Abstract

Pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) is known to be associated with antibiotic treatment, but is not commonly related to antitubercular (anti-TB) agent, rifampin. PMC is frequently localized to rectum and sigmoid colon, which can be diagnosed with sigmoidoscopy. We report a case of rifampin-induced PMC with rectosigmoid sparing in a pulmonary tuberculosis patient. An 81-year-old man using anti-TB agents was admitted with a 30-day history of severe diarrhea and general weakness. On colonoscopy, nonspecific findings such as mucosal edema and erosion were found in sigmoid colon, whereas multiple yellowish plaques were confined to cecal mucosa only. Biopsy specimen of the cecum was compatible with PMC. Metronidazole was started orally, and the anti-TB medications excluding rifampin were readministerred. His symptoms remarkably improved within a few days without recurrence. Awareness of rectosigmoid sparing PMC in patients who develop diarrhea during anti-TB treatment should encourage early total colonoscopy.

Pseudomembranous colitis (PMC) is a severe form of Clostridium difficile infection which is usually confined to rectum and sigmoid colon but sometimes involves ascending colon, making sigmoidoscopy sufficient to detect PMC.1 It is commonly associated with the antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, clindamycin, cephalosporins, and penicillins.2 In addition, antitubercular (anti-TB) agent rifampin, which has broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, is also known to be an uncommon cause of PMC.3,4 Like most of the usual PMC, all of the reported cases of rifampin-induced PMC were also observed in rectosigmoid colon except for one.5 We present a case of rectosigmoid sparing PMC in a patient taking anti-TB agents.

An 81-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with a 30 day history of watery diarrhea 10 times per day and general weakness. He was diagnosed as pulmonary tuberculosis 45 days before admission and was on standard anti-TB medications, rifampin (600 mg/day), isoniazid (300 mg/day), ethambutol (800 mg/day), and pyrazinamide (1,500 mg/day) since then. On admission, he stopped taking all anti-TB medications for 2 weeks after 30 days on the regimen. Vital signs were stable and abdominal physical examination did not show abnormal findings except for the hyperactive bowel sounds. Laboratory findings showed increased leukocyte counts (white blood cell, 21,200/mm3; neutrophil, 90.7%) and increased inflammatory markers such as erythrocyte sediment rate (75 mm/hr; normal, 0-9 mm/hr) and C-reactive protein (5.14 mg/dL; normal, 0.02-0.3 mg/dL).

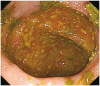

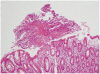

The sputum acid-fast bacteria stain was positive and the chest X-ray showed patchy consolidation in the right lung field. Since watery diarrhea started after 15 days of anti-TB medications and continued for 30 days, anti-TB agents induced PMC was suspected before C. difficile toxin result was obtained. Therefore, sigmoidoscopy was initially planned. When sigmoidoscopic examination was performed with a colonoscope, the sigmoid colon revealed edematous and erosive mucosa only (Fig. 1). Due to diarrhea-induced bowel cleansing, the colonoscope was able to be advanced proximally into the terminal ileum, which showed multiple yellowish plaques only in the cecal mucosa (Fig. 2). Biopsy specimen of the cecum revealed disruption of surface epithelium with an overlying mushroom-shaped pseudomembrane which was compatible with the findings of PMC (Fig. 3). After colonoscopy, the stool assay for C. difficile toxin came out to be positive but stool culture for C.difficile was negative. Oral metronidazole (1,500 mg/day) was started and anti-TB agents excluding rifampin were readministerd 2 days after the initiation of metronidazole. His symptoms improved remarkably the day after taking the medications and did not recur since then.

PMC is a characteristic manifestation of full blown C. difficile infection, which is acquired almost exclusively in association with the use of antimicrobials and the consequent disruption of the normal colonic flora. Various antibiotics, including lincomycin, clindamycin, and β-lactam compunds are well known causative agents of PMC. On the other hand, anti-TB agents are uncommon cause of PMC and a few cases of anti-TB agents-related PMC have been described since the 1980s.6-9 Although it is still controversial whether rifampin can be a causative agent, rifampin has been postulated to be one of the causes because it has antibacterial activity on a broad spectrum of bacteria whereas isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol do not have antibacterial activity to disturb the normal intestinal flora.10 Besides the broad spectrum of antibacterial activity, frequent isolation of rifampin-resistant toxigenic C. difficile also implies that rifampin could be the causative agent.11,12

In the present case, given the temporal relationship between anti-TB medications and the onset of symptoms, it is suspected that PMC was associated with anti-TB agents. Additionally, the patient's symptoms did not recur after rechallenging the rest of anti-TB agents except for rifampin, which demonstrates that rifampin caused PMC in our case.

The identified risk factors for PMC include advanced age, immunocompromised state, hospitalization, and procedures or medications that alter the intestinal motility or flora.13 The median age of rifampin-induced PMC was 59.5 years, which is younger than that of usual PMC patients.4 Our patient was older than most of the reported cases, although he did not have other risk factors. Rifampin-induced PMC was also associated with moderate-to-severe liver dysfunction.7,10,14 It is thought that liver dysfunction results in reduced biliary excretion of rifampin, which causes high concentration of serum levels and/or low intestinal rifampin levels.8,14

The clinical presentations of PMC include diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, and leukocytosis. Most patients develop PMC after 5 to 10 days of antibiotic treatment. However, in rifampin-associated PMC, the median latency period was 4 weeks, longer than the commonly known causes of PMC,4 which reflects that rifampin may have less capacity to perturb the intestinal bacterial flora than other antibiotics such as β-lactam compounds and clindamycin.10 The latency of our patient's clinical symptom was about 2 weeks, which was shorter than that of previously reported cases.4,15

The confirmative diagnosis of PMC is either positive stool culture or positive stool toxin assay for C. difficile with clinical data. However, sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy or abdominal computed tomography scan can provide useful diagnostic information. PMC is commonly localized to the rectum and sigmoid colon. Thus, sigmoidoscopy is usually sufficient to detect typical findings of PMC such as the pseudomembrane. However, there are reports of rectal or rectosigmoid sparing PMC occuring in as many as 23% to 69% of patients.16,17 Normal mucosal appearance or nonspecific proctosigmoiditis may be the sigmoidoscopic finding but pseudomembrane can be found in ascending colon as occurred in our case. Therefore, total colonoscopy should be performed to confirm the diagnosis of PMC, if sigmoidoscopy is inconclusive. The test for resistant strain of C. difficile is needed for the investigation of causative agent of PMC in a patient suspected to have rifampin-associated PMC. In our case, however, the test for rifampin resistance could not be performed due to negative stool culture of C. difficile.

Once PMC is diagnosed, it is usually treated with oral metronidazole 500 mg t.i.d. or 250 mg q.i.d. for 10 days.18 Besides antibiotic therapy, restoration of beneficial intestinal flora with probiotics may suppress the abnormal overgrowth of C. difficile and thus ameliorate the course of the disease. In our case, watery diarrhea was disappeared with metronidazole therapy, although the discontinuation of all anti-TB medications did not affect his symptom. However, it was recently reported in Korea that anti-TB agents induced PMC was treated with maintenance of the anti-TB medications and the addition of both oral metronidazole and probiotics.15

In conclusion, our case reinforces the concept that rifampin can be one of the causes of PMC and reveals that rifampin-induced PMC can be presented as a localized disease with rectosigmoid sparing. Thus, total colonoscopy is needed for the differential diagnosis in patients with severe diarrhea developing during or after anti-TB treatment, if sigmoidoscopy is not confirmative.

References

1. Rubesin SE, Levine MS, Glick SN, Herlinger H, Laufer I. Pseudomembranous colitis with rectosigmoid sparing on barium studies. Radiology. 1989; 170:811–813. PMID: 2916034.

2. Bartlett JG. Clinical practice. Antibiotic-associated diarrhea. N Engl J Med. 2002; 346:334–339. PMID: 11821511.

3. Jung SW, Jeon SW, Do BH, et al. Clinical aspects of rifampicin-associated pseudomembranous colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007; 41:38–40. PMID: 17198063.

4. Chen TC, Lu PL, Lin WR, Lin CY, Wu JY, Chen YH. Rifampin-associated pseudomembranous colitis. Am J Med Sci. 2009; 338:156–158. PMID: 19561451.

5. Akbar DH, Al-Shehri HZ, Al-Huzali AM, Falatah HI. A case of rifampicin induced pseudomembraneous colitis. Saudi Med J. 2003; 24:1391–1393. PMID: 14710291.

6. Moriarty HJ, Scobie BA. Pseudomembranous colitis in a patient on rifampicin and ethambutol. N Z Med J. 1980; 91:294–295. PMID: 6930008.

7. Klaui H, Leuenberger P. Pseudomembranous colitis due to rifampicin. Lancet. 1981; 2:1294. PMID: 6118708.

8. George RH. Pseudomembranous colitis probably due to rifampicin. Lancet. 1980; 1:1304. PMID: 6104109.

9. Park JY, Kim JS, Jeung SJ, Kim MS, Kim SC. A case of pseudomembranous colitis associated with rifampin. Korean J Intern Med. 2004; 19:261–265. PMID: 15683116.

10. Nakajima A, Yajima S, Shirakura T, et al. Rifampicin-associated pseudomembranous colitis. J Gastroenterol. 2000; 35:299–303. PMID: 10777161.

11. Barbut F, Decrbu D, Burghoffer B, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibilities and serogroups of clinical strains of Clostridium difficile isolated in France in 1991 and 1997. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999; 43:2607–2611. PMID: 10543736.

12. Bendle JS, James PA, Bennett PM, Avison MB, Macgowan AP, Al-Shafi KM. Resistance determinants in strains of Clostridium difficile from two geographically distinct populations. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2004; 24:619–621. PMID: 15555889.

13. LaHatte LJ, Schuman BM. Haubrich WS, Schaffner F, Berk JE, editors. Antibiotic-associated injury to the gut. Bockus Gastroenterology. 1995. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;p. 1657–1671.

14. Fournier G, Orgiazzi J, Lenoir B, Dechavanne M. Pseudomembranous colitis probably due to rifampicin. Lancet. 1980; 1:101. PMID: 6101404.

15. Woo ML, Cho JH, Kim JH, et al. Anti-tuberculosis agents induced Pseudomembranous colitis treated with maintaining anti-tuberculosis drugs. Korean J Gastrointest Endosc. 2009; 38:47–51.

16. Burbige EJ, Radigan JJ. Antibiotic-associated colitis with normal-appearing rectum. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981; 24:198–200. PMID: 7227136.

17. Tedesco FJ, Corless JK, Brownstein RE. Rectal sparing in antibiotic-associated pseudomembranous colitis: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1982; 83:1259–1260. PMID: 7129030.

18. Gonenne J, Pardi DS. Clostridium difficile: an update. Compr Ther. 2004; 30:134–140. PMID: 15793312.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download