Abstract

Duodenal stenosis and duodenal atresia are well-known gastrointestinal anomalies in patients with Down syndrome. Although duodenal atresia presents early and classically with vomiting in the immediate neonatal period, the presentation of duodenal stenosis can be significantly more subtle and the diagnosis delayed. Here, we describe the case of a 5-month-old male infant with Down syndrome and delayed presentation of high-grade duodenal stenosis diagnosed endoscopically. Pediatric gastroenterologists should include duodenal stenosis in the differential diagnosis of older infants and children with vomiting and should be familiar with the endoscopic appearance of this lesion.

Duodenal atresia and stenosis are rare causes of intestinal obstruction in the newborn, with a prevalence of 1 in 5,000 to 10,000 live births, with duodenal stenosis occurring less frequently than duodenal atresia.1 However, these intestinal tract anomalies occur significantly more frequently in patients with Down syndrome. Approximately 2.5% of infants with Down syndrome are ultimately diagnosed with either duodenal atresia or stenosis.2 Conversely, 24% of patients with duodenal atresia or stenosis carry a diagnosis of Down syndrome.3

Duodenal atresia invariably presents within the first few hours to days of life with persistent vomiting after all feeds. In general, the atresia occurs at the level of, or just distal to, the ampulla of Vater.4 As a consequence, the emesis is frequently bilious and quickly brought to the attention of the medical provider. On the other hand, duodenal stenosis is incomplete duodenal obstruction and therefore presents significantly more subtly. Recurrent episodes of vomiting and failure to thrive are the most common presenting symptoms of duodenal stenosis.5

We report this case because of its unusual and delayed presentation despite the presence of high-grade stenosis. Moreover, few endoscopic images of duodenal stenosis have been published in the literature, suggesting that this finding is uncommon, but providers need to be prepared to encounter this complication.

A 5-month-old male infant with Down syndrome presented to the emergency department with coffee-ground emesis. Two weeks before admission, the patient had a single episode of emesis with dark streaks concerning for blood. He looked well on examination by his pediatrician and was started on lansoprazole with the plan to follow-up at our pediatric gastroenterology clinic. However, coffee-ground emesis recurred, and the infant was referred to the emergency department for evaluation. He had been exclusively breastfed and had fed well without emesis until this time. Growth had been appropriate for a child with Down syndrome. At the time of the emergency room evaluation, the infant looked well and had normal abdominal examination results. The emesis tested positive for occult blood. Laboratory data including a complete blood count and coagulation studies were normal. Abdominal radiography showed a normal bowel gas pattern.

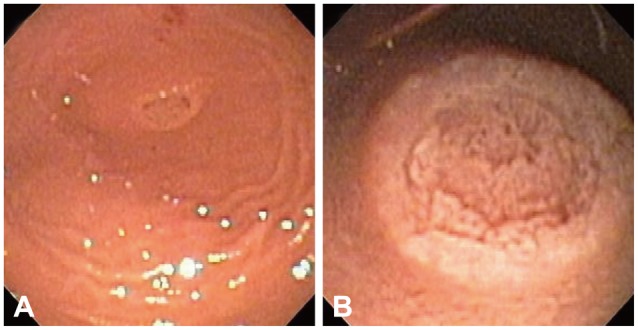

On the day of admission, the patient underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy using a GIF-XP 160 endoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). There was mild erythema in the distal esophagus, and a dark brown substance was observed in the stomach, consistent with blood exposed to gastric secretions. The duodenal bulb ended blindly (Fig. 1A), with a tubular structure containing normal-appearing villous mucosa in the center (Fig. 1B). No lumen could be identified in this structure.

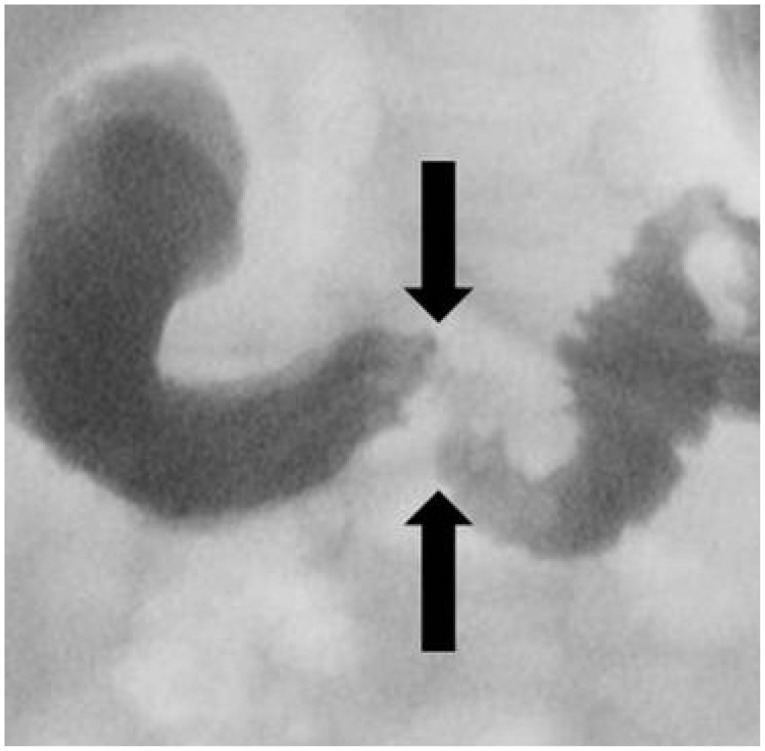

An upper gastrointestinal series (Fig. 2) demonstrated a markedly dilated duodenal bulb and narrowing of the second portion of the duodenum (arrows), confirming the suspicion of duodenal stenosis. The infant was treated with a diamond-shaped duodenoduodenostomy. Intestinal malrotation was also identified at the time of surgery; and therefore, the patient underwent Ladd's procedure. He recovered uneventfully and had an uncomplicated postoperative course.

Duodenal stenosis frequently presents with recurrent vomiting and failure to thrive. Owing to its chronic and variable presentation, the diagnosis is often delayed. It has been reported that the presentation and diagnosis of duodenal stenosis may be delayed to as late as adolescence.6 Therefore, pediatric providers should maintain a high index of suspicion for duodenal stenosis, particularly in patients with Down syndrome.

Our patient presented at the age of 5 months, outside of the immediate neonatal period, and with the atypical presenting sign of hematemesis. However, other studies have reported that hematemesis is the primary presenting symptom of duodenal stenosis and atresia in children.7,8 The etiology of hematemesis in these patients is not clear but may be related to esophageal or gastric irritation in the setting of gastric stasis, recurrent reflux, and vomiting. Hematemesis has been better described in pyloric stenosis and is secondary to reflux esophagitis in these patients.9 The mechanism of duodenal stenosis may be similar. Our patient showed erythema in the distal esophagus and had no evidence of duodenitis; therefore, esophagitis was considered to be the most likely cause of bleeding.

A typical finding of duodenal atresia on abdominal radiography in infants is the "double bubble" sign, which is marked gaseous distention of the proximal duodenum and stomach. This finding is not uniformly reported in infants with duodenal stenosis. Duodenal stenosis is classically diagnosed by an upper gastrointestinal series, which demonstrates a dilated stomach and duodenal bulb and a narrowing in the duodenum at the location of stenosis.4 An upper gastrointestinal series was not used as the initial diagnostic modality in our patient because he reported hematemesis without a history of chronic vomiting as the primary presenting sign. Diagnosis by endoscopy is unusual, and few endoscopic images of congenital duodenal stenosis have been published in the literature so far.

Preoperative treatment of duodenal stenosis involves the correction of hypovolemia and electrolyte derangements. Once medically stable, the patients can undergo operative repair with duodenoduodenostomy performed with either side-to-side or diamond-shaped anastomosis. Our patient underwent a diamond-shaped duodenoduodenostomy, which allows earlier postoperative feeding and a shorter hospital stay and is therefore the preferred procedure.10

In conclusion, patients with Down syndrome are at a higher risk of gastrointestinal anomalies. Even high-grade duodenal stenosis can present late and atypically in children, as observed in our patient with hematemesis at 5 months of age. Therefore, pediatric gastroenterologists should maintain a high index of suspicion for congenital duodenal stenosis in older infants and children and should be familiar with the endoscopic appearance of this lesion.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health Award K23DK094832 to MJR and the Thrasher Research Fund Early Career Award to MRN.

References

1. Escobar MA, Ladd AP, Grosfeld JL, et al. Duodenal atresia and stenosis: long-term follow-up over 30 years. J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 39:867–871. PMID: 15185215.

2. Fabia J, Drolette M. Malformations and leukemia in children with Down's syndrome. Pediatrics. 1970; 45:60–70. PMID: 4243491.

3. Dalla Vecchia LK, Grosfeld JL, West KW, Rescorla FJ, Scherer LR, Engum SA. Intestinal atresia and stenosis: a 25-year experience with 277 cases. Arch Surg. 1998; 133:490–496. PMID: 9605910.

4. Vinocur DN, Lee EY, Eisenberg RL. Neonatal intestinal obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012; 198:W1–W10. PMID: 22194504.

5. Grosfeld JL, Rescorla FJ. Duodenal atresia and stenosis: reassessment of treatment and outcome based on antenatal diagnosis, pathologic variance, and long-term follow-up. World J Surg. 1993; 17:301–309. PMID: 8337875.

6. Savino A, Rollo V, Chiarelli F. Congenital duodenal stenosis and annular pancreas: a delayed diagnosis in an adolescent patient with Down syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2007; 166:379–380. PMID: 17043846.

7. Chhabra R, Suresh BR, Weinberg G, Marion R, Brion LP. Duodenal atresia presenting as hematemesis in a premature infant with Down syndrome. Case report and review of the literature. J Perinatol. 1992; 12:25–27. PMID: 1532826.

8. Sachs BF, Feldman W. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with congenital duodenal stenosis and Down's syndrome. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1973; 12:21A passim.

9. Takeuchi S, Tamate S, Nakahira M, Kadowaki H. Esophagitis in infants with hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: a source of hematemesis. J Pediatr Surg. 1993; 28:59–62. PMID: 8429475.

10. Kimura K, Mukohara N, Nishijima E, Muraji T, Tsugawa C, Matsumoto Y. Diamond-shaped anastomosis for duodenal atresia: an experience with 44 patients over 15 years. J Pediatr Surg. 1990; 25:977–979. PMID: 2213450.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download