Abstract

Intestinal metaplasia of the stomach is a common metaplastic lesion associated with chronic gastritis and mucosal atrophy. However, squamous metaplasia is a comparatively rare condition. On endoscopy, squamous metaplasia is usually observed as a whitish mucosal lesion in the lesser curvature of the cardiac region of the stomach. When Lugol's iodine solution is applied, the lesion stains brown in the same way as normal esophageal mucosa. We report a case of 79-year-old man with a whitish flat lesion in the lesser curvature of the cardiac region on surveillance endoscopy after endoscopic treatment of gastric adenoma. The endoscopic biopsy showed stratified squamous epithelial mucosa.

Squamous metaplasia of the stomach is a relatively unusual clinical condition that has been occasionally described. It can occur during healing of inflammatory conditions,1 tuberculosis,2 or even with an aberrant pancreatic tissue.3 So far, only several cases have been reported referring the endoscopic findings of gastric squamous metaplasia.4,5 And in all cases, the metaplastic lesions were observed as pale area that had a look of esophageal mucosa. Herein we report a case of gastric squamous metaplasia which was found incidentally on surveillance endoscopy after endoscopic treatment for gastric adenoma.

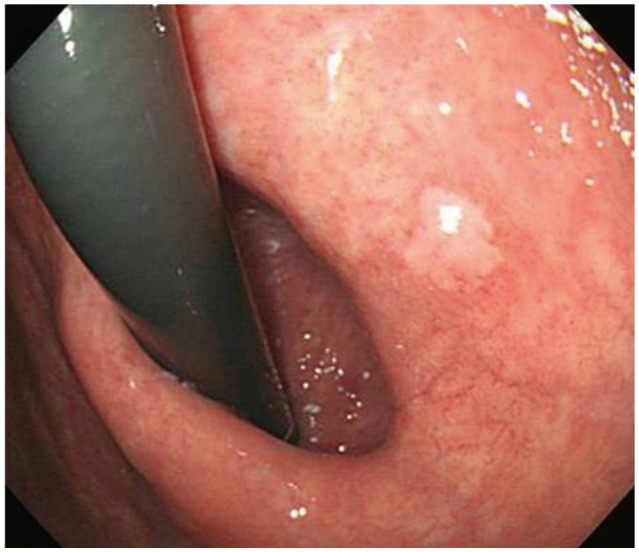

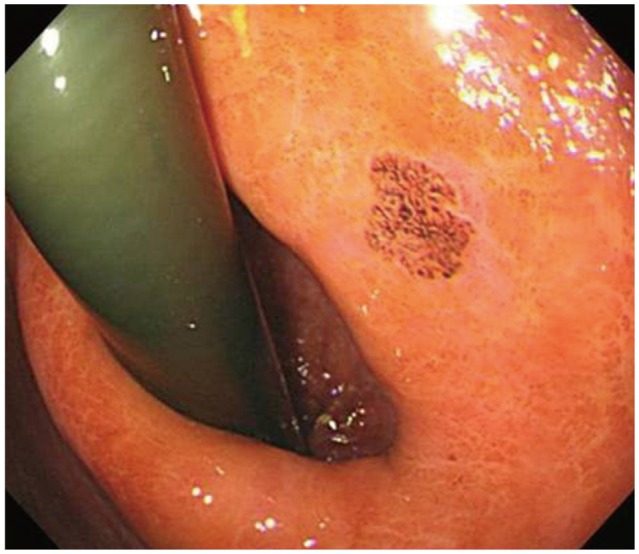

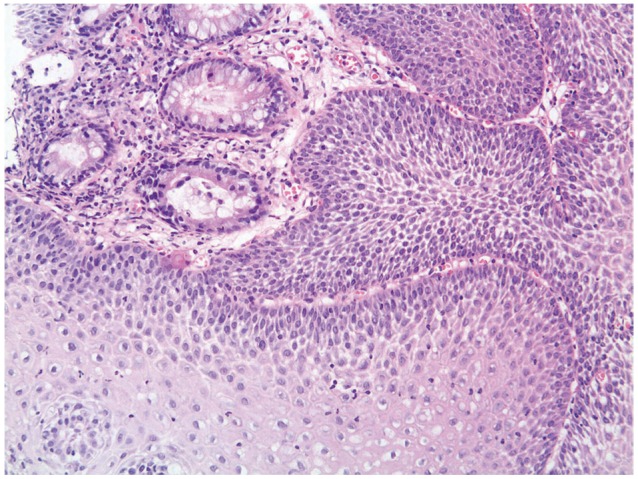

A 79-year-old man had undergone an endoscopic submucosal dissection for a gastric adenoma with low grade dysplasia 3 years ago. The final histological diagnosis was low grade dysplasia, equal to the preresectional diagnosis. Then he underwent surveillance endoscopy annually. There was no abnormal finding on first and second follow-ups. However, at the third visit, a conventional endoscopy revealed a whitish flat lesion in the lesser curvature of cardiac region of the stomach (Fig. 1), the lesion which was away from the scar area which occurred after the endoscopic resection of the adenoma. In addition, the whitish lesion was distinctly away from the normal esophageal mucosa, but its appearance looked like normal esophageal mucosa. Therefore, chromoendoscopy using Lugol's iodine solution was performed to make sure whether the lesion was squamous mucosa or not. When Lugol's iodine solution was applied, the lesion was stained brown in the same way as normal esophageal mucosa (Fig. 2). The endoscopic biopsy from the whitish lesion revealed stratified squamous epithelial mucosa (Fig. 3). The final diagnosis was gastric squamous metaplasia.

Gastric squamous metaplasia is a somewhat rare clinical entity. Normal gastric columnar epithelium generally appears pink and normal esophageal squamous epithelium appears white on endoscopy. Therefore, if the squamous metaplasia was present in the stomach, it would appear as a whitish lesion. In addition, after spraying Lugol's iodine solution, the lesion would be stained brown like normal esophageal mucosa. Actually in a previous report,4 the squamous metaplasia appeared as a whitish patch in the lesser curvature of the cardiac region of the stomach and it was stained positively with Lugol's iodine solution as our present case.

Squamous cell metaplasia may affect the lesser curvature of the stomach preferentially, if it does not spread into the entire stomach.5 Therefore, squamous metaplasia should be included as differential diagnosis when a whitish lesion of irregular shape is seen in the cardia during endoscopic examination.

Lugol's iodine staining interacts with carbohydrate containing structures inside the cell and color of the mucosa changes changes into brown color. Lugol's iodine spraying causes dark brown staining of nonkeratinized squamous epithelium, while decrease or absence of dye uptake is seen in conditions, such as esophagitis, squamous cell dysplasia, or carcinoma, which result from depletion of glycogen in squamous cells.6 Therefore, the practical use of this staining is to detect abnormal squamous mucosa including high grade dysplasia and early squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus.7 On the contrary, this staining can be adopted to detect squamous epithelium in the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, if the whitish lesion is observed during endoscopy, an iodide spraying would be helpful for the diagnosis of squamous metaplasia.

The pathogenesis of squamous metaplasia in the stomach remains obscure.8 However, it has been thought that it is associated with chronic inflammation resulting from environmental stimuli. In our case, the pathogenesis of squamous metaplasia was uncertain, but we presumed that some inflammatory responses might have affected the metaplastic change. The squamous epithelial cells develop as descendants of multipotent stem cells.9 It seems that squamous metaplasia occurs accidentally, motivated by repeated detriment on gastric mucosa. Although it is unknown whether gastric squamous metaplasia leads to squamous carcinoma or not, it could sometimes give rise to squamous cell carcinoma of the stomach in some reports.1,5,10 Accordingly, endoscopic surveillance is essential for patients with gastric squamous metaplasia.

In summary, if a whitish lesion is observed in the lesser curvature of the cardiac region of the stomach and if it appears a normal esophageal mucosa, application of Lugol's iodine solution is helpful in distinguishing squamous metaplasia from other whitish mucosal lesions such as gastric adenoma or early gastric cancer.

References

1. Vaughan WP, Straus FH 2nd, Paloyan D. Squamous carcinoma of the stomach after luetic linitis plastica. Gastroenterology. 1977; 72(5 Pt 1):945–948. PMID: 191328.

2. Watson GW, Flint ER, Stewart MJ. Hyperplastic tuberculosis of the stomach causing hour-glass deformity, with complete squamous metaplasia of the upper loculus. Br J Surg. 1936; 24:333–340.

3. Yamagiwa H, Yosimura H, Nishii M, Moriyama S. Squamous metaplasia of the gastric mucosa associated with an aberrant pancreas. Gan No Rinsho. 1987; 33:1929–1932. PMID: 3430744.

4. Takeda H, Nagashima R, Goto T, Shibata Y, Shinzawa H, Takahashi T. Endoscopic observation of squamous metaplasia of the stomach: a report of two cases. Endoscopy. 2000; 32:651–653. PMID: 10935797.

5. Boswell JT, Helwig EB. Squamous cell carcinoma and adenoacanthoma of the stomach. A clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 1965; 18:181–192. PMID: 14254074.

6. Fennerty MB, Sampliner RE, McGee DL, Hixson LJ, Garewal HS. Intestinal metaplasia of the stomach: identification by a selective mucosal staining technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992; 38:696–698. PMID: 1282115.

7. Rerknimitr R. Practical use of digital chromoendoscopy for GI tract diseases including GERD. Thai J Gastroenterol. 2009; 9:147–159.

8. Parks RE. Squamous neoplasms of the stomach. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1967; 101:447–449.

9. Wood DA. Adenoacanthoma of the pyloric end of the stomach. Arch Pathol. 1943; 36:177–189.

10. Oono Y, Fu K, Nagahisa E, et al. Primary gastric squamous cell carcinoma in situ originating from gastric squamous metaplasia. Endoscopy. 2010; 42(Suppl 2):E290–E291. PMID: 21113875.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download