Abstract

Colorectal endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) still remains a technically difficult procedure. The maintenance of tissue tension and good submucosal exposure during dissection is one of the most important factors for an effective and safe dissection. Although various traction methods have been developed, traction by gravity is one of the most useful method for colorectal ESD. Traction using adjunctive devices can thus be reserved for extremely difficult cases or for endoscopists in their learning periods for colorectal ESD.

As a result of the development of endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), the en bloc resection of larger gastrointestinal neoplasms can be performed successfully. However, ESD still has many limitations, including its technical difficulty, long procedure times, and risks of perforation and bleeding. Because the colorectal wall is much thinner than the gastric wall, the risk of perforation is considerably greater in colorectal ESD than in gastric ESD. The perforation rates associated with colorectal ESD were approximately 10% in several reports1,2 although this rate has been decreasing as the skills, materials, and devices for ESD are improved.

Adequate tissue tension and good visibility of the tissue to be dissected are very important for effective and safe dissections, and they can be achieved by traction of the tissue to be dissected. In this article, we will discuss various techniques for achieving tractions during ESD and their advantages and disadvantages.

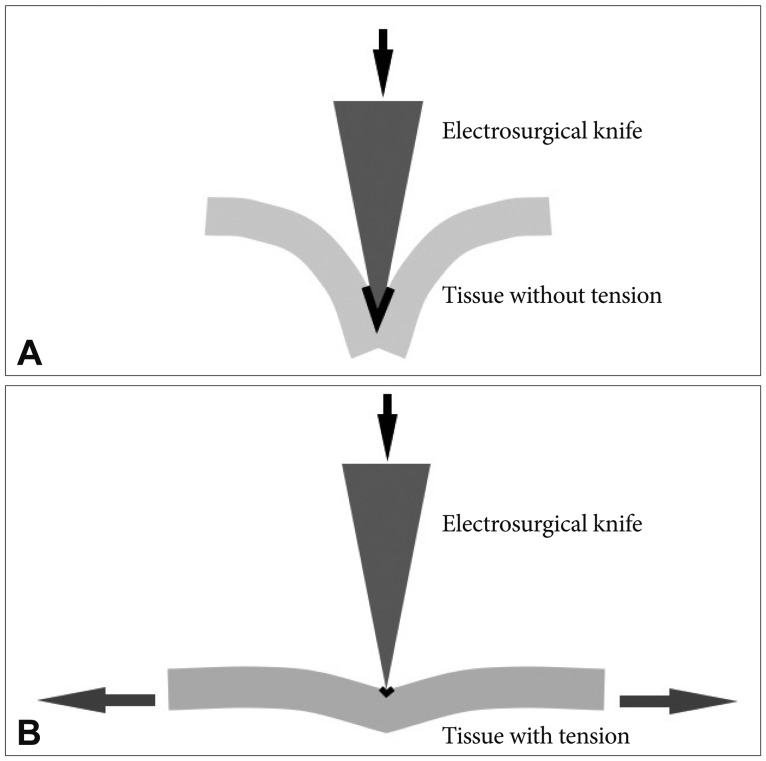

Traction decreases the contact area between the tissue and the electrosurgical knife by increasing the tissue tension (Fig. 1). The current density increases as the contact area decreases, which enables a more effective cut.

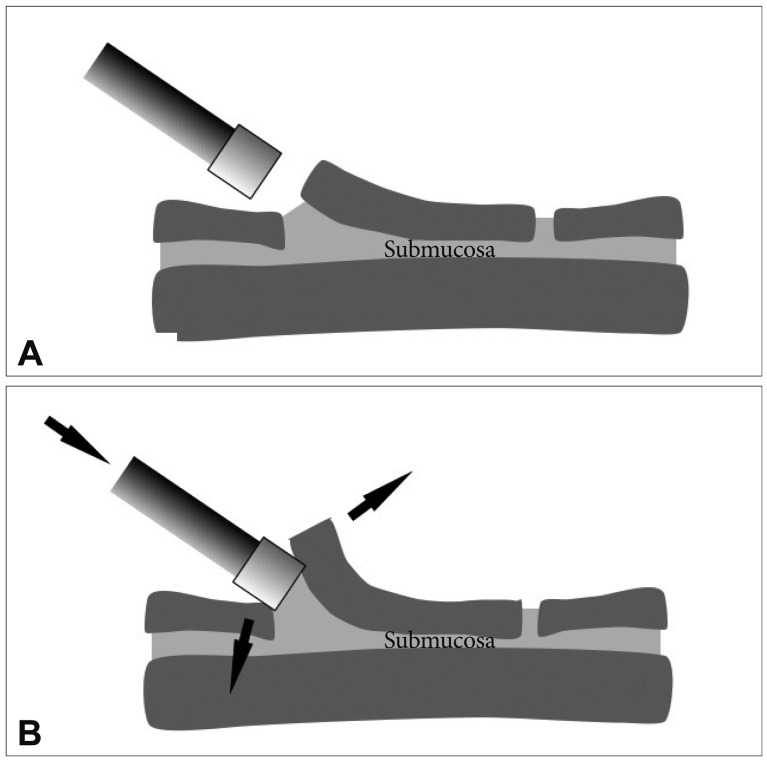

Secondly, traction can provide better submucosal exposure (Fig. 2). The precise dissection of the submucosal layer is the most important step for preventing perforation, and the electrosurgical knife should always aim for the submucosal layer during dissection. Therefore, improved submucosal exposure through traction is helpful for more effective and safer dissections.

Surgeons are usually aided by the hands of assistants or by various instruments to maintain the tissue tension and visibility of the tissue to be dissected. In ESD, achieving good traction is not easy because only an electrosurgical knife can be passed through the single working channel. Therefore, ESD can be compared to one-handed surgery.

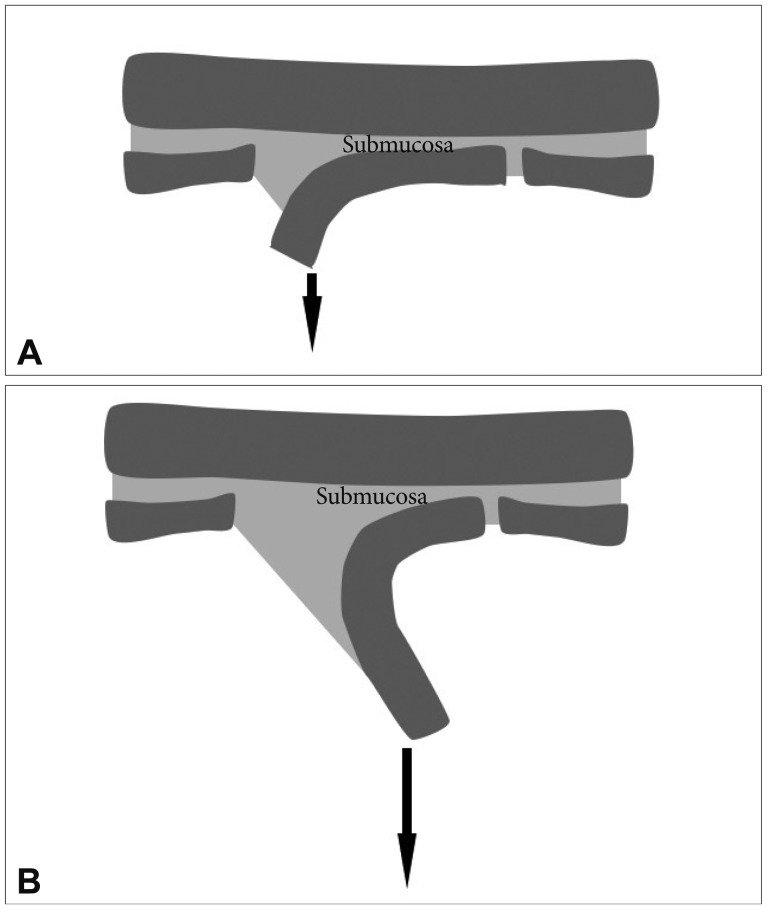

The transparent distal attachment is a simple device that provides tissue tension and submucosal exposure. By inserting the transparent hood in between the flap and its base, more submucosa can be exposed and better tissue tension can be achieved (Fig .3). This technique can also keep the tip of the endoscope at a suitable distance from the tissue such that the phenomenon of red-out can be avoided.

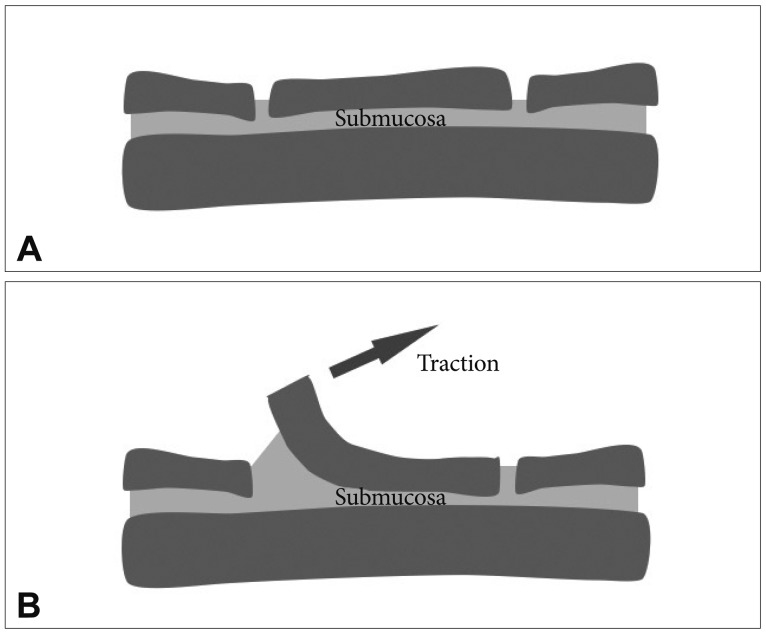

Traction force can be simply achieved through gravity.3 The direction of the traction force can be controlled by changing the position of the patient. While the patient's position during gastric ESD is limited to left lateral decubitus, various positions, even including the prone position are allowed during colorectal ESD. The optimal position is estimated by the location of fluid in the lumen. Locating fluid on the opposite side of the lesion, which can cause the flap to be strained to the side of the luminal center, is usually preferred. However, submucosal exposure may not be insufficient in the early stages of the dissection because the flap has not yet been sufficiently prepared. As the dissection progresses, the weight of the flap increases, and thus the traction force increases due to gravity (Fig. 4). Insufficient submucosal exposure at an early stage can be complemented by the submucosal injection of longlasting materials, such as glycerol or hyaluronic acid4 and the use of a transparent hood.

The traction force by gravity can be strengthened by applying a small weight.5 This sinker system consists of a 1-g weight, a clip, and a connecting nylon thread. By attaching the clip to the mucosal edge after a circumferential incision, the traction force due to weight allows a better submucosal exposure.

Various other adjunctive methods have been developed to control and strengthen the traction force. A thread and a clip can also be used for traction. The clip is attached to the tip of the flap and the end of the thread is pulled though a thin tube by an assistant during the colorectal ESD. Pushing the endoscope and pulling the thread can together lift the flap.6 Various methods using clips and a thread has also been attempted in esophageal or gastric ESD.7-12

The traction force can be prepared internally using elastic materials. A rubber band between a clip attached to the tip of the flap and another clip attached to normal mucosa can provide a continuous traction force during colorectal ESD.13 The method can also be applied to gastric lesions,13-15 and a thin spring can replace a rubber band.16,17

The use of an extracorporeal electromagnet was attempted in gastric ESD.18 In this trial, a large extracorporeal electromagnet was used to attract a small magnet that was attached to the mucosal edge for traction.

External forceps can be used for traction in rectal ESD.19 After a pair of bendable forceps is introduced with the help of other grasping forceps, and fixed to the mucosal edge, the bendable forceps are bent or pulled to elevate the lesion. Forceps to elevate the mucosa can be introduced through a channel within a specialized transparent hood.20 Similar methods have also been used for esophageal21 or gastric ESD.22,23

One of the advantages of traction by gravity is that it does not require any additional devices. Moreover, the direction of traction force can be easily controlled by changing the patient's position. As mentioned above, traction force by gravity may not be sufficient at early stages of dissection, in which case the traction force can be complemented by a transparent hood and submucosal injection.

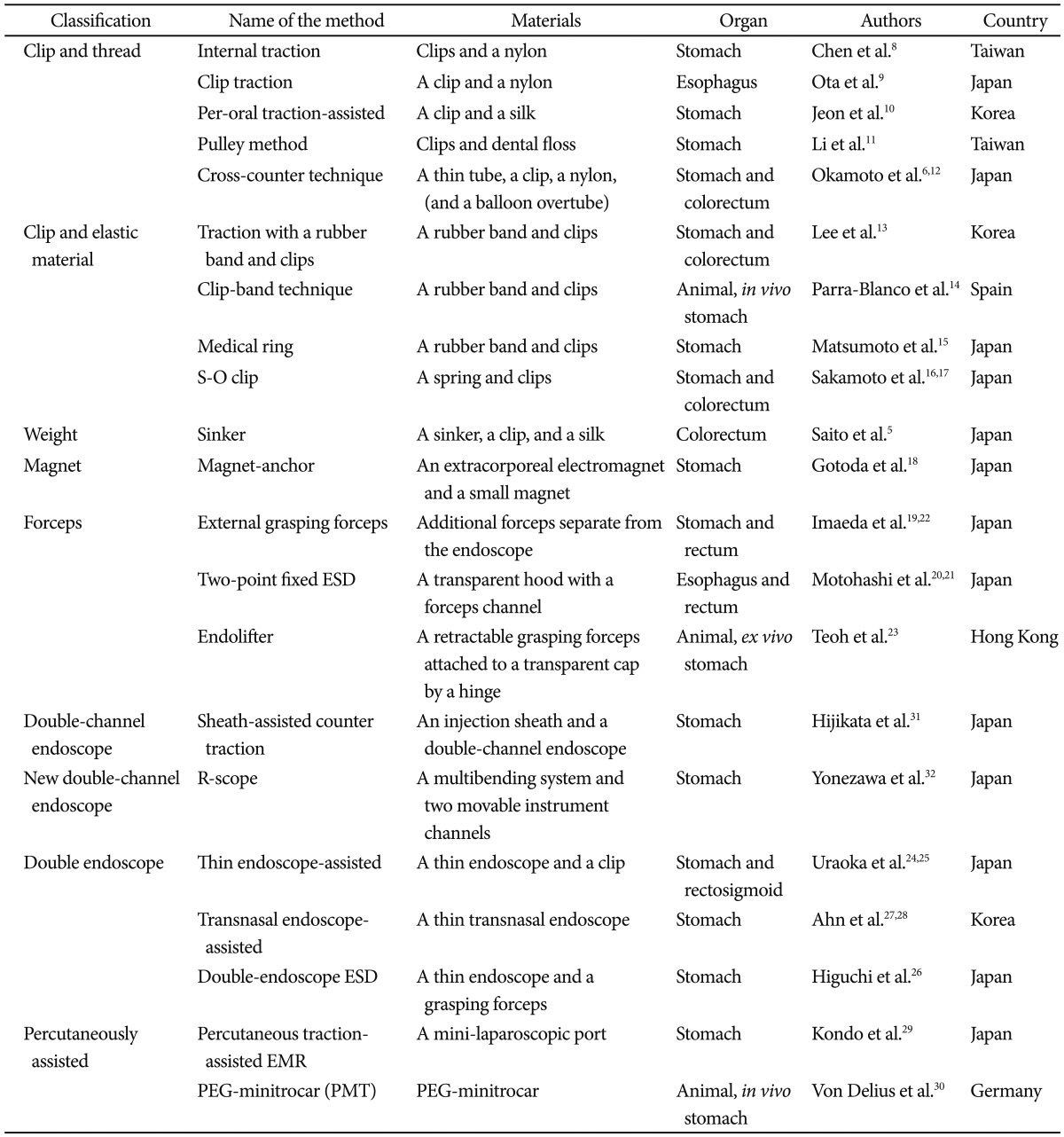

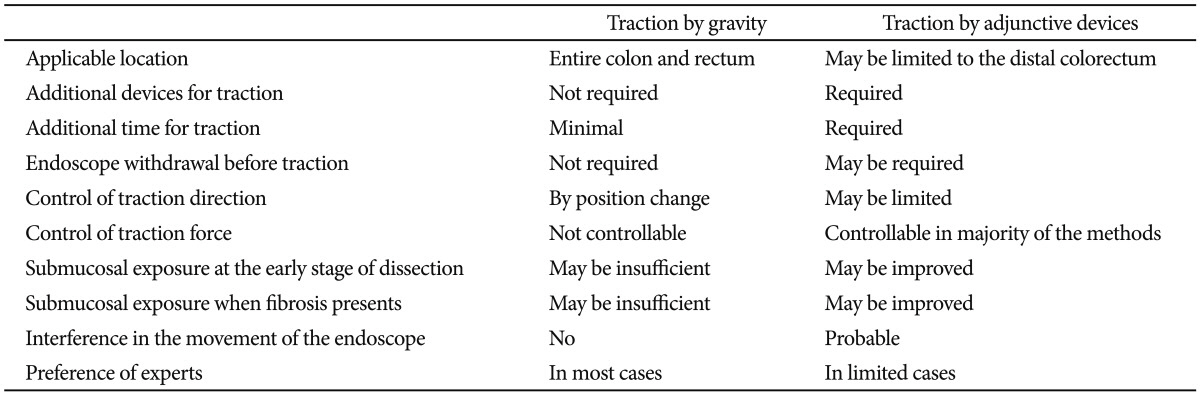

In contrast, traction by adjunctive devices can create a good traction force from the early stages. It may be more useful when submucosal exposure is insufficient because of fibrosis. However, traction by adjunctive devices requires additional materials and time. Specialized, expensive, or even huge devices may be required.18,32 Some methods are more invasive than conventional ESD,29,30 and the endoscope should occasionally be withdrawn and reinserted to provide traction.5-12,19,22 The movement of the primary endoscope may be hindered by the second endoscope to maintain traction.24-27 Moreover, majority of the methods has not been tested in colorectal ESD (Table 1).

The advantages and disadvantages of traction by gravity versus traction by adjunctive devices are listed in Table 2.

Colorectal ESD remains a technically difficult procedure. The maintenance of tissue tension and good submucosal exposure during dissection is one of the most important factors for an effective and safe dissection. Various traction methods using adjunctive devices have been developed and may be useful for difficult cases. However, they have many limitations and require additional effort.

Traction by gravity is not only a simple method, but also a useful method for most colorectal ESD cases and is preferred by majority of experts. Traction using adjunctive devices can thus be reserved for extremely difficult cases or for endoscopists in their learning periods of colorectal ESD.

References

1. Taku K, Sano Y, Fu KI, et al. Iatrogenic perforation associated with therapeutic colonoscopy: a multicenter study in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 22:1409–1414. PMID: 17593224.

2. Kim YJ, Kim ES, Cho KB, et al. Comparison of clinical outcomes among different endoscopic resection methods for treating colorectal neoplasia. Dig Dis Sci. 2013; 58:1727–1736. PMID: 23385636.

3. Oyama T. Counter traction makes endoscopic submucosal dissection easier. Clin Endosc. 2012; 45:375–378. PMID: 23251884.

4. Fujishiro M, Yahagi N, Nakamura M, et al. Successful outcomes of a novel endoscopic treatment for GI tumors: endoscopic submucosal dissection with a mixture of high-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid, glycerin, and sugar. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 63:243–249. PMID: 16427929.

5. Saito Y, Emura F, Matsuda T, et al. A new sinker-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for colorectal cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 62:297–301. PMID: 16046999.

6. Okamoto K, Muguruma N, Kitamura S, Kimura T, Takayama T. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for large colorectal tumors using a crosscounter technique and a novel large-diameter balloon overtube. Dig Endosc. 2012; 24(Suppl 1):96–99. PMID: 22533761.

7. Oyama T, Y K, Shimaya S, et al. Endoscopic submucosal resection using a hook knife (hooking EMR). Stomach Intest. 2002; 37:1155–1161.

8. Chen PJ, Chu HC, Chang WK, Hsieh TY, Chao YC. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with internal traction for early gastric cancer (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:128–132. PMID: 18054010.

9. Ota M, Nakamura T, Hayashi K, et al. Usefulness of clip traction in the early phase of esophageal endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2012; 24:315–318. PMID: 22925282.

10. Jeon WJ, You IY, Chae HB, Park SM, Youn SJ. A new technique for gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: peroral traction-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 69:29–33. PMID: 19111686.

11. Li CH, Chen PJ, Chu HC, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with the pulley method for early-stage gastric cancer (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 73:163–167. PMID: 21030018.

12. Okamoto K, Okamura S, Muguruma N, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer using a cross-counter technique. Surg Endosc. 2012; 26:3676–3681. PMID: 22692462.

13. Lee BI, Kim BW, Choi H, et al. Traction with using a rubber band and clips for effective endoscopic submucosal dissection. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 36:341–348.

14. Parra-Blanco A, Nicolas D, Arnau MR, Gimeno-Garcia AZ, Rodrigo L, Quintero E. Gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection assisted by a new traction method: the clip-band technique. A feasibility study in a porcine model (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 74:1137–1141. PMID: 22032320.

15. Matsumoto K, Nagahara A, Ueyama H, et al. Development and clinical usability of a new traction device "medical ring" for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. Epub 2013 Mar 23. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00464-013-2887-6.

16. Sakamoto N, Osada T, Shibuya T, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of large colorectal tumors by using a novel spring-action S-O clip for traction (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 69:1370–1374. PMID: 19403131.

17. Sakamoto N, Osada T, Shibuya T, et al. The facilitation of a new traction device (S-O clip) assisting endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial colorectal neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2008; 40(Suppl 2):E94–E95. PMID: 19085712.

18. Gotoda T, Oda I, Tamakawa K, Ueda H, Kobayashi T, Kakizoe T. Prospective clinical trial of magnetic-anchor-guided endoscopic submucosal dissection for large early gastric cancer (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 69:10–15. PMID: 18599053.

19. Imaeda H, Hosoe N, Ida Y, et al. Novel technique of endoscopic submucosal dissection by using external forceps for early rectal cancer (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012; 75:1253–1257. PMID: 22624814.

20. Motohashi O. Two-point fixed endoscopic submucosal dissection in rectal tumor (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 74:1132–1136. PMID: 21944316.

21. Motohashi O, Nishimura K, Nakayama N, Takagi S, Yanagida N. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (two-point fixed ESD) for early esophageal cancer. Dig Endosc. 2009; 21:176–179. PMID: 19691765.

22. Imaeda H, Hosoe N, Ida Y, et al. Novel technique of endoscopic submucosal dissection using an external grasping forceps for superficial gastric neoplasia. Dig Endosc. 2009; 21:122–127. PMID: 19691787.

23. Teoh AY, Chiu PW, Hon SF, Mak TW, Ng EK, Lau JY. Ex vivo comparative study using the Endolifter® as a traction device for enhancing submucosal visualization during endoscopic submucosal dissection. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27:1422–1427. PMID: 23093235.

24. Uraoka T, Ishikawa S, Kato J, et al. Advantages of using thin endoscopeassisted endoscopic submucosal dissection technique for large colorectal tumors. Dig Endosc. 2010; 22:186–191. PMID: 20642607.

25. Uraoka T, Kato J, Ishikawa S, et al. Thin endoscope-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for large colorectal tumors (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 66:836–839. PMID: 17905031.

26. Higuchi K, Tanabe S, Azuma M, et al. Double-endoscope endoscopic submucosal dissection for the treatment of early gastric cancer accompanied by an ulcer scar (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2013; 78:266–273. PMID: 23472995.

27. Ahn JY, Choi KD, Lee JH, et al. Is transnasal endoscope-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neoplasm useful in training beginners? A prospective randomized trial. Surg Endosc. 2013; 27:1158–1165. PMID: 23093232.

28. Ahn JY, Choi KD, Choi JY, et al. Transnasal endoscope-assisted endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric adenoma and early gastric cancer in the pyloric area: a case series. Endoscopy. 2011; 43:233–235. PMID: 21165828.

29. Kondo H, Gotoda T, Ono H, et al. Percutaneous traction-assisted EMR by using an insulation-tipped electrosurgical knife for early stage gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004; 59:284–288. PMID: 14745409.

30. von Delius S, Karagianni A, von Weyhern CH, et al. Percutaneously assisted endoscopic surgery using a new PEG-minitrocar for advanced endoscopic submucosal dissection (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 68:365–369. PMID: 18561928.

31. Hijikata Y, Ogasawara N, Sasaki M, et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection with sheath-assisted counter traction for early gastric cancers. Dig Endosc. 2010; 22:124–128. PMID: 20447206.

32. Yonezawa J, Kaise M, Sumiyama K, Goda K, Arakawa H, Tajiri H. A novel double-channel therapeutic endoscope ("R-scope") facilitates endoscopic submucosal dissection of superficial gastric neoplasms. Endoscopy. 2006; 38:1011–1015. PMID: 17058166.

Fig. 1

Association between tissue tension and contact area. (A) Before applying tension. (B) After applying tension. Decreased contact area from increased tissue tension makes for an effective dissection.

Fig. 3

Role of the distal transparent hood. (A) Insufficient submucosal exposure can be improved (B) by gently pushing the hood into the submucosal layer.

Fig. 4

The traction force by gravity during dissection. (A) Early stage of dissection. (B) After the dissection has progressed.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download