Abstract

Acute variceal bleeding could be a fatal complication in patients with liver cirrhosis. In patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis accompanied by ascites or hepatic encephalopathy, acute variceal bleeding is associated with a high mortality rate. Therefore, timely endoscopic hemostasis and prevention of relapse of bleeding are most important. The treatment goals for acute variceal bleeding are to correct hypovolemia; achieve rapid hemostasis; and prevent early rebleeding, complications related to bleeding, and deterioration of liver function. If variceal bleeding is suspected, treatment with vasopressors and antibiotics should be initiated immediately on arrival to the hospital. Furthermore, to obtain hemodynamic stability, the hemoglobin level should be maintained at >8 g/dL, systolic blood pressure >90 to 100 mm Hg, heart rate <100/min, and the central venous pressure from 1 to 5 mm Hg. When the patient becomes hemodynamically stable, hemostasis should be achieved by performing endoscopy as soon as possible. For esophageal variceal bleeding, endoscopic variceal ligation is usually performed, and for gastric variceal bleeding, endoscopic variceal obturation is performed primarily. If it is considered difficult to achieve hemostasis through endoscopy, salvage therapy may be carried out while keeping the patient hemodynamically stable.

Acute variceal bleeding is a fatal complication in patients with liver cirrhosis. In patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis accompanied by ascites or hepatic encephalopathy, acute variceal bleeding is associated with a high mortality rate. Nearly 50% of patients with newly diagnosed liver cirrhosis have accompanying varices;1 every year, new varices are develop or the preexisting varices worsen in 7% of patients,2,3 and first bleeding occurs in 12% of patients each year.4 The risk factors for variceal bleeding include the size of the varix, a red color sign on the surface of the varix, and the degree of deterioration of liver function.5 Alcohol consumption is also a risk factor for variceal bleeding. In a study on patients with large varices showing the red color sign and with a grade higher than F2, the accumulated bleeding rate after 2 years was higher at 57% in patients who continued to drink compared with 35% in patients who were abstinent.6 The 6-week mortality rate due to variceal bleeding is 15% to 20%, and in patients with severe decompensated liver cirrhosis of higher than Child-Turcotte-Pugh (Child-Pugh) grade C, the mortality rate increases up to 30%.7,8,9 Therefore, in patients with acute variceal bleeding, timely endoscopic hemostasis and prevention of rebleeding is most important. The treatment goals for acute variceal bleeding are 1) correction of hypovolemia, 2) rapid achievement of hemostasis, 3) prevention of early rebleeding, 4) prevention of complications related to bleeding, and 5) prevention of deterioration in liver function.10 In this article, the authors discuss patients with acute variceal bleeding, methods to achieve hemostasis, and methods to prevent rebleeding and complications.

The first step of treatment in patients with bleeding is the evaluation of the severity of the bleeding, and the achievement of hemodynamic stability through the administration of adequate fluids and transfusion. However, in contrast to patients with nonvariceal bleeding, too much transfusion or administration of fluids in patients with variceal bleeding can aggravate the bleeding resulting from increased portal venous pressure due to increased intravascular volume, and complications such as pulmonary edema and ascites may occur after hemostasis has been achieved; thus, close attention is required. It is recommended that hemoglobin levels should be maintained at 8 to 10 g/dL,10 although it is better to maintain it at 8 g/dL.11 When the level of consciousness declines, or in case of massive hemorrhaging, the systolic pressure should be maintained at >90 to 100 mm Hg, heart rate <100/min, and central venous pressure from 1 to 5 mm Hg.12 Among patients with variceal bleeding, many have accompanying hepatic dysfunction due to liver cirrhosis and coagulation disorders from massive transfusion for bleeding; thus, transfusion of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) or platelet concentrate (PC) is necessary in many cases. If the platelet levels are <50,000/mm3, transfusion of FFPs or PCs may be considered;12 however, as it might have no clear effect in the improvement of coagulation functions and may only increase intravascular volume, the decision should be made with care. At least two intravenous lines should be kept open on the arms or legs for fluid administration. Insertion of a central venous line could increase patient burden and might cause complications such as pneumothorax; therefore, it should be performed only in patients whose intravenous lines are difficult to secure, and in other cases, central venous lines should be inserted depending on the hemodynamic status of the patient after the endoscopic therapy.13

Administration of splanchnic constrictors and antibiotics on arrival at the emergency room is recommended in patients suspected to have variceal bleeding.14 The agents used for hemostasis for patients with variceal bleeding are vasopressin or its analog terlipressin (triglycyllysine vasopressin), and somatostatin or its analog octreotide and vapreotide. These agents directly or indirectly contract the vessels of the gastrointestinal tract, thereby decreasing the vascular inflow to the portal vein, and decreasing the portal venous pressure resulting in hemostasis of variceal bleeding. Vasopressin is a potent splanchnic vasoconstrictor effective for achieving hemostasis of variceal bleeding; however, because of its cardiovascular adverse effects, it is currently not recommended for use as a single therapeutic agent. Combination therapy with vasopressin and nitroglycerin shows better hemostatic effects than vasopressin alone and is associated with a lower rate of cardiovascular complications.15 Terlipressin has a dual effect: systemic vasoconstriction effect and direct splanchnic vasoconstriction effect when degraded into vasopressin. It is the only therapeutic agent that has shown evidence of decreasing mortality rates in patients with acute variceal bleeding, and may be used alone, as it results in fewer cardiovascular complications.16 Terlipressin has a greater effect than placebo or vasopressin and results in similar hemostatic effects to balloon tamponade.17 In most cases, intravenous administration of 1 to 2 mg terlipressin is done initially, and then 1 to 2 mg is continuously injected every 4 to 6 hours. Somatostatin enables indirect splanchnic vasoconstriction by inhibiting vasodilatory peptides such as glucagon. Moreover, as somatostatin has little systemic vasoconstriction effects, its systemic adverse effects are predicted to be less common. It is more effective than placebo or vasopressin, and when used as a bridging therapy until endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL), it has similar hemostatic effects as balloon tamponade.18,19 The half-life of somatostain is very short, from 1 to 2 minutes; thus, continuous intravenous infusion is necessary. After the initial intravenous administration of 250 µg, it is mixed in a 5% dextrose solution and infused at 250 µg/hr (6 mg/day) continuously. Octreotide is an octapeptide containing four amino acid chains identical to somatostatin and works to decrease the porto-collateral circulation. As it has a longer half-life than somatostatin (1 to 2 hours), more stable administration is possible, and 0.025 to 0.05 mg is continuously infused. Administration of vasoconstrictors should be initiated as soon as possible in case variceal bleeding is suspected before endoscopy, and this administration is continued usually for 2 to 5 days after endoscopic treatment is completed to prevent rebleeding, although further studies are necessary to determine the adequate period.

In liver cirrhosis patients with variceal hemorrhage, bacterial infections such as spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are common. These bacterial infections are present in 35% to 66% of liver cirrhosis patients with variceal bleeding, and is a risk factor for early rebleeding.20 Prophylactic antibiotics can increase the survival rate;21 therefore, the administration of antibiotics in patients with variceal bleeding is essential and is performed as soon as the patient arrives at the hospital.22 Norfloxacin selectively works against the gram-negative bacteria of the gastrointestinal tract and is orally administered at a dose of 400 mg, twice daily, for 1 week.23 When oral administration of antibiotics are impossible, quinolones such as ciprofloxacin or ofloxacin may be administered intravenously. A study on decompensated liver cirrhosis patients with variceal hemorrhage reported that the administration of 1 g ceftriaxone once daily is more effective than oral norfloxacin.24 Systemic administration of antibiotics is usually done for 3 to 7 days; however, further study is necessary to determine the adequate period.

To achieve hemostasis, endoscopic treatment should be performed as soon as the patient with acute variceal bleeding gains hemodynamic stability. In a study of 210 patients with acute variceal bleeding and hemodynamic stability, performing endoscopic treatment at 4, 8, and 12 hours after arriving at the hospital did not significantly affect the mortality rate.25 However, in another study, performing endoscopic therapy after more than 15 hours after hospital arrival significantly increased the mortality rate.26 It is recommended that endoscopic treatment be performed as soon as possible, that is, within 12 hours, in patients with variceal bleeding;27 however, the decision to perform emergency endoscopic treatment should be made depending on the patient status, conditions at the hospital, and skills of the doctor. It should be decided on the basis of the vital signs and the amount of the hemorrhage, as well as whether there is active bleeding or not, which can be determined from the color of the vomited blood and the frequency and amount of vomiting. In patients vomiting bright red blood, those with increasing amount of hematochezia, or those with unstable vital signs, endoscopic hemostasis should be achieved without delay. However, in patients with stable vital signs, if the patient is not considered to have signs of active bleeding (such as vomiting black red blood with food), has not fasted long enough, or has shown no hematemesis or hematochezia in the recent 12 hours, it may be more beneficial to delay the endoscopic treatment until a more skilled doctor can perform the procedure.13

Endoscopic treatment methods for esophageal varices include EVL and endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS). EVL is performed by placing the head of the endoscope with a rubber band ligation device over the varix to be ligated, suctioning the varix into the device, and tying the varix by discharging the rubber band (Fig. 1). For actively bleeding varices, it is better to perform prophylactic ligation on the varices within 5 to 10 mm to 5 cm from the esophagogastric junction. Previous accessories for endoscopic ligation allowed only one ligation to be performed at a time. Consequently, in case an attempt at ligation failed the first time owing to the lack of a clear visual field because of bleeding, it was difficult to perform successive ligations, and the endoscope had to be removed each time a ligation was attempted; thus, an overtube was used, which increased the risk of esophageal rupture. However, nowadays, accessories allowing multiple band ligations are being widely used; thus, these situations can be dealt with easily. In case it is difficult to find the bleeding focus because of the lack of a clear visual field, the cap on the tip of the endoscope can be controlled to apply pressure proximal and distal to the suspected bleeding point, to determine the bleeding focus. If the bleeding focus is not found despite this effort, ligation of the varix within 5 cm from the esophagogastric junction may slow the bleeding and allow the bleeding focus to be found easily. If suction of the mucosa into the cap is not sufficient or if fibrosis of the mucosa makes suction difficult, the band may not create a proper O-ring and may fall off, leading to failure of the ligation; therefore, caution must be taken. EIS is performed by injecting a sclerosant into the varix, and treatment is completed by inducing thrombosis of the varix. With this method, complete obliteration of the varix is most important to prevent recurrence. Various sclerosing agents such as 5% ethanolamine oleate (mainly used, injected in travenously) or sodium morrhuate are used. As 5% ethanolamine oleate has a strong hemolytic effect and may cause hemoglobinuria or renal failure when systemically injected in large doses, the dose to be used per treatment should be within 0.4 mL/kg.28 EVL and EIS showed a similar effect in achieving acute bleeding; however, fatality and complication rates were significantly higher with EIS.29 Therefore, as EIS does not show better treatment results than EVL and results in higher fatality and complication rates, it is not recommended as the first-line therapy for the endoscopic treatment of esophageal varices, and may be tried only in case EVL fails or if it is impossible to perform EVL.30

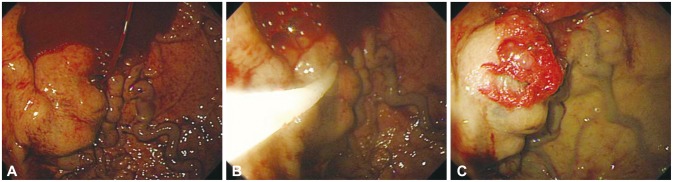

Gastric varices are known to be present in approximately 20% of patients with portal hypertension. The incidence of gastric variceal bleeding is lower than that of esophageal variceal bleeding; however, owing to the anatomical location of the varices and the characteristics of blood flow, the mortality rate is high. Gastric varices can be classified as gastroesophageal varices (GOVs), if the gastric varices form esophageal varices after crossing the esophagogastric junction, and as isolated gastric varices (IGVs), if they are not accompanied by esophageal varices. GOVs can be further classified as GOV1, which are relatively straight gastric varices formed on the lesser curvature, or GOV2, which are long curved gastric varices formed on the gastric fundus. IGVs can be further classified as IGV1, which are isolated varices formed on the gastric fundus, or IGV2, which are ectopic gastric varices formed on the gastric body, antrum, or pylorus.31 EVL has been reported to be effective in treating small gastric varices of the GOV1 or IGV1 form;32 however, as the gastric mucosa is thicker than the esophageal mucosa, the band may fall off more easily, and for larger varices or varices of the IGV form, combination therapy with EIS has to be done frequently because of the high risk of rebleeding. Further, obtaining a clear visual field with the fixed cap of the endoscope may be difficult because of the anatomical location, and ligation is impossible for large varices (>2 cm). Compared with esophageal varices, the risk of bleeding due to the formation of a large deep ulcer after band ligation is high, and there have been reports of gastric perforation due to excessive suction power. EIS with 5% ethanolamine oleate or ethyl alcohol is not recommended for the treatment of GOV2 or IGV1 because of the low success rate and high rebleeding and complication rates.33,34,35 For GOV2 and IGV1 forms of gastric variceal bleeding, endoscopic variceal obturation (EVO) is the first-line therapy (Fig. 2). Cyanoacrylate tissue adhesives such as N-butyl-cyanoacrylate (histoacryl), isobutyl-2-cyanoacrylate, or 2-octyl cyanoacrylate are used.36,37,38,39 Histoacryl is a nontoxic blue dye that acts as a potent adhesive when it makes contact with water in blood or tissues. The formed polymer then embolizes the blood vessel and obliterates the varix, thus exhibiting a rapid hemostatic effect. The foreign body reaction causes acute necrosis of the vascular endothelium, and the necrotized and fibrosed vessel walls fall off and become excreted from the body after 2 to 3 months.40 When injecting cyanoacrylate through the channel of the endoscope, it is recommended to lubricate the lumen of the channel with oil to avoid obstruction of the channel. When securing a clear visual field to allow a comfortable injection, too much flexion of the tip of the endoscope might cause the injection needle to perforate the channel of the endoscope. The conduit should be irrigated with 1 to 2 mL normal saline before puncturing the bleeding varix. When the size of the gastric varix is large, inserting the conduit too deep might cause a part of the conduit to be inserted into the varix with the needle tip, and this might prevent adequate obliteration of the varix after cyanoacrylate injection. Cyanoacrylate should be loaded into a syringe from an ampule right before injection since it may polymerize easily. Moreover, as it may solidify and damage the endoscope or channel, cyanoacrylate should be used after mixing it with lipiodol. If injected slowly after the puncture, the remaining saline in the channel is injected into the varix first, and this allows the operator to check whether the needle has been injected correctly into the varix. If the injection was not applied into the varix but into the vessel wall or tissue surrounding the varix, submucosal swelling will be visible, and in this case, the injection is stopped and puncture is be performed again (Fig. 3). If the needle is inserted correctly into the varix, the mixture of 0.5 mL cyanoacrylate and 0.5 mL lipiodol is injected rapidly. After injection of the solution mixture, 1 to 2 mL of normal saline is injected subsequently to flush out the remaining cyanoacrylate into the varix. When the injection is complete, the needle is removed from the varix, and normal saline is sprayed on the puncture site to allow the cyanoacrylate to solidify promptly. When removing the conduit for injection, it is better to wait for 20 seconds to allow adequate polymerization before removal, and during this time, the contents of the stomach should not be aspirated to prevent the channel lumen from becoming obstructed.41 If the cyanoacrylate content is too high, it could solidify within the conduit, impeding the injection, or it could solidify within the varix rapidly before the conduit is removed and impede the removal of the conduit. In contrast, if the cyanoacrylate content is too low, it may delay the solidification and cause systemic complications such as emboli. Thus, adequate dilution is crucial. Usually, 0.5 mL of both cyanoacrylate and lipiodol is mixed (1:1) for injection; however, in IGV1-type varices with a larger lumen, 60% to 70% concentrations may be used because the blood flow is faster. The amount of cyanoacrylate to be used is determined from the size of the varix; however, normally, 1 to 2 mL is used. Complication rates are related to the amount injected in one session; thus, it is better to keep the amount of injection to <2 mL per treatment. Performing ligation with a detachable snare is also possible to achieve hemostasis in gastric variceal bleeding, and with this method, it is easier to secure a clear visual field with EIS than with EVL, and it may be used for large varices >5 cm.42 However, the procedure has a risk of causing massive hemorrhaging, and a high degree of skill is required.43 The success rate for achieving hemostasis has been reported to be up to 83% to 100%.42,43

This is a temporary procedure that may be used in patients who are too hemodynamically unstable to undergo an endoscopic procedure, or in case endoscopic hemostasis has failed. A Sengstaken-Blakemore tube is usually used, and hemostasis could be achieved in up to 80% of cases of active bleeding. If hemostasis is not achieved within 2 hours, another treatment should be considered immediately, and as complications such as migration or aspiration of the tube, or necrosis or perforation of the esophagus could occur, it should not be used for >24 hours. If hemostasis is achieved and the patient is stabilized after balloon tamponade, further treatment such as radiologic intervention or surgical treatment should be considered.

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) can achieve hemostasis in up to 95% of acute variceal bleeding, and lowers the rebleeding rate. Early rebleeding is seen in 25% to 30% of cases, and these occur mostly because of stenosis or obstruction of the stent. As there is a high prevalence of deterioration in hepatic function or hepatic coma after the procedure, there is no difference in the mortality rate.

Gastric varices may be drained by using a gastrorenal shunt, the subphrenic or pericardial vein, and is drained to the inferior vena cava directly through a gastrorenal shunt in 75% of cases. A sclerosant is injected into gastric varices through the gastrorenal shunt for their obliteration, and gastric varices are eliminated in 86% to 100% of cases, with recurrence rates of as low as 0% to 2.7%.44,45 However, owing to the increase in portal pressure after the procedure, esophageal varices may worsen, and periodic follow-up endoscopic examinations are necessary.

In patients with Child-Pugh A/B liver cirrhosis with well-preserved liver functions, surgical treatment (distal splenorenal shunt, angiectomy) may be attempted. On the other hand, in patients with decompensated Child-Pugh B/C liver cirrhosis, liver transplantation may be considered.10

Acute variceal bleeding is a fatal complication in patients with liver cirrhosis, and it is most important to achieve hemostasis as soon as possible. Obtaining hemodynamic stability should be the first priority in patients with acute bleeding; however, in patients with variceal bleeding, excess administration of fluids or transfusions may cause complications such as ascites or pulmonary edema owing to the underlying deterioration in liver function. If variceal bleeding is suspected, medical therapy with vasopressors should be initiated immediately, and as there is a high risk of bacterial infection due to bleeding, prophylactic antibiotics should be administered. Currently, EVL is the primary therapy for esophageal variceal bleeding, and for gastric varices, EVO with cyanoacrylate is recommended. As the amount of bleeding is higher in variceal bleeding than in other gastrointestinal bleeding cases, obtaining a clear visual field may be difficult, impeding the endoscopic treatment. Moreover, as the general status of the patient is not good owing to the underlying liver disease, the patient might deteriorate rapidly during the procedure; thus, it is important for the operator to be familiar with the procedure, and to achieve hemostasis by finding the bleeding focus rapidly and precisely. Balloon tamponade, TIPS, balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration, and surgical treatment including liver transplantation may be attempted in case endoscopic treatment fails; thus, close observation of the patient's status is important during the procedure, and if it endoscopic treatment is deemed difficult, salvage therapy should be considered while hemodynamically stabilizing the patient.

References

1. Kovalak M, Lake J, Mattek N, Eisen G, Lieberman D, Zaman A. Endoscopic screening for varices in cirrhotic patients: data from a national endoscopic database. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 65:82–88. PMID: 17185084.

2. Groszmann RJ, Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J, et al. Beta-blockers to prevent gastroesophageal varices in patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005; 353:2254–2261. PMID: 16306522.

3. Merli M, Nicolini G, Angeloni S, et al. Incidence and natural history of small esophageal varices in cirrhotic patients. J Hepatol. 2003; 38:266–272. PMID: 12586291.

4. D'Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. Pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension: an evidence-based approach. Semin Liver Dis. 1999; 19:475–505. PMID: 10643630.

5. North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med. 1988; 319:983–989. PMID: 3262200.

6. Muntaner L, Altamirano JT, Augustin S, et al. High doses of beta-blockers and alcohol abstinence improve long-term rebleeding and mortality in cirrhotic patients after an acute variceal bleeding. Liver Int. 2010; 30:1123–1130. PMID: 20536715.

7. Villanueva C, Piqueras M, Aracil C, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing ligation and sclerotherapy as emergency endoscopic treatment added to somatostatin in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2006; 45:560–567. PMID: 16904224.

8. Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Bañares R, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. J Hepatol. 2008; 48:229–236. PMID: 18093686.

9. Bosch J, Thabut D, Albillos A, et al. Recombinant factor VIIa for variceal bleeding in patients with advanced cirrhosis: a randomized, controlled trial. Hepatology. 2008; 47:1604–1614. PMID: 18393319.

10. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. Clinical Practice Guideline for Liver Cirrhosis 2005. Seoul: The Korean Association for the Study of the Liver;2005.

11. Sarin SK, Kumar A, Angus PW, et al. Diagnosis and management of acute variceal bleeding: Asian Pacific Association for Study of the Liver recommendations. Hepatol Int. 2011; 5:607–624. PMID: 21484145.

12. The Korean Association for the Study of the Liver. Clinical Practice Guideline for Liver Cirrhosis: Update. Seoul: The Korean Association for the Study of the Liver;2011.

13. Cho SB. Variceal bleeding. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 43(Suppl 2):196–199.

14. Garcia-Tsao G, Bosch J. Management of varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2010; 362:823–832. PMID: 20200386.

15. Burroughs AK, Planas R, Svoboda P. Optimizing emergency care of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1998; 226:14–24. PMID: 9595599.

16. Lebrec D. Pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension: present and future. J Hepatol. 1998; 28:896–907. PMID: 9625326.

17. Fort E, Sautereau D, Silvain C, Ingrand P, Pillegand B, Beauchant M. A randomized trial of terlipressin plus nitroglycerin vs. balloon tamponade in the control of acute variceal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1990; 11:678–681. PMID: 2109729.

18. Chon CY, Jeong JI, Paik YH, et al. Comparison of somatostatin and vasopressin in the control of acute esophageal variceal hemorrhage: a prospective randomized trial. Korean J Hepatol. 2000; 6:468–473.

19. Lee JH, Lee SH, Koh KC, Paik SW, Rhee JC, Choi KW. Somatostatin vs. balloon tamponade for temporary hemostasis of bleeding esophageal varices before endoscopic variceal ligation. J Hepatol. 1999; 30(Suppl 1):190.

20. Goulis J, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Bacterial infection in the pathogenesis of variceal bleeding. Lancet. 1999; 353:139–142. PMID: 10023916.

21. Bernard B, Grange JD, Khac EN, Amiot X, Opolon P, Poynard T. Antibiotic prophylaxis for the prevention of bacterial infections in cirrhotic patients with gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999; 29:1655–1661. PMID: 10347104.

22. Rimola A, Garcia-Tsao G, Navasa M, et al. International Ascites Club. Diagnosis, treatment and prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a consensus document. J Hepatol. 2000; 32:142–153. PMID: 10673079.

23. Fernàndez J, Ruiz del, Gómez C, et al. Norfloxacin vs ceftriaxone in the prophylaxis of infections in patients with advanced cirrhosis and hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2006; 131:1049–1056. PMID: 17030175.

24. Cheung J, Soo I, Bastiampillai R, Zhu Q, Ma M. Urgent vs. non-urgent endoscopy in stable acute variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:1125–1129. PMID: 19337243.

25. Hsu YC, Chen CC, Wang HP. Endoscopy timing in acute variceal hemorrhage: perhaps not the sooner the better, but delay not justified. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:2629–2630. PMID: 19806094.

26. de Franchis R. Evolving consensus in portal hypertension. Report of the Baveno IV consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2005; 43:167–176. PMID: 15925423.

27. Kim SH. Variceal bleeding. In : 49th Seminar of Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; 2013 Aug 25; Goyang, Korea. Seoul: Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy;2013. p. 46–51.

28. Matsui T. Japanese guideline for gastrointestinal endoscopy: basic concept and control by Post-graduate Education Committee. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 24:349–350.

29. Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Michaletz-Onody PA, et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy as compared with endoscopic ligation for bleeding esophageal varices. N Engl J Med. 1992; 326:1527–1532. PMID: 1579136.

30. Jeong SW, Cho JY, Shin SJ, et al. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal variceal hemorrhage. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 40:71–83.

31. Sarin SK, Kumar A. Gastric varices: profile, classification, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989; 84:1244–1249. PMID: 2679046.

32. Shiha G, El-Sayed SS. Gastric variceal ligation: a new technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999; 49(4 Pt 1):437–441. PMID: 10202055.

33. Kim T, Shijo H, Kokawa H, et al. Risk factors for hemorrhage from gastric fundal varices. Hepatology. 1997; 25:307–312. PMID: 9021939.

34. Oho K, Iwao T, Sumino M, Toyonaga A, Tanikawa K. Ethanolamine oleate versus butyl cyanoacrylate for bleeding gastric varices: a nonrandomized study. Endoscopy. 1995; 27:349–354. PMID: 7588347.

35. Korula J, Chin K, Ko Y, Yamada S. Demonstration of two distinct subsets of gastric varices. Observations during a seven-year study of endoscopic sclerotherapy. Dig Dis Sci. 1991; 36:303–309. PMID: 1995266.

36. Sarin SK, Jain AK, Jain M, Gupta R. A randomized controlled trial of cyanoacrylate versus alcohol injection in patients with isolated fundic varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002; 97:1010–1015. PMID: 12003381.

37. Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Chen MH, Chiang HT. A prospective, randomized trial of butyl cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation in the management of bleeding gastric varices. Hepatology. 2001; 33:1060–1064. PMID: 11343232.

38. Tan PC, Hou MC, Lin HC, et al. A randomized trial of endoscopic treatment of acute gastric variceal hemorrhage: N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation. Hepatology. 2006; 43:690–697. PMID: 16557539.

39. Rengstorff DS, Binmoeller KF. A pilot study of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate injection for treatment of gastric fundal varices in humans. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004; 59:553–558. PMID: 15044898.

40. Soehendra N, Nam VC, Grimm H, Kempeneers I. Endoscopic obliteration of large esophagogastric varices with bucrylate. Endoscopy. 1986; 18:25–26. PMID: 3512261.

41. Seewald S, Mendoza G, Seitz U, Salem O, Soehendra N. Variceal bleeding and portal hypertension: has there been any progress in the last 12 months? Endoscopy. 2003; 35:136–144. PMID: 12561007.

42. Cipolletta L, Bianco MA, Rotondano G, Piscopo R, Prisco A, Garofano ML. Emergency endoscopic ligation of actively bleeding gastric varices with a detachable snare. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998; 47:400–403. PMID: 9609435.

43. Lee MS, Cho JY, Cheon YK, et al. Use of detachable snares and elastic bands for endoscopic control of bleeding from large gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 56:83–88. PMID: 12085040.

44. Ninoi T, Nishida N, Kaminou T, et al. Balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices with gastrorenal shunt: long-term follow-up in 78 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005; 184:1340–1346. PMID: 15788621.

45. Kim ES, Park SY, Kwon KT, et al. The clinical usefulness of balloon occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration in gastric variceal bleeding. Korean J Hepatol. 2003; 9:315–323.

Fig. 1

Endoscopic variceal ligation of esophageal varices. (A) Endoscopy reveals a red color sign on the esophageal varix through the transparent cap. (B) Variceal ligation is performed by placing the head of the endoscope with a rubber band ligation device over the varix to be ligated, suctioning the varix into the device, and tying the varix by discharging the rubber band.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download