One of the most feared complications might be perforation. Though ERCP-related perforation has been reported in less than 1%, mostly in association with sphincterotomy,

2,

4 perforation needs to be diagnosed immediately and should be treated promptly, since delayed diagnosis and intervention of perforation may lead to the development of sepsis and multiorgan failure, which are the causes of higher mortality (8% to 23%).

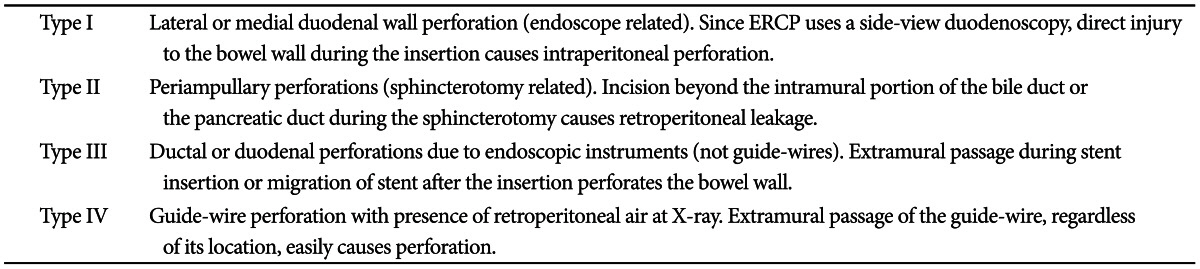

5 The most commonly used classification of ERCP-induced perforation is the one suggested by Stapfer et al.,

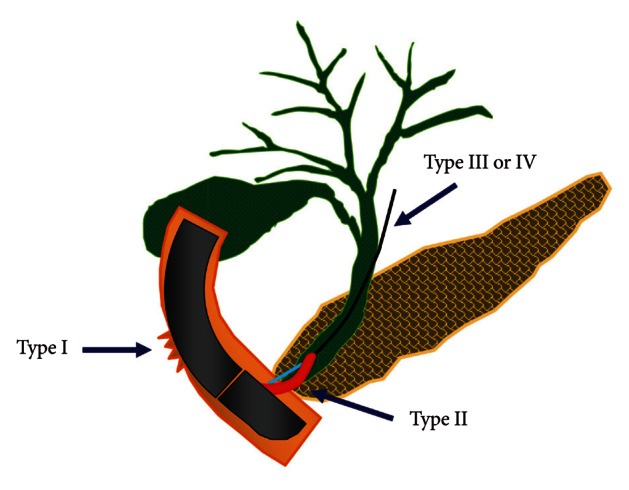

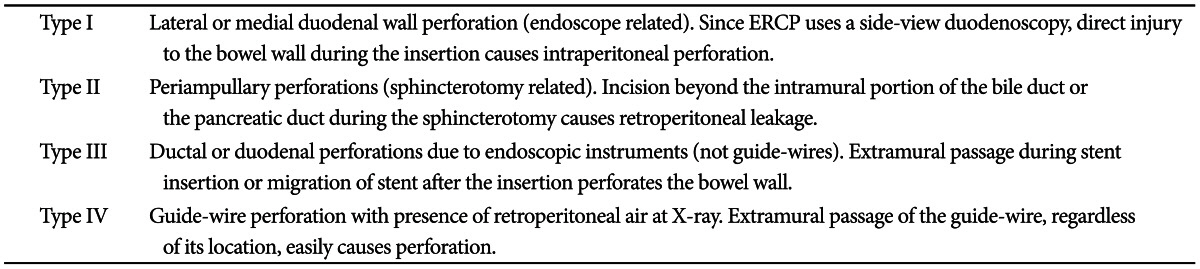

6 which is set up based on its mechanism and can predict the need for surgery depending on the anatomic location and severity of injury. According to this classification, ERCP-induced perforation can be categorized into four types (

Table 1,

Fig. 1). Risk factors associated with perforation are not clearly identified due to the low incidence. However, the incidence of bowel perforation is more frequent in patients who received Billoth II gastrectomy or roux-en-Y operation, while sphincterotomy perforation is more common during precut method with a needle knife or in patients suspected of SOD dysfunction.

1 Usual conservative medical managment requires nasobiliary drain to avoid bile spillage, with nasogastric tube draining to prevent infiltration of intestinal contents into the retroduodenal space. These treatments should be accompanied by intravenous antibiotics, strict fasting, and surgical consultation as well.

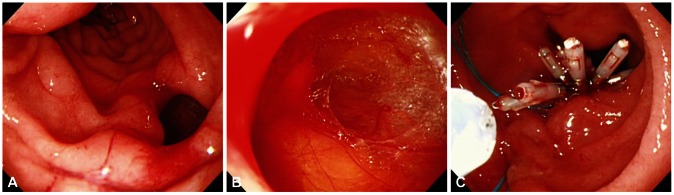

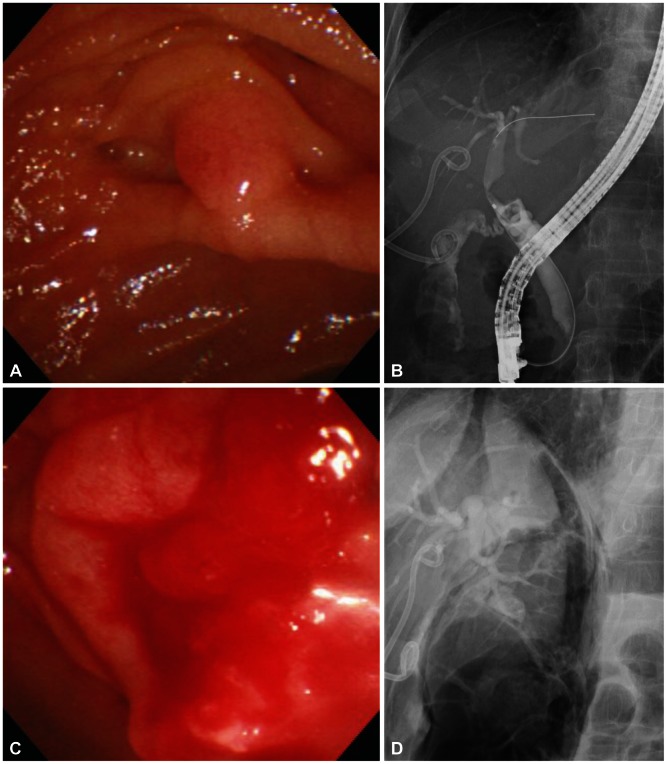

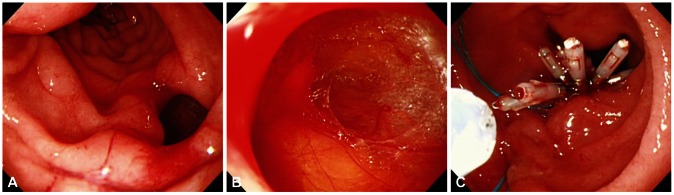

2 The treatment of post-ERCP perforation should be determined based on the type and severity of the leak and clinical manifestations. For type I and type II perforations, surgical treatment is generally recommended, although recent development of endoscopic treatments enabled successful treatment with endoscopic clippings, endoloop applications, and endoscopic closure devices (

Figs. 2-

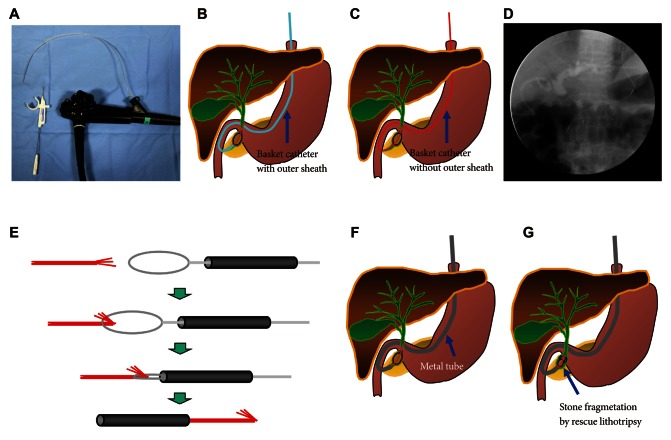

4). Guide-wire or stent-related extramural perforations can be treated easily with endoscopic treatment using adequate ductal drainage above the leak site.

7-

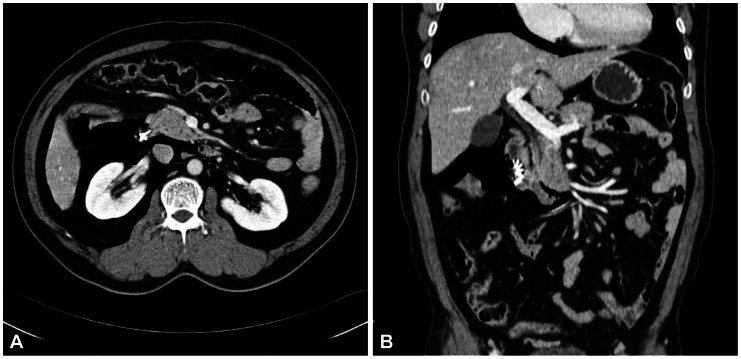

9 Sphincterotomy-related perforation, unlike other types of perforations, can be fully prevented. Limiting the length of cutting wire for sphincterotome that touches the tissues or using stepwise incisions is a safer way of preventing perforations. If perforation is suspected during sphincterotomy, extraluminal leakage can be identified by injecting a small amount contrast while passing the inserted catheter or papillotome by the suspected site of perforation following the guide-wire under the fluoroscopic guidance. Identified perforation, regardless of its type, should be confirmed for any presence of contrast leakage and retroperitoneal or intraperitoneal air with abdominal computed tomography (CT). Care should be taken, however, to make a decision based on the patient's clinical condition, since 29% of asymptomatic patients have free retroperitoneal air observed at the CT images taken within 24 hours after ERCP, which is not associated with the severity of the complication or the need for sugery.

10 Immediate closing with endoscopic clipping may be attempted for perforation sites with confirmed leakage.

9,

11 However, since clipping with a side-view duodenoscopy can be technically difficult, a cap-assisted, forward-view endoscopy may be applied. Other treatments of perforation after biliary sphincterotomy include the insertion of a fully covered self-expandable metal stent.

12-

14 Asymptomatic patients with only the evidence of free air can normally be improved with a conservative management consisting of bowel rest and antibiotics. Inappropriate biliary drainage may cause the infiltration of bile or fluid leakage into the perforated site, increasing the morbidity.

6,

8 Patients whose leakage volume is enough to be observed on CT, those with confirmed continous leakage, or whose clinical condition is deteriorating should be considered for immediate surgical approach. Since mortality due to sepsis is as high as 50% among patients with failure of conservative medical managment, surgical managmenet should not be hesitated in such patients.

2,

6 Type I and type III duodenal perforations due to endoscope tip or stent migration might be treated with endoscopic clipping.

15-

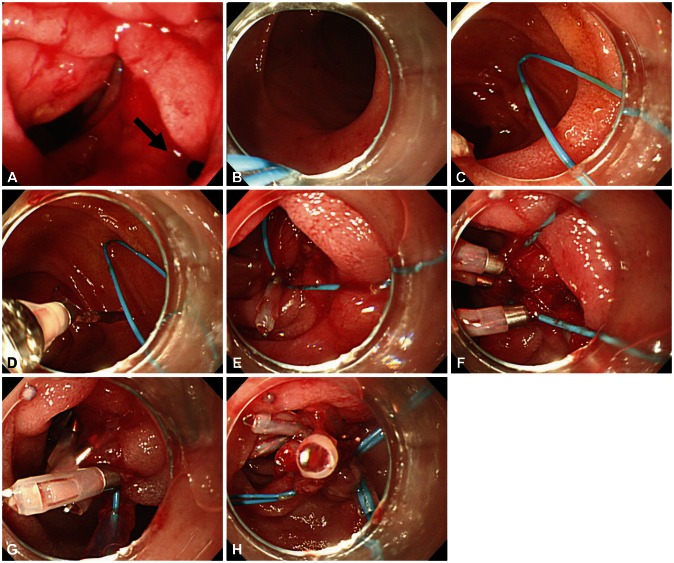

17 However, most cases of duodenoscopy-induced duodenal perforation cannot be closed with clipping only, due to the wide range of perforation. Combination of endoscopic clipping and endoloop application has been introduced to avoid operation. Since the initial report by Endo et al.,

18 there have been various clinical trials concerning the usage of an endoloop and multiple hemoclips to cover large mucosal defects following endoscopic submucosal dissection and endoscopic mucosal resection.

19,

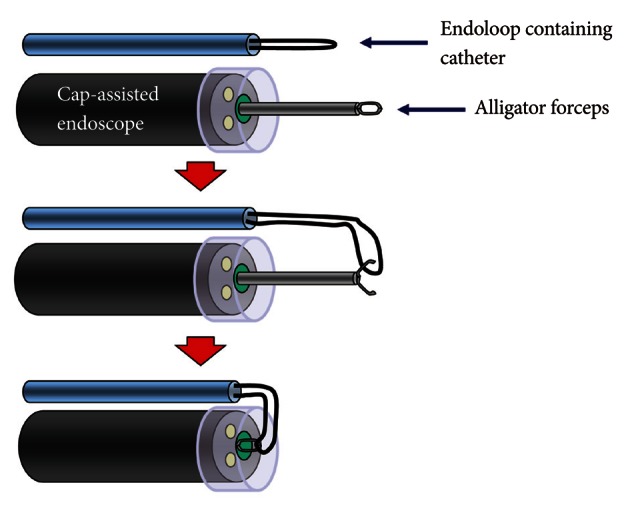

20 When perforation is suspected, relatively thin forward viewing one-channel endoscope with a cap on the tip of the endoscope (transparent cap-assisted) may as well be used for observation, while minimizing air insufflation or using CO

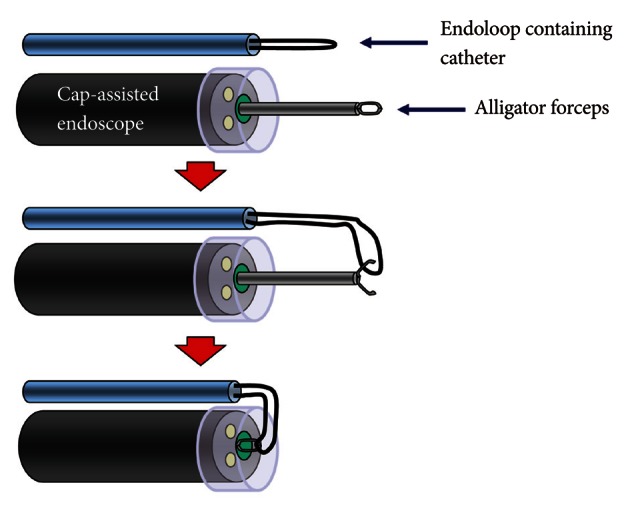

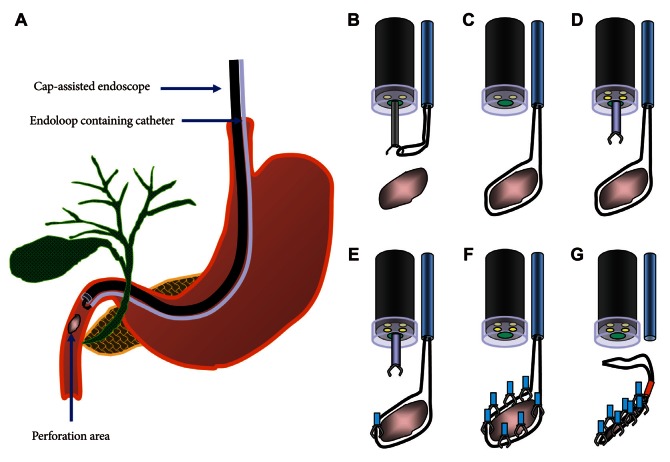

2 generator. The reason for choosing a one-channel endoscope, instead of a two-channel endoscope, is that a one-channel endoscope allows separating two catheters and it can provide a wide range of therapeutic activities during therapy. When using a two-channel endoscope, although simultaneous insertion of one catheter with an endoloop and the other catheter with a clip into each channel can fix the clips together with the endoloop, technical problems can occur in cases with a lesion difficult to access or with a narrow lumen, due to the wider diameter of the two-channel endoscope and the parallel existence of two-working channels. The combination therapy is conducted as follows (

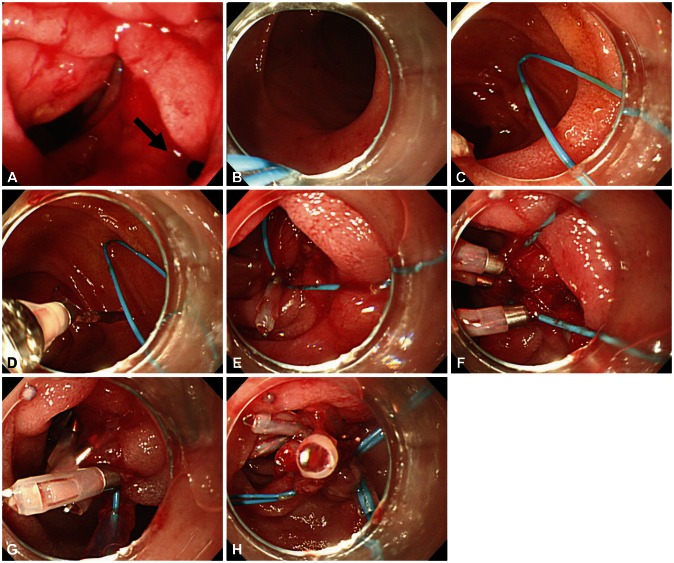

Figs. 5-

7). Before insertion of cap-assisted endoscope, an alligator forceps are inserted into the working channel of the endoscope and the alligator forceps caught the tip of an endoloop. Then, the endoloop containing the catheter and endoscope are inserted into the patient. At placement of them around the perforated area, the alligator forceps are opened for detaching the endoloop containing the catheter. Then, the endoloop containing the catheter is properly released. After insertion of the clipping catheter, the tip of the endoloop is caught with the clip and clipping is started from the distal margin. Thereafter, multiple clips are attached with the endoloop to the perforated area and vice versa (a bunch-like clip formation is caught and fixed with the endoloop). Finally, the endoloop is tightened and this closes the perforated area.

21 Change of the patient's condition should be monitored while performing conservative managements such as antibiotics, total parenteral nutrition and nasogastric tube drainage. If the clinical symptoms have not been deteriorated, upper gastrointestinal investigations using gastrograffin should be performed, following approximately 1-week period of conservative management, to ascertain whether extra-duodenal spillage is present.

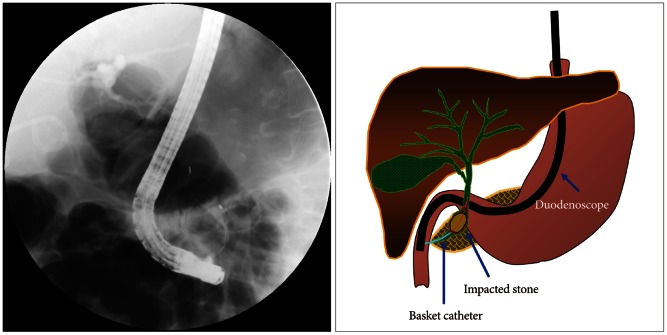

| Fig. 1The illustration of the classification of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related perforations.

|

| Fig. 2Endoscopic images of a case with type I perforation. (A) A large perforation on lateral duodenal wall. (B) Duodenal serosa and omentum is revealed. (C) Successful primary endoscopic closure using multiple clips and endoloop.

|

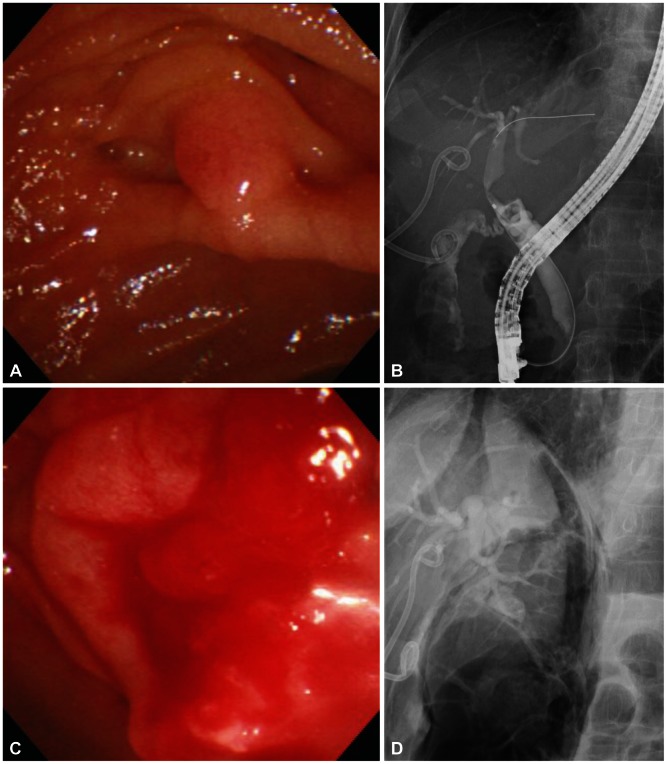

| Fig. 4Endoscopic images and cholangiograms of a case with type II perforation. (A) Endoscopic view of ampulla. (B) Cholangiogram shows mild biliary dilatation with several round filling defecs in the common bile duct. (C) Endoscopic view shows active bleeding and edematous change at the postsphincterotomy's area. (D) Cholangiogram shows unsuspected large amount of air in the retroperitoneal area.

|

| Fig. 5Illustration of cap-assisted endoscope and instruments before endoscopic combination therapy. An alligator forceps are inserted into the working channel of the endoscope and the alligator forceps caught the tip of an endoloop.

|

| Fig. 7Endoscopic images of a case with type I perforation (arrow) and successful endoscopic management. (A) A perforation is noted on lateral duodenal wall. (B) Placement of endoscope and endoloop containing catheter around the perforated area. (C) The alligator forceps are opened for detaching the endoloop containing the catheter and the endoloop containing the catheter is properly released around the perforated area. (D, E) The tip of the endoloop is caught with the clip and clipping is started from the distal margin. (F, G) Multiple clips are attached with the endoloop to the perforated area and vice versa (a bunch-like clip formation is caught and fixed with the endoloop). (H) The endoloop is tightened and this closes the perforated area, successfully.

|

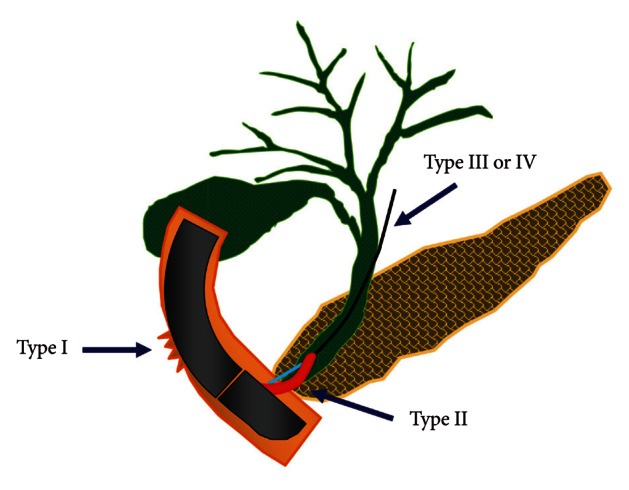

Table 1

Classification of Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiography-Related Perforations

6

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download