Abstract

Background/Aims

Endoscopic management of upper gastrointestinal obstruction is safe and feasible. However, its technical and clinical success rate is about 90%, which is primarily due to inability to pass a guide-wire through the stricture. The aim of this study was to evaluate the usefulness of an ultrathin endoscope for correct placement of guide wire to avoid technical failure in upper gastrointestinal obstruction.

Methods

Retrospective assessment of ultrathin endoscope to traverse the stenosis of the upper gastrointestinal tract in technically difficult cases was performed. Technical and clinical success rates and immediate complications were analyzed.

Results

Nine cases were included in this study (eight cases of stent insertion and one case of balloon dilatation). Technical success was achieved in all of the patients (100%) and oral feeding was feasible in all of the cases (100%). Immediate complications, such as migration, perforation, and hemorrhage, did not develop in any of the cases.

The need for endoscopic management of gastrointestinal obstruction has been increased due to recent increase in detection rate of gastrointestinal cancer and increased survival of patients with improved therapeutic strategies. Self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) insertion and balloon dilatation are widely accepted management methods for gastrointestinal obstruction. However, endoscopic management is not always feasible due to tight or tortuous stenosis of the obstructed area and insufficient visualization of the anal side of the lesion. Other factors, such as the location of the lesion, causes of the lesion including extraluminal causes, and the degree of the stenosis, affect the clinical outcome. The technical success rate of SEMS is reported to be 89% and the clinical success rate is about 87%.1

Ultrathin endoscope have been used mainly for pediatric patients, transnasal endoscopy or feeding tube placements.2,3 However, the usefulness of this ultrathin endoscope for the management of gastrointestinal obstruction has rarely been reported.4 The aim of this study was to evaluate the usefulness of an ultrathin endoscope for correct placement of guide wire to avoid technical failure in upper gastrointestinal obstruction.

Retrospective review of patients who underwent SEMS insertion or balloon dilatation due to benign or malignant obstruction of the upper gastrointestinal tract between July 2008 and June 2011 was performed. This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Technical difficulty was defined as follows: first, failure of guide wire insertion through the stenosis over 30 minutes with conventional endoscope despite using at least two endoscopic devices. Second, failure of guide wire insertion despite changing the patients' positions several times to approach to the stenotic lesion.

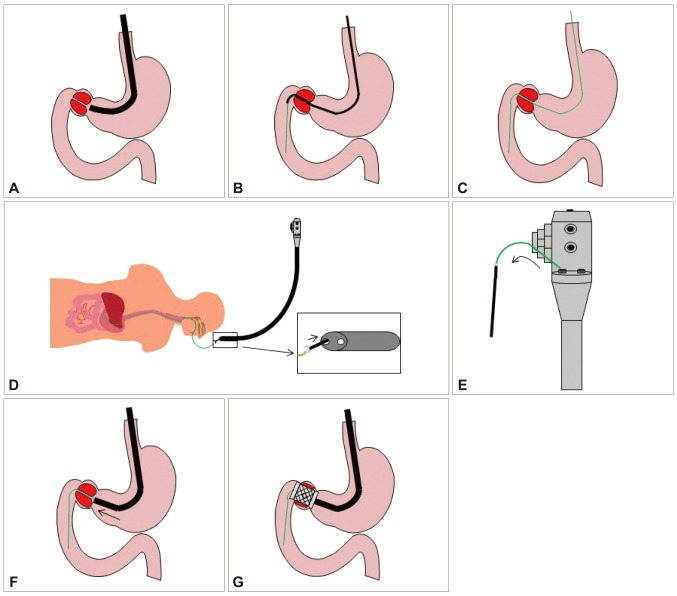

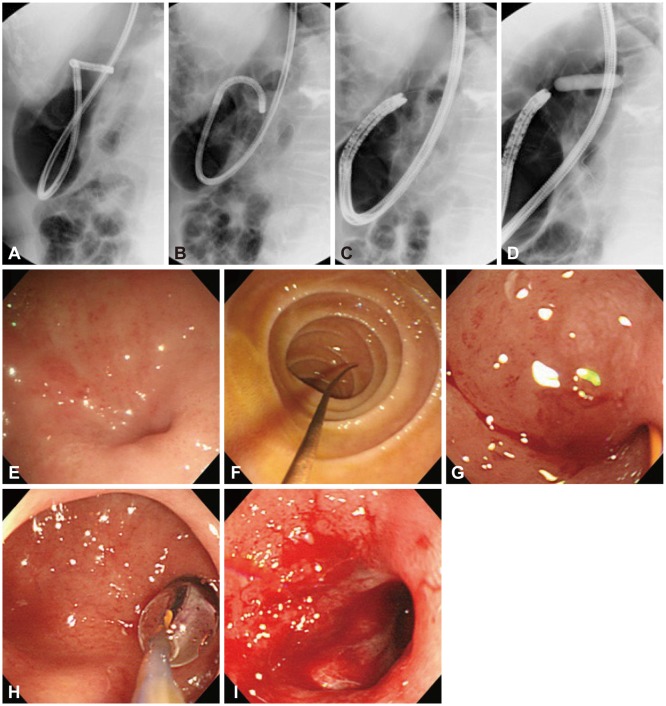

When guide wire insertion failed with conventional endoscope, ultrathin endoscope (GIF XP260; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted and traversed the stenosis or approached directly in front of the orifice of the stenotic lesion. The outer diameter of ultrathin endoscope is 6.5 mm and the inner diameter of its working channel is 2.0 mm. Then, the guide wire (MET-35-480; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) was inserted through the working channel of the ultrathin endoscope and the ultrathin endoscope was removed completely, leaving the guide wire in place. After insertion of the alligator forceps through the working channel of the two channel endoscope (GIF 2T240; Olympus), the opposite side of the guide wire was grabbed with alligator forceps and retrieved through the working channel. Then the two channel endoscope was inserted into the patient along with the guide wire to approach the stenotic legion. SEMS or balloon was inserted over the guide wire through the working channel and the rest of the procedures was performed by a through the scope (TTS) manner (Fig. 1). An example of this procedure is presented in Fig. 2.

Technical success was defined as completion of the procedure; in cases of SEMS, adequate placement and satisfactory expansion of SEMS was defined as success; in a case of balloon dilatation, dilatation of the stenotic lesion which enables passage of the two channel endoscope was defined as success.

Clinical success was defined as improvement of obstructive symptoms such as vomiting, dysphagia, and odynophagia with the possibility of oral feeding.

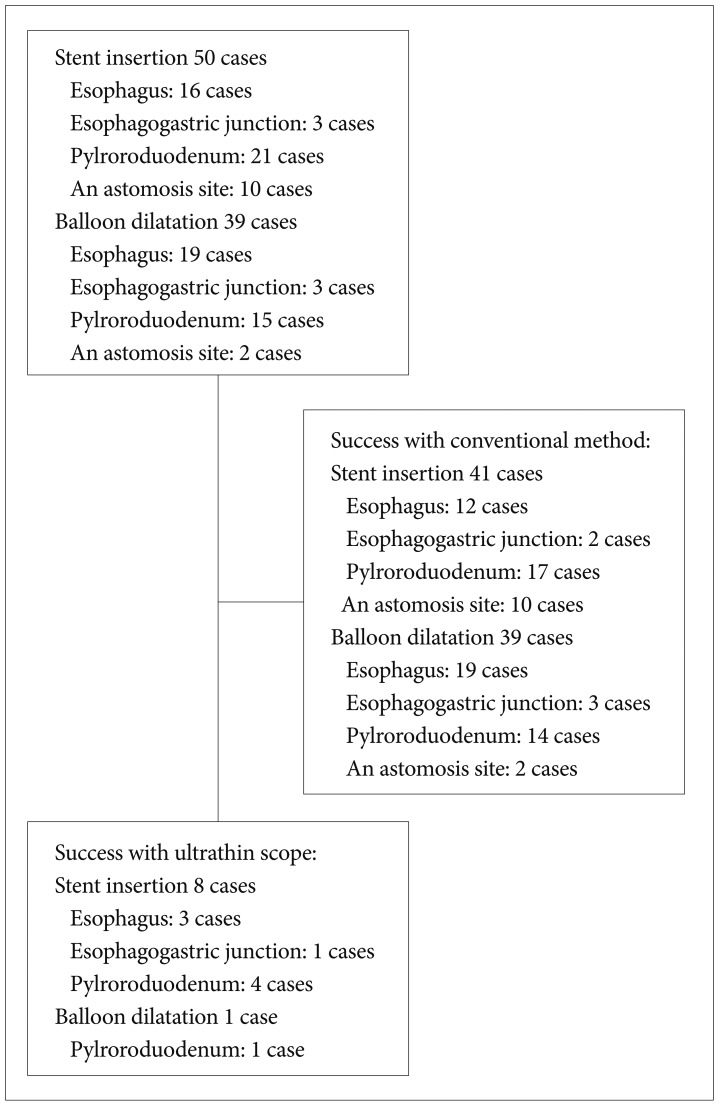

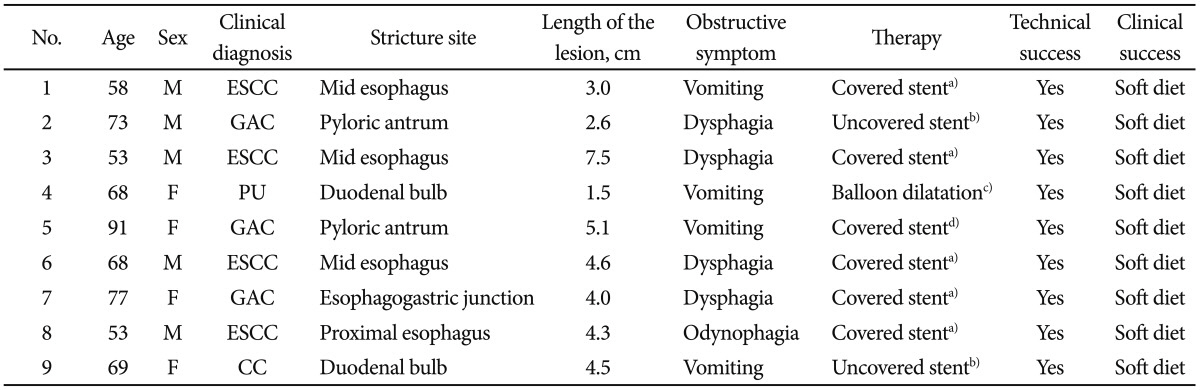

During the study period, stent insertion was performed in 50 patients and balloon dilatation was performed in 39 patients (Fig. 3). A total of nine patients were included in this study (five male and four female). Mean age of the patients was 67.8 years old. Among the nine patients, four patients had esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, three patients had advanced gastric adenocarcinoma involving the pylorus, one patient had duodenal bulb obstruction due to peptic ulcer, and one patient had duodenal obstruction due to invasion of cholangiocarcinoma. Characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1.

Technical success was obtained in all nine patients (Table 1). Obstructing symptoms, such as vomiting, dysphagia and odynophagia, disappeared after the procedure. Oral feeding was possible in all of the patients after the procedures (Table 1). There was no immediate procedure-related complication such as migration of the SEMS, transfusion requiring hemorrhage or gastrointestinal perforation.

Correct placement of the guide wire beyond the stricture is one of the most important steps for proper management of gastrointestinal obstruction. In our current study, we demonstrated an efficient technique for the management of upper gastrointestinal obstruction by using an ultrathin endoscope. The ultrathin endoscope could pass through the stenosis more easily than a conventional endoscope, thus making it possible to traverse the guide wire. Furthermore, it enabled us to visualize the anal side of the lesion and to measure the length of the stenosis. We could also assess the characteristics of the stenosis.

However, most of the TTS devices cannot pass through the forceps channel of the ultrathin endoscope, which forced us to change to an endoscope with a larger forceps channel or handle the TTS device in an over the wire manner. Unfortunately due to twisting of the delivery system, it is difficult to handle the TTS devices in such an over the wire manner. To exchange the ultrathin endoscope for the endoscope with a larger forceps channel, we need to get the guide wire tip through the larger bore channel of a two channel endoscope. But when we retrieve the guide wire from the tip of two channel endoscope without any devices, it usually goes into the suction channel and we cannot get the tip of guide wire from the forceps channel. So we grabbed the tip of the guide wire with an alligator forceps after insertion of the alligator forceps through the large bore channel of the two channel endoscope.

With conventional methods, technical and clinical success rate was known to be about 90%.5 However, with our ultrathin scope-assisted method, the success rate was about 100% even in technically difficult situations. Due to limited number of cases and retrospective design of the study, this should be clarified in large scaled randomized controlled trials in the future.

Efforts for proper placement of the guide wire with side-viewing endoscope and sphincterotome-assisted techniques have been reported.6,7 However, these techniques were performed only in large bowel obstruction and were not tried in upper gastrointestinal obstruction. Furthermore, these techniques might increase the injury of the obstructed area and might result in drastic situations when failed. So we attempted with an ultrathin endoscope to avoid such severe complications. The first report of using the ultrathin endoscope to pass through esophageal strictures and for nasogastric tube placement was presented in 1998.8 Many kinds of procedures were enabled with this ultrathin endoscope in technically difficult situations.9-11 But ultrathin endoscope is not always successful in gastrointestinal obstruction.12

Previous studies using ultrathin endoscope were mainly performed in left sided colorectal obstructions with lesions less than 20 cm from the anus.4,13 In the colon, the ultrathin endoscope bends easily and loses its strength in the distal tip, thus limiting its use to lesions close to the anus. We analyzed this procedure in upper gastrointestinal obstruction only and oral feeding was feasible in all cases after the procedure, which was considered as a clinical success. We performed the procedure under fluoroscopy to avoid other complications, though there is no evidence that fluoroscopy-guided procedure is safer than procedure without fluoroscopy. Our results suggest that ultrathin endoscope is more useful and easier to use in upper gastrointestinal obstruction than colonic obstruction.

There are several limitations in using an ultrathin endoscope. First, the lenses are more prone to being obscured and aspiration channels are more easily clogged due to gastric contents because its size is smaller than that of conventional endoscopes. Also, there is the nuance of changing the ultrathin endoscope to a two channel endoscope after the guide wire is passed through the stenosis site. This may lead to increased risks of guide wire removal and increased procedure time. Despite these limitations, it should be considered in selected cases when it is difficult to pass the guide wire through the stenosis.

The major drawback of our current study is that it is a retrospective study, with inherent limitations of such a study design. There was no control group to compare the success rate or complication rate. Although, we tried to define technical difficulty specifically, indication for using an ultrathin endoscope may still be vague. Also, the high number of success rate may be due to the small number of patients and its retrospective design.

In conclusion, our study suggests that ultrathin endoscopeassisted technique is potentially safe and useful when upper gastrointestinal obstruction is not amenable to conventional endoscope. Further prospective studies are anticipated to confirm the safety and usefulness of this technique.

References

1. Dormann A, Meisner S, Verin N, Wenk Lang A. Self-expanding metal stents for gastroduodenal malignancies: systematic review of their clinical effectiveness. Endoscopy. 2004; 36:543–550. PMID: 15202052.

2. Dumortier J, Ponchon T, Scoazec JY, et al. Prospective evaluation of transnasal esophagogastroduodenoscopy: feasibility and study on performance and tolerance. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999; 49(3 Pt 1):285–291. PMID: 10049409.

3. Lustberg AM, Darwin PE. A pilot study of transnasal percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002; 97:1273–1274. PMID: 12014751.

4. García-Cano J. Use of an ultrathin gastroscope to allow endoscopic insertion of enteral wallstents without fluoroscopic monitoring. Dig Dis Sci. 2006; 51:1231–1235. PMID: 16944017.

5. Vlavianos P, Zabron A. Clinical outcomes, quality of life, advantages and disadvantages of metal stent placement in the upper gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2012; 6:27–32. PMID: 22228029.

6. Cennamo V, Fuccio L, Laterza L, et al. Side-viewing endoscope for colonic self-expandable metal stenting in patients with malignant colonic obstruction. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 21:585–586. PMID: 19282771.

7. Vázquez-Iglesias JL, Gonzalez-Conde B, Vázquez-Millán MA, Estévez-Prieto E, Alonso-Aguirre P. Self-expandable stents in malignant colonic obstruction: insertion assisted with a sphincterotome in technically difficult cases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 62:436–437. PMID: 16111965.

8. Mulcahy HE, Fairclough PD. Ultrathin endoscopy in the assessment and treatment of upper and lower gastrointestinal tract strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998; 48:618–620. PMID: 9852453.

9. Itoi T, Ishii K, Sofuni A, et al. Ultrathin endoscope-assisted ERCP for inaccessible peridiverticular papilla by a single-balloon enteroscope in a patient with Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Dig Endosc. 2010; 22:334–336. PMID: 21175491.

10. Krishna SG, McElreath DP, Rego RF. Direct pancreatoscopy with an ultrathin forward-viewing endoscope in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm of the pancreas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009; 7:e75–e76. PMID: 19683071.

11. Yan SL, Chen CH, Yeh YH, Yueh SK. Successful biliary stenting and sphincterotomy using an ultrathin forward-viewing endoscope. Endoscopy. 2009; 41(Suppl 2):E59–E60. PMID: 19319781.

12. Aydinli M, Koruk I, Dag MS, Savas MC, Kadayifci A. Ultrathin endoscopy for gastrointestinal strictures. Dig Endosc. 2012; 24:150–153. PMID: 22507087.

13. García-Cano J, González Martín JA, Redondo-Cerezo E, et al. Treatment of malignant colorectal obstruction by means of endoscopic insertion of self-expandable metallic stents. An Med Interna. 2003; 20:515–520. PMID: 14585037.

Fig. 1

Schema of the ultrathin endoscope-assisted method. (A) The stenotic lesion was approached with a conventional scope. (B) When guide wire insertion failed with the conventional scope, the ultrathin endoscope passed through the stenotic lesion and the guide wire was inserted into the forceps channel. (C) The guide wire was placed in the stenotic lesion and the ultrathin endoscope was retrieved completely. (D) The tip of the guide wire was grabbed with an alligator forceps which was already inserted into the large bore channel of the two channel endoscope. (E) The guide wire was retrieved through the large bore channel of the two channel endoscope. (F) The two channel endoscope was inserted into the patient and approached to the stenotic lesion. (G) The self-expandable metallic stent was inserted and expanded in the stenotic lesion.

Fig. 2

A case of ultrathin endoscope-assisted method. (A) The ultrathin endoscope approaching the orifice of the stenotic lesion is shown by fluoroscopy. (B) The guide wire insertion through the ultrathin endoscope is shown by fluoroscopy. (C) The ultrathin endoscope exchanged for the two channel endoscope is shown by fluoroscopy. (D) The balloon dilating the stenotic lesion is shown by fluoroscopy. (E) The orifice of the stenotic lesion is found at the duodenal bulb by ultrathin endoscope. (F) The guide wire is placed at the second portion of the duodenum after passing through the stenotic lesion by the ultrathin endoscope. (G) The guide wire is placed in the stenotic lesion by the two channel endoscope. (H) The balloon is dilating the stenotic lesion in a through the scope manner. (I) After dilatation, the orifice of the stenotic lesion is expanded.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download