Abstract

Gastric protruding lesions are frequently encountered by health screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy. They can be classified into epithelial lesion and subepithelial lesion. Epithelial gastric lesions are generally divided into benign and malignant. Benign lesions include some types of polyps, i.e., hyperplastic polyp, fundic gland polyp, and gastric adenoma. Malignant lesions include carcinoid, early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer. They can be accurately diagnosed by magnifying endoscopy or narrow band imaging. Here, I will discuss benign and malignant epithelial lesions of the stomach.

Go to :

National cancer screening program discovered many asymptomatic gastric diseases including gastric polyps and early gastric cancer (EGC). Gastric polyps found by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) are divided into elevated, flat, and depressed lesion by gross morphology. Gastric elevated lesions are originated from gastric epithelial cells and nonepithelial cells. Gastric elevated lesion originated from surface epithelium can be diagnosed by magnifying endoscopy or narrow band imaging, and gastric lesion originated from subepithelial tissue can be diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasonography. Polypoid gastric cancer and the other gastric polyps including benign disease entity will be discussed herein.

Go to :

Gastric polyps are locally elevated lesion protruding into gastric lumen and incidentally discovered in about 2% of EGD.1 Most patients are asymptomatic, but infrequently, complications such as bleeding or gastric obstruction can be accompanied. Endoscopic appearance is usually salmon pink or red colored and they are sessile, semipedunculated, or pedunculated in shape. Topographically, fundic gland polyp (FGP) usually occurs in the body or fundus and adenoma usually occurs in the antrum. Some polyps such as hyperplastic polyps, FGP, carcinoids, and metastases tend to be multiple lesions. Some polyps tend to have malignant transformation (FGP, adenoma, and carcinoid), while hyperplastic polyps, inflammatory fibrinoid polyps, and hamartomatous polyps are seldom known to have malignant transformation.

These polyps are the second common gastric polyp after FGP.2 They are sessile or pedunculated shape grossly. They have wide age range distribution but are more common with increasing age (mean, 65.5 to 75 years). The 58% to 70.5% of the patients are women and a slightly lower incidence in men.3 Geographically, 24% to 60% of hyperplastic polyps are located in the antrum, 29% to 56.3% in the body and fundus, and 2.5% in the cardia.4 About two thirds of hyperplastic polyps are single, and the size of hyperplastic polyps is usually less than 1 cm. However, 10% of hyperplastic polyps are more than 2 cm in size according to one series.4

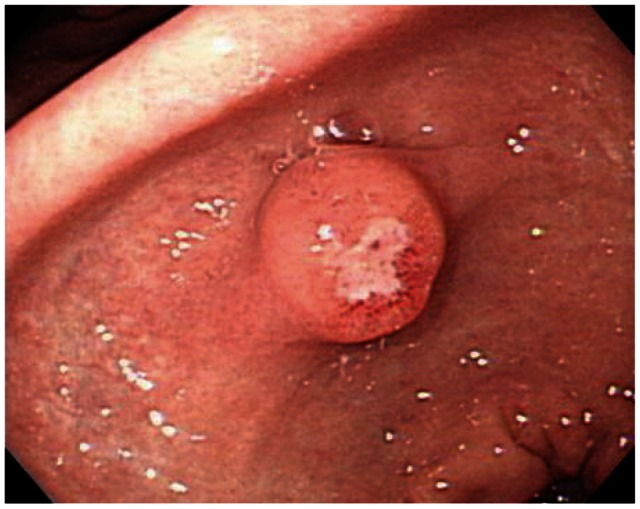

The etiology of hyperplastic polyp is idiopathic. They are thought to result from excessive regeneration of foveolar epithelium after mucosal damage. The 25% of hyperplastic polyps are accompanied by Helicobacter pylori related gastritis, and they commonly occur in pernicious anemia, adjacent to ulcers, erosions, or at anastomotic site after gastroenterostomy (Fig. 1). Histologic findings are elongated and distorted gastric pits lined by foveolar epithelium with branching, resulting in corkscrew appearance or in cystic dilatation. Another feature is the excess of edematous lamina propria inflamed by plasma cells, lymphocytes, eosinophils, mast cells, macrophages, and neutrophils.

Endoscopic findings are elevated mucosa or red colored lesion compared with adjacent mucosa. Easy contact bleeding, and small erosion or ulceration or plaque are commonly seen on the surface of polyps. Most cases are asymptomatic but bleeding may result in anemia especially in cases of large in size or multiple in number. Hyperplastic polyps tend to regress after H. pylori eradication or may be increased in number without any treatment. In Korea, according to one series, 90% of hyperplastic polyps, especially those of less than 10 mm in diameter or in sessile type, regressed after H. pylori eradication.5

H. pylori eradication can replace endoscopic removal of polyps in sessile lesion if accompanied by H. pylori gastritis.

For hyperplastic polyps, especially of more than 1 to 2 cm in diameter, polypectomy is recommended because of the increased possibility of bleeding and malignant transformation; however, regular follow-up endoscopy is recommended for smaller lesions of less than 1 cm in diameter.6 The incidence of malignant transformation in hyperplastic polyp is reported between 1.5% to 3%.7 Malignant transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps had significant relationships with >1 cm in size, pedunculated shape, postgastectomy state, and synchronous neoplastic lesion. Therefore, endoscopic polypectomy should be considered in these hyperplastic polyps to avoid the risk of missing neoplastic potential.8

Vanek9 first described this lesion as gastric submucosal granuloma with eosinophilic infiltration in 1949. Histologically, this lesion shows proliferated spindle cells, abundant small blood vessels, and infiltration of inflammatory cells, especially dominated by eosinophils. Inflammatory fibroid polyp can be seen throughout the gastrointestinal tract, but usually occurs in antropyloric region (about 80%). This lesion is associated in some cases with hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria, although accurate etiology is unknown. Allergic cause has been suggested to play a role but no specific cause has been identified until now.

Inflammatory fibroid polyp is well-circumscribed, solitary, small sessile, or pedunculated mass and can be ulcerated (Fig. 2). Clinically, most polyps are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally. Polypectomy is an effective diagnostic procedure and treatment without recurrence.

Go to :

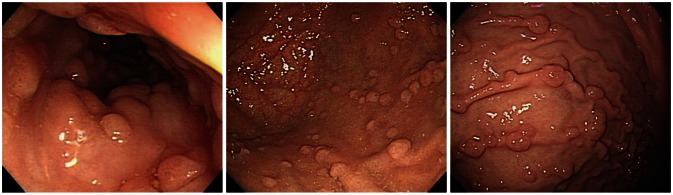

Elster10 first described FGP in 1976. Histologically, FGP is composed of cystically dilated glands lined by fundic epithelium (parietal cell, chief cell, admixed with normal glands) and most common gastric polyp. Endoscopically, this polyp is sessile and less than 0.5 cm in mean diameter. FGP appears as glassy, transparent, and of the same color as adjacent normal mucosa. FGP is multiple or single mass and occurs in the fundus or body mucosa which secrete gastric acid. Adjacent mucosa is usually clear without inflammation or H. pylori infection.

FGPs are usually multiple especially associated with familial adenomatous polyposis or Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and may be found in men and women of relatively young age (Fig. 3). The frequent finding of genetic alteration in familial adenomatous polyposis suggests that this polyp is neoplastic rather than hamartomatous origin.11 Recently, one series reported adenocarcinoma arising from FGPs in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis or attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis.12,13 FGPs especially in young age and multiple in number might be associated with familial adenomatous polyposis, and these cases were accompanied by dysplasia in up to 40%.14

Sporadic FGP is usually found in middle aged women with accompanying dysplasia at the incidence of 0% to 5%, but it is not related to malignant transformation. Alteration of the β-catenin gene is found in 91% of patients and these patients have higher risk for colonic polyp, adenoma, and adenocarcinoma compared with control group which has no FGP.15

Recently, FGP is known to be one of the side effects related to proton pump inhibitor. In patients using proton pump inhibitors, there is associated hypertrophy and hyperplasia of parietal cells, and long standing exposure to this drug may increase FGPs by 4-folds compared with control group.16 However, dysplasia related to proton pump inhibitor is still rare and further study will be necessary in the future.

Go to :

Gastric adenoma is circumscribed, polypoid lesions composed of either tubular and/or villous structures lined by dysplastic epithelium. Adenoma is a precursor lesion of adenocarcinoma. Gastric adenoma is subdivided into low grade dysplasia and high grade dysplasia according to the degree of dysplasia (based on the degree of nuclear crowding, hyperchromasia, stratification, mitotic activity, cytoplasmic differentiation, and architectural distortion). Most gastric adenomas arise in the background of atrophic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia. The incidence of adenoma increases with age and adenocarcinoma arising from adenoma is reported up to 9% to 20%.17 The majority of gastric adenomas are found in the antrum and angle and secondly in the fundus. Endoscopic finding is solitary, exophytic sessile, or pedunculated mass and rarely flattened or slightly depressed lesion. Adenomas have light red color and show papillary configuration. Easy contact bleeding is not a typical finding of gastric adenoma usually measuring up to 3 to 4 cm in diameter. Adenomas of larger size, especially of more than 2 cm in diameter, with red color, central depression, ulcer, and villous configuration are known to have increased risk of carcinomatous transformation. According to one series, 9% of low grade adenomas and 25% of high grade adenomas showed the evidence of malignant transformation.18 Even when endoscopic biopsy reveals adenoma, there might be carcinomatous change in excised specimen, so gastric adenoma should be treated by local excision, usually by endoscopic mucosal resection, and needs to be followed up. In addition, since they may be accompanied by coexistent carcinoma elsewhere in the stomach, thorough endoscopic examination of the whole stomach is warranted.

Go to :

Gastric carcinoids are well-differentiated endocrine tumors composed of nonfunctioning enterochromaffin-like cells arising in the oxyntic mucosa of the body or fundus.19 Gastric carcinoids account for less than 2% of gastric neoplasm, and represents less than 1% of carcinoids.20 There are three distinct clinical settings: autoimmune atrophic gastritis, patients with concomitant Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and MEN-1 syndrome, and sporadic case.21 In the first two cases, they are usually multiple, broad-based, yellowish, polypoid masses of less than 2 cm in diameter. In the sporadic cases, the tumors are larger and single and similar to carcinoma (bleeding, obstruction, or metastases). Endoscopic ultrasonographic finding is well demarcated, homogenous and hypoechoic submucosal mass. They grow slowly but can metastasize to lymph node or the liver. The size, invasiveness and histologic subtype of mass correlates with the probability of metastasis. Treatment is dependent on the size and histologic subtype. Carcinoids less than 1 to 2 cm in size, less than five in number and confined within the submucosal layer can be treated by endoscopic mucosal resection. Surgical local excision is recommended for carconoids larger than 2 cm in size.

Go to :

EGC is defined as invasive gastric cancer which invades no more deeply than the submucosa, irrespective of lymph node metastasis. Endoscopically, there are three subtypes of polypoid EGC: elevated (type I), superficial elevated (type IIa), and mixed type (IIa+IIc, etc). Also among advanced gastric cancer (AGC), Bormann type I and II are polypoid gastric cancer.

This type shows sessile or semipedunculated hemisphere-shaped mucosal mass. They are more than 5 mm in height or 2- to 3-folds higher than the adjacent mucosa. They are occasionally accompanied by bleeding and show granular or erosive appearance on endoscopic examination. They are usually more than 2 cm in size, but smaller lesions of less than 2 cm are usually confined within the mucosa, sessile, smooth surfaced, with rare bleeding and no exudate. Differential diagnoses include adenomatous polyp, submucosal tumor (SMT), and advanced Bormann type I cancer.22

This type is not 2- to 3-folds higher than the adjacent mucosa. They are relatively well demarcated, larger in size (usually more than 2 cm), and show irregular surface, redness, erosion, ulceration, bleeding, mucosal depression, and loss of glistening. Dysplasia and atrophic hyperplastic gastritis are the main differential diagnoses. Atrophic hyperplastic gastritis is ill defined lesion and might be disappeared after changing the position of endoscopic probe or movement of peristalsis.23

This type has two or more lesions mixed, with several subtypes, such as IIa+IIc type and IIc+IIa type. EGC IIa+IIc type has shallow depressed lesion (IIc) in the center of slightly elevated lesion (IIa). If IIa lesion is the main lesion, it is classified as IIa+IIc, although IIc might be deep. Histologically, this subtype is usually a well differentiated tumor, and erosive type and advanced tumor like lesion have a tendency to have deep invasion. Verrucous erosion, EGC IIa, EGC IIc, and Bormann type 2 AGC are the main differential diagnoses.

AGC is classified as the Borrmann types based on the characteristic macroscopic morphology. Borrmann type I AGC represents polypoid fungating mass protruding into the gastric lumen. This type is well defined and shows small erosion, or shallow ulcer with exudates, rarely with deep depressive. The size of the tumor is large, usually more than 2 cm, and the surface mucosa shows coarse, irregular pit pattern with easy contact bleeding. Bormann type IV AGC (linitis plastica) also shows elevated lesion with mucosal hypertrophy.

In Japan, SMT-like gastric cancer is defined as radiologic and endoscopic finding that shows SMT-like mass. Grossly or histologically, the longest diameter of the mucosal exposed mass is less than 1/3 of the longest diameter of hidden tumor mass.24 This type has following three these characteristics: 1) slightly elevated and irregular surface; 2) larger size in unexposed portion; and 3) more frequent redness and erosion on the surface similar with SMT, in endoscopic finding.25 In Korea, SMT-like gastric cancer with mucinous adenocarcinoma was reported in one series.26,27

Go to :

Various subtypes of gastric polyps with different risks of malignant transformation which are similar with polypoid gastric cancer were revealed in endoscopic procedure. Although benign and malignant gastric polypoid tumor can be revealed in endoscopic procedure, magnifying endoscopy or narrow band imaging, and endoscopic ultrasonography could help their differential diagnosis and therapeutic strategies more easily. Most of all, meticulous endoscopic examination, accurate biopsy for indefinite lesion, reconsidering result with pathologic reports, and periodic follow-up examination are critical.

Go to :

References

1. Dekker W. Clinical relevance of gastric and duodenal polyps. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1990; 178:7–12. PMID: 2277971.

2. Stolte M, Sticht T, Eidt S, Ebert D, Finkenzeller G. Frequency, location, and age and sex distribution of various types of gastric polyp. Endoscopy. 1994; 26:659–665. PMID: 7859674.

3. Park do Y, Lauwers GY. Gastric polyps: classification and management. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008; 132:633–640. PMID: 18384215.

4. Abraham SC, Singh VK, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Hyperplastic polyps of the stomach: associations with histologic patterns of gastritis and gastric atrophy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001; 25:500–507. PMID: 11257625.

5. Lim SA, Yun JW, Yoon D, et al. Regression of hyperplastic gastric polyp after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 42:74–82.

6. Ji F, Wang ZW, Ning JW, Wang QY, Chen JY, Li YM. Effect of drug treatment on hyperplastic gastric polyps infected with Helicobacter pylori: a randomized, controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006; 12:1770–1773. PMID: 16586550.

7. Hattori T. Morphological range of hyperplastic polyps and carcinomas arising in hyperplastic polyps of the stomach. J Clin Pathol. 1985; 38:622–630. PMID: 4008664.

8. Kang HM, Oh TH, Seo JY, et al. Clinical factors predicting for neoplastic transformation of gastric hyperplastic polyps. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011; 58:184–189. PMID: 22042418.

9. Vanek J. Gastric submucosal granuloma with eosinophilic infiltration. Am J Pathol. 1949; 25:397–411. PMID: 18127133.

10. Elster K. Histologic classification of gastric polyps. Curr Top Pathol. 1976; 63:77–93. PMID: 795617.

11. Torbenson M, Lee JH, Cruz-Correa M, et al. Sporadic fundic gland polyposis: a clinical, histological, and molecular analysis. Mod Pathol. 2002; 15:718–723. PMID: 12118109.

12. Hofgartner WT, Thorp M, Ramus MW, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma associated with fundic gland polyps in a patient with attenuated familial adenomatous polyposis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999; 94:2275–2281. PMID: 10445562.

13. Zwick A, Munir M, Ryan CK, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma and dysplasia in fundic gland polyps of a patient with attenuated adenomatous polyposis coli. Gastroenterology. 1997; 113:659–663. PMID: 9247488.

14. Bertoni G, Sassatelli R, Nigrisoli E, et al. Dysplastic changes in gastric fundic gland polyps of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999; 31:192–197. PMID: 10379478.

15. Jung A, Vieth M, Maier O, Stolte M. Fundic gland polyps (Elster's cysts) of the gastric mucosa. A marker for colorectal epithelial neoplasia? Pathol Res Pract. 2002; 198:731–734. PMID: 12530575.

16. Jalving M, Koornstra JJ, Wesseling J, Boezen HM, DE Jong S, Kleibeuker JH. Increased risk of fundic gland polyps during long-term proton pump inhibitor therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006; 24:1341–1348. PMID: 17059515.

17. Camilleri JP, Poter F, Amat C. Gastric mucosal dysplasia: preliminary results of a prospective study of patients followed for periods of up to six years. In : Ming SC, editor. Precursors of Gastric Cancer. New York: Praeger;1984. p. 83–92.

18. de Vries AC, van Grieken NC, Looman CW, et al. Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2008; 134:945–952. PMID: 18395075.

19. Capella C, Solcia E, Sobin LH, Arnold R. Aaltonen LA, Hamilton SR, editors. World Health Organization. International Agency for Research on Cancer. Endocrine tumors of the stomach. Lyon: IARC Press;2000. p. 53–56.

20. Caplin ME, Buscombe JR, Hilson AJ, Jones AL, Watkinson AF, Burroughs AK. Carcinoid tumour. Lancet. 1998; 352:799–805. PMID: 9737302.

21. Rindi G, Luinetti O, Cornaggia M, Capella C, Solcia E. Three subtypes of gastric argyrophil carcinoid and the gastric neuroendocrine carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study. Gastroenterology. 1993; 104:994–1006. PMID: 7681798.

22. Park SJ. Benign and malignant lesion of stomach. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 36(Suppl 1):60–66.

23. Yang CH. Benign and malignant lesion of gastric protruding mass. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2007; 35(Suppl 1):34–44.

24. Chonan A, Mochizuki F, Fujita N, et al. Gastric cancer resembling submucosal tumor. Endoscopic diagnosis of gastric cancer similar to submucosal tumors. Stomach Intest. 1995; 30:777–785.

25. Lee JH. Gastric cancer mimicking submucosal lesions. The 46th Seminar of Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2012. 2012 March 25; Goyang, Korea. Seoul: Korean Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy;p. 85–87.

26. Kim JH, Jeon YC, Lee GW, et al. A case of mucinous gastric adenocarcinoma mimicking submucosal tumor. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2011; 57:120–124. PMID: 21350323.

27. Kim KY, Kim GH, Heo J, Kang DH, Song GA, Cho M. Submucosal tumor-like mucinous gastric adenocarcinoma showing mucin waterfall. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 69(3 Pt 1):564–565. PMID: 19152893.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download