Abstract

Endoscopic management of symptomatic pancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) is now considered to be first line therapy. Expanded use of endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) techniques has resulted in increased applicability, safety, and efficacy of endoscopic transluminal PFC drainage. Steps include EUS-guided trangastric or transduodenal fistula creation into the PFC followed by stent placement or nasocystic drain deployment in order to decompress the collection. With the remarkable improvement in the available accessories and stents and development of exchange free access device; EUS drainage techniques have become simpler and less time consuming. The use of self-expandable metal stents with modifications to drain PFC has helped in overcoming some previously encountered challenges. PFCs considered suitable for endoscopic drainage include collection present for greater than 4 weeks, possessing a well-formed wall, position accessible endoscopically and located within 1 cm of the duodenal or gastric walls. Indications for EUS-guided drainage have been increasing which include unusual location of the collection, small window of entry, nonbulging collections, coagulopathy, intervening varices, failed conventional transmural drainage, indeterminate adherence of PFC to the luminal wall or suspicion of malignancy. In this article, we present a review of literature to date and discuss the recent developments in EUS-guided PFC drainage.

Pancreatic fluid collections (PFCs) can develop secondary to fluid leakage or liquefaction of pancreatic necrosis.1 PFCs are also seen in association with acute and chronic pancreatitis, abdominal trauma, and surgery.2-5 The Atlanta classification has been accepted as the current standard classification system.6,7 Other factors known to influence PFC creation include underlying pancreatic ductal damage, the severity of acute pancreatitis, and maturation of the collection with respect to the onset of acute pancreatitis.7-11 Abdominal pain, infected collection, gastric outlet or biliary obstruction, fluid leakage, fistulization, and enlargement of the PFC are all indications for drainage.7-11 Apart from endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided transluminal endoscopic drainage of PFCs, other alternative therapies include endoscopic transpapillary drainage, direct surgical drainage, and percutaneous drainage. Both surgical drainage and radiologically-guided percutaneous drainage are effective modalities for PFC drainage, but not without adverse events (7% to 37%).7,12-15 An indwelling catheter is required for the percutaneous technique and may lead to a new possible nidus for infection as well as a percutaneous fistula formation.16-18

Many tertiary care centers have adopted the endoscopic approach to PFC drainage as the preferred option as endoscopic drainage has been reported to have a clinical success rates of 70% to 87% with complication rates of 11% to 34%.7,19-21 In addition, endoscopic drainage of PFC can be accomplished with a transmural or transpapillary placement of plastic stents, however this option has fallen out of favor in most recent years.7,22

Conventional transmural drainage without EUS carries a high risk of perforation in the absence of an obvious, visible bulge.23,24 While bulging collections provide an easier target for the operator, nonbulging PFC are present in 42% to 48%.25,26 With EUS-guidance, entry into cysts has been shown to be safer.23 EUS has also provided an advantage for drainage of pancreatic abscesses and necrosectomy of organized liquefied necrotic collections in addition to the above described nonbulging PFCs.1,7,27,28

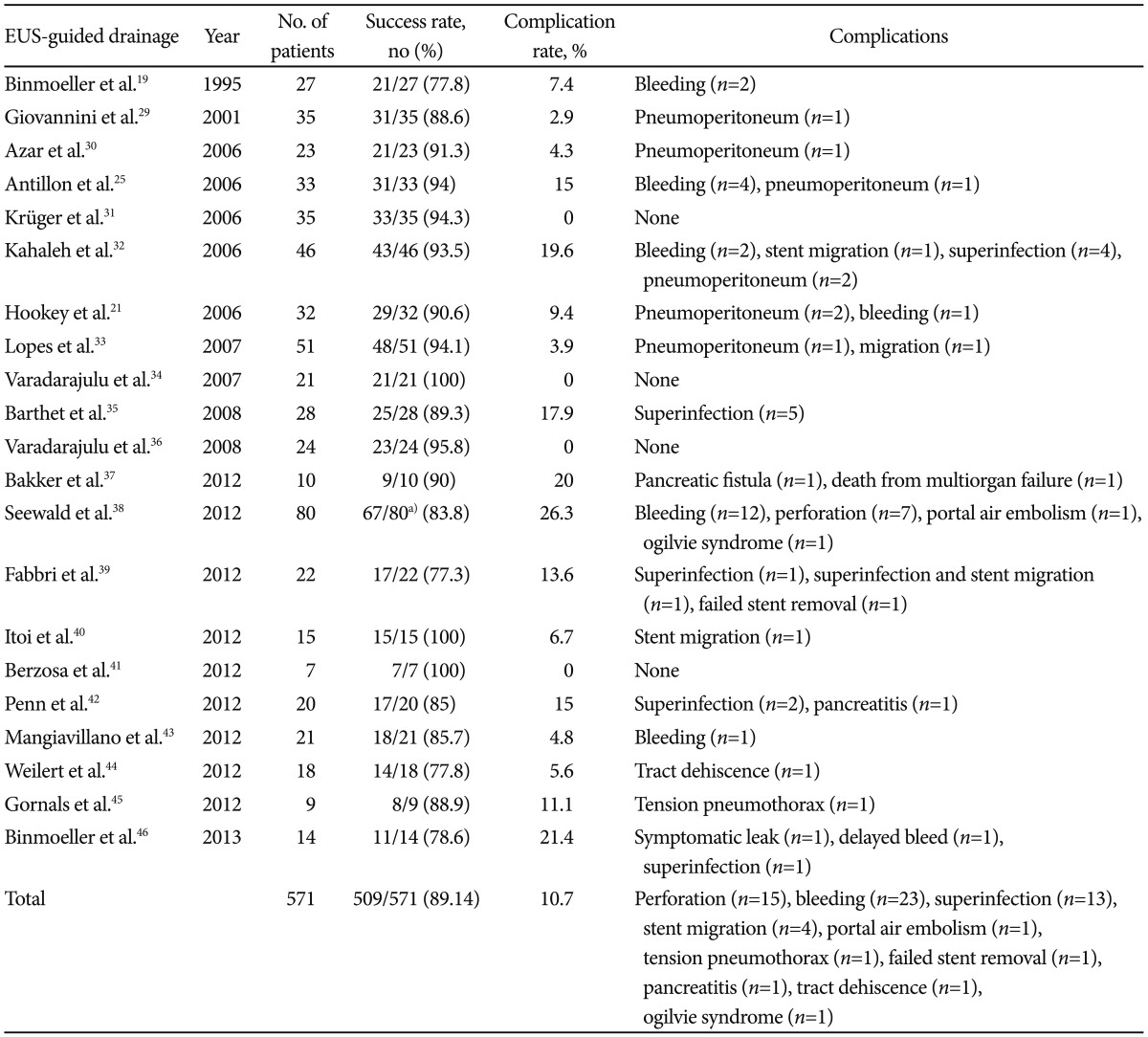

An extensive English language literature search was conducted on PubMed and Medline to identify the peer reviewed original and review articles. Key words included EUS, PFC, endoluminal, transluminal, transgastric, transduodenal, drainage, stenting, and adverse events. In this article, we present the data available reviewed up to February 2013. The references of pertinent studies and review articles were manually searched to identify additional relevant studies. The indication, procedural details, technical and clinical success rates, complications and limitations are discussed. The summary of studies included in the review is shown in Table 1.19,21,25,29-46 In addition, our experience with EUS-guided PFC drainage technique is also described.

PFC development in acute or chronic pancreatitis dictate different indications for drainage.23 Cross-sectional computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) imaging prior to drainage is essential in defining the patient's anatomy and determining an appropriate target window for intervention. It also permits exclusion of a cystic neoplasm in patients without a history of acute or chronic pancreatitis.28 When the fluid collection is not acutely responding to conservative management, drainage is indicated, especially if the patient has signs of sepsis. In chronic pancreatitis, drainage should be performed for symptomatic management including pain, gastric outlet obstruction, or biliary compression resulting in jaundice.23 Size alone has not yet been described as a sole indicator for PFC drainage.47

Nonbulging fluid collections, known portal hypertension/high pretest probability of bleeding, prior failed traditional transmural drainage, or the need to exclude cystic neoplasm are all indications to strongly consider EUS-guided drainage over other modalities.32,34,47,48 It is important to know if the collection is primarily of liquid contents or if there is a component of solid debris. We recommend assessing the main pancreatic duct at the time of PFC drainage with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) as patients with major main pancreatic duct leaks may require stent placement to bridge the leak.28,49

Endoscopic ultrasonography for drainage of PFCs should only be performed by physicians trained in both EUS and ERCP skill sets. It is also important to note that this procedure should only be performed in centers with available pancreaticobiliary surgeons and interventional radiologists in the event that a complication transpires.

Linear array echo-endoscopes with a channel size of at least 3 mm should be used to allow placement of larger 10 French stents.23,32 The GF-UCT 140-180 (Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA, USA) has a working channel of 3.7 mm and the EG 38 UT (Pentax, Tokyo, Japan) has a working channel of 3.8 mm. A 19 gauge (G) fine needle aspiration needle (Wilson-Cook, Winston-Salem, NC, USA) can be used for pseudocyst puncture to enable the insertion of a larger 0.035-in guidewire through the needle for pseudocyst drainage. Dilation of the fistula created can be performed using a wire-guided balloon or cystenterostome.26

The single step approach led to the development of instruments that utilize a 19 G stainless steel puncture needle (Grosse, Daldorf, Germany) loaded with a modified 7- or 10-Fr stent and a Teflon pusher catheter (Wilson-Cook).50,51 A needle wire device, introduced by Giovannini et al.,52 consists of a 0.035-in needle wire suitable for cutting current, a 5.5 Fr dilator and an 8.5 Fr stent (length 6 cm) with a pusher preassembled on the same catheter (Giovannini Needle Wire Oasis; Cook Endoscopy, Winston-Salem, NC, USA). Those products are, however, not currently available in the USA. Use of a novel exchange free access device (NAVIX; Xlumena Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) has been described recently by many authors.44-46 It enables access, tract dilation, and guidewire placement, reducing device exchanges.

As described above, abdominal CT or MRI (with contrast) should be obtained to describe the patient's anatomy as well as to aid in describing the collection's contents. Additionally, imaging helps to describe the relationship of the PFC with the surrounding lumen and vascular structures, and to discount any other underlying etiologies of PFC for which treatment may differ.23,47 Given that this is an invasive procedure, the patient should have a complete blood count to assess for thrombocytopenia as well as a screen for coagulopathy.

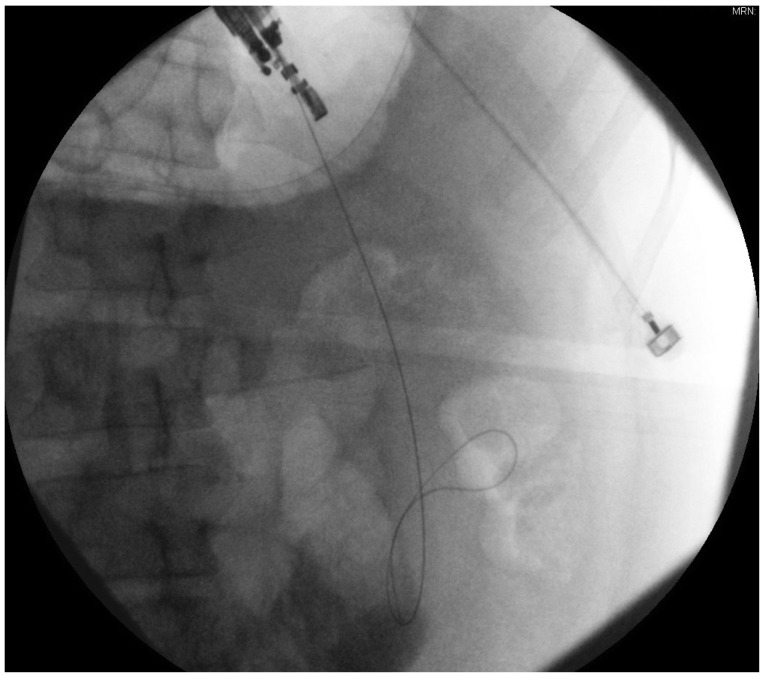

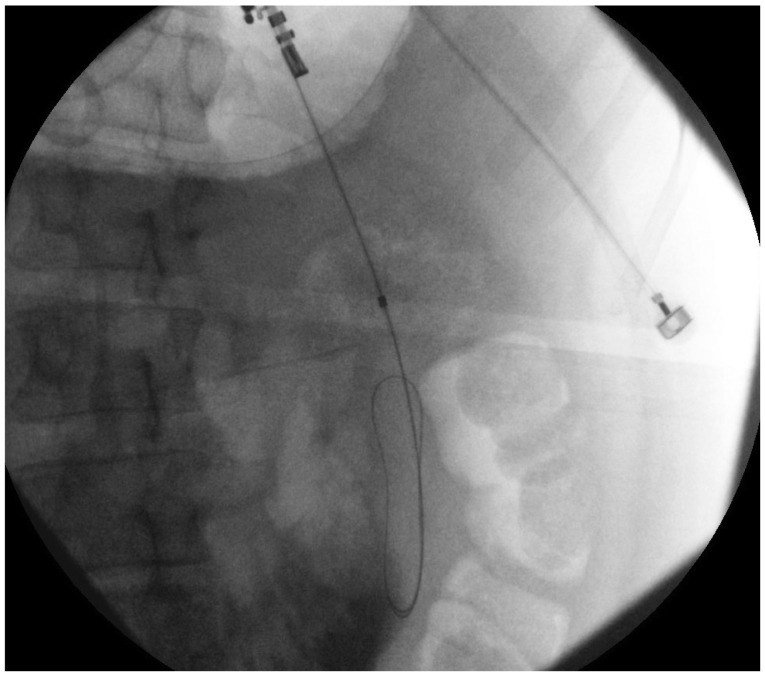

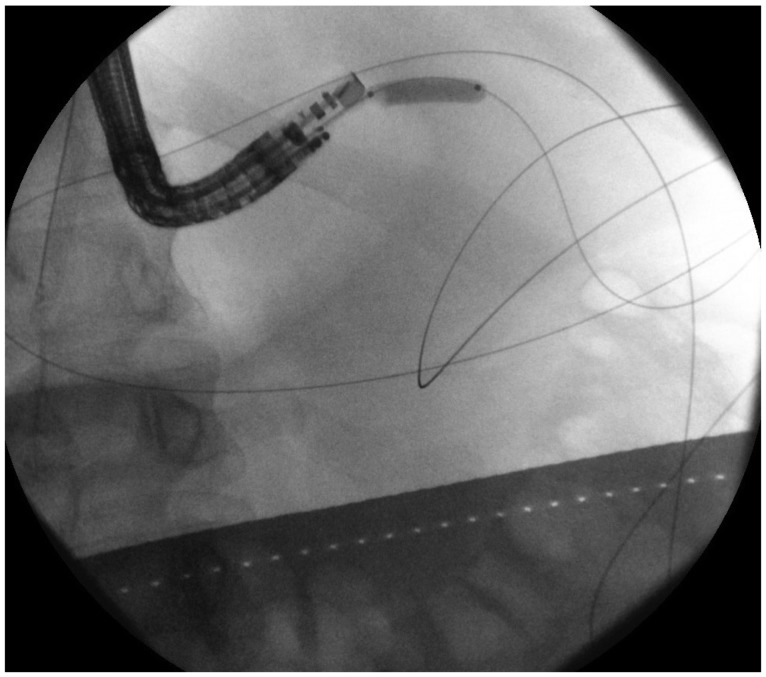

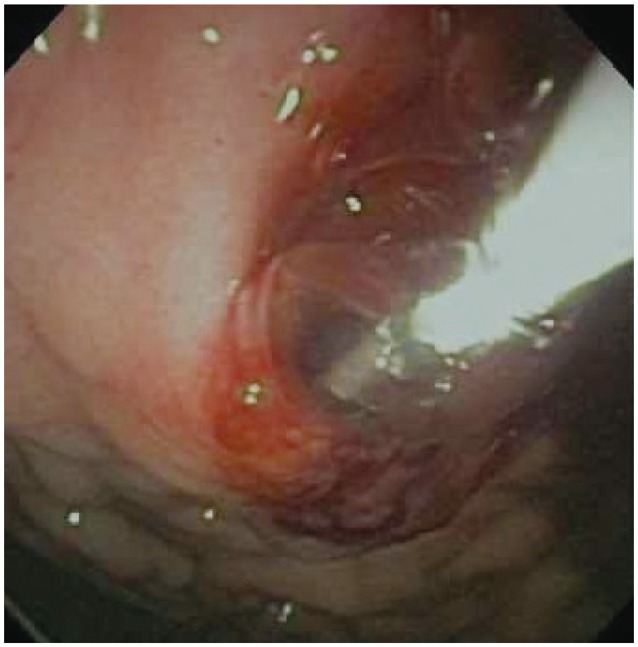

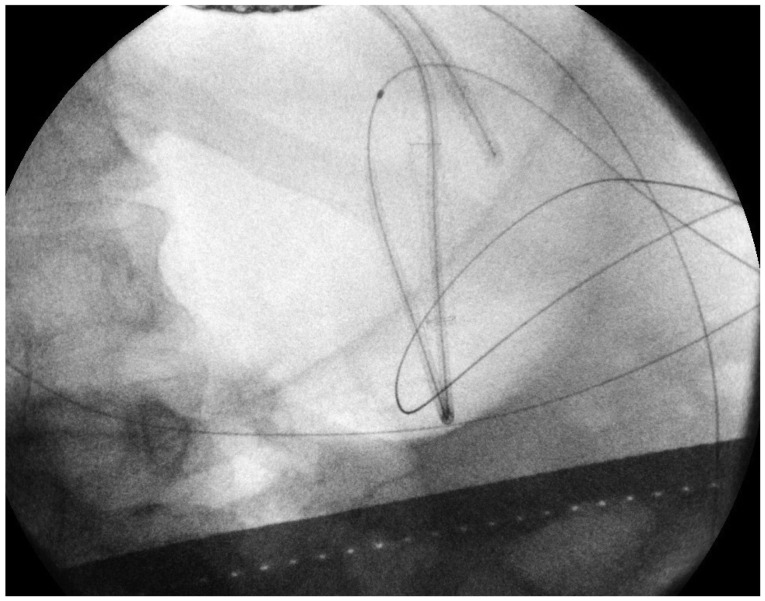

Using EUS, the PFC is first located. Color doppler ultrasound is then used to identify regional and surrounding vasculature. An intraluminal site, gastric or duodenal, is identified as closest to the PFC, preferably not more than 1 to 2 cm. A transesophageal approach has been attempted which was associated with tension pneumothorax.45 A fistula between the pseudocyst and the stomach or duodenum is created by introducing a 19 G needle directly into the PFC (Fig. 1). A sample of cyst contents is aspirated and submitted for biochemical analysis, and if infection is suspected, a sample should be sent for gram stain and culture. Contrast filling of the pseudocyst can be conducted under direct fluoroscopy to assess and document size, boundaries, and determine if communication with the pancreatic duct is apparent. Drainage can be achieved by using either the needle knife technique or the Seldinger technique. In the Seldinger technique, a 0.035-in guide wire is introduced through the needle and coiled within the pseudocyst (Figs. 2, 3). Following the needle insertion, the fistula created is dilated with either a 6 or 8 mm balloon over the guide wire which is coiled into the pseudocyst (Figs. 4, 5). The balloon is exchanged off of the guide wire and one or two 10-Fr double-pigtail stents or appropriately sized self-expandable metal stents are placed (Figs. 6, 7). Optionally, a nasocystic drain may be placed to flush the fluid collection.53 An alternative to the balloon dilation technique involves using a cystenterostome over the guide wire to enlarge the fistula using cautery.26 If the pancreatic duct is disrupted or a dominant stricture is present, the pancreatic duct should be stented.27

Gornals et al.45 reported median procedure time of 22 minutes (range, 10 to 30) in cases where NAVIX system was used, versus 40 minutes (range, 25 to 55) in cases with device exchanges. NAVIX device is a multifunction, exchange-free system that enables efficient pancreatic pseudocyst procedures due to the following features; 3.5 mm switchblade provides smooth access across the tissue layers, 8 mm anchor balloon secures the catheter position in the pseudocyst, aspiration port provides access for sampling, 10 mm balloon for tract dilation and two guidewire placement ports.46

Regarding maintenance period and removal criteria for stents, we recommend monthly surveillance with cross sectional imaging of the PFC. Once resolution is confirmed with restoration of pancreatic duct integrity, all stents should be ideally removed.

Wiersema54 in 1992 reported the first EUS-guided drainage of a PFC using an interventional (large-channel) EUS endoscope. Shortly after in 1995, Binmoeller and Soehendra55 reported an overall initial success rate with EUS-guided pseudocyst drainage of 78%. Giovannini et al.29 reported an 88.5% success rate (n=35) undergoing the same procedure for either pseudocyst drainage or pancreatic abscess drainage. Four of the patients in the Giovannini study went on to require surgery.29 A 2006 prospective study from Antillon et al.25 described 82% of patients undergoing EUS-guided drainage resulting in complete pseudocyst resolution, with only two out of thirty-three subjects experiencing major complications; and only one experiencing recurrence over 46 weeks. Krüger et al.31 described 36 patients who underwent EUS-guided drainage with a single-step needle wire device and 8.5 Fr stents. They found a resolution rate of 88% with a 12% recurrence rate over a 24-month period. PFC resolution was achieved by additional endoscopic cyst irrigation in 10 patients (30%); and might be related to the use of smaller diameter plastic stents. Hookey et al.21 studied 116 patients presenting with fluid collections (acute, pseudocysts, necrosis, and abscess) undergoing EUS-guided drainage. They employed EUS-guided transmural drainage technique in 32 patients, and combination of transpapillary and transmural drainage under EUS guidance in 19/41 patients. EUS was used in 44% (51/116) of all cases. The 90.6% of the EUS-guided transmural drainage cases were successful (29/32). The recurrence rate was 12.5% (4/32) with three complications (9.4%) reported. In this group, 12/32 patients (37.5%) had bulging fluid collections.21

A 2007 retrospective study by Lopes et al.33 of 51 patients undergoing EUS-guided transmural drainage of PFCs reported a 94% (48/51) success rate. There was a recurrence rate of 17.7% over 39 weeks. The placement of two stents decreased the complication rate for abscesses, while placement of a nasocystic drain did not.33

Kahaleh et al.32 reported a prospective study comparing 99 patients who underwent pseudocyst drainage using either conventional transmural drainage or EUS-guided drainage. Fifty-three patients who had a visible bulge and no obvious portal hypertension, underwent conventional drainage, while 46 patients underwent EUS-guided drainage. A comparable number of patients in each group underwent transpapillary stent placement for pancreatic duct disruption or stricture. Success rates at 1 month (93% vs. 94%) and 6 months (84% vs. 91%) were comparable. Complications occurred in 19% of EUS-guided drainage versus 18% of conventional transmural drainage, including three of bleeding, eight of infection, three of stent migration, and five of pneumoperitoneum. No significant differences in efficacy or safety were observed between the two techniques. The study concluded that the choice of technique is likely best predicted by individual patient presentation and local expertise, and recommended EUS for nonbulging collections and pseudocysts at risk for bleeding (i.e., intervening vessels or coagulopathy).32 Barthet et al.35 published a similar concept using EUS-guided transmural drainage performed on 28 patients (56%). The 90% of these patients achieved sustained response over a period of 12 months.35

A study from Varadarajulu et al.36 in 2008 compared the success rate between EUS and esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. In this prospective randomized trial, all patients in the EUS group had successful drainage while only 33% patients (5/15) in the conventional EGD group were successful.36 Major procedure-related bleeding occurred in two patients in the EGD group, one of whom died. Given these results, the study's authors concluded that EUS should be considered as a first-line therapy for pseudocyst drainage. However, a higher than average failure rate in the conventional group was noted when compared to a previously published study.26

Puri et al.56 reported the use of EUS-guided pseudocyst drainage technique involving the combined use of stents and nasocystic drainage. The authors prospectively studied 40 patients for EUS-guided symptomatic pseudocyst drainage, resistant to conservative treatment, and having no bulge seen on endoscopy. Successful drainage using EUS was achieved in all subjects. One patient required surgical resection of an infected pseudocyst because of bleeding inside the cyst. All patients had the double pigtail stents removed within 10 weeks.56

Zheng and Qin57 examined the efficacy and safety of 21 EUS-guided transgastric stentings of PFCs resulting specifically from trauma. They were able to successfully stent 90.5% (19/21) of these patients; the other two required surgery for pseudocyst drainage. Complications included two each of infected pseudocysts and stent obstructions. No PFC recurrences were seen over a 29-month period.57

In 2011, Varadarajulu et al.58 analyzed complications from EUS-guided PFC drainage in 148 patients. Two patients (1.3%) experienced perforation at the site of transmural stenting. Both of these occurred with the PFC located in the uncinate region of the pancreas; no perforations occurred elsewhere. One patient experienced bleeding, one had stent migration, while four experienced infections. The authors concluded that EUS-guided PFC drainage is a safe and effective procedure and also noted that a majority of the few complications seen were managed endoscopically.58

Will et al.59 published on 147 patients presenting with pseudocysts, abscesses, and necrosis. Within their follow-up period of 19.4 to 20.9 months, they documented success in 96.9% of patients with pseudocysts, 97.5% of those with pancreatic abscesses, and 94.1% of patients with necrosis. The group found an overall average recurrence rate of 15.4% between the three different diagnoses.59

Seewald et al.38 in a long-term follow-up study involving 80 patients reported 83% initial clinical success rate for transenteric drainage and/or necrosectomy in patients with PFCs. The long-term success rate was 72.5% (mean follow-up 21 months) due to the need for surgery in some patients either due to recurrence of fluid collections or failure of endoscopic treatment of pancreatic duct abnormalities. The study emphasized the need for EUS guidance for transenteric access of PFC to decrease the risk of bleeding. Additionally, addressing pancreatic duct abnormalities either endoscopically or surgically can prevent recurrence. Based on the literature review and our own clinical experience, we believe that most recurrences are related to the inability to resolve the underlying pancreatic duct issue, i.e., pancreatic duct leak or stricture. Either systematic ERCP for pancreatic duct exploration or imaging such as secretine MRI-magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography for all those patients is recommended. Unfortunately, to date, there are no large, randomized controlled studies comparing convention transmural and EUS-guided drainage in similar cohorts.

The type and number of appropriate stents following pancreatic pseudocyst drainage also remains equivocal. Most authors have conventionally used large plastic double pigtailed stents.20,32 Metal stents provide some theoretical advantages when compared to plastic as the radial force provided can tamponade bleeding vessels within the wall of the PFC. Additionally, wider diameter provides better drainage and possibly increases final success and reduced time to resolution. A study from Talreja et al.45 reported 18 patients who underwent PFC drainage using covered self-expandable metal stents (CSEMSs; VIABIL; Conmed, Utica, NY, USA). All but two underwent drainage with EUS-guidance. The 95% patients (17/18) responded successfully, with 78% of patients achieving complete resolution of their fluid collection.60 Another group has reported their experience with the use of metal stents for PFC drainage and facilitating necrosectomy.61

Fabbri et al.39 reported excellent success rates 17/20 (85%) with CSEMS in PFC cases with a mean follow-up of 610 days. The study reported stent migration and failure of endoscopic stent removal in one case each. Berzosa et al.41 also reported excellent success rates with CSEMS in seven patients with complete resolution in 9/10 PFCs with no complications.

Penn et al.42 reported used of double pigtail stent within the lumen of CSEMS to prevent migration of CSEMS in 20 patients. Migration of the CSEMS on follow-up endoscopy or imaging occurred in three patients; in two of these patients the CSEMS migrated from the pseudocyst into the gastric lumen, but the inner pigtail of the internal plastic stent remained within the collapsed pseudocyst cavity, thereby preventing complete migration. Initial success was achieved in 17/20 patients, with recurrence of PFC in three patients after stent removal. The authors performed a routine ERCP as a second procedure which is helpful in management of pancreatic duct disruptions but increases the risk of post-ERCP pancreatitis.42

Weilert et al.44 described use of the NAVIX one step access device for successful placement of CSEMS in 18 patients. The procedure was technically successful without any complications in all patients. In one patient, cystgastrostomy dilation resulted in dehiscence and was treated with repeat CSEMS placement. With this technique, the authors showed successful CSEMS placement without tract dilation for initial drainage for PFCs with indeterminate adherence to the luminal wall.

Based on the studies' conclusions, advantages of CSEMS include need of only a single stent for drainage, eliminating the need of accessing cyst cavity multiple times, decreased risk of occlusion, and decreased number of repeat procedures. However, stent migration is a potential limitation seen with CSEMS as well.39,42

Recently, a novel stent with dog bone shape has been developed in an attempt to better appose the PFC wall to the stomach wall and possibly improve drainage under EUS guidance. Itoi et al.40 first reported the use of such lumen-apposing stent (AXIOS; Xlumena Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) which is a fully covered, 10-mm diameter, nitinol, braided stent with bilateral anchor flanges designed to hold tissue in apposition. The AXIOS stents were successful in all cases without any complications, with none requiring repeat procedure during the 11.4 months median follow-up time. In one case, the stent migrated into the stomach without any consequence, while others were found to be patent at the time of removal.

Gornals et al.45 compared AXIOS with plastic double pigtail stents and found similar success rates. Authors reported higher complication rates and significantly greater number of stents used and mean procedure time with pigtail stents compared to AXIOS. One patient developed a tension pneumothorax secondary to transesophageal AXIOS placement. Due to the large size of the stent and anatomic structures involved, placement of AXIOS through the esophagus might be technically limited. The AXIOS stent thus far appears to be a remarkable development in the field of endoscopic PFC drainage. Lastly, large fully covered metal stents (esophageal stents) can offer a safer pathway to drain pancreatic necrosis. With further experience and development in stent designs, we are likely to see more efficient and easily deployable stents in the near future.

There is a growing body of research and literature report EUS-guided transmural PFC drainage as a safe and effective approach due to the continual improvement in techniques and instrumentation. A recent study by Mangiavillano et al.43 found single step EUS-guided drainage of PFC technically and clinically more successful than a two step technique. Also, the reported ease of use, technical success and safety of NAVIX device suggest a remarkable breakthrough in the technique.46 Studies like these are likely to standardize, simplify, and streamline EUS-guided drainage of PFC and help in its widespread adoption.

The application of EUS-guided PFC drainage increased dramatically over the last decade. Due to the extensive global use of EUS Guided PFC drainage, a growing number of studies are reporting on the safety and efficacy of evolving techniques. Many of these studies have examined the question of whether or not EUS-guidance is beneficial when compared to conventional transmural pancreatic pseudocyst drainage. Recent studies have also compared different techniques and stents. Yet, a large multicenter randomized controlled trial has not been reported that compares the two approaches to date. EUS-guidance offers clear benefits over conventional drainage such as defining the characteristics of a particular PFC, ruling out alternative diagnoses such as malignancy, and assessment for intervening vasculature. EUS guidance has also shown to be advantageous in accessing nonbulging PFCs, PFCs with indeterminate wall adherence or in high-risk clinical scenarios such as coagulopathy, intervening varices, or failed conventional transmural drainage. Accessibility to EUS guidance and availability of endoscopists trained in the modality are increasing. Continued advances in accessories such as NAVIX one step delivery system, use of CSEMS and AXIOS stents, expansion to more tertiary care centers, and further training of personnel will continue to make EUS techniques safer and more efficacious. Future large sample-sized comparative studies are also necessary for continued evaluation of these techniques.

References

1. Baron TH, Thaggard WG, Morgan DE, Stanley RJ. Endoscopic therapy for organized pancreatic necrosis. Gastroenterology. 1996; 111:755–764. PMID: 8780582.

2. Baillie J. Pancreatic pseudocysts (Part I). Gastrointest Endosc. 2004; 59:873–879. PMID: 15173808.

3. Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, et al. Six hundred fifty consecutive pancreaticoduodenectomies in the 1990s: pathology, complications, and outcomes. Ann Surg. 1997; 226:248–257. PMID: 9339931.

4. Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, Chamlou R, et al. Endoscopic therapy for main pancreatic-duct rupture after Silastic-ring vertical gastroplasty. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 62:143–151. PMID: 15990839.

5. Klöppel G. Pseudocysts and other non-neoplastic cysts of the pancreas. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2000; 17:7–15. PMID: 10721803.

6. Bradley EL 3rd. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993; 128:586–590. PMID: 8489394.

7. Baron TH, Harewood GC, Morgan DE, Yates MR. Outcome differences after endoscopic drainage of pancreatic necrosis, acute pancreatic pseudocysts, and chronic pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 56:7–17. PMID: 12085029.

8. Baron TH, Morgan DE. The diagnosis and management of fluid collections associated with pancreatitis. Am J Med. 1997; 102:555–563. PMID: 9217671.

9. Yeo CJ, Bastidas JA, Lynch-Nyhan A, Fishman EK, Zinner MJ, Cameron JL. The natural history of pancreatic pseudocysts documented by computed tomography. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1990; 170:411–417. PMID: 2326721.

10. Bradley EL, Clements JL Jr, Gonzalez AC. The natural history of pancreatic pseudocysts: a unified concept of management. Am J Surg. 1979; 137:135–141. PMID: 758840.

11. Gouyon B, Lévy P, Ruszniewski P, et al. Predictive factors in the outcome of pseudocysts complicating alcoholic chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 1997; 41:821–825. PMID: 9462217.

12. Warshaw AL, Rattner DW. Timing of surgical drainage for pancreatic pseudocyst. Clinical and chemical criteria. Ann Surg. 1985; 202:720–724. PMID: 4073984.

13. Bradley EL 3rd. A fifteen year experience with open drainage for infected pancreatic necrosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1993; 177:215–222. PMID: 8356492.

14. Boerma D, van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Internal drainage of infected pancreatic pseudocysts: safe or sorry? Dig Surg. 1999; 16:501–505. PMID: 10805550.

15. vanSonnenberg E, Wittich GR, Casola G, et al. Percutaneous drainage of infected and noninfected pancreatic pseudocysts: experience in 101 cases. Radiology. 1989; 170(3 Pt 1):757–761. PMID: 2644662.

16. Ahearne PM, Baillie JM, Cotton PB, Baker ME, Meyers WC, Pappas TN. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)-based algorithm for the management of pancreatic pseudocysts. Am J Surg. 1992; 163:111–115. PMID: 1733357.

17. Adams DB, Harvey TS, Anderson MC. Percutaneous catheter drainage of infected pancreatic and peripancreatic fluid collections. Arch Surg. 1990; 125:1554–1557. PMID: 2244807.

18. Neff R. Pancreatic pseudocysts and fluid collections: percutaneous approaches. Surg Clin North Am. 2001; 81:399–403. PMID: 11392426.

19. Binmoeller KF, Seifert H, Walter A, Soehendra N. Transpapillary and transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995; 42:219–224. PMID: 7498686.

20. Cahen D, Rauws E, Fockens P, Weverling G, Huibregtse K, Bruno M. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts: long-term outcome and procedural factors associated with safe and successful treatment. Endoscopy. 2005; 37:977–983. PMID: 16189770.

21. Hookey LC, Debroux S, Delhaye M, Arvanitakis M, Le Moine O, Devière J. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections in 116 patients: a comparison of etiologies, drainage techniques, and outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 63:635–643. PMID: 16564865.

22. Delhaye M, Matos C, Devière J. Endoscopic management of chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2003; 13:717–742. PMID: 14986795.

23. Giovannini M. EUS-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 9:32–38.

24. Howell DA, Holbrook RF, Bosco JJ, Muggia RA, Biber BP. Endoscopic needle localization of pancreatic pseudocysts before transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993; 39:693–698. PMID: 8224695.

25. Antillon MR, Shah RJ, Stiegmann G, Chen YK. Single-step EUS-guided transmural drainage of simple and complicated pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 63:797–803. PMID: 16650541.

26. Sanchez Cortes E, Maalak A, Le Moine O, et al. Endoscopic cystenterostomy of nonbulging pancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 56:380–386. PMID: 12196776.

27. Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, Bali MA, et al. Pancreatic-fluid collections: a randomized controlled trial regarding stent removal after endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 65:609–619. PMID: 17324413.

28. Baron TH. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008; 12:369–372. PMID: 17906903.

29. Giovannini M, Pesenti C, Rolland AL, Moutardier V, Delpero JR. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts or pancreatic abscesses using a therapeutic echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2001; 33:473–477. PMID: 11437038.

30. Azar RR, Oh YS, Janec EM, Early DS, Jonnalagadda SS, Edmundowicz SA. Wire-guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage by using a modified needle knife and therapeutic echoendoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 63:688–692. PMID: 16564874.

31. Krüger M, Schneider AS, Manns MP, Meier PN. Endoscopic management of pancreatic pseudocysts or abscesses after an EUS-guided 1-step procedure for initial access. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 63:409–416. PMID: 16500388.

32. Kahaleh M, Shami VM, Conaway MR, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst: a prospective comparison with conventional endoscopic drainage. Endoscopy. 2006; 38:355–359. PMID: 16680634.

33. Lopes CV, Pesenti C, Bories E, Caillol F, Giovannini M. Endoscopic-ultrasound-guided endoscopic transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts and abscesses. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007; 42:524–529. PMID: 17454865.

34. Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM, Tamhane A, Eloubeidi MA, Blakely J, Canon CL. Role of EUS in drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections not amenable for endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 66:1107–1119. PMID: 17892874.

35. Barthet M, Lamblin G, Gasmi M, Vitton V, Desjeux A, Grimaud JC. Clinical usefulness of a treatment algorithm for pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:245–252. PMID: 18226686.

36. Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Tamhane A, Drelichman ER, Wilcox CM. Prospective randomized trial comparing EUS and EGD for transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 68:1102–1111. PMID: 18640677.

37. Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, van Brunschot S, et al. Endoscopic transgastric vs surgical necrosectomy for infected necrotizing pancreatitis: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012; 307:1053–1061. PMID: 22416101.

38. Seewald S, Ang TL, Richter H, et al. Long-term results after endoscopic drainage and necrosectomy of symptomatic pancreatic fluid collections. Dig Endosc. 2012; 24:36–41. PMID: 22211410.

39. Fabbri C, Luigiano C, Cennamo V, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transmural drainage of infected pancreatic fluid collections with placement of covered self-expanding metal stents: a case series. Endoscopy. 2012; 44:429–433. PMID: 22382852.

40. Itoi T, Binmoeller KF, Shah J, et al. Clinical evaluation of a novel lumenapposing metal stent for endosonography-guided pancreatic pseudocyst and gallbladder drainage (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012; 75:870–876. PMID: 22301347.

41. Berzosa M, Maheshwari S, Patel KK, Shaib YH. Single-step endoscopic ultrasonography-guided drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections with a single self-expandable metal stent and standard linear echoendoscope. Endoscopy. 2012; 44:543–547. PMID: 22407382.

42. Penn DE, Draganov PV, Wagh MS, Forsmark CE, Gupte AR, Chauhan SS. Prospective evaluation of the use of fully covered self-expanding metal stents for EUS-guided transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012; 76:679–684. PMID: 22732874.

43. Mangiavillano B, Arcidiacono PG, Masci E, et al. Single-step versus two-step endo-ultrasonography-guided drainage of pancreatic pseudocyst. J Dig Dis. 2012; 13:47–53. PMID: 22188916.

44. Weilert F, Binmoeller KF, Shah JN, Bhat YM, Kane S. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections with indeterminate adherence using temporary covered metal stents. Endoscopy. 2012; 44:780–783. PMID: 22791588.

45. Gornals JB, De la Serna-Higuera C, Sánchez-Yague A, Loras C, Sánchez-Cantos AM, Pérez-Miranda M. Endosonography-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections with a novel lumen-apposing stent. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27:1428–1434. PMID: 23232994.

46. Binmoeller KF, Weilert F, Shah JN, Bhat YM, Kane S. Endosonography-guided transmural drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts using an exchange-free access device: initial clinical experience. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27:1835–1839. PMID: 23299130.

47. Andrén-Sandberg A, Dervenis C. Pancreatic pseudocysts in the 21st century. Part II: natural history. JOP. 2004; 5:64–70. PMID: 15007187.

48. Jacobson BC, Baron TH, Adler DG, et al. ASGE guideline: the role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and the management of cystic lesions and inflammatory fluid collections of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 61:363–370. PMID: 15758904.

49. Varadarajulu S, Bang JY, Phadnis MA, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic transmural drainage of peripancreatic fluid collections: outcomes and predictors of treatment success in 211 consecutive patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011; 15:2080–2088. PMID: 21786063.

50. Seifert H, Dietrich C, Schmitt T, Caspary W, Wehrmann T. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided one-step transmural drainage of cystic abdominal lesions with a large-channel echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2000; 32:255–259. PMID: 10718392.

51. Seifert H, Faust D, Schmitt T, Dietrich C, Caspary W, Wehrmann T. Transmural drainage of cystic peripancreatic lesions with a new large-channel echo endoscope. Endoscopy. 2001; 33:1022–1026. PMID: 11740644.

52. Giovannini M, Bernardini D, Seitz JF. Cystogastrotomy entirely performed under endosonography guidance for pancreatic pseudocyst: results in six patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998; 48:200–203. PMID: 9717789.

53. Baron TH. Endoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts, abscesses and organized (walled-off) necrosis. In : Baron TH, Kozarek RA, Carr-Locke DL, editors. ERCP. Philadelphia: Saunders/Elsevier;2008. p. 475–491.

54. Wiersema MJ. Endosonography-guided cystoduodenostomy with a therapeutic ultrasound endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996; 44:614–617. PMID: 8934175.

55. Binmoeller KF, Soehendra N. Endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1995; 5:805–816. PMID: 8535629.

56. Puri R, Mishra SR, Thandassery RB, Sud R, Eloubeidi MA. Outcome and complications of endoscopic ultrasound guided pancreatic pseudocyst drainage using combined endoprosthesis and naso-cystic drain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 27:722–727. PMID: 22313377.

57. Zheng M, Qin M. Endoscopic ultrasound guided transgastric stenting for the treatment of traumatic pancreatic pseudocyst. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011; 58:1106–1109. PMID: 21937358.

58. Varadarajulu S, Christein JD, Wilcox CM. Frequency of complications during EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collections in 148 consecutive patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011; 26:1504–1508. PMID: 21575060.

59. Will U, Wanzar C, Gerlach R, Meyer F. Interventional ultrasound-guided procedures in pancreatic pseudocysts, abscesses and infected necroses: treatment algorithm in a large single-center study. Ultraschall Med. 2011; 32:176–183. PMID: 21259182.

60. Talreja JP, Shami VM, Ku J, Morris TD, Ellen K, Kahaleh M. Transenteric drainage of pancreatic-fluid collections with fully covered self-expanding metallic stents (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 68:1199–1203. PMID: 19028232.

61. Antillon MR, Bechtold ML, Bartalos CR, Marshall JB. Transgastric endoscopic necrosectomy with temporary metallic esophageal stent placement for the treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 69:178–180. PMID: 18582877.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download