Abstract

Purpose

Day-care management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms can shorten hospital stay, reduce medical cost and improve outcome. We present the process, outcome and duration of hospital stay for the management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms via a neurointervention clinic in a single center during the past four years.

Materials and Methods

We analyzed 403 patients who were referred to Neurointervention Clinic at Asan Medical Center for aneurysm evaluation between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2014. There were 141 (41%) diagnostic catheter angiographies, 202 (59%) neurointerventional procedures and 2 (0.6%) neurointerventional procedures followed by operation. We analyzed the process, outcome of angiography or neurointervention, and duration of hospital stay.

Results

There was no aneurysm in 58 patients who were reported as having an aneurysm in MRA or CTA (14 %). Among 345 patients with aneurysm, there were 283 patients with a single aneurysm (82%) and 62 patients with multiple aneurysms (n=62, 18%). Aneurysm coiling was performed in 202 patients (59%), surgical clipping in 14 patients (4%), coiling followed by clipping in 2 patients (0.6%) and no intervention was required in 127 patients (37%). The hospital stay for diagnostic angiography was less than 6 hours and the mean duration of hospital stay was 2.1 days for neurointervention. There were 4 procedure-related adverse events (2%) including 3 minor and 1 major ischemic strokes.

The prevalence of aneurysms is estimated to be 2.3% (1.7, 3.1) in adults without specific risk factors for subarachnoid hemorrhage (based on the current available data) [12]. The overall rupture rate of cerebral aneurysms varies from 0.5% to 1.3% per year [1234]. Many studies showed that the natural course of unruptured intracranial aneurysms (UIAs) varies according to the location, size and shape of the aneurysm. Risk factors such as clinical symptoms, hypertension, multiplicity and family history of cerebrovascular disease should be considered in the management of patients with UIAs [1356].

With the development of non-invasive imaging technology such as MRA and CTA and increased concerns on the health-care of population aging, the incidence of detecting UIAs is expected to increase [178]. The awareness of having an UIA often exerts a significant psychological burden because of the fear of aneurysmal rupture, which may impaire the quality of life (QOL) in addition to the theoretical risks [9101112]. Endovascular coiling of UIAs was associated with apparently decreased morbidity and similar or lower mortality compared with surgical clipping [131415].

Our previous study showed that same-day care management of outpatients who underwent neuroangiography and neurointervention for various neurovascular diseases provided a shorter admission process and duration on an outpatient basis [16]. In this report, we present the process, outcome and duration of hospital stay for the management of UIAs via the Neurointervention Clinic over the past four years.

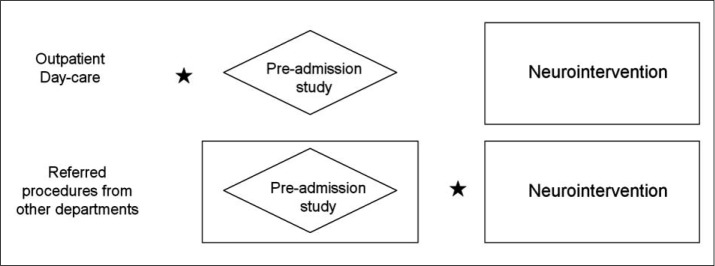

The local institutional review board approved this retrospective study, and patients provided a written informed consent for the procedure. We def ined outpatient day-care management as a clinical process where the patients get a procedure on the day of admission and are subsequently get discharged on the same day for the diagnosis or on the following day for the neurointervention, which is generally performed under general anesthesia (Fig. 1). We analyzed 412 UIAs in 345 patients who were referred to the Neurointervention Clinic of the Asan Medical Center due to known cerebral aneurysms and underwent cerebral angiography or neurointervention during the recent four years between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2014. We excluded the patients who have aneurysms associated with other cerebrovascular diseases or patients with aneurysms in the head and neck or spine. We also assessed the results of cerebral angiography including serious complications which required additional management or emergency surgery and the process of the patients, and outcome.

After the decision was made for patients with UIAs to undergo a cerebral angiography in the outpatient clinic, they underwent pre-admission study (chest PA, Electrocardiography (ECG), blood test, urine analysis) and attended the neuroangio-suite in the morning of the reserved day. Oral intake (breakfast) was prohibited for about two hours before the procedure. After a short period of post-procedural observation (4 to 6h), the majority of patients who have been performed uncomplicated cerebral angiography were discharged on the same day.

The angiography was performed via a transfemoral or transradial approach by an insertion of a 4F sheath. Both the internal carotid arteriograms and the dominant or ipsilateral (lesion side) vertebral arteriogram were performed using a 4F angiocatheter. These angiographic procedures were identifical to what would have been done as an inpatient procedure. After the procedure, manual compression of the puncture site was applied using Apad hemostasis device (T & L, Seoul, Korea) which was designed to promote bleeding control.

The preparation before the procedure was the same as that for cerebral angiography except that general anesthesia was used. A 6-7F guiding catheter was introduced into the cervical distal of targeted internal carotid artery or vertebral artery. A microcatheter was navigated in roadmap through the guiding catheter into the targeted artery. Neuroform stent (Boston Scientific Corp, Fremont, CA) or Enterprise stent (Codman Neurovascular, Miami, FL) was used in patients who were performed stent-assisted coiling. The patients received clopidogrel 75 mg daily at least 4 days before the procedure and continued for 3-6 months, and aspirin 100 mg daily for a year. All endovascular procedures were performed with patients under systemic heparinization with a range of 200-250 seconds of activated clotting time. During the procedure, the patient's vital signs were monitored by the arterial line via the radial artery. After the procedure, each patient was sent to the intensive care unit (ICU). From the ICU all patients were discharged or transferred to another department if further management or procedure was required.

We assessed the patient after angiography on whether there was any aneurysm corresponding to MRA or CTA. Treatment options were discussed with the patients and their family with an explanation of the natural risk of the aneurysm. Post-procedural events were recorded as having minor or major strokes. Minor stroke was defined as a new, nondisabling neurologic deficit or as an increase in the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) by 3 (points), but which completely resolved within 30 days [1718].

There were 403 aneurysms in 345 patients who underwent cerebral angiography and neurointervention at our institution between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2014. Male to female ratio was 3:7. Patient age ranged from 26 to 81 (mean 56). There were 141 (41%) diagnostic catheter angiographies, 202 neurointerventional procedures (59%) and 2 (0.6%) neurointerventional procedures followed by operation. Angiographic results showed a single aneurysm (n=283, 82%) or multiple aneurysms (n=62, 18%). No aneurysm was found in 58 patients who were reported as having an aneurysm in MRA or CTA. Among 345 patients with aneurysms, coiling was performed in 202 patients (59%), surgical clipping in 14 (4%), coiling followed by clipping in 2 (0.6%) and cerebral angiography follow up in 127 (37%).

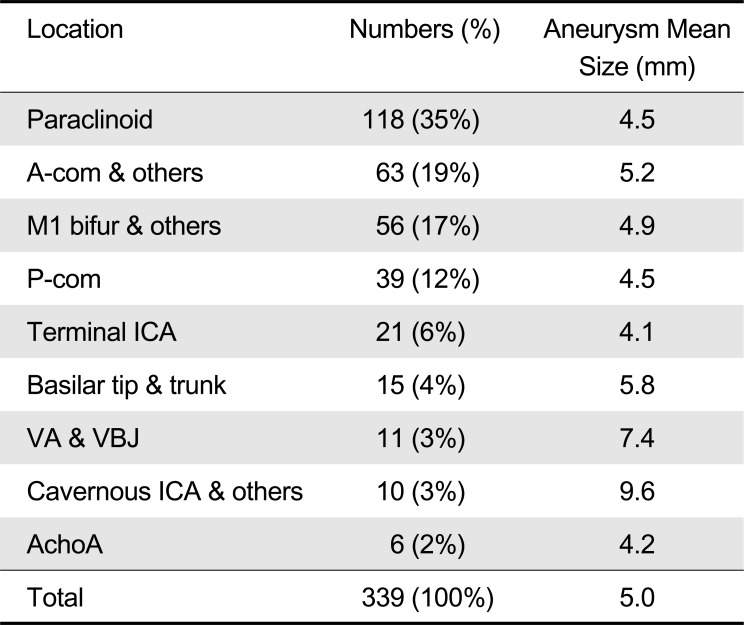

Of these aneurysms, the maximum diameter of 154 aneurysms was ≤ 4 mm, 166 aneurysms had diameters of 4-10 mm, 19 aneurysms had diameters greater than 10 mm (Table 1). There were 3 giant thrombosed or fusiform aneurysms, 2 recurred aneurysms and 1 dissecting aneurysm whose sizes were not measurable. The mean hospital stay for neurointervention was 2.1 days. In the follow-up, there were recurrent aneurysms in 9 patients who underwent 2 procedures without further event. There were no serious complications after angiography which required additional management or emergency surgery. After neurointerventional procedures, there were 4 (2%) adverse events including 3 minor and 1 major ischemic strokes.

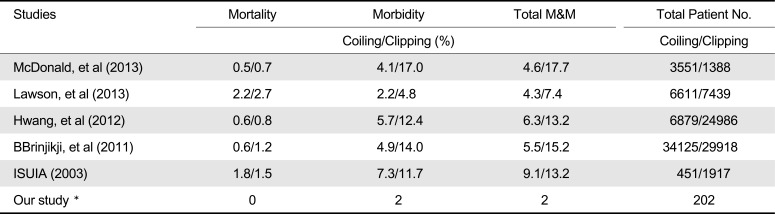

Our study revealed that day-care management of UIAs resulted in 2% adverse events and 4.5% recurrence that required additional coil embolization without further event. Outcome of outpatient neurointervention of UIAs in this study was comparable to other studies regarding endovascular treatment for inpatients with UIAs [15192021] (Table 2). The mean duration of hospital stay for neurointervention procedures for patients with UIAs was 2.1 days which were much shorter than those in a study performed by the National Evidence-based Healthcare Collaborating Agency (22 days for surgical clipping and 12 days for neurointerventional coiling) [16]. In one study of patient with ruptured and unruptured aneurysms, neurointerventional coiling, compared with surgical clipping, was associated a shorter length of hospitalization, but higher hospital cost [22]. In another study, coiling compared to clipping was associated with a signif icantly shorter hospital stay and lower total hospital charges [23]. In addition to reducing the hospitalization period and total hospital charges by using a neurointerventional procedure compared to surgery, our study demonstrated the possibility that day-care neurointerventional coiling can be used to treat UIAs.

The advantage of day-care procedures was rapid admission process on an outpatient basis. The simplification of the admission process can be achieved by close communication in the outpatient clinics by admitting to an intermediary care unit in the angiosuite. In addition, the diagnosis of an aneurysm was promptly made after a neuroangiography. After 6 hours of admission, patients who underwent uncomplicated cerebral angiography was be discharged on the same day [16]. Aneurysms considered as having relatively higher risks for rupture were scheduled after discussion with patients and their family for subsequent management.

Although in our study there were no reported significant adverse events after cerebral angiography and 4 strokes (2%) after neurointerventional procedures, there was a higher complication rate as 25% in which some patients require further treatment [24]. Therefore, improvement of procedural outcome as well as management process might affect difference in adverse events even though study population was different among the studies.

There were some limitations to our study. Firstly, we did not perform a comparative study with surgical clipping for the same category of the patients even though outcome of endovascular therapy was known to be better. Secondly, cost evaluation or comparison with surgical clipping was not performed. Reimbursement by insurance for surgery is higher than that of endovascular treatment in Korea. Further study is required for exact comparisons.

Our study reported our experience of day-care management of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. It could provide rapid patient flow in the hospital, shorten hospital stay and obtain better outcome, and is expected to reduce hospital costs Furthermore, the availability of such outpatient management can contribute to meet higher standard of medical need of a large volume of patients with UIAs.

References

1. Rinkel GJ. Natural history, epidemiology and screening of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neuroradiol. 2008; 35:99–103. PMID: 18242707.

2. Rinkel GJ, Djibuti M, Algra A, van Gijn J. Prevalence and risk of rupture of intracranial aneurysms: a systematic review. Stroke. 1998; 29:251–256. PMID: 9445359.

3. UCAS Japan Investigators. Morita A, Kirino T, Hashi K, Aoki N, Fukuhara S, et al. The natural course of unruptured cerebral aneurysms in a Japanese cohort. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:2474–2482. PMID: 22738097.

4. Juvela S, Porras M, Poussa K. Natural history of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: probability of and risk factors for aneurysm rupture. J Neurosurg. 2008; 108:1052–1060. PMID: 18447733.

5. You SH, Kong DS, Kim JS, Jeon P, Kim KH, Roh HK, et al. Characteristic features of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: predictive risk factors for aneurysm rupture. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010; 81:479–484. PMID: 19726404.

6. Jeon JS, Ahn JH, Huh W, Son YJ, Bang JS, Kang HS, et al. A retrospective analysis on the natural history of incidental small paraclinoid unruptured aneurysm. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014; 85:289–294. PMID: 23781005.

7. Nagamine Y. Natural history and management of asymptomatic unruptured cerebral aneurysms. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2004; 44:763–766. PMID: 15651285.

8. Unruptured intracranial aneurysms--risk of rupture and risks of surgical intervention. International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998; 339:1725–1173. PMID: 9867550.

9. Yoshimoto Y, Tanaka Y. Risk perception of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2013; 155:2029–2203. PMID: 23921577.

10. Buijs JE, Greebe P, Rinkel GJ. Quality of life, anxiety, and depression in patients with an unruptured intracranial aneurysm with or without aneurysm occlusion. Neurosurgery. 2012; 70:868–872. PMID: 21937934.

11. King JT Jr, Tsevat J, Roberts MS. Preference-based quality of life in patients with cerebral aneurysms. Stroke. 2005; 36:303–330. PMID: 15653579.

12. Yamashiro S, Nishi T, Koga K, Goto T, Kaji M, Muta D, et al. Improvement of quality of life in patients surgically treated for asymptomatic unruptured intracranial aneurysms. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007; 78:497–500. PMID: 17178825.

13. McDonald JS, McDonald RJ, Fan J, Kallmes DF, Lanzino G, Cloft HJ. Comparative effectiveness of unruptured cerebral aneurysm therapies: propensity score analysis of clipping versus coiling. Stroke. 2013; 44:988–994. PMID: 23449260.

14. Hwang JS, Hyun MK, Lee HJ, Choi JE, Kim JH, Lee NR, et al. Endovascular coiling versus neurosurgical clipping in patients with unruptured intracranial aneurysm: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2012; 12:99. PMID: 22998483.

15. Brinjikji W, Rabinstein AA, Nasr DM, Lanzino G, Kallmes DF, Cloft HJ. Better outcomes with treatment by coiling relative to clipping of unruptured intracranial aneurysms in the United States, 2001-2008. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2011; 32:1071–1075. PMID: 21511860.

16. Jeong YG, Kim EH, Hwang SM, Lee GY, Kim JW, Choi YJ, et al. Outpatient (Same-day care) Neuroangiography and Neurointervention. Neurointervention. 2012; 7:17–22. PMID: 22454780.

17. Lu PH, Park JW, Park S, Kim JL, Lee DH, Kwon SU, et al. Intracranial stenting of subacute symptomatic atherosclerotic occlusion versus stenosis. Stroke. 2011; 42:3470–3476. PMID: 21940974.

18. Suh DC, Kim JK, Choi JW, Choi BS, Pyun HW, Choi YJ, et al. Intracranial stenting of severe symptomatic intracranial stenosis: results of 100 consecutive patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2008; 29:781–785. PMID: 18310234.

19. Kwon SC, Kwon OK. Korean Unruptured Cerebral Aneurysm Coiling Investigators. Endovascular coil embolization of unruptured intracranial aneurysms: a Korean multicenter study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2014; 156:847–885. PMID: 24610449.

20. Naggara ON, Lecler A, Oppenheim C, Meder JF, Raymond J. Endovascular treatment of intracranial unruptured aneurysms: a systematic review of the literature on safety with emphasis on subgroup analyses. Radiology. 2012; 263:828–835. PMID: 22623696.

21. Yue W. Endovascular treatment of unruptured intracranial aneurysms. Interv Neuroradiol. 2011; 17:420–424. PMID: 22192544.

22. Hoh BL, Chi YY, Dermott MA, Lipori PJ, Lewis SB. The effect of coiling versus clipping of ruptured and unruptured cerebral aneurysms on length of stay, hospital cost, hospital reimbursement, and surgeon reimbursement at the university of Florida. Neurosurgery. 2009; 64:614–619. PMID: 19197221.

23. Hoh BL, Chi YY, Lawson MF, Mocco J, Barker FG 2nd. Length of stay and total hospital charges of clipping versus coiling for ruptured and unruptured adult cerebral aneurysms in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database 2002 to 2006. Stroke. 2010; 41:337–342. PMID: 20044522.

24. Gradinscak DJ, Young N, Jones Y, O'Neil D, Sindhusake D. Risks of outpatient angiography and interventional procedures: a prospective study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004; 183:377–381. PMID: 15269028.

Fig. 1

Process diagram of patient flow. Comparison between outpatient daycare and referred procedures. Preadmission study = chest PA, Electrocardiography (ECG), blood test and urine analysis; ★ = consultation for neurointervention; ◇ = Pre-admission study; ⬜ = Admission status

Table 1

Location and Proportion of 345 Patients with Aneurysms

Sizes of six aneurysms (3 giant thrombosed or fusiform, 2 recurred and 1 dissecting) were not measurable. A-com = the anterior communicating artery, bifur = bifurcation, ICA = the internal carotid artery, VA = the vertebral artery, VBJ = the vertebra-basilar junction, AchA = the anterior choroidal artery

Table 2

Morbidity and Mortality between Surgical Clipping and Endovascular Coiling of UIAs in Different Studies

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download