Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to analyze the results of an immediate and mid-term angiographic and clinical follow-up of endovascular treatment for paraclinoid aneurysms.

Materials and Methods

From January 2002 to December 2012, a total of 113 consecutive patients (mean age: 56.2 years) with 116 paraclinoid saccular aneurysms (ruptured or unruptured) were treated with endovascular coiling procedures. Clinical and angiographic outcomes were retrospectively evaluated.

Results

Ninety-three patients (82.3%) were female. The mean size of the aneurysm was 5.5 mm, and 101 aneurysms (87.1%) had a wide neck. Immediate catheter angiography showed complete occlusion in 40 aneurysms (34.5%), remnant sac in 51 (43.9%), and remnant neck in 25 (21.6%). Follow-up angiographic studies were performed on 80 aneurysms (69%) at a mean period of 20.4 months. Compared with immediate angiographic results, follow-up angiograms showed no change in 38 aneurysms, improvement in 37 (Fig. 2), and recanalization in 5. There were 6 procedure-related complications (5.2%), with permanent morbidity in one patient.

The segment of the internal carotid artery between the roof of the cavernous sinus and the origin of the posterior communicating artery has been called the paraclinoid segment [1]. This segment also has been called the C2 segment, the ventral internal carotid artery segment, the carotid-ophthalmic segment, and the ophthalmic segment [2]. Surgical clipping of the aneurysms in this location remains a challenge due to obstructing the anterior clinoid process and the close relationships with the cavernous sinus, carotid siphon, and optic nerve [3]. During the open surgical procedure, exposure of the cervical carotid artery and anterior clinoidectomy are often required. These maneuvers lead to a higher surgical morbidity and mortality [3, 4].

For these reasons, paraclinoid aneurysms are frequently referred for endovascular treatment [5, 6]. The aim of this study was to retrospectively evaluate our results of endovascular treatment for paraclinoid aneurysms.

Between January 2002 and December 2012, 116 paraclinoid saccular aneurysms in 113 patients with endovascular treatment were treated at our institution. We retrospectively reviewed the medical records and radiologic data for these 113 patients.

We classified aneurysms according to location, size and neck type. According to the location in the internal carotid artery, we classified 116 aneurysms into 1) superior hypophyseal artery type, 2) ventral wall type, 3) dorsal wall type, and 4) ophthalmic artery origin type [7, 8]. Size of fundus and neck of aneurysm were measured at the point of maximum length or width. Size of fundus was classified as small (< 7 mm) or large (≥ 7 mm). A wide neck was defined as a dome to neck ratio of less than 2 or a neck that was 4 mm or wider as measured on angiograms. The dome to neck ratio was the ratio of maximum sac diameter to neck diameter. Most endovascular procedures were performed under general anesthesia, except in some cases of ruptured aneurysms. After placement of the femoral sheath, systemic heparinization was started (3000-5000IU of intravenous heparin in proportion to the weight and 1000IU per hour) except for ruptured aneurysms.

We assessed the results of coil embolization on posttreatment angiography using the Raymond classification: 1) complete, 2) remnant neck, and 3) remnant sac. Angiographic follow-up was performed with magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) or catheter angiography. Recanalization was defined as an increase in the contrast opacification within the neck or sack that was greater than the initial obliteration and re-treatment was considered. Clinical outcomes were assessed at the time of discharge using the modified Rankin scale (mRS) score. Favorable outcome was defined as a mRS ≤ 2.

The mean age was 56.2 years. The majority of the patients (93 patients; 82.3%) were women. 22 patients had multiple aneurysms. Among 116 aneurysms, 10 aneurysms were ruptured. The mean size of the aneurysms was 5.52 mm. Most of the aneurysms were less than 7 mm (n=90:77.6%) and had a wide neck (n=101:87.1%). Aneurysms were located in the superior hypophyseal artery (n=80:69%), ventral wall (n=24:20.7%), dorsal wall (n=5:4.3%) and ophthalmic artery origin (n=7:6%).

Aneurysms were treated with the single catheter technique (n=57), stent-assisted technique (n=36), balloon-assisted technique (n=17), double catheter technique (n=4) and stent placement only (n=2). A number of different stents or balloons were used; Neuroform stent (Boston Scientific Neurovascular, Fremont, CA, USA) in 10 patients, Enterprise stent (Cordis, Neurovascular, Miami, FL, USA) in 20 patients and Solitaire stent (ev3 Inc., Irvine, CA, USA) in 6 patients. 16 patients used the HyperGlide balloon system (ev3 Inc., Irvine, CA, USA), and one patient used the Equinox balloon (Micro Therapeutics Inc., Irvine, CA, USA).

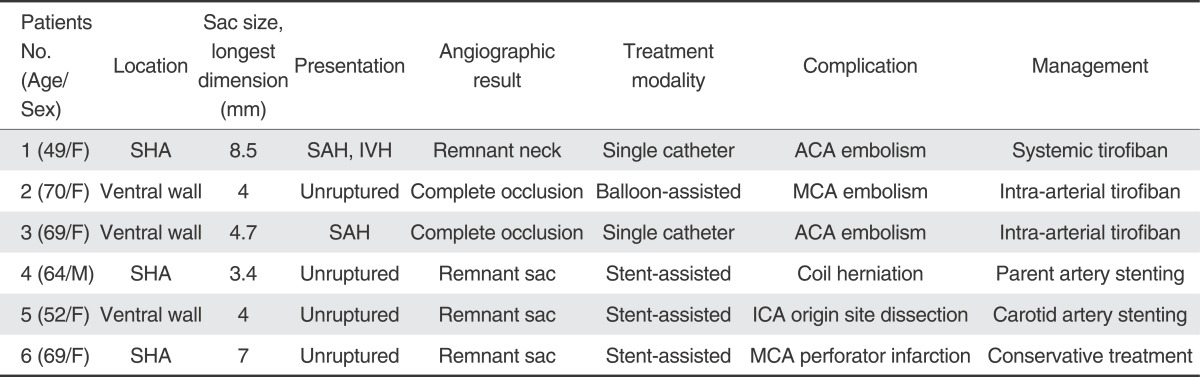

Immediate angiographic results showed complete occlusion in 40 aneurysms (34.5%), neck remnant in 25 aneurysms (21.6%) and remnant sac in 51 aneurysms (43.9%). There were six (5.2%) procedurerelated complications (Table 1, Fig. 1), with one morbidity at discharge. A 69-year-old woman who developed acute infarction in left corona radiata after the treatment discharged with right hemiparesis. No cases of peri-procedural mortality occurred. At the time of discharge, 109 patients (96.5%) had a favorable outcome and 4 patients (3.5%) had an unfavorable outcome. Of the patients with unruptured aneurysms, only 5 patients developed new neurological sequelae. Of the patients with ruptured aneurysms, 3 patients had unfavorable outcomes.

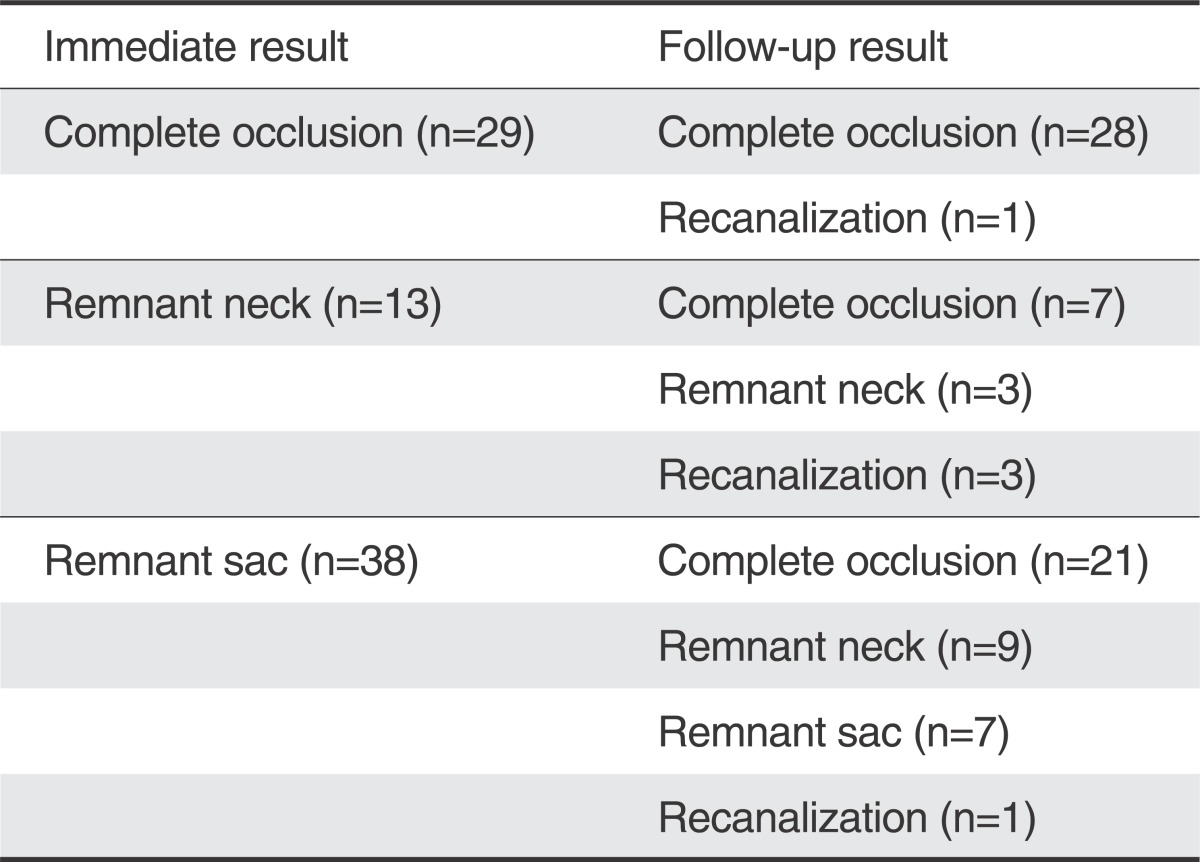

Angiographic follow-up was available in 80 patients (69%), with an average follow-up period of 20.4 months (range 6-89 months). MRA was performed in 46 patients and catheter angiography in 34 patients. Follow-up angiographic results in these 80 patients were described in Table 2. Follow-up angiographic studies showed complete occlusion in 56 aneurysms (70%), remnant neck in 12 (15%) and remnant sac in 12 (15%). Compared with immediate angiographic results, follow-up angiograms showed no change in 38 aneurysms, improvement in 37 (Fig. 2), and recanalization in 5. Four of 5 recanalized aneurysms were retreated by an endovascular approach (Fig. 3), and one aneurysm was treated conservatively. No case of rebleeding was observed during the follow-up period in these 80 patients.

Paraclinoid aneuryms account for approximately 1.5-8% of all intracranial aneurysms, and there is a striking predominance of females. These aneurysms have a high association with multiple aneurysms and significant numbers are found incidentally [9]. In our cases, the majority of patients were women (82.3%), 22 patients had multiple aneurysms, and most of the aneurysms were unruptured. There are various classifications to subdivide paraclinoid aneurysms. We modified the classification by Barami et al. for simple subdivision [8]. In our case series, most of the aneurysms were classified into the superior hypophyseal artery type (69%). Subclassification of paraclinoid aneuryms is not so important for endovascular treatment as much as it is in surgical clipping. For the endovascular approach, the size of the aneurismal neck is more important, because aneurysms with a wide neck need a more complex endovascular treatment strategy. Most of the aneurysms (87.1%) had a wide neck, and many cases were treated by balloon or stent assistance techniques in our study.

Our results have demonstrated high rates of successful coil embolization with low morbidity; procedure-related complications happened in 6 cases out of 116 embolization procedures (5.2%). Among them, procedure-related permanent morbidity was observed in only one case (0.86%). There was a report of a high successful rate for endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. Park et al. reported endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms in 73 patients. Immediate angiographic outcomes demonstrated complete occlusion in 72.6%, near-complete occlusion in 8.2% and partial occlusion in 19.2% [5].

For open surgical clipping, Meyer et al. reviewed their surgical experience with clinoid segment carotid artery aneurysms unsuitable for endovascular treatment. In their series, 37 aneurysms underwent direct surgical clipping, two underwent trapping with bypass and one underwent trapping without bypass. The complication rate was 10%, with one major stroke, two minor strokes and one brain abscess [10]. Yadla et al. reviewed open, endovascular or combined treatment of unruptured carotid-ophthalmic aneurysms in 170 cases. The major complication rate of an endovascular approach alone was 1.4%, and 26.1% with the open microsurgical procedure. And, they concluded that endovascular treatment of carotid-ophthalmic aneurysms with modern endovascular techniques can be performed safely and efficaciously in an elective setting [3]. Endovascular treatment also has complications. Wang et al. reported 6 (4.3%) procedural complications during endovascular treatment of 137 paraclinoid aneurysms. But, there was no permanent morbidity or mortality [1]. Ross et al. reported that vessel or aneurysm perforation occurred in 11 cases and led to adverse outcome in 3 (3%). Thromboembolic complications were felt to cause cerebral infarction in 8 cases (6%). The risk of vessel/aneurysm rupture or thromboembolic stroke was greater in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Eight attempts to coil (6%) were initially unsuccessful. Two of these were later successfully coiled and others had surgery [11]. Park et al. reported that procedural morbidity and mortality rates were highest in ruptured aneurysms and lowest in unruptured aneurysms. No procedural mortality occurred with re-treated aneurysms. The main cause of morbidity and mortality was thromboembolism [12].

In our cases, 37 of 51 that showed incomplete occlusion on the immediate angiographic result, showed improvement in follow-up studies. It is of note that most of them were treated with stent-assisted coil embolization. Wang et al reported that the angiographic recurrence rate of endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms was 12.5%. And the stent assisted coiling technique was effective for the treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. And they also showed that small paraclinoid aneurysms (≤ 10 mm) were suitable for endovascular treatment, which was associated with a low recurrence rate [1]. Ogilvy et al. compared stent-assisted coiling versus coiling alone of paraclinoid aneurysms. The overall effectiveness of stent-assisted coiling was comparable to that of bare coiling [13]. Limitations of the present study include the small number of patients and an inadequate follow-up. Further follow-up and more experience are necessary to determine the long-term efficacy of the treatment.

In conclusion, our study suggests that the properly-selected patients with paraclinoid aneurysms can be successfully treated by endovascular means.

References

1. Wang Y, Li Y, Jiang C, Jiang F, Meng H, Siddiqui AH, et al. Endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms:142 aneurysms in one centre. J Neurointerv Surg. 2013; 5:552–556. PMID: 23087381.

2. Hoh BL, Carter BS, Budzik RF, Putman CM, Ogilvy CS. Results after surgical and endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms by a combined neurovascular team. Neurosurgery. 2001; 48:78–89. PMID: 11152364.

3. Yadla S, Campbell PG, Grobelny B, Jallo J, Gonzalez LF, Rosenwasser RH, et al. Open and endovascular treatment of unruptured carotid-ophthalmic aneurysms: clinical and radiographic outcomes. Neurosurgery. 2011; 68:1434–1443. PMID: 21273934.

4. Sun Y, Li Y, Li AM. Endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol. 2011; 17:425–430. PMID: 22192545.

5. Park HK, Horowitz M, Jungreis C, Genevro J, Koebbbe C, Levy E, et al. Endovascular treatment of paraclinoid aneurysms: experience with 73 patients. Neurosurgery. 2003; 53:14–23. PMID: 12823869.

6. Roy D, Raymond J, Bouthillier A, Bojanowski MW, Moumdjian R, L'Espérance G. Endovascular treatment of ophthalmic segment aneurysms with Guglielmi detachable coils. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997; 18:1207–1215. PMID: 9282843.

7. Day AL. Aneurysms of the ophthalmic segment. A clinical and anatomical analysis. J Neurosurg. 1990; 72:677–691. PMID: 2324793.

8. Barami K, Hernandez VS, Diaz FG, Guthiconda M. Paraclinoid Carotid Aneurysms: Surgical Management, Complications, and Outcome Based on a New Classification Scheme. Skull Base. 2003; 13:31–41. PMID: 15912157.

9. Jin SC, Kwon do H, Ahn JS, Kwun BD, Song Y, Choi CG. Clinical and radiogical outcomes of endovascular detachable coil embolization in paraclinoid aneurysms : a 10-year experience. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2009; 45:5–10. PMID: 19242564.

10. Meyer FB, Friedman JA, Nichols DA, et al. Surgical repair of clinoidal segment carotid artery aneurysms unsuitable for endovascular treatment. Neurosurgery. 2001; 48:476–485. PMID: 11270536.

11. Ross IB, Dhillon GS. Complications of endovascular treatment of cerebral aneurysms. Surg Neurol. 2005; 64:12–18. PMID: 15993171.

12. Park HK, Horowitz M, Jungreis C, Genevro J, Koebbbe C, Levy E, et al. Periprocedural morbidity and mortality associated with endovascular treatment of intracranial aneurysms. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005; 26:506–514. PMID: 15760857.

13. Ogilvy CS, Natarajan SK, Jahshan S, Karmon Y, Yang X, Snyder KV, et al. Stent-assisted coiling of paraclinoid aneurysms: risks and effectiveness. J Neurointerv Surg. 2011; 3:14–20. PMID: 21990780.

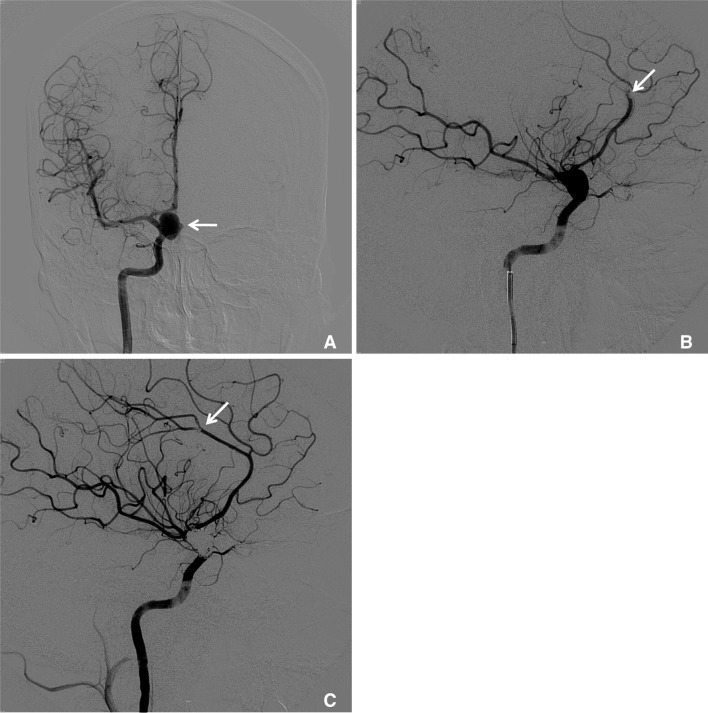

Fig. 1

A 49-year-old female with a ruptured paraclinoid aneurysm.

A. The right internal carotid angiogram reveals a 8 mm-sized aneurysm with a wide neck (arrow) arising from the paraclinoid region. B. During embolization, the angiogram showed a thrombus (arrow) at the distal ACA and no contrast staining at its territories. C. After intra-arterial thrombolysis, the angiogram showed improvement in blood flow (arrow).

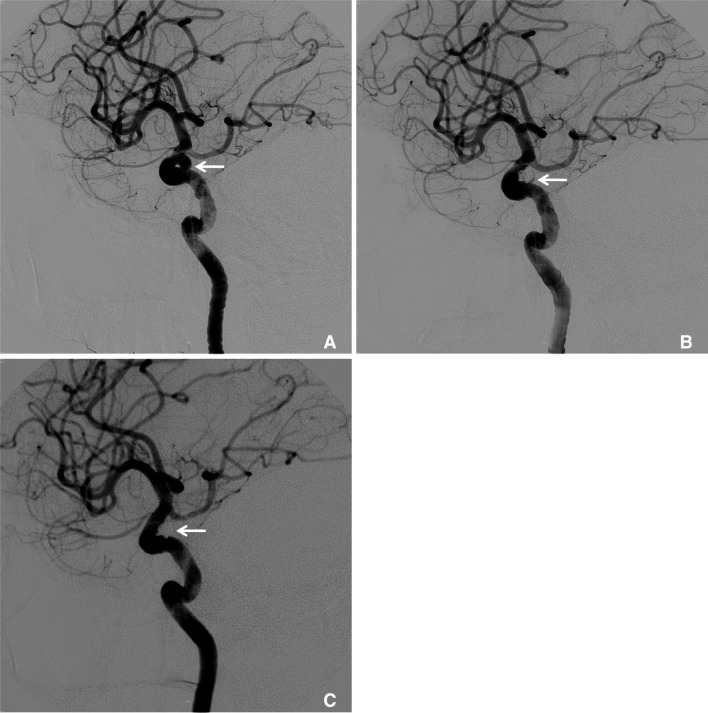

Fig. 2

A 47-year-old female with an unruptured paraclinoid aneurysm.

A. The right internal carotid angiogram reveals a 4.1 mm-sized aneurysm with a wide neck (arrow) arising from the paraclinoid region. B. An immediate angiogram after stent-assisted coil embolization showed incomplete embolization with a remnant sac (arrow). C. A right carotid angiogram obtained 8 months after coiling showed complete obliteration of the remnant sac (arrow).

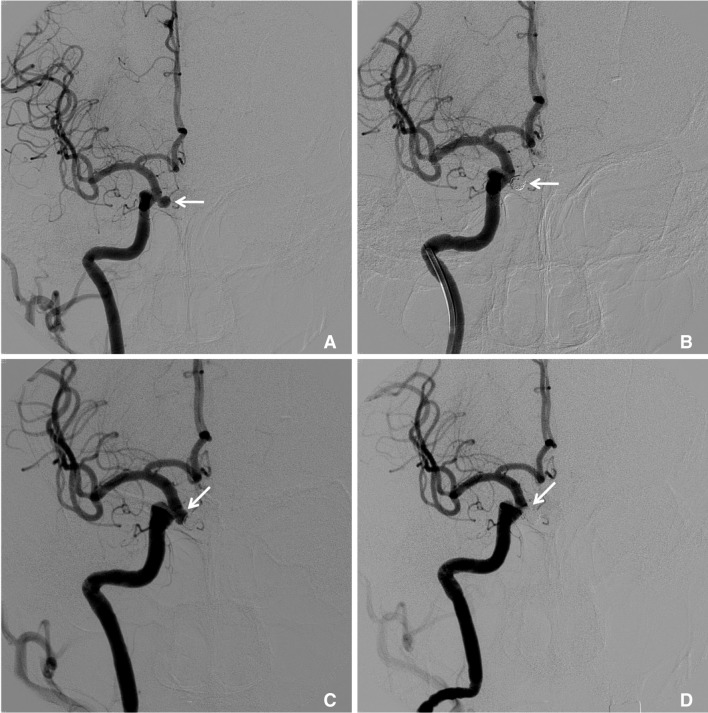

Fig. 3

A 67-year-old female with an unruptured paraclinoid aneurysm.

A. The right internal carotid angiogram reveals a 5mm-sized aneurysm (arrow) arising from the paraclinoid region. B. An immediate angiogram after simple coil embolization showed a remnant neck (arrow). C. During the follow-up, there was a newly detected recurrence of an aneurysm (arrow) about 12 years after coiling. D. A right internal carotid angiogram showed complete obliteration of the recurrent aneurysm (arrow) using a stent-assisted coil technique.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download