This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Duodenal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare neoplasms. In this study, the medical records of 14 patients with duodenal NETs diagnosed at Chonnam National University Hospital from July 2001 to August 2011 were reviewed and analyzed retrospectively. Four patients were diagnosed in the first 5 years, and 10 patients were diagnosed in the latter 5 years of the study. Ten of 12 patients (83.3%) who underwent endoscopic biopsy were confirmed to have NET before resection. Endoscopic resection was performed in 12 patients, surgical resection in one patient, and regular follow-up in one patient who refused resection. None of the patients showed recurrence or distant metastasis. Duodenal NETs are increasingly observed and are mostly detected during screening upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Careful endoscopic examination and biopsy can improve the diagnostic yield of NETs. Most well-differentiated, nonfunctional duodenal NETs that are limited to the mucosa/submucosa can be treated effectively with endoscopic resection.

Go to :

Keywords: Neuroendocrine tumors, Endoscopic mucosal resection, Duodenum

INTRODUCTION

Duodenal neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are rare neoplasms that originate from the enterochromaffin cells of the gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine system. Duodenal NETs account for only 2.6% of NETs in the United States,

1 although they are being increasingly recognized with the more widespread use of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Although primary duodenal NETs grow slowly and show an indolent clinical behavior, they are potentially malignant. Owing to the late onset of clinical symptoms and delayed diagnosis of the tumor, there is a high possibility of distant metastasis that could hamper the long-term survival of many patients, leading to an unfavorable overall prognosis.

2 To date, limited information on the detection and diagnosis of this entity has been reported. We reviewed our institutional experience with duodenal NETs with regard to their clinical characteristics, including features, diagnosis, and treatments.

Go to :

CASE REPORT

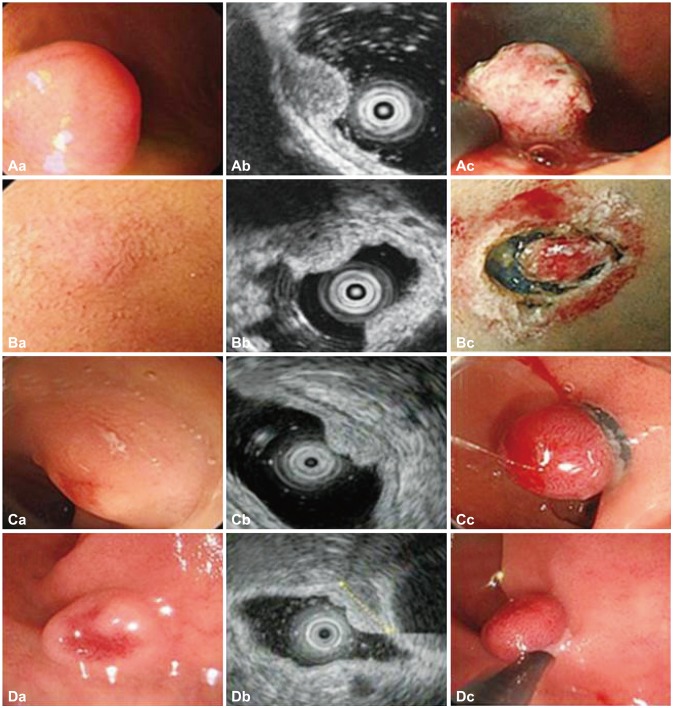

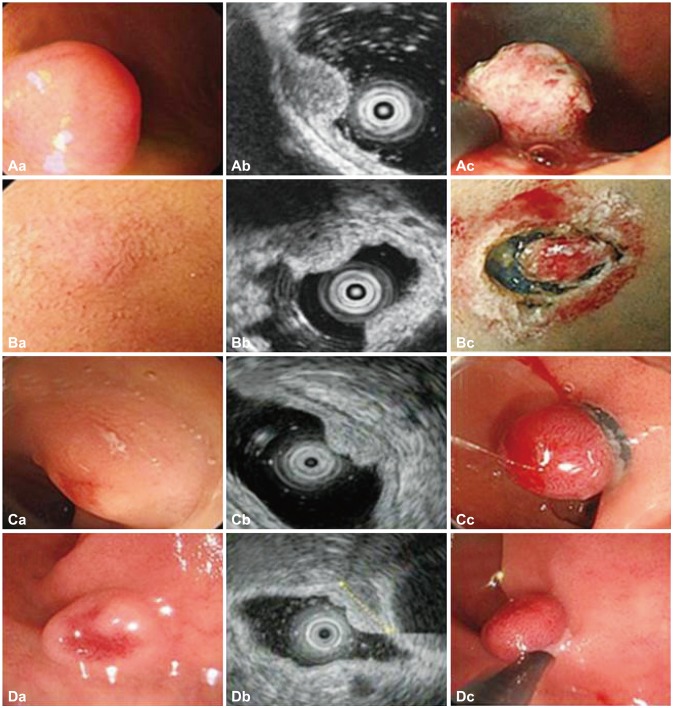

The medical archives at Chonnam National University Hospital from July 2001 to August 2011 were searched retrospectively for all patients with a proven pathologic diagnosis of primary duodenal NETs. The specimen was obtained by biopsy, endoscopic removal, and surgical resection. Endoscopic resection techniques consisted of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) (

Fig. 1). EMR was classified according to technique, such as EMR with a cap, EMR with ligation, or EMR with circumferential precutting. The pathologic diagnosis was established according to the characteristic histological morphology and architectural pattern, and reinforced by the immunohistochemical staining properties of the tumor. Data on the demographics, laboratory studies, diagnostic procedures, endoscopic features, treatment, and recurrence were extracted from the medical records.

| Fig. 1(A-D) Morphologic findings and resection techniques for duodenal neuroendocrine tumors (A, patient 6; B, patient 7; C, patient 9; D, patient 10). (Ac) Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) with circumferential precutting (EMR with precutting): after submucosal injection and circumferential mucosal incision, snaring was performed. (Bc) Endoscopic submucosal dissection: after submucosal injection, circumferential mucosal incision was performed. (Cc) EMR with ligation: band ligation was performed. (Dc) EMR: snaring was performed.

|

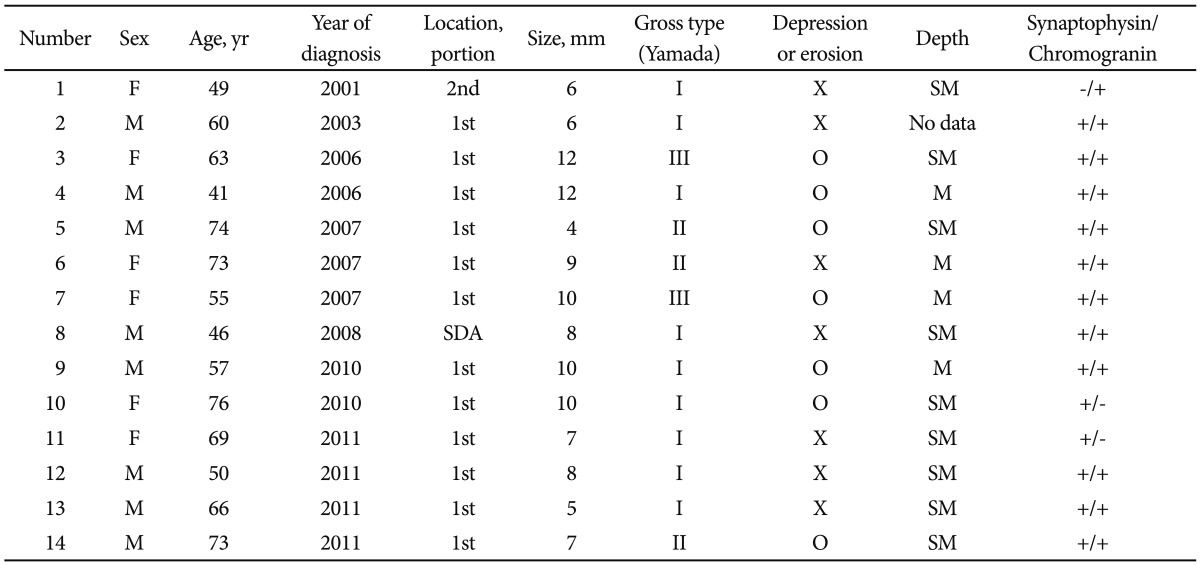

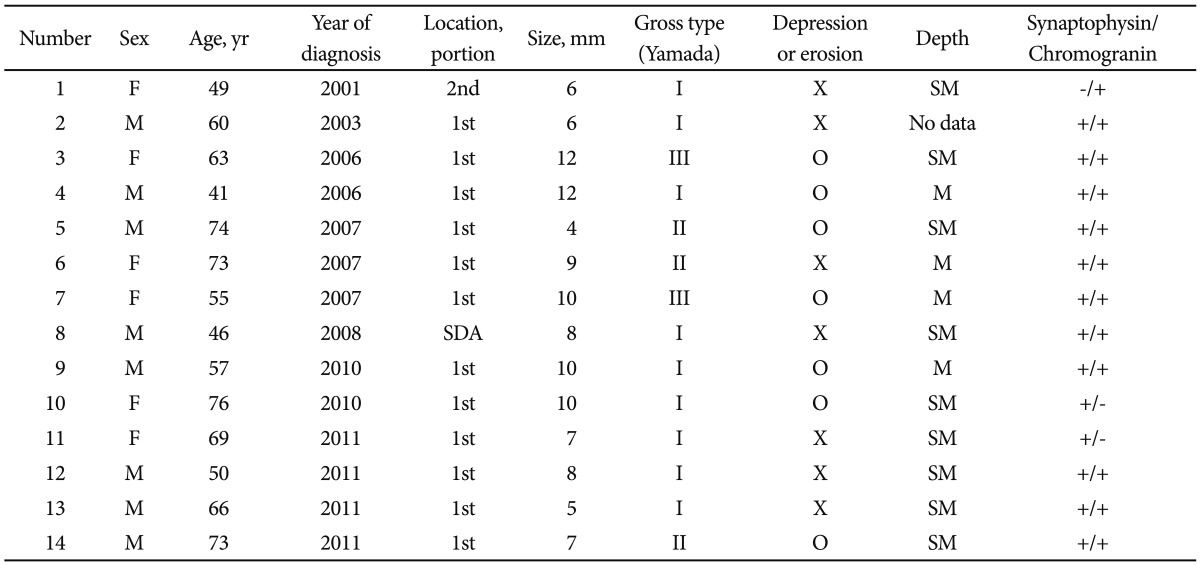

During the study period, four patients were diagnosed in the first 5 years, and 10 patients were diagnosed in the last 5 years. The 14 patients comprised eight men (57.1%) and six women (42.9%), with a mean age of 60.9±7.8 years (range, 41 to 76). Ten patients (71.4%) exhibited no symptoms and were evaluated by screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy. None of the patients exhibited the typical manifestations of carcinoid syndrome, such as paroxysmal flushing, diarrhea, and peripheral vasomotor symptoms. Three patients (21.4%) had dyspepsia or epigastralgia. One patient (7.1%) had melena and epigastric pain; this patient was later diagnosed with multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 1, with multiple gastric and duodenal ulcers.

Ten of 12 patients (83.3%) who underwent endoscopic biopsy were confirmed to have NET before resection. A central depression with erosion or ulcer was seen in seven cases (50%). Nine NETs (64.3%) were Yamada type I, three (32.4%) were Yamada type II, and two (14.3%) were Yamada type III. Two NETs (14.2%) showed a yellowish color, and erythema or increased vascularity was observed in seven NETs (50%). Twelve of 14 NETs (85.7%) were located at the first portion of the duodenum. One tumor (7.1%) was located in the superior duodenal angle, and the other (7.1%) was located at the second portion of the duodenum. The mean size of the tumors was 8.4±1.7 mm (range, 4 to 12). Twelve of 14 NETs were ≤1 cm, and the others were >1 cm. Urinary 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) levels were measured at the time of diagnosis in six patients. Four patients had a normal urinary 5-HIAA level (<6 mg/24 hours) and two had elevated urinary 5-HIAA values; after endoscopic resection, a decrease in 5-HIAA level was seen in both of these patients.

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) was performed in 10 patients. Most of the tumors were observed to have a well-defined hypoechoic and relatively homogeneous pattern. However, three tumors showed a different pattern (one hyperechoic, one isoechoic, one heterogeneous). All tumors were limited to the mucosa and/or the submucosa. No patient had lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis on abdominal computed tomography (CT), EUS, and chest CT.

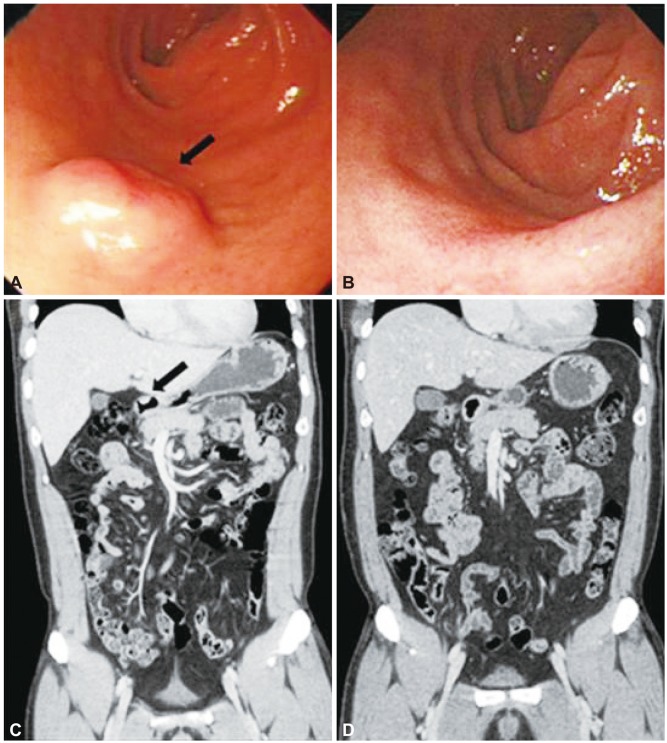

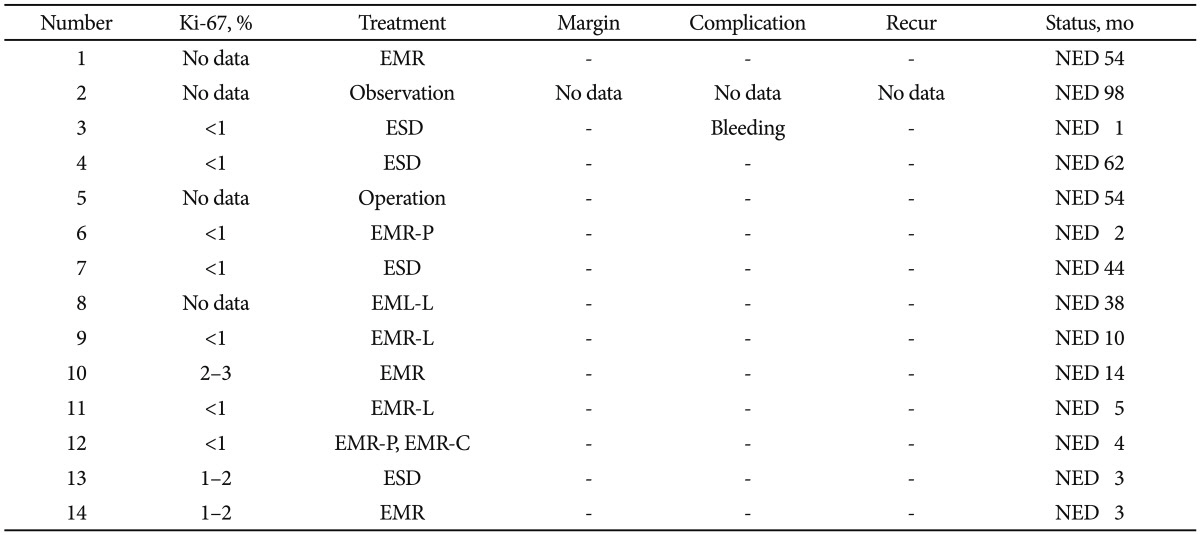

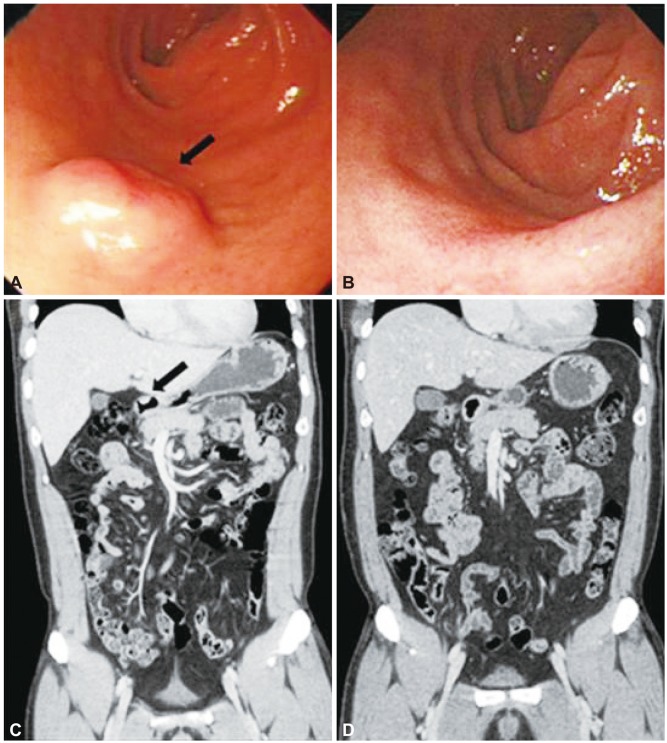

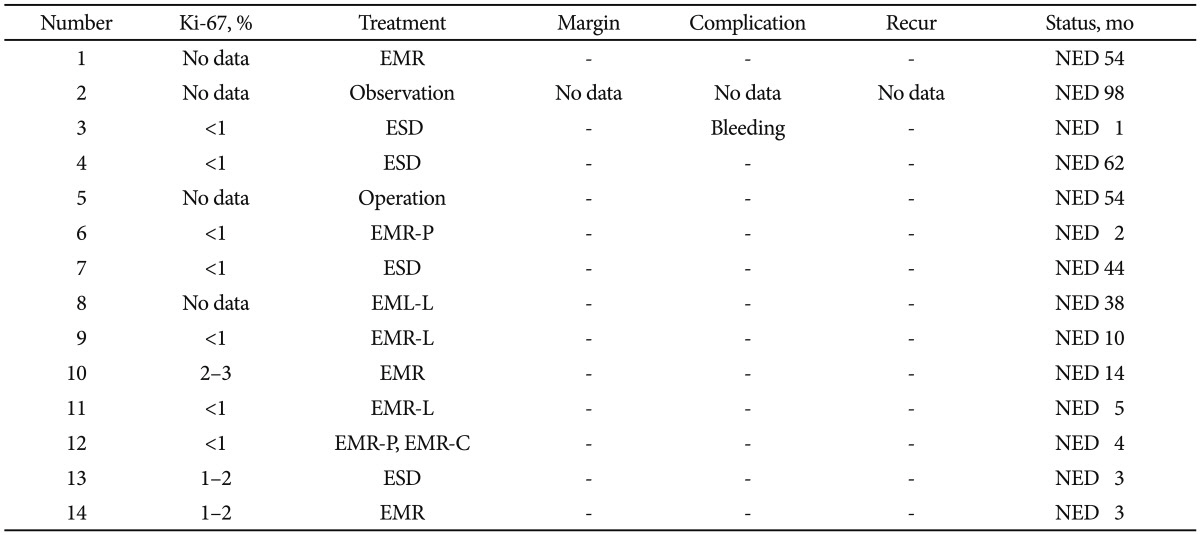

Endoscopic resection was performed in 12 of 14 patients (85.7%) (eight by EMR, four by ESD). Ten tumors (83.3%) were removed in one piece, and two tumors (26.7%) were removed in two pieces. The resection margins were negative in all patients. Immediate bleeding after resection developed in one patient but this was controlled by hemoclipping. No other serious complications such as late bleeding or perforation were noted. At a median follow-up period of 16±7 months, serial follow-up endoscopy and imaging studies, including abdominal CT, showed no evidence of disease progression (

Fig. 2). Surgical resection was performed in one patient with concomitant poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinoma. Radical subtotal gastrectomy with segmental duodenal resection was performed in this patient. All resected specimens showed a G1 histological grade and no infiltration of the muscularis propria or lymphovascular invasion. One patient refused resection and thus, was followed up regularly. A 5-mm polypoid lesion could no longer be found after the initial biopsy, and the imaging study during 99 months also showed no metastasis. Histologic and immunohistochemical analyses were performed in all patients. Thirteen of 14 NETs (92.8%) were positive for synaptophysin, 12 of 14 NETs (85.7%) were positive for chromogranin, and two of two NETs (100%) were positive for nonspecific enolase. All tumors showed a low proliferative rate (<3% of the Ki-67 labeling index). The results are summarized in

Tables 1,

2.

| Fig. 2(A-D) Endoscopic findings and coronal computed tomography (CT) scans before and after endoscopic resection (patient 4). (A, C) Endoscopy and CT image show a submucosal mass (black arrows). (B, D) Follow-up endoscopic and coronal CT images show no evidence of recurrence 62 months after resection.

|

Table 1

Survey of Endoscopic Features and Clinical Characteristics of the Patients with Duodenal Neuroendocrine Tumor

Table 2

Survey of Clinical Characteristics of Patients with Duodenal Neuroendocrine Tumor

Go to :

DISCUSSION

NETs originate from neuroendocrine cells throughout the body and occur most frequently (60% to 80%) in the gastrointestinal tract.

1,

3 NETs are rare, as they constitute <2% of all gastrointestinal malignancies.

4 Although uncommon, these tumors are increasing in incidence at a rate greater than that of other cancers.

1 The exact reason for this increase is not known but it might be related to the increased incidence of screening examinations and increased awareness among physicians, as well as to advances in diagnostic tools and treatments. At our institution, four patients were diagnosed in the first 5 years and 10 patients were diagnosed in the last 5 years of the study.

A previous study reported that reappraisal of the technical quality of initial endoscopic biopsies showed good subepithelial presentation in 35% of cases, thus permitting diagnosis.

5 In the current study, 10 of 12 patients (83.3%) were found to have NET by using a conventional-sized biopsy forceps at the initial endoscopy before resection. The diagnostic rate of endoscopic biopsy for NETs may be higher than that for other subepithelial lesions because NETs are considered epithelial neoplasms.

6,

7

Duodenal NETs are categorized according to the World Health Organization classification into well-differentiated NET, well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC; defined by the presence of metastases or infiltration of the muscularis propria or angioinvasion), and poorly differentiated NEC.

8-

10 A tumor node metastasis (TNM) classification based on tumor size, depth of invasion, and presence of lymph node metastases and/or distant metastases has been proposed and combined with a three-tiered grading system.

8-

10 Both G1 and G2 NETs are considered well-differentiated NETs, whereas poorly differentiated NEC is graded as G3. The risk factors for metastatic disease are angioinvasion, high mitotic count, high Ki-67 index, infiltration of the muscularis propria, size >2 cm, or metastatic spread to lymph nodes.

8-

10 Well-differentiated (G1), nonfunctional duodenal NETs that are limited to the mucosa/submucosa, up to 10 mm in size, and grow nonangioinvasively, can be endoscopically removed. These NETs carry a low risk for lymphatic or distant metastasis.

11 The recent increased use of EUS to assess duodenal NET invasion and the presence of possible lymph node metastases is particularly important in establishing NETs in this category.

12 EUS allows accurate TN staging of duodenal NETs.

13 EUS also accurately determines the layer of origin of the lesion and the internal echo pattern, which also adds to the differential diagnosis. EUS is necessary for the determination of endoscopic resectability.

As many of the duodenal NETs infiltrate the submucosa, various therapeutic endoscopic approaches have been considered. Nowadays, EMR is the most widely performed procedure.

14 Therapy is controversial for NETs of the duodenum that are nonfunctional, well-differentiated (G1), limited to the mucosa/submucosa, 10 to 20 mm in size, grow nonangioinvasively, and have not metastasized. Both endoscopic therapies and surgery are considered in this situation.

11 Controlled studies on the different approaches are lacking.

15 However, there is consensus that in operable patients, nonfunctional duodenal NETs >20 mm as well as all sporadic gastrinomas are indicated for surgical therapy.

16

Duodenal NETs are often diagnosed incidentally during a gastroduodenoscopy performed for other reasons.

11,

17 Most duodenal NETs are detected in the early, easily treatable stages (with a tumor diameter of ≤10 mm).

11,

17 Early small tumors are mostly nonfunctional (hormone inactive) and usually do not cause any discomfort.

In summary, duodenal NETs are increasing and are mostly detected during screening upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Careful endoscopic examination and biopsy can improve the diagnostic yield of these tumors. Most well-differentiated, nonfunctional duodenal NETs that are limited to the mucosa/submucosa can be treated effectively with endoscopic resection.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download