Abstract

Background/Aims

We aimed to evaluate whether the advanced techniques have influenced the minor papilla approach.

Methods

We studied the success rate of guide wire insertion by using ordinary techniques and advanced techniques (rendezvous method and precut method) in 30 patients via the minor papilla. We compared the selection of the access routes between before (52 patients) and after (28 patients) the introduction of the Soehendra stent retriever.

Results

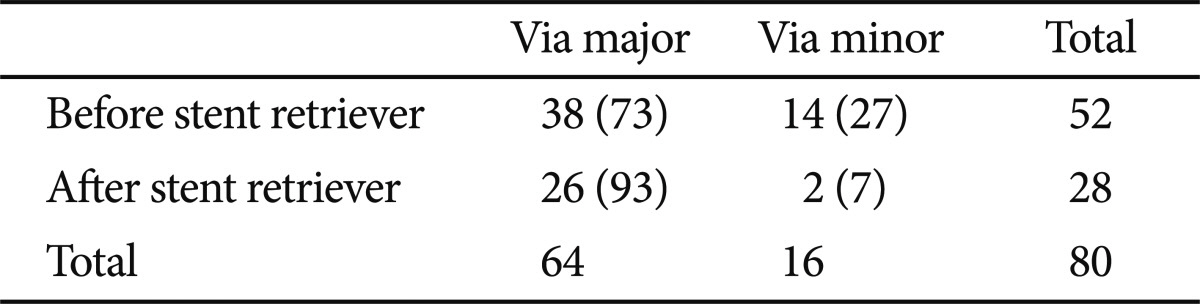

In 19 out of 30 patients (63%), guide wire insertion via the minor papilla could be achieved by using ordinary techniques. In total, the guide wire could be inserted in 27 patients (90%) by using the advanced techniques. Before introduction of the Soehendra stent retriever, the major papilla approach was chosen in 38 cases (73%), and the minor papilla approach in 14 cases (27%). After introduction of the Soehendra stent retriever, the major papilla approach was used in 26 cases (93%) and the minor papilla in 2 cases (7%). The frequency of selecting the minor papilla approach has significantly decreased (p<0.05).

Endoscopic procedures for the main pancreatic duct (MPD) are usually performed via the major duodenal papilla. However, major papilla approaches are sometimes difficult because of various reasons. Many papers have reported that patients with pancreas divisum associated with acute recurrent pancreatitis are the best candidates for endoscopic procedures via the minor papilla.1 When it is difficult to access the MPD through the major papilla, the minor papilla may also be a good alternative for endoscopic interventions in patients without pancreas divisum.2

The indications for endoscopic minor papilla interventions in patients without pancreas divisum used to be extremely limited. The minor papilla approach is often effective for the treatment of pancreatic stones. The result of a Japanese multicenter survey revealed that extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is the standard therapy for the treatment of pancreatic stones.3 Endoscopic treatment for pancreatic stones is regarded as adjunctive therapy for ESWL. Fragments of pancreatic stones during ESWL treatment are sometimes impacted on the orifice or stricture of MPD. Therefore, it is recommended that endoscopists who are engaged in ESWL for pancreatic stones should acquire the technique of pancreatic stenting in order to remove the impacted stone fragments in emergency cases. An approach via the minor papilla may be the only alternative when the approach via the major papilla is not possible because of the presence of MPD strictures, stones, or distortion in the course of the MPD.

With refinements in endoscopic instruments and procedures, the number of reports of endoscopic treatment via the minor papilla is increasing.4 The use of advanced techniques such as the rendezvous technique has been increasing. Recently, the insertion technique for passing through strictures of the MPD has being improved by using the Soehendra stent retriever.

The present study evaluated whether these new, advanced techniques have contributed to the improvement of the success rate for guide wire insertion via the minor papilla and influenced the selection between approach routes in the endoscopic treatments for pancreatic stones.

We enrolled 30 cases in which we tried to insert the guide wire through the minor papilla in this study. These 30 cases consisted of 3 groups. The first group consisted of 11 patients with pancreas divisum. The second group consisted of 17 patients who received pancreatic stone therapy. The last group consisted of 2 patients with intraductal pancreatic mucinous neoplasm and hemosuccus pancreatitis.

We have performed ESWL treatments in 184 patients with pancreatic stones from January 1990 to April 2012. The endoscopic approach, used as an adjunctive therapy for ESWL, was performed in 80 patients. Fifty-two patients were treated before introduction of the Soehendra stent retriever and 28 patients after its introduction.

We used an electroduodenoscope, JF-240, 260, TJF, JF-V260 (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan). Fine guide wires GW (0.014, 0.018, 0.021, and 0.025 inch) (Jagwire; Microvasive Endoscopy, Boston Scientific Co., Natick, MA, USA) or (Revowave; Piolax Medical Devices Inc., Yokohama, Japan) were employed. A cannula tapered at the tip (PR-131/132Q) and various metal-tipped cannulas (ERCP-1-HKC, PR-131Q, etc.) were used.

At first, we started the ordinary minor papilla approach by using the above-mentioned cannulas. If we could not insert the guide wire using the ordinary technique, we used the following 2 advanced techniques.

The first technique is the rendezvous method.2 A 0.025-inch guide wire was advanced and withdrawn with multiple changes in its position via the major papilla. Eventually, the tip of the guide wire passed antegrade into the accessory pancreatic duct. The guide wire was intentionally advanced through the minor papilla and into the duodenal lumen, where it was visualized endoscopically. Then, the catheter was removed, and the tip of the guide wire exiting the minor papilla was grasped with a basket catheter and withdrawn via the accessory channel of the duodenoscope. Once the guide wire was retracted from the channel, a catheter was advanced over it and inserted deep into the accessory duct via the minor papilla. After removing the guide wire, which was inserted through the major papilla, another guide wire was introduced through the catheter inserted via the minor papilla and advanced into the MPD. Thus, access was secured for subsequent minor papilla papillotomy and further endoscopic interventions. The second advanced technique is the precut method using a needle knife.

We used these 2 techniques in cases in which the contrast medium could not be injected through the minor papilla by using a cannula tapered at the tip or metal-tipped cannulas.

Even after successful guide wire insertion, the pancreatic stent can often not be advanced due to the presence of strictures, impacted stones, or distortion of the course of the MPD. We had used the Soehendra dilation catheter 4 to 7 Fr to insert pancreatic stents. Since March 2009, we employed the Soehendra stent retriever when the Soehendra dilation catheter 4 to 7 Fr could not pass the stricture or the impacted stones.

We studied whether the 2 advanced techniques could contribute to the improvement of the success rate for guide wire insertion via the minor duodenal papilla. We evaluated the success rate of the location of the minor papilla, guide wire insertion by using ordinary techniques, and guide wire insertion by using advanced techniques as well as the final total achievements.

In 28 (93%) of 30 patients, we could locate the position of the minor papilla (Fig. 1A). In 24 patients (85.7%), a pancreatogram could be obtained via the minor papilla by using ordinary techniques (tapered at the tip and metal-tipped cannulas). In 19 patients (63%), guide wire insertion could be achieved via the minor papilla.

In 11 patients in whom guide wire insertion failed, the rendezvous method was used in 9 patients without pancreas divisum and the precut method was used in 2 patients with pancreas divisum (Fig. 1B). In 6 of the 9 patients without pancreas divisum, the guide wire could be inserted by using the rendezvous technique. In both patients with pancreas divisum, the guide wire could be inserted by using the precut method. In total, in 27 (90%) of 30 patients, the guide wire could be inserted by using ordinary and advanced techniques.

In all 10 patients in whom the Soehendra dilation catheter could not pass the stricture or impacted stones, the Soehendra stent retriever could be advanced easily at the first attempt in every case (Fig. 2).

Before introduction of the Soehendra stent retriever, the major papilla approach was chosen in 38 cases (73%) and the minor papilla approach in 14 cases (27%)(Table 1). After introduction of the Soehendra stent retriever, the major papilla approach was used in 26 cases (93%) and the minor papilla in 2 cases (7%)(Table 1). In 2 cases in which the minor papilla approach was used, one case was due to pancreas divisum and the other case was due to the tight impaction of a huge stone in the Wirsung duct.

The frequency of selecting the minor papilla approach has significantly decreased after introduction of the Soehendra stent retriever (p<0.05).

Due to the small size of the orifice of the minor papilla compared with that of the major papilla, it is difficult to inject contrast medium into the MPD. However, there are 2 major conditions in which the minor papilla approach is indicated. First, patients with pancreas divisum associated with acute recurrent pancreatitis are the best candidates for endoscopic procedures, including minor papilla sphincterotomy and stenting.1 Second, in patients with presence of strictures, stones, or distortion of the course of the MPD, an approach via the minor papilla may be the only alternative.2

Results of the rendezvous method have been reported.2 In 6 of 9 patients of this study, the guide wire could be advanced using the rendezvous method. In 2 out of 3 failed cases, the guide wire could not reach the minor papilla. In the other case, the guide wire could not be withdrawn through the accessory channel of the duodenoscope because of strong resistance. Withdrawal of the guide wire through the accessory channel of the duodenoscope should be done carefully in order not to injure the pancreas.

In both patients with pancreas divisum in this study, the guide wire could be inserted by using the precut method. If deep cannulation or opacification via the minor papilla was unsuccessful, a needle knife was used to puncture or incise the minor papilla. In addition, a needle knife has also been used to aid in the performance of minor papilla sphincterotomy. Both rendezvous technique and direct minor papilla approach require high levels of expertise and experience.2

Within the past few years, ESWL has been used successfully to treat patients with pancreatic stones,5,6 and combination therapy using ESWL and an endoscopic approach has been recommended for patients with chronic pancreatitis.3 Adjuvant endoscopic procedures have been used to increase the efficacy of ESWL. Such measures include stone retrieval with a basket catheter after endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy and insertion of a plastic stent into the pancreatic duct. With combination therapy, the complete stone clearance rate has been reported to range from 72.6% to 100%.3,5-7 In addition, stricture of the MPD is one of the important etiologic factors in calculus recurrence.6 Pancreatic stenting or balloon dilatation is often performed to prevent calculus recurrence in patients with strictures of the MPD. However, Brand et al.8 found that strictures did not adversely affect the outcome.

Acute pancreatitis was the most common complication associated with ESWL for pancreatic stones and was treated successfully by endoscopic removal of impacted stone fragments. Physicians performing ESWL should also acquire the technique of interventional endoscopy for pancreatic stones. We have reported a case of purulent pancreatic ductitis successfully treated by endoscopic stenting for the first time.9 We have experienced several similar cases that were caused by obstruction of the pancreatic stent and impaction of pancreatic stone fragments at the orifice of the MPD. All these cases showed abdominal pain, high fever, and occasionally disseminated intravascular coagulation, regardless of antibiotics therapy. Such cases are difficult to be diagnosed because abdominal computed tomography does not show findings suggesting acute pancreatitis, e.g., pancreatic enlargement and inflammatory changes in and around the pancreas, except severe dilation of the MPD. We have called this condition "acute obstructive suppurative pancreatitis (AOSP)" in reference to "acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis." Other authors have published the same condition.10,11 In patients with this condition, pancreatic stenting should be performed immediately after the diagnosis of AOSP is established. However, when the guide wire and/or pancreatic stent cannot reach the deep MPD via the major papilla because of the presence of strictures, stones, or distortion of the course of the MPD, the minor papilla approach may be the only alternative.

The Soehendra stent retriever has been used for the endoscopic retrieval of migrated biliary and pancreatic plastic stents.12 The Soehendra stent retriever has been also used for other purposes. Tight pancreatic and bile duct strictures can be dilated successfully with the Soehendra stent retriever and the procedure is of low risk.13,14 The 7 Fr Soehendra stent retriever could be inserted easily after failed insertion of the 4 to 7 Fr Soehendra dilating catheter in all 10 consecutive cases of this study with no complications.

Our study showed that introduction of advanced techniques such as the rendezvous method in cases without pancreas divisum and the precut method in cases with pancreas divisum increased the success rate of the minor papilla approach from 63% to 90%. Introduction of the Soehendra stent retriever for cases with pancreatic stones significantly decreased the rate of selecting the minor papilla approach after failure of the major papilla approach. We summarized our present strategy for pancreatic stenting in Fig. 3. Lastly, we hope that our strategy can be improved in the future with the development of new techniques.

References

1. Ertan A. Long-term results after endoscopic pancreatic stent placement without pancreatic papillotomy in acute recurrent pancreatitis due to pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000; 52:9–14. PMID: 10882955.

2. Song MH, Kim MH, Lee SK, et al. Endoscopic minor papilla interventions in patients without pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004; 59:901–905. PMID: 15173812.

3. Inui K, Tazuma S, Yamaguchi T, et al. Treatment of pancreatic stones with extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy: results of a multicenter survey. Pancreas. 2005; 30:26–30. PMID: 15632696.

4. Inui K, Yoshino J, Miyoshi H. Endoscopic approach via the minor duodenal papilla. Dig Surg. 2010; 27:153–156. PMID: 20551663.

5. Ohara H, Hoshino M, Hayakawa T, et al. Single application extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy is the first choice for patients with pancreatic duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996; 91:1388–1394. PMID: 8678001.

6. Nakamura Y, Inui K, Nakazawa S, et al. Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy for treatment of patients with pancreatic ductal strictures. Tan Sui. 1997; 18:1175–1179.

7. Okumura F, Ohara H, Nakazawa T, et al. Indications for and limitations of extracorpareal shhock wave lithotripsy and endoscopic therapy for the main pancreatic duct stones associated with chronic pancreatitis. Suizo. 2009; 24:56–61.

8. Brand B, Kahl M, Sidhu S, et al. Prospective evaluation of morphology, function, and quality of life after extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy and endoscopic treatment of chronic calcific pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000; 95:3428–3438. PMID: 11151873.

9. Aoki S, Okayama Y, Hayashi K, et al. A case of purulent pancreatic ductitis successfully treated by endoscopic stenting. Dig Endosc. 2000; 12:341–344.

10. Tajima Y, Kuroki T, Susumu S, et al. Acute suppuration of the pancreatic duct associated with pancreatic ductal obstruction due to pancreas carcinoma. Pancreas. 2006; 33:195–197. PMID: 16868487.

11. Fujimori N, Igarashi H, Ito T. Acute obstructive suppurative pancreatic ductitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011; 9:A28. PMID: 21421076.

12. Sakai Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Ishihara T, et al. Cholangiopancreatography troubleshooting: the usefulness of endoscopic retrieval of migrated biliary and pancreatic stents. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009; 8:632–637. PMID: 20007082.

13. Brand B, Thonke F, Obytz S, et al. Stent retriever for dilation of pancreatic and bile duct strictures. Endoscopy. 1999; 31:142–145. PMID: 10223363.

14. Ziebert JJ, DiSario JA. Dilation of refractory pancreatic duct strictures: the turn of the screw. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999; 49:632–635. PMID: 10228264.

Fig. 1

(A) Guide wire insertion via minor papilla by ordinary approach.

(B) Guide wire insertion via minor papilla by advanced approach.

Fig. 2

Soehendra stent retriever. (A) A guide wire successfully passed an impacted stone at the head of the pancreas. (B) The Soehendra dilation catheter (4 to 7 Fr) could not pass the stone. (C) The Soehendra stent retriever (7 Fr) could pass the stone easily. (D) A pancreatic stent (7 Fr) could be inserted.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download