Abstract

Crohn disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that affects the entire gastrointestinal tract but is most frequently localized to the large and small bowel. Small bowel endoscopy helps with the differential diagnosis of CD in suspected CD patients. Early diagnosis of CD is preferable for suspected CD conditions to improve chronic inflammatory infiltrates, fibrosis. Small bowel endoscopy can help with the early detection of active disease, thus leading to early therapy before the onset of clinical symptoms of established CD. Some patients with CD have mucosal inflammatory changes not in the terminal ileum but in the proximal small bowel. Conventional ileocolonoscopy cannot detect ileal involvement proximal to the terminal ileum. Small bowel endoscopy, however, can be useful for evaluating these small bowel involvements in patients with CD. Small bowel endoscopy by endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD) enables the treatment of small bowel strictures in patients with CD. However, many practical issues still need to be addressed, such as endoscopic findings for early detection of CD, application compared with other imaging modalities, determination of the appropriate interval for endoscopic surveillance of small bowel lesions in patients with CD, and long-term prognosis after EBD.

Crohn disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by intestinal ulceration. CD affects the entire gastrointestinal tract but is most frequently localized to the large and small bowel. It is difficult to evaluate subtle mucosal changes in the small bowel in patients with CD by radiographic examination. Push enteroscopy was the standard modality for evaluating subtle mucosal changes in the small bowel in patients with CD; however, this technique only allows limited endoscopic access for diagnosis and treatment. New modalities for examining the small bowel, such as capsule endoscopy (CE), balloon-assisted endoscopy (BAE), and spiral endoscopy, have been used in the present decade. Although the usefulness of small bowel endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of IBD has not yet been definitely established, it is expected to be used as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality in some cases of IBD.

CE was introduced as a novel method for direct exploration of the mucosa of the small bowel.1 It has been shown to be a useful diagnostic modality in small bowel disorders. The advantages of CE are that it is noninvasive, requires no sedation, and can be performed easily even in outpatients; however, CE cannot be used to clean the mucosa or take biopsy specimens, and the movement of the endoscope in the intestine cannot be controlled. A novel paddling-based locomotive capsule endoscope was developed, which showed fast and stable movement in the colon of an anesthetized pig.2 When this new capsule endoscope becomes available for use in humans, the disadvantages of CE will gradually decrease.

Capsule endoscope retention is a major complication in CE. It is defined as the presence of the capsule endoscope in the digestive tract for a minimum of 2 weeks or more. The overall rate of capsule retention in patients is reported to be approximately 1% to 2.5%.3-9 In a previous Korean study, Kim and Jang10 reported that capsule retention occurred in 2.5% of the total patients (32/1,291), and that 11 of the 32 (34.4%) patients with capsule retention eventually passed the capsule. A higher rate of capsule retention (5.6% to 13%) has been reported in patients with CD than in control patients.11,12 Once CE is retained, endoscopic or surgical removal is often necessary. Many patients with capsule retention are asymptomatic and do not require emergency intervention. However, some case reports have shown that acute symptomatic small bowel obstruction requiring emergency intervention can occur because of intestinal perforation due to capsule retention.13-17

Several case reports have shown that a balloon-assisted endoscope can reach the deep small bowel and can be utilized to retrieve the retained capsule in patients not requiring emergency intervention.9,18-21 However, the retained capsule cannot always be removed using BAE. In particular, patients with CD may have several strictures or severe adhesion, which are often located at sites distal to the small intestine. Even if some strictures can be dilated using endoscopic balloon dilation (EBD) via a retrograde approach, it may not always be possible to dilate a more proximal stenosis responsible for the retention.

To avoid capsule retention in patients with CD, CE should be performed after patency of the small intestine is established using a patency capsule. In Japan, as specified by the Japanese public health insurance system, CE cannot be performed in patients with established CD without first establishing the patency of the small intestine by using a patency capsule.

The Agile patency capsule, which is a self-dissolving capsule of the same size as the PillCam SB2 capsule (Given Imaging, Yoqneam, Israel), has been used to detect intestinal strictures in patients with suspected strictures. This Agile patency capsule is composed of lactose with 5% barium that surrounds a small inner radio frequency identification tag. The body is coated with an impermeable membrane. Two timer plugs at each end seal the capsule's body. There is an opening in each wax plug, which allows penetration by intestinal fluids. The wax plugs control the disintegration time of the capsule, and begin to erode after 30 hours if the capsule is retained in the intestine, by allowing penetration of body fluids into the capsule and dissolving the material in the body. If the patency capsule is egested intact, the patency of the small bowel is considered to be established. Any changes in its original dimensions, such as a disintegrating soft body or an empty shell and tag, show that patency could not be established. The patency capsule used in Japan is a modified version of the Agile patency capsule stated above, and it contains no radio frequency identification tag to avoid the risk of obstructive symptoms due to the tag becoming lodged in the strictures.

Double-balloon endoscopy (DBE), which involves the use of two balloons (one is attached to the tip of the endoscope and the other to the distal end of the accompanying overtube), and single-balloon endoscopy (SBE), which is based on principles similar to those of DBE, were developed as new techniques for visualization and intervention in the small bowel.22 These two types of endoscopies collectively constitute BAE. Oshitani et al.23 reported the experience of BAE in 40 Japanese patients with CD. The utility of DBE was compared to that of small-bowel follow-through (SBFT) examination in detecting longitudinal ulcers, erosion, and strictures in 30 patients. The SBFT examination failed to detect not only faint mucosal changes such as erosions in 100% (nine of nine patients) of the patients but also longitudinal ulcers in 22% of the patients (four of 18 patients).

Unlike CE, BAE has the advantage of enabling histological examination of the deep small bowel via biopsy specimen collection. De Ridder et al.24 reported the diagnostic value of SBE in children with suspected IBD and those with confirmed CD with possible small bowel activity. In their study, endoscopic lesions in the small bowel were observed in 13 of 20 consecutive patients, and in 12 of these 13 (92%) patients, inflammation was confirmed by histopathological examination.

Diagnostic DBE was accompanied by complication in less than 1% of cases.25 The specific complication rate of BAE in patients with IBD is not clear. When BAE is performed in patients with IBD, particular attention should be paid to not inflate the overtube balloon on the deep ulcerative mucosa in order to avoid intestinal perforation. Although active CD lesions tend to develop on the mesenteric side of the bowel wall, it is relatively difficult to examine the mesenteric side by using BAE because during the endoscopic insertion, the ileum twists toward the mesenteric side, and the view of the scope tends to skew toward the antimesenteric side. Therefore, endoscopists need to be careful to avoid missing active deep ulcers even in the presence of longitudinal ulcers.

Spiral endoscopy is the new per-oral endoscopic procedure for visualizing the small bowel.26 Recently, a per-anal procedure has become available for clinical application. In this procedure, an overtube with a raised helix tip is used to pleat the small bowel. The coupled endoscope and overtube are advanced into the small bowel by using gentle clockwise rotation of the overtube. Several studies have reported that spiral endoscopy is a safe and effective method for diagnosis and treatment in the small bowel.26-32 However, no studies have compared the usefulness of spiral endoscopy with that of other modalities in patients with CD or have clarified the reason why spiral endoscopy may be relatively traumatic to the mucosa in patients with CD.

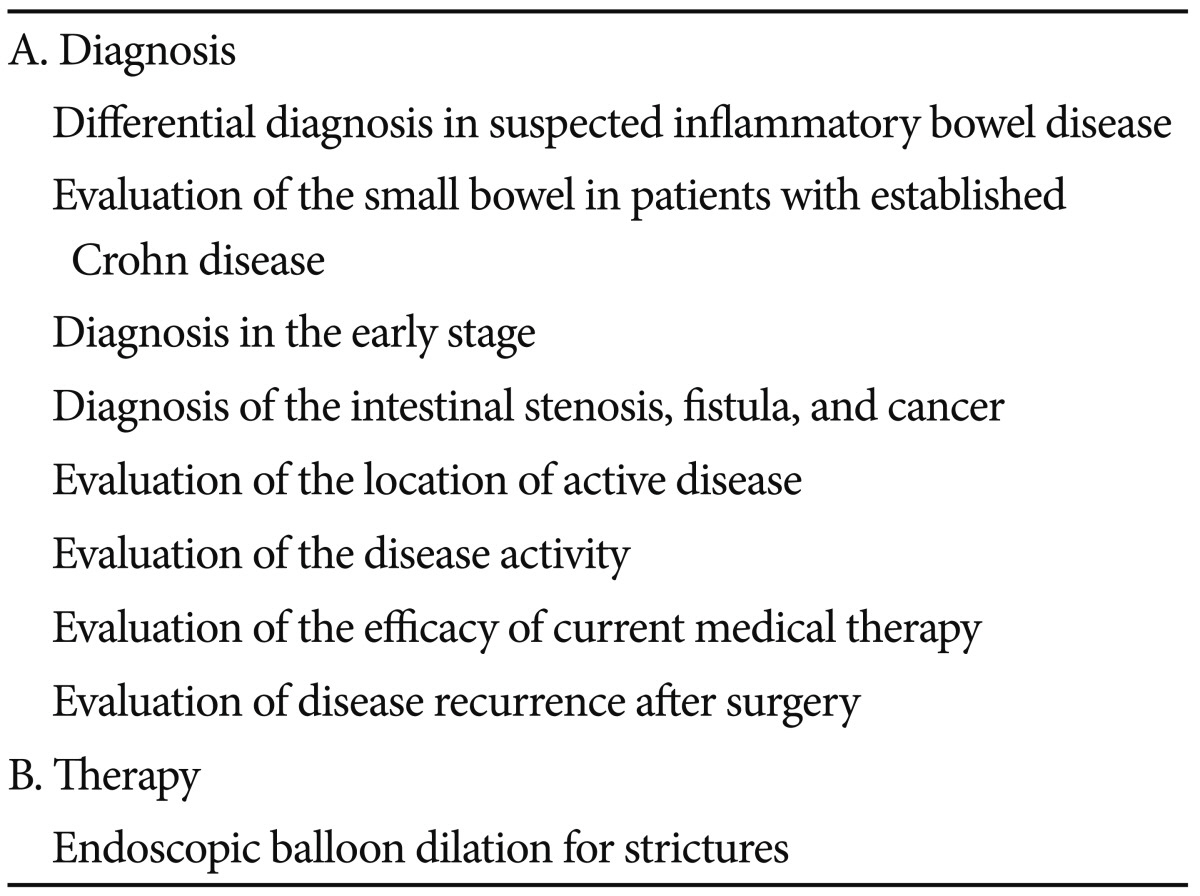

The applications of small bowel endoscopy in IBD are shown in Table 1.

In patients with colitis with an unclassified type of IBD (IBDU), or suspected CD based on medical history and physical examination, evaluation of the small bowel may be useful to revise a diagnosis. Mehdizadeh et al.33 reported the diagnostic yield of CE in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) or IBDU. Of 120 patients with UC or IBDU, 19 patients (15.8%) had endoscopic findings consistent with the diagnosis of CD. Eighteen of these 19 patients (95%) with positive findings on CE had previously undergone SBFT examination, and only one patient showed findings consistent with CD.

CD is characterized by the presence of chronic inflammatory infiltrates and fibrosis. Early treatment of CD may improve these conditions. Therefore, early diagnosis of CD is preferable for improving the suspected CD conditions. Small bowel endoscopy can help in the early detection of active disease, thus leading to early therapy before the onset of clinical symptoms of established CD. Longitudinal ulcers on the mesenteric side of the small bowel, a cobblestone-like mucosal appearance, stenosis, aphthous ulcers, fissures, and fistulas are typically observed in established CD; however, it has not yet been established that the diagnostic criteria of early CD mainly depend on endoscopic findings.

Mehdizadeh et al.34 reported the diagnostic yield of CE in patients with CD; 52 of 134 patients (39%) with CD had CE findings diagnostic of active CD (>3 ulceration), and 17 patients (13%) had findings suggestive of active CD (≤3 ulceration), i.e., defined small bowel ulcers that were serpiginous, deep fissuring, coalescing, linear, or nodular. It is unclear whether the number of ulcers is important to diagnose CD. It is desirable to collect early endoscopic findings of CD and to establish how definite diagnosis of CD can be made in suspected CD patients by only using the endoscopic findings. This is because tiny mucosal lesions can be observed in 13% of normal, asymptomatic individuals by using CE,6 and high sensitivities (77% to 93%) of CE for diagnosis of CD in patients have been reported;35-37 however, a low positive predictive value of CE has also been reported.36 Small bowel endoscopy can help in the analysis of the location and activity of active small bowel CD. These findings can help us to evaluate the effectiveness of current medical therapy and to determine the best therapeutic strategy.

Computed tomography enterography (CTE) and magnetic resonance enterography (MRE) are useful diagnostic tools in patients with CD, especially for detecting intramural and extraluminal pathology such as fistulas, abscesses, and thickening of the intestinal wall in patients with CD. Previous studies comparing the effectiveness of CTE and MRE have shown similar sensitivities and specificities of these techniques for detection of small intestinal CD.38,39 In recent studies, CTE and MRE showed similar accuracies in detecting active inflammation; however, MRE was significantly more sensitive than was CTE in detecting fibrosis.40 A recent meta-analysis of patient with suspected and established CD demonstrated a significantly increased diagnostic yield of CE compared with that of small bowel radiography, CTE, conventional ileocolonoscopy, and push enteroscopy.41 Jensen et al.42 reported that CE had comparable sensitivity and specificity for diagnosis of CD of the terminal ileum with CTE and MRE, and proximal CD was detected in 18 of 87 patients by using CE, compared with two and six patients by using CTE and MRE, respectively.

Although CD was originally described as regional ileitis, a chronic inflammatory disease restricted to the terminal ileum, previous reviews have estimated that 40% to 55% of the patients have ileocecal involvement, 15% to 25% have colonic involvement, and 25% to 40% have small bowel involvement.43,44 Conventional ileocolonoscopy can be used to evaluate the colon and the terminal ileum, which is the most common site of small bowel involvement in patients with CD. However, some patients with CD have mucosal inflammatory changes not in the terminal ileum but in the proximal small bowel, and conventional ileocolonoscopy cannot detect ileal involvement proximal to the terminal ileum. Recently Samuel et al.45 reported that ileocolonoscopy, compared with CTE, is not sufficient for evaluating small bowel involvement. Of 153 patients with CD who underwent both CTE and ileocolonoscopy with terminal ileum intubation, 67 patients (44%) revealed no terminal ileum involvement macroscopically, and of these 67 patients, 36 (54%) were considered to have active CD based on the referential standard. Of these 36 patients, 11 patients showed active small bowel involvements that were beyond the reach of conventional ileocolonoscopy. BAE, not conventional ileocolonoscopy, may be useful for the evaluation of small bowel involvement in CD. BAE can be used to examine the deep small bowel, and BAE revealed small bowel disease activity that was beyond the reach of conventional endoscopy in 60% to 89% of the patients.23,24 Oshitani et al.23 reported that, of 38 CD patients who underwent DBE for evaluation of small bowel involvement, seven patients had terminal ileum disease, and ileal involvement proximal to the terminal ileum was revealed in 27 CD patients. Of these 27 patients, 24 patients (89%) had no involvement of the terminal ileum.

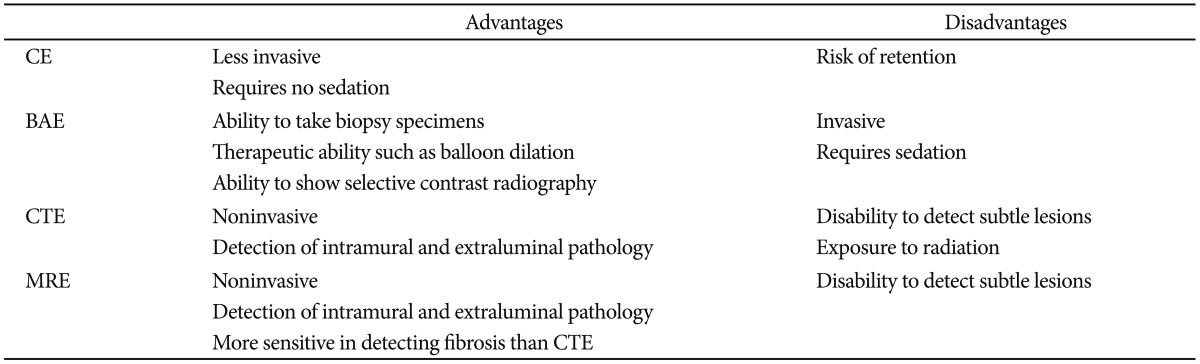

Although small bowel endoscopy is useful in the management of CD, the number of unnecessary endoscopic procedures should be reduced with regard to the cost-effectiveness and invasiveness of the procedures. CTE is a cost-effective alternative to SBFT in patients with suspected small bowel CD, and CE is not a cost-effective approach when used as the third diagnostic test after ileocolonoscopy and negative CTE or SBFT.46 The level of the acute-phase protein fecal calprotectin can be a surrogate marker for the presence of gastrointestinal inflammation. A recent meta-analysis showed that fecal calprotectin had a sensitivity of 93% for detecting inflammatory bowel diseases including both UC and CD.47 Particularly in CD, the utility of fecal calprotectin remains inconclusive. A study evaluating the utility of calprotectin in the diagnosis of CD has shown that the sensitivity of fecal calprotectin in patients with isolated small bowel CD and colonic CD is 92% and 94%, respectively, and that the negative predictive value of fecal calprotectin is 92%.48 Koulaouzidis et al.49 reported in their retrospective study that 32 patients who had fecal calprotectin <100 g/g had normal CE findings, and 15 of 35 patients who had fecal calprotectin >100 g/g had CE findings compatible with those for CD; therefore, fecal calprotectin is a useful marker to rule out CD and select patients for small bowel endoscopy. In contrast, Sipponen et al.50 reported in their prospective study that fecal calprotectin has moderate specificity (71%) but low sensitivity (59%) in predicting small bowel changes, and therefore, it cannot be used for screening or excluding small bowel CD. Further study is desirable to determine the role of fecal calprotectin as a surrogate marker for the presence of active small bowel lesions in patients with CD. Table 2 shows the relative advantages and disadvantages of the modalities used for evaluating the small bowel.

Intestinal strictures are common complications associated with CD and a major cause of hospitalization and surgery. In the long term, multiple resections may be associated with short-bowel syndrome. Strictureplasty is recognized as a surgical alternative. In a meta-analysis of strictureplasty for CD, the recurrence rate of CD after strictureplasty was increased in patients with a longer study duration after surgery.51 EBD has been used to treat CD-related strictures as an alternative to surgery. This technique can be considered in patients presenting with obstructive symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and bloating. A stricture is usually regarded as unsuitable for EBD if it is longer than 5 cm and has a fistula, deep ulcer, severe curvature, or abscess. A wire-guided through-the-scope balloon dilator is commonly used for dilating. First, a guide wire is inserted through the stenosis under radiological control; then, a balloon catheter is positioned appropriately, and the balloon is inflated while monitoring the pressure with a gauge.

Multiple stenoses can be dilated sequentially. However, a dilated segment of the small bowel is friable. Therefore, when inserting the endoscope at the distal side after dilation, attention should be paid when setting the overtube at an appropriate position to avoid inflating the balloon of the overtube at the already dilated segment. Although no differences in the number of strictures have been reported between successful and unsuccessful EBD,52 which patients with multiple strictures should undergo EBD or surgical therapy remains unknown.

Although there are several studies with a small patient size, the rate of severe complications such as intestinal perforation, bleeding, or acute pancreatitis on small bowel EBD is 8% to 9%.52,53 Both a short-term outcome and a long-term surgery-free rate after EBD are important. It was reported that the cumulative surgery-free rate after EBD is 60% to 83%;52,54,55 however, it is difficult to evaluate the long-term outcome because the surgery-free period after EBD differs in each study. Further examination regarding the long-term efficacy after EBD is desirable.

Small bowel endoscopic procedures such as CE, BAE, and spiral endoscopy have been developed. CE is a noninvasive method that requires no sedation, and BAE can be performed without worrying about capsule retention and biopsy specimen collection and can be used to dilate strictures. Both modalities have complementary roles in small bowel endoscopy.

Small bowel endoscopy helps with the differential diagnosis of CD in suspected CD patients. Early diagnosis of CD is preferable for suspected CD conditions to improve chronic inflammatory infiltrates, fibrosis. Small bowel endoscopy can help with the early detection of active disease, thus leading to early therapy before the onset of clinical symptoms of established CD. Some patients with CD have mucosal inflammatory changes not in the terminal ileum but in the proximal small bowel. Conventional ileocolonoscopy cannot detect ileal involvement proximal to the terminal ileum. Small bowel endoscopy, however, can be useful for evaluating these small bowel involvements in patients with CD. Small bowel endoscopy by EBD enables the treatment of small bowel strictures in patients with CD. However, many practical issues still need to be addressed, such as endoscopic findings for early detection of CD, application compared with other imaging modalities such as CTE, MRE or fecal biomarkers, determination of the appropriate interval for endoscopic surveillance of small bowel lesions in patients with CD, and long-term prognosis after EBD.

Small bowel endoscopy has been developed in diagnosing and treating CD, the ways of management for CD also have been developed in connection with development of small bowel endoscopy.

References

1. Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000; 405:417. PMID: 10839527.

2. Kim HM, Yang S, Kim J, et al. Active locomotion of a paddling-based capsule endoscope in an in vitro and in vivo experiment (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 72:381–387. PMID: 20497903.

3. Karagiannis S, Faiss S, Mavrogiannis C. Capsule retention: a feared complication of wireless capsule endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2009; 44:1158–1165. PMID: 19606392.

4. Purdy M, Heikkinen M, Juvonen P, Voutilainen M, Eskelinen M. Characteristics of patients with a retained wireless capsule endoscope (WCE) necessitating laparotomy for removal of the capsule. In Vivo. 2011; 25:707–710. PMID: 21709019.

5. Höög CM, Bark LÅ, Arkani J, Gorsetman J, Broström O, Sjöqvist U. Capsule retentions and incomplete capsule endoscopy examinations: an analysis of 2300 examinations. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012; 2012:518718. PMID: 21969823.

6. Goldstein JL, Eisen GM, Lewis B, et al. Video capsule endoscopy to prospectively assess small bowel injury with celecoxib, naproxen plus omeprazole, and placebo. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005; 3:133–141. PMID: 15704047.

7. Li F, Gurudu SR, De Petris G, et al. Retention of the capsule endoscope: a single-center experience of 1000 capsule endoscopy procedures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 68:174–180. PMID: 18513723.

8. Cheon JH, Kim YS, Lee IS, et al. Can we predict spontaneous capsule passage after retention? A nationwide study to evaluate the incidence and clinical outcomes of capsule retention. Endoscopy. 2007; 39:1046–1052. PMID: 18072054.

9. Van Weyenberg SJ, Van Turenhout ST, Bouma G, et al. Double-balloon endoscopy as the primary method for small-bowel video capsule endoscope retrieval. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 71:535–541. PMID: 20189512.

10. Kim KO, Jang BI. Lessons from Korean capsule endoscopy multicenter studies. Clin Endosc. 2012; 45:290–294. PMID: 22977821.

11. Long MD, Barnes E, Isaacs K, Morgan D, Herfarth HH. Impact of capsule endoscopy on management of inflammatory bowel disease: a single tertiary care center experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011; 17:1855–1862. PMID: 21830264.

12. Cheifetz AS, Kornbluth AA, Legnani P, et al. The risk of retention of the capsule endoscope in patients with known or suspected Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006; 101:2218–2222. PMID: 16848804.

13. Lin OS, Brandabur JJ, Schembre DB, Soon MS, Kozarek RA. Acute symptomatic small bowel obstruction due to capsule impaction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 65:725–728. PMID: 17383473.

14. Parikh DA, Parikh JA, Albers GC, Chandler CF. Acute small bowel perforation after wireless capsule endoscopy in a patient with Crohn's disease: a case report. Cases J. 2009; 2:7607. PMID: 19830002.

15. Gonzalez Carro P, Picazo Yuste J, Fernández Díez S, Pérez Roldán F, Roncero García-Escribano O. Intestinal perforation due to retained wireless capsule endoscope. Endoscopy. 2005; 37:684. PMID: 16010621.

16. Um S, Poblete H, Zavotsky J. Small bowel perforation caused by an impacted endocapsule. Endoscopy. 2008; 40(Suppl 2):E122–E123. PMID: 18633864.

17. Repici A, Barbon V, De Angelis C, et al. Acute small-bowel perforation secondary to capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:180–183. PMID: 17981271.

18. Tanaka S, Mitsui K, Shirakawa K, et al. Successful retrieval of video capsule endoscopy retained at ileal stenosis of Crohn's disease using double-balloon endoscopy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006; 21:922–923. PMID: 16704551.

19. Al-toma A, Hadithi M, Heine D, Jacobs M, Mulder C. Retrieval of a video capsule endoscope by using a double-balloon endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 62:613. PMID: 16185982.

20. May A, Nachbar L, Ell C. Extraction of entrapped capsules from the small bowel by means of push-and-pull enteroscopy with the double-balloon technique. Endoscopy. 2005; 37:591–593. PMID: 15933937.

21. Lee BI, Choi H, Choi KY, et al. Retrieval of a retained capsule endoscope by double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005; 62:463–465. PMID: 16111977.

22. Sunada K, Yamamoto H. Double-balloon endoscopy: past, present, and future. J Gastroenterol. 2009; 44:1–12. PMID: 19159069.

23. Oshitani N, Yukawa T, Yamagami H, et al. Evaluation of deep small bowel involvement by double-balloon enteroscopy in Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006; 101:1484–1489. PMID: 16863550.

24. de Ridder L, Mensink PB, Lequin MH, et al. Single-balloon enteroscopy, magnetic resonance enterography, and abdominal US useful for evaluation of small-bowel disease in children with (suspected) Crohn's disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012; 75:87–94. PMID: 21963066.

25. Mensink PB, Haringsma J, Kucharzik T, et al. Complications of double balloon enteroscopy: a multicenter survey. Endoscopy. 2007; 39:613–615. PMID: 17516287.

26. Akerman PA, Agrawal D, Cantero D, Pangtay J. Spiral enteroscopy with the new DSB overtube: a novel technique for deep peroral small-bowel intubation. Endoscopy. 2008; 40:974–978. PMID: 19065477.

27. Williamson JB, Judah JR, Gaidos JK, et al. Prospective evaluation of the long-term outcomes after deep small-bowel spiral enteroscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012; 76:771–778. PMID: 22771101.

28. Buscaglia JM, Richards R, Wilkinson MN, et al. Diagnostic yield of spiral enteroscopy when performed for the evaluation of abnormal capsule endoscopy findings. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011; 45:342–346. PMID: 20861800.

29. Frieling T, Heise J, Sassenrath W, Hülsdonk A, Kreysel C. Prospective comparison between double-balloon enteroscopy and spiral enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2010; 42:885–888. PMID: 20803420.

30. May A, Manner H, Aschmoneit I, Ell C. Prospective, cross-over, single-center trial comparing oral double-balloon enteroscopy and oral spiral enteroscopy in patients with suspected small-bowel vascular malformations. Endoscopy. 2011; 43:477–483. PMID: 21437852.

31. Morgan D, Upchurch B, Draganov P, et al. Spiral enteroscopy: prospective U.S. multicenter study in patients with small-bowel disorders. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 72:992–998. PMID: 20870226.

32. Ramchandani M, Reddy DN, Gupta R, et al. Spiral enteroscopy: a preliminary experience in Asian population. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 25:1754–1757. PMID: 21039837.

33. Mehdizadeh S, Chen G, Enayati PJ, et al. Diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy in ulcerative colitis and inflammatory bowel disease of unclassified type (IBDU). Endoscopy. 2008; 40:30–35. PMID: 18058654.

34. Mehdizadeh S, Chen GC, Barkodar L, et al. Capsule endoscopy in patients with Crohn's disease: diagnostic yield and safety. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 71:121–127. PMID: 19863957.

35. Girelli CM, Porta P, Malacrida V, Barzaghi F, Rocca F. Clinical outcome of patients examined by capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2007; 39:148–154. PMID: 17196893.

36. Tukey M, Pleskow D, Legnani P, Cheifetz AS, Moss AC. The utility of capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104:2734–2739. PMID: 19584828.

37. Figueiredo P, Almeida N, Lopes S, et al. Small-bowel capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected Crohn's disease-diagnostic value and complications. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2010; 2010:pii: 101284.

38. Siddiki HA, Fidler JL, Fletcher JG, et al. Prospective comparison of state-of-the-art MR enterography and CT enterography in small-bowel Crohn's disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009; 193:113–121. PMID: 19542402.

39. Fiorino G, Bonifacio C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Prospective comparison of computed tomography enterography and magnetic resonance enterography for assessment of disease activity and complications in ileocolonic Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011; 17:1073–1080. PMID: 21484958.

40. Quencer KB, Nimkin K, Mino-Kenudson M, Gee MS. Detecting active inflammation and fibrosis in pediatric Crohn's disease: prospective evaluation of MR-E and CT-E. Abdom Imaging. Epub 2013 Jan 30. DOI: 0.1007/s00261-013-9981-z.

41. Dionisio PM, Gurudu SR, Leighton JA, et al. Capsule endoscopy has a significantly higher diagnostic yield in patients with suspected and established small-bowel Crohn's disease: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:1240–1248. PMID: 20029412.

42. Jensen MD, Nathan T, Rafaelsen SR, Kjeldsen J. Diagnostic accuracy of capsule endoscopy for small bowel Crohn's disease is superior to that of MR enterography or CT enterography. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011; 9:124–129. PMID: 21056692.

43. Nikolaus S, Schreiber S. Diagnostics of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2007; 133:1670–1689. PMID: 17983810.

44. Ng SC, Tang W, Ching J, et al. Incidence and phenotype of inflammatory bowel disease based on results from the Asia-pacific Crohn's and colitis epidemiology study. Gastroenterology. 2013; 145:158–165. PMID: 23583432.

45. Samuel S, Bruining DH, Loftus EV Jr, et al. Endoscopic skipping of the distal terminal ileum in Crohn's disease can lead to negative results from ileocolonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012; 10:1253–1259. PMID: 22503995.

46. Levesque BG, Cipriano LE, Chang SL, Lee KK, Owens DK, Garber AM. Cost effectiveness of alternative imaging strategies for the diagnosis of small-bowel Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010; 8:261–267. PMID: 19896559.

47. van Rheenen PF, Van de Vijver E, Fidler V. Faecal calprotectin for screening of patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease: diagnostic meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010; 341:c3369. PMID: 20634346.

48. Jensen MD, Kjeldsen J, Nathan T. Fecal calprotectin is equally sensitive in Crohn's disease affecting the small bowel and colon. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011; 46:694–700. PMID: 21456899.

49. Koulaouzidis A, Douglas S, Rogers MA, Arnott ID, Plevris JN. Fecal calprotectin: a selection tool for small bowel capsule endoscopy in suspected IBD with prior negative bi-directional endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2011; 46:561–566. PMID: 21269246.

50. Sipponen T, Haapamäki J, Savilahti E, et al. Fecal calprotectin and S100A12 have low utility in prediction of small bowel Crohn's disease detected by wireless capsule endoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012; 47:778–784. PMID: 22519419.

51. Tichansky D, Cagir B, Yoo E, Marcus SM, Fry RD. Strictureplasty for Crohn's disease: meta-analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000; 43:911–919. PMID: 10910235.

52. Hirai F, Beppu T, Sou S, Seki T, Yao K, Matsui T. Endoscopic balloon dilatation using double-balloon endoscopy is a useful and safe treatment for small intestinal strictures in Crohn's disease. Dig Endosc. 2010; 22:200–204. PMID: 20642609.

53. Despott EJ, Gupta A, Burling D, et al. Effective dilation of small-bowel strictures by double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with symptomatic Crohn's disease (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 70:1030–1036. PMID: 19640518.

54. Pohl J, May A, Nachbar L, Ell C. Diagnostic and therapeutic yield of push-and-pull enteroscopy for symptomatic small bowel Crohn's disease strictures. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; 19:529–534. PMID: 17556897.

55. Fukumoto A, Tanaka S, Yamamoto H, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of small-bowel stricture by double balloon endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 66(3 Suppl):S108–S112. PMID: 17709019.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download