Abstract

Ileal Dieulafoy lesion is an unusual vascular abnormality that can cause gastrointestinal bleeding. It can be associated with massive, life-threatening hemorrhage and requires urgent angiographic intervention or surgery. Ileal Dieulafoy lesion is hard to recognize due to inaccessibility and normal-appearing mucosa. With advances in endoscopy, aggressive diagnostic and therapeutic approaches including enteroscopy have recently been performed for small bowel bleeding. We report two cases of massive ileal Dieulafoy lesion bleeding diagnosed and treated successfully by single balloon enteroscopy with a review of the literature.

Dieulafoy lesion is an aberrant submucosal vessel that lies in close contact with the mucous membrane, which may lead to its exposure, causing massive gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding.1 It is the cause of approximately 6% of upper GI bleeding.2 It is most commonly found in the proximal stomach and especially within 6 cm of the gastroesophageal junction, predominantly on the lesser curvature. However, it can occur anywhere in the GI tract, such as the small bowel.3 Due to difficult access, diagnosis of small bowel bleeding is often delayed; therefore, a multidisciplinary approach is needed to obtain its proper diagnosis and treatment.

We experienced two cases of ileal Dieulafoy lesion bleeding that presented with massive hematochezia and instability of vitals. The two cases were diagnosed and treated successfully using single balloon enteroscopy (SBE) with hemoclips. We discuss the clinical features as well as useful diagnostic and therapeutic modalities of ileal Dieulafoy lesion through a computer-assisted search of the English language literature.

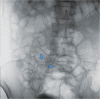

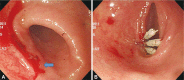

A 47-year-old man was admitted to our hospital for hematochezia of 8 hours. He denied previous medical history as well as taking any medication such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. On initial physical examination, blood pressure was 100/70 mm Hg, and pulse was 102 beats/min. Initial blood hemoglobin level was 10.2 g/dL, but all other values were within normal limits. He underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), but the bleeding focus was not found. We tried to perform colonoscopy but failed due to poor bowel preparation and fresh blood. On the second day of admission, he developed hypovolemic shock due to massive hematochezia, and blood hemoglobin level dropped to 6.2 g/dL. He underwent abdominal computed tomography (CT), which showed contrast media that filled the bowel lumen at the terminal ileum. He then underwent superior mesenteric artery angiography. On the angiography, the contrast media had leaked out of the vessel supplied by a branch of the right ileocolic artery of the superior mesenteric artery, and the bowel lumen around the terminal ileum was filled with contrast media (Fig. 1). However, we failed to control the bleeding, because the artery was too small for embolization treatment. He received transfusions of 10 units of packed red blood cells. While he was prepared for emergency surgery, his vital signs became stabilized, so he underwent colonoscopy. We found fresh blood throughout the entire colon and terminal ileum but could not find the bleeding focus. For small bowel evaluation, we performed SBE with a retrograde approach and found the Dieulafoy lesion on the distal ileum, approximately 20 cm from the ileocecal valve (Fig. 2A). Hemostasis was done successfully using hemoclips (Fig. 2B). For evaluation of other small bowel lesions, we performed capsule endoscopy but could not find any abnormal lesion except the previously placed hemoclips (Fig. 3). He recovered rapidly, with no signs of recurrence.

A 79-year-old woman was admitted due to hematochezia and dizziness. She had obstructive coronary artery disease and took aspirin and an antiplatelet agent. On admission, blood pressure was 127/75 mm Hg, and pulse was 102 beats/min. Blood hemoglobin level was 8.7 g/dL. On the day of admission, she underwent EGD and colonoscopy, but we could not find the bleeding focus. She then underwent abdominal CT, but there was no specific lesion in the GI tract suspicious for bleeding. We recommended enteroscopy for evaluation of the obscure bleeding focus, but she refused because her melena ceased. Vital signs were stabilized, and she was discharged home on the ninth admission day. Six days after discharge, she revisited our hospital due to recurrent fresh hematochezia. At that time, blood pressure dropped to 88/56 mm Hg, and pulse was 107 beats/min. Blood hemoglobin level was 8.3 g/dL. As she had underwent EGD and colonoscopy, we performed SBE with a retrograde approach. We found a fresh blood clot adherent on the mucosa of proximal ileum and, after saline irrigation, we detected the active bleeding focus at a narrow point of normal-appearing mucosa (Fig. 4A). Hemostasis was successfully done using hemoclips (Fig. 4B). She was discharged home and had no evidence of recurrent GI bleeding at her 2 month follow-up visit.

Dieulafoy lesion can be associated with massive, life-threatening hemorrhage and accounts for between 1% and 2% of cases of major GI bleeding.4 Dieulafoy lesion is used to describe the finding of a large submucosal artery, which is otherwise histologically normal, lying in close contact with the mucous membrane. The etiology of this abnormally tortuous submucosal artery is unknown.5 The incidence varies from 0.5% to 14%, depending upon selection criteria.2

As documented above, the diagnosis of Dieulafoy lesion is based upon classical histologic features. However, histologic evaluation is usually unavailable in most case, because recently most vascular lesions have been treated by nonsurgical modalities.6 Endoscopists rely entirely on endoscopic features to make their diagnosis from a critical review of many published articles. Endoscopic criteria for the diagnosis of Dieulafoy lesion are: 1) active arterial spurting or micropulsatile streaming from a minute (less than 3 mm) mucosal defect or through normal-surrounding mucosa; 2) visualization of a protruding vessel with or without active bleeding within a minute mucosal defect or through normal-surrounding mucosa; or 3) a fresh, densely adherent clot with a narrow point of attachment to a minute mucosal defect or to normal-appearing mucosa.7 Although endoscopic features could not be proven to be a true Dieulafoy lesion by the historical criteria mentioned above, the endoscopic finding remains convincing for Dieulafoy lesion.

In one study, the authors classified vascular lesions in the small bowel into the following six groups: 1) type 1a, punctulate erythema (<1 mm), regardless of oozing; 2) type 1b, patchy erythema (a few mm), regardless of oozing; 3) type 2a, punctulate lesions (<1 mm) with pulsatile bleeding; 4) type 2b, pulsatile red protrusion without surrounding venous dilatation; 5) type 3, pulsatile red protrusion with surrounding venous dilatation; and 6) type 4, unclassified lesions. Being different in size from one another, types 1a and 1b were considered angioectasia. Type 2a and 2b were considered Dieulafoy lesion, and type 3 represented an arteriovenous malformation.6 According to that classification, our first case is considered to be type 2b, and the second case is 2a. Angioectasia is a venous/capillary lesion and thus is likely to be treated by endoscopic cauterization. However, Dieulafoy lesion and an arteriovenous malformation may cause arterial bleeding, which require endoscopic treatment with a clip or with laparotomy for large lesions. The authors concluded that this classification would be useful for selecting the hemostatic procedure.6,8

Small bowel bleeding continues to be difficult to visualize directly on routine endoscopy. Therefore, diagnosis of bleeding in the small bowel is often delayed. To localize a source of small bowel bleeding, multidisciplinary approaches such as abdominal CT, angiography, radionuclide scan, and capsule endoscopy is needed. With the development of endoscopy, push enteroscopy is performed to diagnose and treat a bleeding source. Push enteroscopy has two types, SBE and double-balloon enteroscopy (DBE), and two approaches, anterograde (per oral) and retrograde (per anal). In some studies, SBE is as effective as DBE for the appropriate diagnosis and management of obscure GI bleeding cases by identifying a bleeding source and providing a means of treatment in a high percentage of patients.9,10 However, in some studies, DBE had a higher total enteroscopy rate than SBE accompanied by a higher diagnostic yield.11,12 Enteroscopy has a low risk of complications. However, acute pancreatitis after enteroscopy is the most frequent complication and has to be taken into consideration in the written informed consent.13

Several cases of ileal Dieulafoy lesion bleeding have been reported. Most of them were treated surgically and diagnosed with histology.14-16 However, endoscopic treatment will replace surgery in a significant portion of small bowel Dieulafoy lesion cases. Since the widespread availability of endoscopic or angiographic treatment, surgery will play a minor role and often be left as the last therapeutic option for rebleeding lesions or after failed nonsurgical treatment.16

In summary, for the appropriate evaluation of small bowel bleeding, an aggressive multidisciplinary approach, such as radiologic intervention, enteroscopy, and surgery, should be performed. With advances in endoscopic techniques, enteroscopy could play a major role in the diagnosis and treatment of ileal Dieulafoy lesion bleeding.

References

1. Juler GL, Labitzke HG, Lamb R, Allen R. The pathogenesis of Dieulafoy's gastric erosion. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984; 79:195–200. PMID: 6199971.

2. Baettig B, Haecki W, Lammer F, Jost R. Dieulafoy's disease: endoscopic treatment and follow up. Gut. 1993; 34:1418–1421. PMID: 8244112.

3. Blecker D, Bansal M, Zimmerman RL, et al. Dieulafoy's lesion of the small bowel causing massive gastrointestinal bleeding: two case reports and literature review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001; 96:902–905. PMID: 11280574.

4. Baxter M, Aly EH. Dieulafoy’s lesion: current trends in diagnosis and management. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010; 92:548–554. PMID: 20883603.

5. Mikó TL, Thomázy VA. The caliber persistent artery of the stomach: a unifying approach to gastric aneurysm, Dieulafoy’s lesion, and submucosal arterial malformation. Hum Pathol. 1988; 19:914–921. PMID: 3042598.

6. Yano T, Yamamoto H, Sunada K, et al. Endoscopic classification of vascular lesions of the small intestine (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008; 67:169–172. PMID: 18155439.

7. Dy NM, Gostout CJ, Balm RK. Bleeding from the endoscopically-identified Dieulafoy lesion of the proximal small intestine and colon. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995; 90:108–111. PMID: 7801908.

8. Chung IK, Kim EJ, Lee MS, et al. Bleeding Dieulafoy's lesions and the choice of endoscopic method: comparing the hemostatic efficacy of mechanical and injection methods. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000; 52:721–724. PMID: 11115902.

9. Domagk D, Mensink P, Aktas H, et al. Single- vs. double-balloon enteroscopy in small-bowel diagnostics: a randomized multicenter trial. Endoscopy. 2011; 43:472–476. PMID: 21384320.

10. Riccioni ME, Urgesi R, Cianci R, Spada C, Nista EC, Costamagna G. Single-balloon push-and-pull enteroscopy system: does it work? A single-center, 3-year experience. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25:3050–3056. PMID: 21487872.

11. Takano N, Yamada A, Watabe H, et al. Single-balloon versus double-balloon endoscopy for achieving total enteroscopy: a randomized, controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011; 73:734–739. PMID: 21272875.

12. May A, Farber M, Aschmoneit I, et al. Prospective multicenter trial comparing push-and-pull enteroscopy with the single- and double-balloon techniques in patients with small-bowel disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010; 105:575–581. PMID: 20051942.

13. Möschler O, May AD, Müller MK, Ell C. DBE-Studiengruppe Deutschland. Complications in double-balloon-enteroscopy: results of the German DBE register. Z Gastroenterol. 2008; 46:266–270. PMID: 18322881.

14. Fox A, Ravi K, Leeder PC, Britton BJ, Warren BF. Adult small bowel Dieulafoy lesion. Postgrad Med J. 2001; 77:783–784. PMID: 11723319.

15. Shibutani S, Obara H, Ono S, et al. Dieulafoy lesion in the ileum of a child: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:e17–e19. PMID: 21616222.

16. Marangoni G, Cresswell AB, Faraj W, Shaikh H, Bowles MJ. An uncommon cause of life-threatening gastrointestinal bleeding: 2 synchronous Dieulafoy lesions. J Pediatr Surg. 2009; 44:441–443. PMID: 19231553.

Fig. 1

Angiographic finding of superior mesenteric artery. It showed the fine feeding branch from the right ileocolic artery (arrow) and bowel lumen filled with contrast media at the terminal ileum (arrowhead).

Fig. 2

Single-balloon enteroscopic findings. (A) It revealed Dieulafoy lesion on the distal ileum. (B) Hemoclipping was performed on the exposed vessel.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download