This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

The most common cause of esophagorespiratory fistulas (ERFs) is associated with malignancy. The use of self-expandable metal stents is effective for the treatment of malignant ERFs, but benign ERF is rare, which is why its optimal treatment is not defined yet. There have been few reports describing benign esophagopleural fistula and its treatments in South Korea. Here, we report a rare case of spontaneous esophagopleural fistula, which was successfully treated by endoscopic placement of a membrane covered metal stent.

Go to :

Keywords: Esophagopleural fistula, Membrane covered metal stent

INTRODUCTION

Esophagorespiratory fistula (ERF) is an uncommon condition, despite of the anatomical proximity of these structures. Malignancy of esophagus, lung, or mediastinum is recognized as the most common cause. Causes of ERF development include direct tumor invasion and subsequent perforation or after radiation, laser therapy, chemotherapy, or pre-existing stents.

1 Benign ERF is rare and may be due to trauma or infection.

2 However, there have been few reports describing benign ERF and its treatments in South Korea. Here we report a case of nonmalignant esophagopleural fistula successfully treated by covered self-expanding metallic stents.

Go to :

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old man was admitted to Chungnam National University Hospital complaining right chest discomfort. He had 20 pack-years smoking history but had neither an operation history nor a medical history such as diabetes, hypertension, pulmonary tuberculosis, or hepatitis. Physical examination was unremarkable except for diminished respiratory sounds in the whole right lung field. The results of laboratory studies showed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 8,500/mm

2; hemoglobin of 12.5 g/dL; and platelet count of 164,000/mm

2. The serum biochemistry presented Na

+ of 140 mEq/L; K

+ 4.3 mEq/L; Cl

- 107 mEq/L; aspartate aminotransferase 19.5 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase 12.4 IU/L; total bilirubin 0.9 mg/dL; and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) 246 IU/L (all within normal ranges) with hypoalbuminemia (2.8 g/dL) and elevated serum creatinine level (1.65 mg/dL). Chest X-ray revealed right pleural effusion (

Fig. 1A). Pleural fluid analysis revealed pH of 7.0; red blood cell 3,200/mm

3; WBC 4,800/mm

3; total protein 4.0 g/dL; and LDH 2,246 IU/L compatible with exudative parapneumonic effusion, for which an antibiotic therapy was initiated with chest tube catheter insertion (

Fig. 1B). Thereafter food material was drained into the chest catheter. Esophagogram using gastrografin documented extravasation into the pleural cavity (

Fig. 2). Finally, upper endoscopy confirmed a large fistulous tract measuring 12 mm (

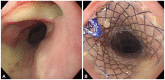

Fig. 3A). Stent insertion was considered as the first treatment due to the large fistula and pleuritis. A 14-cm long, 18-mm diameter covered Choo stent (MITech, Seoul, Korea) was deployed under direct vision (

Fig. 3B). A repeat endoscopic and radiologic study demonstrated neither extravasation nor migration. Three months after the stent insertion, the stent was easily removed by pulling removal snare with an alligator forceps (

Fig. 4A). Stent removal was uncomplicated. The patient remained asymptomatic (

Fig. 4B) at the subsequent follow-up 6 months after the stent removal.

| Fig. 1Chest X-ray showing (A) a huge left pleural effusion and (B) inserted chest tube catheter.

|

| Fig. 2Esophagogram showing apparent leakage from above the esophagogastric junction to the left pleural cavity.

|

| Fig. 3Endoscopy images showing (A) a purulent fistular tract opening in the lower esophagus and (B) fully expanded stent.

|

| Fig. 4Endoscopy images showing (A) the lower esophagus after stent removal and (B) complete closure of the esophagopleural fistula 6 months later.

|

Go to :

DISCUSSION

ERF is used to describe all fistulas located between the esophagus and the airway tree; however, esophagotracheal and esophagobronchial fistulas mostly account for the remaining ERF cases (3% to 11%) of esophagopulmonary fistulas.

3,

4 Accordingly, there have been very few previous reports concerning benign esophagopleural fistula and its treatment. Recent reports

5 regarding malignant esophagopulmonary fistula other than esophagotracheal and esophagobronchial fistulas showed technically successful stent placement outcome in 14 patients and complete fistula sealing in 12 patients (86%).

Known causes of acquired benign ERF include trauma and infection.

6-

8 The former lesions may be due to the increase in fistula caused by surgical procedures, blunt chest trauma, and prolonged ventilator assistance. The most common infectious cause is granulomatous disease, particularly tuberculosis. Other reported infectious causes include syphilis, mycotic disease, and Crohn's disease. In our case, the cause of the esophagopleural fistula was unclear. Evidence of malignancy was nearly undetectable from radiologic and tumor marker studies. Also a specific infectious agent was not isolated at the time of diagnosis and treatment.

Esophagopleural fistulas rarely heal spontaneously. Leaks of the esophagus are associated with a high mortality rate and need to be treated as soon as possible. Therapeutic options include surgical repair or resection or conservative management with antibiotic therapy and cessation of oral intake. Surgical correction requires aggressive and technically demanding procedures, results for which are uncertain. Endoscopic techniques to overcome this issue have been reported with obliterating agents, such as fibrin glue or cyan acrylic glue,

9-

11 endoscopic clip application,

12,

13 and endoscopic suturing device.

14,

15 Recently several types of covered and uncovered stents have been used in the treatment of ERFs.

Self-expanding metal stents (SEMSs) have been considered a safe and effective treatment for malignant dysphagia stricture, and fistula in inoperable patients.

16 Primarily SEMS has been used to palliate malignant state but are less commonly used in benign state due to concerns about their nonremovability and high complication rate. Recent technical improvement overcame these limitations. To evaluate fistula closure and stent patency or migration, repeat esophagogram at 1 week, then every 1 to 2 months after the procedure is suggested.

In our case, the cause of the esophagopleural fistula was unclear. However, esophagopleural fistula was successfully treated by an endoscopic stent insertion. Therefore, it appears that implantation of membrane-covered metal stents is an effective alternative for the treatment of esophagopleural fistula.

Go to :