Abstract

Tuberculosis remains a serious infectious disease with primary features of pulmonary manifestation in Korea. However, duodenal tuberculosis is rare in gastrointestinal cases of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Here, we report a case of primary duodenal tuberculosis mistaken as a malignant tumor and diagnosed with QuantiFERON-TB GOLD (Cellestis Ltd.) in an immunocompetent male patient.

The prevalence of tuberculosis has rapidly declined in the past years. However, the proportion of extrapulmonary tuberculosis has been increasing in Korea.1 Gastrointestinal tuberculosis is not a common disease, and it is difficult to diagnose because of its vague symptoms. Moreover, primary duodenal tuberculosis is rare, and only a few cases have been reported.2,3 We report a case of primary duodenal tuberculosis confused with a malignant tumor in a 24-year-old immunocompetent male patient without any features of pulmonary tuberculosis. We used QuantiFERON-TB GOLD (QFT-G; Cellestis Ltd., Carnegie, Australia) as the diagnostic tool.

A 24-year-old male patient presented symptoms of melena and intermittent epigastric soreness. There were a few episodes of melena with the total amount estimated at 800 mL. The patient denied any fever, weight loss, and night sweating. He had a medical history of dust mite allergy and asthma about 7 years ago. The chest computed tomography (CT) scan taken 1 year ago showed eosinophilic infiltration. However, he did not receive any medication. He had neither a past clinical and radiological evidence of tuberculosis nor known exposure to tuberculosis.

The initial vital sign examination showed a blood pressure of 130/80 mm Hg, a regular heart rate of 88 beats per minute, a respiratory rate of 20 breaths per minute, and a body temperature of 36.8℃. His body weight was 73 kg and height was 168 cm. During the physical examination, a hyperactive bowel sound was heard, without any tender point in the abdomen. Moreover, there were no remarkable findings of palpable lymphadenopathy or mass.

Laboratory findings at presentation were as follows: normal complete blood count, liver function test, and electrolytes. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were increased to 14 mm/hr and 0.5 mg/dL, respectively. Paralytic ileus was seen on the abdominal X-ray film, and no remarkable finding was found on chest radiography.

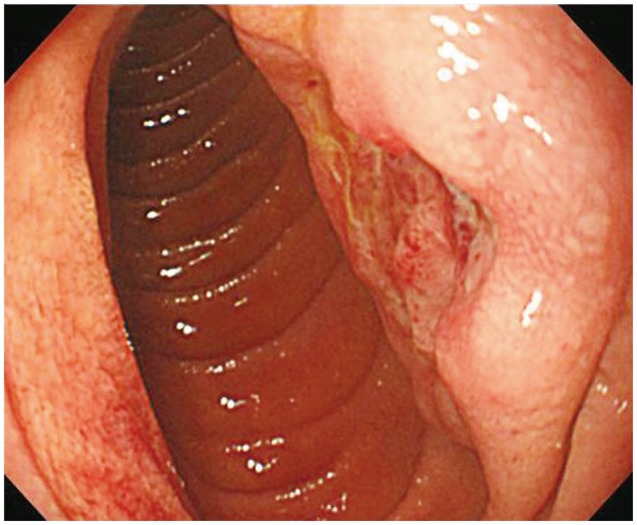

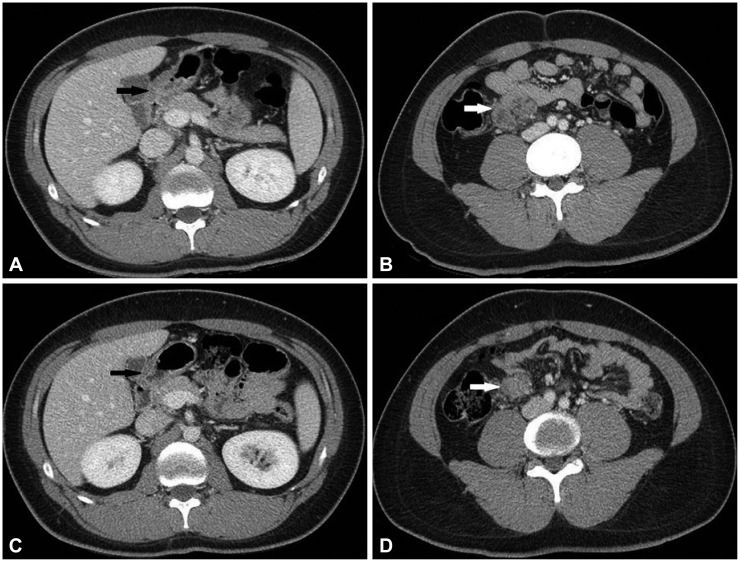

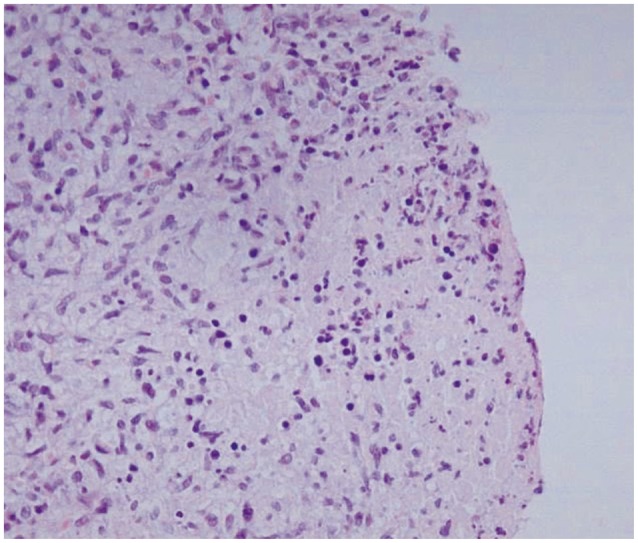

Initial gastroduodenoscopy showed an ulcerohypertrophic mass at the duodenal second portion, and multiple biopsies were performed (Fig. 1). Abdominal CT scan showed a lobular heterogeneous mass-like lesion abutting the inferior aspect of the duodenal second to proximal third portion, and multiple perilesional enlarged lymph nodes with some necrotic ch-anges (Fig. 2A, B). Therefore, we had to rule out a mucosal or submucosal origin of the tumor of the duodenum. Increased FDG uptake was seen at the duodenal second to third portion in fludeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)/CT. The maximum standardized uptake value (maxSUV) was 15.9, which highly suggested a primary malignant tumor. The biopsy showed acute and chronic inflammation with ulcer bed and granulomatous inflammation with necrosis. However, acid-fast bacilli staining was negative (Fig. 3). Follow-up endoscopy was performed 2 days after, and it showed an ulcerative mass at the second duodenum similar to the previous finding. Mycobacterium tuberculosis polymerase chain reaction (TB PCR) test was performed. Additionally, colonoscopy showed a normal colon and rectum.

The patient started food intake, and he did not complain of abdominal pain or melena. The result of TB PCR was negative. However, we started an antituberculosis regimen because of the suspicion of duodenal tuberculosis as the QFT-G test was positive. The HIV test was negative.

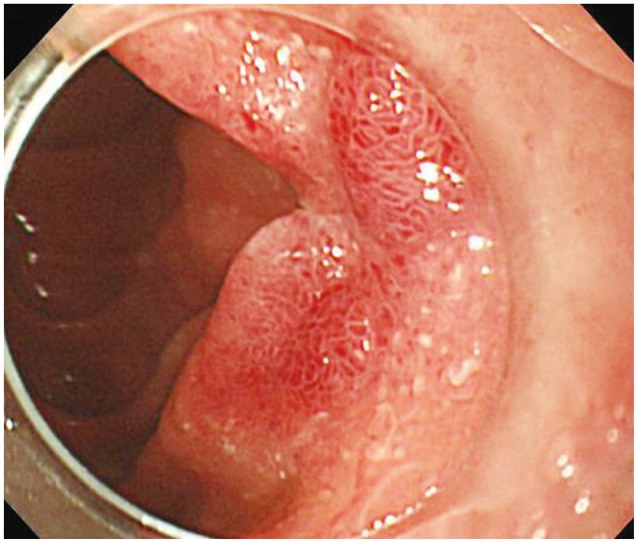

Six days after starting antituberculosis therapy, the patient was discharged. Three weeks later, he visited the outpatient clinic with a weight gain of 1 kg, and a follow-up endoscopy was performed. The endoscopic finding showed a scar change of the mass lesion with a regenerating epithelium (Fig. 4).

One month after the discharge, a follow-up CT was performed. It showed a slightly prominent, ill-defined soft tissue lesion in right lower quadrant mesentery, abutting the inferior aspect of the second to third duodenal portion, as well as multiple perilesional enlarged lymph nodes with some necrotic changes and fatty infiltration. Conglomerated tuberculosis lymphadenitis was suspected. A third CT was performed at 6 months after antituberculosis medication, which showed decrease in the extent of the previous conglomerated tuberculosis lymphadenitis (Fig. 2C, D). The patient has been treated with antituberculosis therapy for the last 6 months without any significant complication.

Extrapulmonary tuberculosis accounts for 15% to 20% of immunocompetent tuberculosis cases, and >50% of tuberculosis patients are human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positive.3,4 Gastrointestinal tuberculosis is the sixth most frequent site of extrapulmonary involvement. In gastrointestinal cases, the ileocecal region is the most commonly involved site.3,4

Furthermore, duodenal tuberculosis is rare even in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis and an endemic area of tuberculosis.2,5 An autopsy series reported a 0.5% incidence rate of gastroduodenal tuberculosis in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis.2 The possible cause of the rareness of duodenal tuberculosis is the relatively high acidic environment, few lymphoid tissues, and rapid transition of food material. For example, a study reported that long-term treatment with H2 blockers increased the incidence of gastroduodenal tuberculosis.5

It is difficult to recognize duodenal tuberculosis because of its vague, nonspecific symptoms or signs, and its nonspecific endoscopic or radiographic features. It can often be misdiagnosed as peptic ulcer disease, inflammatory bowel disease, or malignancy.

The most common presentations of duodenal tuberculosis are gastric outlet obstruction with pain and vomiting (60% to 70%). Cases of obstruction are mostly due to extrinsic compression by lymph nodes rather than due to an intrinsic lesion.3 Other symptoms include loss of appetite or weight (30%), upper gastrointestinal bleeding (26%), and fever or jaundice (8%).2,5 A few cases of fistulization of the bilioduodenal, aortoduodenal, and mesenteric artery to the duodenum have been reported.5

In our case, the patient presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and the endoscopic finding revealed an ulcerohypertropic mass of the duodenum without passage disturbance.

According to a review of the literature, endoscopic findings may reveal multiple features of ulcers, ulcerohypertrophic and hypertrophic. The most common form, about 60%, is the ulcerative lesion. It is circumferential and usually surrounded by an inflamed mucosa. Ulcerohypertrophic lesions, like our case, account for 30%. They show an inflammatory mass with an ulcerated and thickened mucosa. The least common form, hypertrophic lesion (about 10%), is characterized by scar, fibrosis, and pseudotumor formation.4,6

The radiologic feature of duodenal tuberculosis is also not specific. Mucosal ulceration, luminal narrowing, extrinsic compression, and proximal dilatation may be found in the barium test. In chest radiography, the evidence of pulmonary tuberculosis is up to 20%. Thickening of the duodenal wall, associated with lymph node enlargement, is often visible in CT and may be a clue to diagnosis.5

Because of the mass-like mucosal lesion with a high max-SUV in 18F-FDG PET/CT, we had to consider the possibility of adenocarcinoma or lymphoma despite the patient's young age. 18F-FDG PET/CT is a sensitive tool for detecting malignancy; however, a high FDG uptake is not specific for malignancy. Tissue affected by infection or autoimmune disease or granulomatous disease may show increased uptake of FDG, as these diseases are associated with a high glucose turnover. Thus, some inflammatory diseases, especially granulomatous disorders, including tuberculosis, can be mistaken for malignancy.7 Tian et al.8 reported three cases of multisite abdominal tuberculosis mimicking malignancy on ultrasonography and/or CT, 18F-FDG PET/CT. None of the patients had any past clinical or radiological evidence of tuberculosis and multiple lesions with a high 18F-FDG uptake. In two of them, the highest value of maxSUV was above 15 and 37, respectively. In all patients, after antituberculosis therapy, the second 18F-FDG PET/CT scan showed remission of all prior lesions. Therefore, a high uptake of 18F-FDG is not specific for malignancy, especially for the suspicion of tuberculosis.8 However, 18F-FDG PET/CT can be useful to detect malignancy and in the follow-up after treatment of intra-abdominal tuberculosis.

The evidence of acid-fast bacilli and granulomatous inflammation, may be a clue for diagnosis. However, only about 30% positivity of specific cytological and histopathological findings in gastrointestinal cases are reported.9 A comparative study on methods for the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis reported that the sensitivity and specificity were up to 82.6% and 95% for TB PCR, and 54.5% and 100% for tissue culture, respectively.10 Despite of the high sensitivity, these tests are not dependable because of having a broad sensitivity range. Therefore, diagnostic confirmation of gastrointestinal tuberculosis is difficult.4,6

Recently, researches showed that QFT-G has a diagnostic accuracy in extrapulmonary tuberculosis.11,12 A study reported high sensitivity (86%), specificity (100%), positive predictive value (100%), and negative predictive value (88%) of QFT-G in intestinal tuberculosis.12 Extrapulmonary tuberculosis cannot be ruled out in case of a negative QFT-G. However, since QFT-G has high false-negative rate, we referenced positive QFT-G as a diagnostic tool.11

As a rule, duodenal tuberculosis is rarely suspected without pulmonary tuberculosis. However, etiologies other than malignant tumor, such as tuberculosis, need to be considered even if endoscopic features resemble a malignant tumor with a strong suggestion from a high uptake in PET/CT.

A high index of suspicion for tuberculosis is required in any patient with gastrointestinal symptoms living in endemic areas such as Korea. In addition, we propose that QFT-G could be a useful tool in diagnosing extrapulmonary tuberculosis, as shown in our case.

References

2. Lamberty G, Pappalardo E, Dresse D, Denoël A. Primary duodenal tuberculosis: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2008; 108:590–591. PMID: 19051473.

3. Sharma MP, Bhatia V. Abdominal tuberculosis. Indian J Med Res. 2004; 120:305–315. PMID: 15520484.

4. Khuroo MS, Khuroo NS. Abdominal tuberculosis. In : Madkour MM, editor. Tuberculosis. Berlin: Springer;2004. p. 659–678.

5. Rao YG, Pande GK, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Gastroduodenal tuberculosis management guidelines, based on a large experience and a review of the literature. Can J Surg. 2004; 47:364–368. PMID: 15540690.

7. Rosenbaum SJ, Lind T, Antoch G, Bockisch A. False-positive FDG PET uptake: the role of PET/CT. Eur Radiol. 2006; 16:1054–1065. PMID: 16365730.

8. Tian G, Xiao Y, Chen B, Guan H, Deng QY. Multi-site abdominal tuberculosis mimics malignancy on 18F-FDG PET/CT: report of three cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2010; 16:4237–4242. PMID: 20806445.

9. Kim YS, Kim YH, Lee KM, Kim JS, Park YS. IBD Study Group of the Korean Association of the Study of Intestinal Diseases. Diagnostic guideline of intestinal tuberculosis. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2009; 53:177–186. PMID: 19835219.

10. Yönal O, Hamzaoğlu HO. What is the most accurate method for the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010; 21:91–96. PMID: 20549889.

11. Nishimura T, Hasegawa N, Mori M, et al. Accuracy of an interferon-gamma release assay to detect active pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008; 12:269–274. PMID: 18284831.

Fig. 1

Initial gastroduodenoscopy. An ulcerohypertrophic mass is noted at the duodenal second portion below the ampulla of Vater.

Fig. 2

Abdomen computed tomography. (A, B) The initial scan shows an ulcerohypertrophic lesion in the duodenal second to third portion (black arrow) and mass-like, multiple perilesional enlarged lymph nodes with some necrotic changes (white arrow). (C, D) After antituberculosis treatment for 6 months, the duodenal lesion (black arrow) and multiple lymph nodes (white arrow) were decreased.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download