than ileoscopy and SBFT for the evaluation of the small intestine (SI) in patients with known or suspected Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003; 124(4 Suppl 1):A203–A204.

37. Toth E, Almqvist P, Benoni C. Endoscopic diagnosis of small bowel Crohn's disease: a prospective, comparative study of capsule endoscopy, barium enterography, push enteroscopy and ileo-colonoscopy. Gut. 2005; 54:A50.

38. Taylor AC, Chen RY, Desmond PV. Use of an overtube for enteroscopy: does it increase depth of insertion? A prospective study of enteroscopy with and without an overtube. Endoscopy. 2001; 33:227–230. PMID: 11293754.

39. Benz C, Jakobs R, Riemann JF. Do we need the overtube for push-enteroscopy? Endoscopy. 2001; 33:658–661. PMID: 11490380.

40. Chong AK, Taylor A, Miller A, Hennessy O, Connell W, Desmond P. Capsule endoscopy vs. push enteroscopy and enteroclysis in suspected small-bowel Crohn's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 61:255–261. PMID: 15729235.

41. Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, et al. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002; 123:999–1005. PMID: 12360460.

42. Dubcenco E, Jeejeebhoy KN, Petroniene R, et al. Capsule endoscopy findings in patients with established and suspected small-bowel Crohn's disease: correlation with radiologic, endoscopic, and histologic findings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 62:538–544. PMID: 16185968.

43. Efthymiou A, Viazis N, Vlachogiannakos J, et al. Wireless capsule endoscopy versus enteroclysis in the diagnosis of small-bowel Crohn's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 21:866–871. PMID: 19417679.

44. Albert JG, Martiny F, Krummenerl A, et al. Diagnosis of small bowel Crohn's disease: a prospective comparison of capsule endoscopy with magnetic resonance imaging and fluoroscopic enteroclysis. Gut. 2005; 54:1721–1727. PMID: 16020490.

45. Gölder SK, Schreyer AG, Endlicher E, et al. Comparison of capsule endoscopy and magnetic resonance (MR) enteroclysis in suspected small bowel disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006; 21:97–104. PMID: 15846497.

46. Tillack C, Seiderer J, Brand S, et al. Correlation of magnetic resonance enteroclysis (MRE) and wireless capsule endoscopy (CE) in the diagnosis of small bowel lesions in Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008; 14:1219–1228. PMID: 18484672.

47. Crook DW, Knuesel PR, Froehlich JM, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance enterography and video capsule endoscopy in evaluating small bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 21:54–65. PMID: 19086147.

48. Bocker U, Dinter D, Litterer C, et al. Comparison of magnetic resonance imaging and video capsule enteroscopy in diagnosing small-bowel pathology: localization-dependent diagnostic yield. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010; 45:490–500. PMID: 20132082.

49. Yadav A, Heigh RI, Hara AK, et al. Performance of the patency capsule compared with nonenteroclysis radiologic examinations in patients with known or suspected intestinal strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 74:834–839. PMID: 21839995.

Fig. 1

Comparison of the diagnostic yields between video capsule endoscopy and ileocolonoscopy in Crohn's disease patients. VCE, video capsule endoscopy; IL, ileocolonoscopy; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 2

Comparison of the diagnostic yields between video capsule endoscopy and push enteroscopy (PE) in Crohn's disease patients. VCE, video capsule endoscopy; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 3

Comparison of the diagnostic yields between video capsule endoscopy and small bowel barium radiography in Crohn's disease patients. VCE, video capsule endoscopy; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 4

Comparison of the diagnostic yields between video capsule endoscopy and computed tomography enterography/computed tomography enteroclysis in Crohn's disease patients. VCE, video capsule endoscopy; CTE, computed tomography enterography; CTEC, computed tomography enteroclysis; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 5

Comparison of the diagnostic yields between video capsule endoscopy and magnetic resonance enterography/magnetic resonance enteroclysis in Crohn's disease patients. VCE, video capsule endoscopy; MRE, magnetic resonance enterography; MREC, magnetic resonance enteroclysis; CI, confidence interval.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download