Abstract

The use of colonoscopy for the screening and surveillance of colorectal cancer has increased. However, the miss rate of advanced colorectal neoplasm is known to be 2% to 6%, which could be affected by the image intensity of colorectal lesions. Image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE) is capable of highlighting lesions, which can improve the colorectal adenoma detection rate and diagnostic accuracy. Equipment-based IEE methods, such as narrow band imaging (NBI), Fujinon intelligent color enhancement (FICE), and i-Scan, are used to observe the mucosal epithelium of the microstructure and capillaries of the lesion, and are helpful in the detection and differential diagnosis of colorectal tumors. Although NBI is similar to chromoendoscopy in terms of adenoma detection rates, NBI can be used to differentiate colorectal polyps and to predict the submucosal invasion of malignant tumors. It is also known that FICE and i-Scan are similar to NBI in their detection rates of colorectal lesions. Through more effective and advanced endoscopic equipment, diagnostic accuracy could be improved and new treatment paradigms developed.

Colonoscopy has been used for colorectal cancer screening worldwide. However, the miss rate for advanced colorectal adenoma and cancer is known to be 2% to 6%.1 The locations of lesions, the technique of the endoscopist, and normal colorectal lesion image intensity are associated with the miss rate of colorectal adenoma and cancer.

Image-enhanced endoscopy (IEE) highlights lesions, which can improve the detection rate and diagnostic accuracy for colon polyps. IEE methods can be classified into dye-based (chromoendoscopy), and equipment-based using optical techniques.2 Using a visual filter and magnification, equipment-based IEE is used to observe the mucosal epithelium of the microstructure and the capillaries of the lesion. In addition, lesions can be evaluated by IEE though the measurement of fluorescence intensity emitted in tissues. In this section, the role of equipment-based IEE in the detection and estimation of histological findings for colorectal polyps will be discussed.

Narrow band imaging (NBI) separates white light into red, green, and blue using a special optical filter, and reconstructs the image while enhancing blue light, which has a relatively short wavelength.3,4 Blue light penetrates the mucosal surface, and is reflected at the mucosal surface, highlighting the superficial vasculature. Since mucosal hemoglobin selectively absorbs blue light, and the mucosa surrounding blood vessels reflects it, the contrast of the image is increased and the mucosal micro-vessel architecture can be estimated in fine detail. In the colon and rectum, microvessels form a ring, and each ring surrounds its respective gland. A deformed microvessel suggests a deformed neoplastic gland. Neoplastic changes result in a change in the form, density, and size of microvessels, and colorectal lesions can therefore be diagnosed.5

Since Hirata et al.6 reported that chromoendoscopy is similar to NBI in colorectal adenoma detection, six large-scale studies have been reported. Three of them demonstrated that NBI in fact has a higher adenoma detection rate.7,8,9 The adenoma detection rate of NBI is 27% to 40%. In particular, the detection of diminutive adenomas was the most improved. However, in a meta-analysis, the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of NBI were not significantly different from those of chromoendoscopy.10

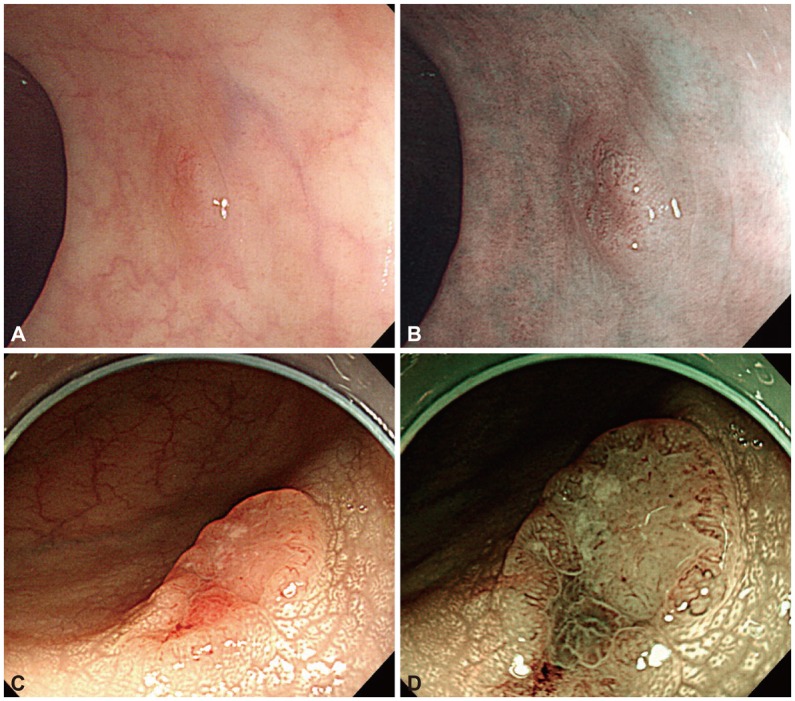

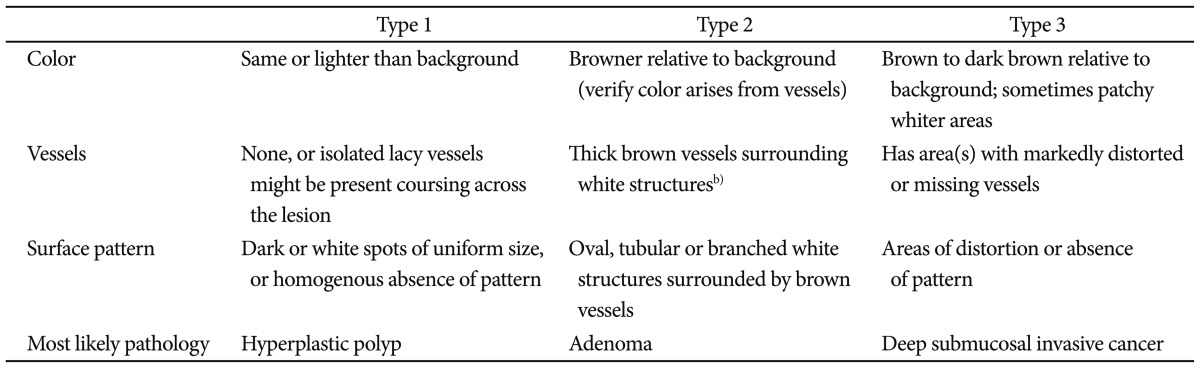

According to the surface color, capillary shape, and surface structure of the colorectal mucosa, several NBI classifications have been proposed.11,12 Based on the classification type, NBI could be helpful in the differentiation between colorectal adenomas and hyperplastic polyps. Recently, to create an easy-to-use NBI classification system, professionals around the world have developed the NBI international colorectal endoscopic (NICE) classification, which is based on surface color, the structure of blood vessels, and surface structure (Table 1).13 It has been reported that NICE is useful in the pathologic diagnosis of lesions.13,14

Fig. 1 shows two cases classified by NICE, representing a benign neoplasm (Fig. 1A, B) and submucosal invasive colon cancer (Fig. 1C, D).

A meta-analysis of several studies concerning the differentiation between colorectal adenomas and hyperplastic polyps showed that the accuracy of predictions of lesion pathology were 62% to 93% for NBI, 65% to 82% for while light endoscopy (WLE), and 69% to 96% for chromoendoscopy.10,15 The accuracy of pathological prediction by NBI was higher than that of WLE, and similar to that of chromoendoscopy.

In terms of the prediction of the invasion of malignant tumors with NBI, it has been reported that the density and regularity of the vascular structure are useful.11,16,17,18 Wada et al.18 have reported that the vascular structures of submucosal invasive carcinoma are irregular, and that they cannot be classified by the type of blood vessel. Depending on vascular structural findings, the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnosis of submucosal invasive cancer were 100% and 95.8%, respectively.

Fujinon intelligent color enhancement (FICE) emphasizes subtle changes of the mucosal surface through the reconstruction of a certain wavelength (computed spectral estimation technology), without using an optical filter such in NBI.19 FICE utilizes a simple switching operation to create the various wavelengths, and can choose the most appropriate wavelength to produce the image of the digestive tract.

For the differentiation of colorectal adenomas from hyperplasic polyps, Pohl et al.20 reported that the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of FICE were 90% to 97%, 74% to 80%, and 83% to 90%, respectively, and were better than those of WLE. However, FICE was not significantly different from chromoendoscopy in the differentiation of adenomas and nonneoplastic polyps.21

i-Scan utilizes the same spectral estimation technology as FICE technology, and applies a digital color filter to images to emphasize lesions. In comparisons of i-Scan with NBI and high-resolution colonoscopy, i-Scan was similar in the differential diagnosis of colon polyps and the prediction of pathological results. This revealed that i-Scan is also helpful in the differential diagnosis and prediction of the pathology of colorectal lesions.22,23

Equipment-based IEE methods such as NBI, FICE, and i-Scan, are useful for the detection and differential diagnosis of colorectal tumors. Despite the adenoma detection rate of NBI being similar to that of chromoendoscopy, NBI can be used to differentiate colorectal polyps and to predict the submucosal invasion of malignant tumors. Despite a lack of studies, it is known that FICE and i-Scan are both similar to NBI in the detection rate of colorectal lesions. To successfully use equipment-based IEE, endoscopists must first be aware of the features of the devices involved, and with the device's uses, applications, and limitations. In the future, diagnostic accuracy could be improved, and new treatment paradigms developed through more effective and advanced endoscopic equipment.

References

1. Bressler B, Paszat LF, Chen Z, Rothwell DM, Vinden C, Rabeneck L. Rates of new or missed colorectal cancers after colonoscopy and their risk factors: a population-based analysis. Gastroenterology. 2007; 132:96–102. PMID: 17241863.

2. Kaltenbach T, Soetikno R. Image-enhanced endoscopy is critical in the detection, diagnosis, and treatment of non-polypoid colorectal neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2010; 20:471–485. PMID: 20656245.

3. Gono K, Igarashi M, Obi T, Yamaguchi M, Ohyama N. Multiple-discriminant analysis for light-scattering spectroscopy and imaging of two-layered tissue phantoms. Opt Lett. 2004; 29:971–973. PMID: 15143644.

4. Kuznetsov K, Lambert R, Rey JF. Narrow-band imaging: potential and limitations. Endoscopy. 2006; 38:76–81. PMID: 16429359.

5. Emura F, Saito Y, Ikematsu H. Narrow-band imaging optical chromocolonoscopy: advantages and limitations. World J Gastroenterol. 2008; 14:4867–4872. PMID: 18756593.

6. Hirata M, Tanaka S, Oka S, et al. Magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging for diagnosis of colorectal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 65:988–995. PMID: 17324407.

7. East JE, Suzuki N, Stavrinidis M, Guenther T, Thomas HJ, Saunders BP. Narrow band imaging for colonoscopic surveillance in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer. Gut. 2008; 57:65–70. PMID: 17682000.

8. Rastogi A, Bansal A, Wani S, et al. Narrow-band imaging colonoscopy: a pilot feasibility study for the detection of polyps and correlation of surface patterns with polyp histologic diagnosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:280–286. PMID: 18155210.

9. Inoue T, Murano M, Murano N, et al. Comparative study of conventional colonoscopy and pan-colonic narrow-band imaging system in the detection of neoplastic colonic polyps: a randomized, controlled trial. J Gastroenterol. 2008; 43:45–50. PMID: 18297435.

10. van den Broek FJ, Reitsma JB, Curvers WL, Fockens P, Dekker E. Systematic review of narrow-band imaging for the detection and differentiation of neoplastic and nonneoplastic lesions in the colon (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 69:124–135. PMID: 19111693.

11. Aihara H, Saito S, Tajiri H. Rationale for and clinical benefits of colonoscopy with narrow band imaging: pathological prediction and colorectal screening. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2013; 28:1–7. PMID: 23053681.

12. Ng SC, Lau JY. Narrow-band imaging in the colon: limitations and potentials. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011; 26:1589–1596. PMID: 21793916.

13. Hewett DG, Kaltenbach T, Sano Y, et al. Validation of a simple classification system for endoscopic diagnosis of small colorectal polyps using narrow-band imaging. Gastroenterology. 2012; 143:599–607.e1. PMID: 22609383.

14. Hayashi N, Tanaka S, Hewett DG, et al. Endoscopic prediction of deep submucosal invasive carcinoma: validation of the narrow-band imaging international colorectal endoscopic (NICE) classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013; 78:625–632. PMID: 23910062.

15. Fujiya M, Kohgo Y. Image-enhanced endoscopy for the diagnosis of colon neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013; 77:111–118.e5. PMID: 23148965.

16. Sano Y, Ikematsu H, Fu KI, et al. Meshed capillary vessels by use of narrow-band imaging for differential diagnosis of small colorectal polyps. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 69:278–283. PMID: 18951131.

17. Kanao H, Tanaka S, Oka S, Hirata M, Yoshida S, Chayama K. Narrow-band imaging magnification predicts the histology and invasion depth of colorectal tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 69(3 Pt 2):631–636. PMID: 19251003.

18. Wada Y, Kudo SE, Kashida H, et al. Diagnosis of colorectal lesions with the magnifying narrow-band imaging system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 70:522–531. PMID: 19576581.

19. ASGE Technology Committee. Song LM, Adler DG, et al. Narrow band imaging and multiband imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:581–589. PMID: 18374021.

20. Pohl J, Nguyen-Tat M, Pech O, May A, Rabenstein T, Ell C. Computed virtual chromoendoscopy for classification of small colorectal lesions: a prospective comparative study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008; 103:562–569. PMID: 18070234.

21. Pohl J, Lotterer E, Balzer C, et al. Computed virtual chromoendoscopy versus standard colonoscopy with targeted indigocarmine chromoscopy: a randomised multicentre trial. Gut. 2009; 58:73–78. PMID: 18838485.

22. Lee CK, Lee SH, Hwangbo Y. Narrow-band imaging versus I-Scan for the real-time histological prediction of diminutive colonic polyps: a prospective comparative study by using the simple unified endoscopic classification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 74:603–609. PMID: 21762907.

23. Basford PJ, Longcroft-Wheaton G, Higgins B, Bhandari P. High-definition endoscopy with i-Scan for evaluation of small colon polyps: the HiSCOPE study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014; 79:111–118. PMID: 23871094.

Fig. 1

(A, C) White light (WLE) and (B, D) narrow-band imaging (NBI) of two colonic neoplastic lesions. (A) WLE showing a 6-mm lesion in the sigmoid colon. (B) NBI demonstrating thick brown vessels and a branched surface, compatible with NBI international colorectal endoscopic (NICE) type 2. After snare polypectomy of the lesion, microscopic evaluation showed tubular adenoma with low-grade dysplasia. (C) WLE showing a 1.5-cm slightly elevated lesion with a central depression on the mid ascending colon. (D) NBI showing a distorted surface and missing vessels, compatible with NICE type 3. On histologic evaluation of the resected lesion, an adenocarcinoma that invaded into the submucosal layer was found.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download