Abstract

Objective

To investigate the current status of pharmacotherapy prescribed by physiatrists in Korea for cognitive-behavioral disorder.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was performed by mailing questionnaires to 289 physiatrists working at teaching hospitals. Items on the questionnaire evaluated prescribing patterns of 16 drugs related to cognitive-behavioral therapy, the status of combination pharmacotherapy, and tools for assessing target symptoms.

Results

Fifty physiatrists (17.3%) including 24 (48%) specializing in neurorehabilitation completed the questionnaires. The most common target symptom was attention deficit (29.5%). Donepezil and methylphenidate (96.0%) were the most frequently prescribed drugs for cognitive-behavioral improvement. Mostly, a combination of two drugs was prescribed (38.0%), and the most common combination therapy included donepezil plus methylphenidate (19.1%). Pharmacotherapy for cognitive-behavioral disorder after brain injury was typically initiated within 2 months (69.5%). A follow-up assessment was usually performed at 1 month after treatment initiation (31.0%). The most common reason for treatment discontinuation was improvement of target symptoms (37.8%). The duration of pharmacotherapy was 3–12 months (57.7%), 1–2 years (17.9%), or 1–2 months (13.6%).

Conclusion

According to the survey, combination pharmacotherapy is preferred to monotherapy for the treatment of cognitive-behavioral disorder in patients with brain injury. Physiatrists expressed diverse views on the definition of target symptoms, prescribing patterns, and the status of drug combination therapy. Guidelines are needed for cognitive-behavioral pharmacotherapy. Further research should investigate drug costs and aim to reduce polypharmacy and adverse drug reactions.

Go to :

Stroke or traumatic brain injury is one of the leading causes of death in Korea, and those who survive are often left with severe neurological disorders [1]. Physiatrists have focused specifically on cognitive-behavioral symptoms especially those resulting from brain injury including agitation, anger, anxiety, depression, inattention, hypoarousal, irritability, insomnia, abulia, emotional lability, memory deficit, and obsessive-compulsive disorder [2]. Both non-pharmacological and pharmacological strategies are available to manage these symptoms in patients with brain injury. Non-pharmacological therapies include behavioral therapy, complementary therapy, aromatherapy, and bright-light therapy, as well as cognitive-behavioral therapies [3]. Pharmacological therapies are aimed at facilitating motor recovery and improving a patient's level of consciousness and cognitive or behavioral symptoms [4]. The use of pharmacotherapy in the management of cognitive-behavioral disorder in patients with stroke or traumatic brain injury has been increasingly adopted in neurorehabilitation medicine.

Previous studies have reported that multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy were more common in patients who have had stroke compared with those who have not [5]. These studies underscore the importance of adopting standard guidelines for pharmacotherapy in managing cognitive-behavioral disorders [5]. It is essential to consider the side effects and drug-interactions when prescribing additional medications for cognitive-behavioral improvements in the elderly or in patients who have had a stroke given underlying diseases and pre-existing polypharmacy.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has investigated the frequency of medications that are prescribed or the outcomes of polypharmacy for cognitive-behavioral disorder after brain injury [1]. The aim of our study was to survey the current status of pharmacotherapy prescribed by physiatrists in Korea for cognitive-behavioral improvement using a questionnaire. In particular, we investigated the lack of guidelines for pharmacotherapy despite the use of multiple medications for patients with brain injury in Korea.

Go to :

This cross-sectional study was conducted via mailed questionnaires. The questionnaires were sent to 289 physiatrists across all subspecialties working in 82 hospitals. The hospitals included private rehabilitation clinics, physical medicine and rehabilitation (PM&R) departments in general hospitals, specialized rehabilitation hospitals, and university-affiliated rehabilitation centers in Korea.

The survey questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section contained questions involving the participant's affiliation, position, subspecialty, and preference for prescribing cognitive-behavioral drugs for the target symptoms. In the second section, physiatrists responded to questions aimed at investigating their prescribing patterns of 16 medications, including amantadine, atomoxetine, bromocriptine, carbamazepine, donepezil, haloperidol, levodopa, memantadine, methylphenidate, modafinil, quetiapine, risperidone, rivastigmine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), and valproic acid [2].

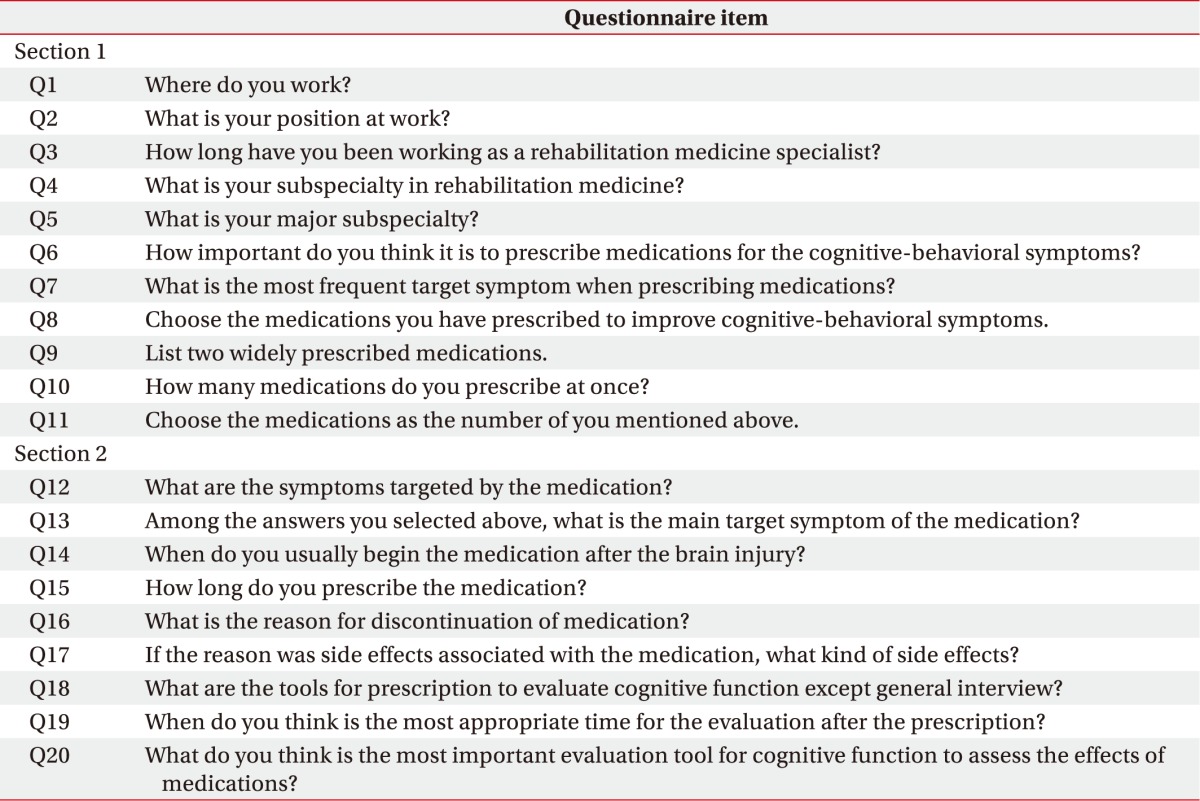

Respondents answered 9 questions related to each of the 16 medications including target symptoms, medication start time after brain injury, status of combination therapy, duration of therapy, reasons for discontinuation of medication, side effects, and assessment tools for target symptoms. Target symptoms included agitation, arousal disorder, attention deficit, depression, emotional lability, executive function deficit, memory deficit, mood disorder, poor motivation, neurogenic fatigue, and speech or language disorder. Sleep disorder and epilepsy were excluded from the study. Responders were allowed to select multiple answer choices on the questionnaire (Table 1).

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the responders and categorize the answers.

Go to :

Of the 289 physiatrists receiving the questionnaires by mail, 50 completed and returned the surveys, yielding a response rate of 17.3%. Responders worked at 36 of the original 82 hospitals contacted, yielding a hospital response rate of 43.9%.

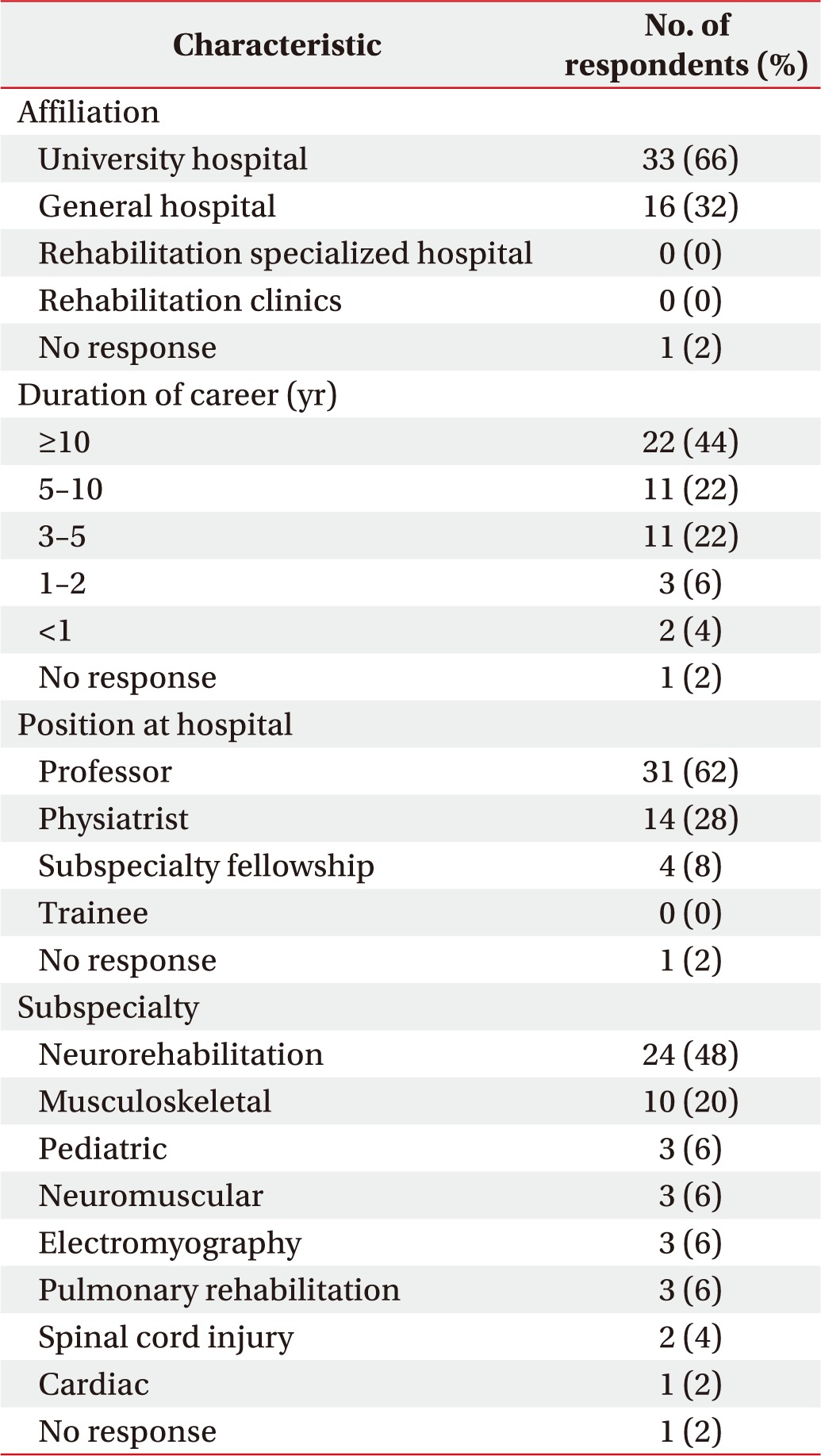

Most of the participants (66%) were working at university hospitals, and 32% worked at general hospitals. Twenty-two respondents (44%) had worked for more than 10 years as a physiatrist, 11 (22%) had worked for 5 to 10 years, and 11 (22%) had worked for 3 to 5 years. A total of 31 respondents (62%) were professors at university hospitals and 14 (28%) were physiatrists. Twenty-four respondents (48%) sub-specialized in neurorehabilitation, 10 (20%) in musculoskeletal rehabilitation, and 3 (6%) in pediatric rehabilitation (Table 2).

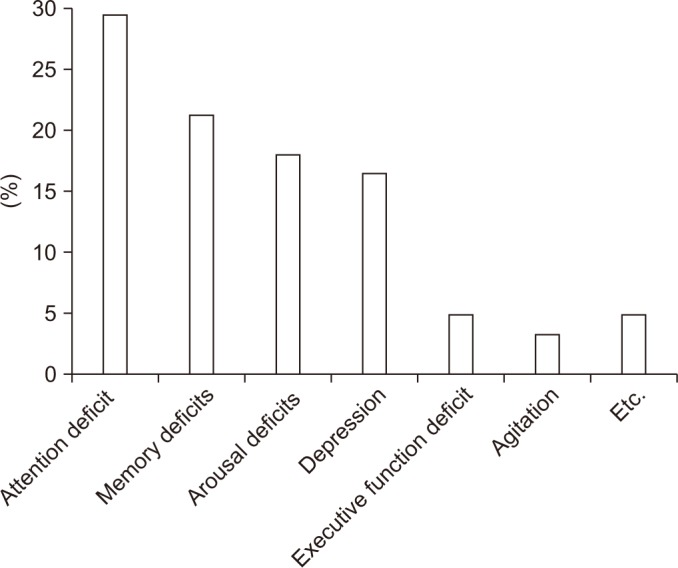

Attention deficit was the cognitive-behavioral symptom that was most commonly targeted by physiatrists (29.5%), followed by memory deficit (21.3%), arousal deficit (18%), depression (16.4%), executive function deficit (4.9%), agitation (3.3%), emotional lability (1.6%), poor motivation (1.6%), and speech and language disorder (1.6%) (Fig. 1).

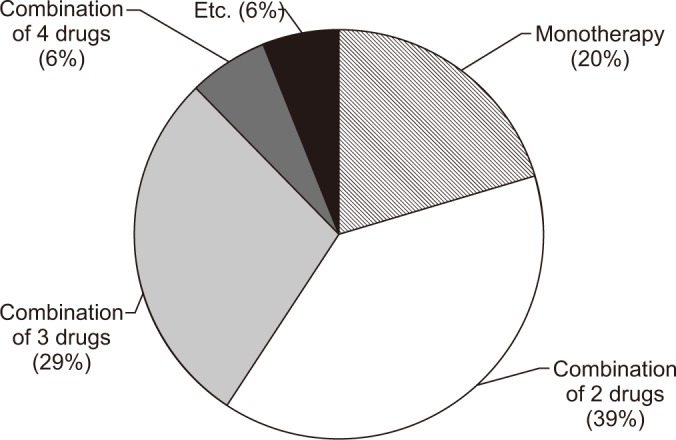

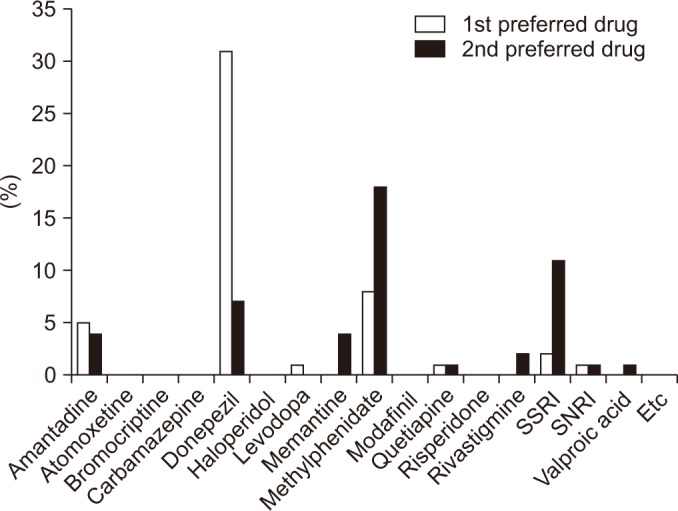

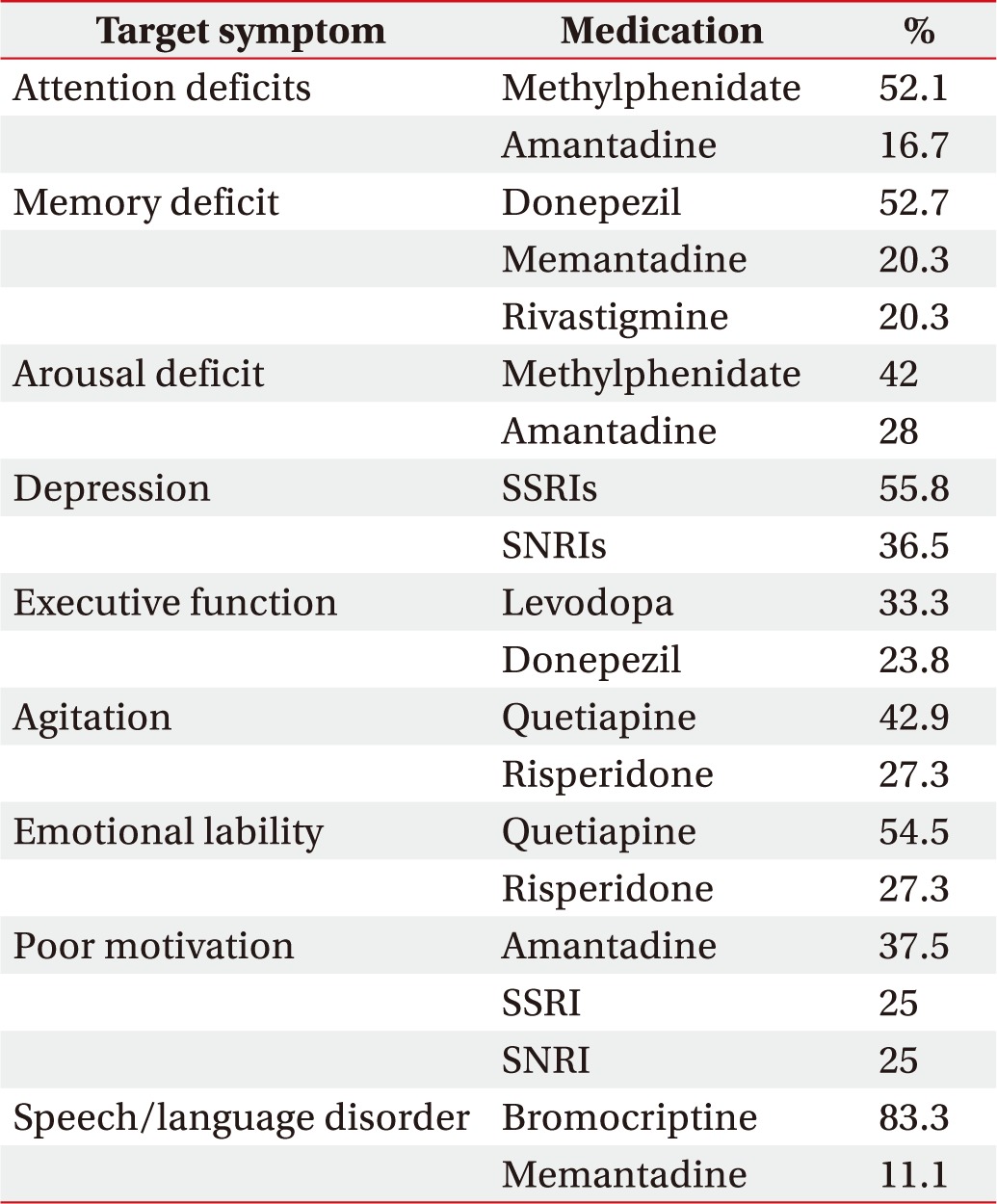

Methylphenidate (52.1%) and amantadine (16.7%) were the most frequently prescribed medications for attention deficit. Donepezil (52.7%), memantadine (20.3%) and rivastigmine (20.3%) were the most frequently prescribed medications for memory deficit. Methylphenidate (42%) and amantadine (28%) were the most frequently prescribed medications for arousal deficit. SSRIs (55.8%) and SNRIs (36.5%) were the most frequently prescribed medications for depression. Table 3 shows the most commonly prescribed medications for treatment of each of the target symptoms associated with cognitive-behavioral disorder. Physiatrists generally prescribed a combination of two cognitive-behavioral medications (39%), followed by a combination of three medications (29%), monotherapy (20%) and a combination of four medications (6%) (Fig. 2). Donepezil and methylphenidate (96%) were the most preferred medications for cognitive-behavioral improvement, followed by SSRIs (84%), quetiapine (84%), bromocriptine (72%), and amantadine (68%). Among the several medications, respondents preferred donepezil as a first line drug and methylphenidate as a second line drug (19.1%) in combination pharmacotherapy (Fig. 3).

Pharmacotherapy was mostly initiated 1 to 2 months (39.3%) after the brain injury, followed by <1 month (30.2%), 3 to 6 months (18.2%) and over 6 months (8.8%). Pharmacotherapy was most commonly started within 2 months of the stroke or traumatic brain injury (69.5%). The duration of pharmacotherapy for cognitive-behavioral disorders was 6 to 12 months (30.1%), followed by 3 to 6 months (27.5%), 1 to 2 years (17.9%), 1 to 2 months (13.6%) and <1 month (6.8%). Pharmacotherapy was maintained for 3 to 12 months by 57.6% of respondents.

Medications were discontinued mostly due to symptom improvement and satisfactory outcomes (37.8%), followed by absence of effect (36.3%), adverse drug reactions (22.9%), and non-compliance by patient or caregiver (2.4%). The most common time point for assessing the effect of treatment was one month after the initiation of pharmacotherapy (30.9%). In 14.9% of cases, assessment was performed after 6 months of treatment initiation and in 15.7% of cases, no follow-up occurred.

No statistical significance was found in the number of prescribed medications among subgroups of respondents regarding participant characteristics. The subgroups were affiliation (p=0.503), position at hospital (p=0.897), duration of career (p=0.135) and subspecialty (p=0.410).

Among the medications listed on the survey questionnaire, seven drugs prescribed at least once by physiatrists were amantadine, donepezil, levodopa, methylphenidate, quetiapine, SSRI and SNRI. Consequently, no statistical significance was seen in the preference for first-line drug prescription among subgroups, affiliation (p=0.660), position at hospital (p=0.252), duration of career (p=0.182) or subspecialty (p=0.418).

Go to :

Although medications for cognitive-behavioral disorder have been widely prescribed to patients with stroke or traumatic brain injury, to the best of our knowledge, no previous studies have investigated the prescribing preferences of physiatrists in Korea. The aim of this study was to investigate the current status of pharmacotherapy in Korea for cognitive-behavioral improvement. The survey responses provided meaningful information regarding the type of cognitive-behavioral medications that Korean physiatrists prescribe for patients with brain injury, as well as the time at which they are prescribed, the duration of treatment, and whether or not they are recommended as part of a combination therapy. The results revealed that the most concerning target symptoms were attention deficit, memory deficit, hypoarousal, and depression. The preferred prescription drugs included methylphenidate and amantadine for attention deficit; donepezil, memantadine, and rivastigmine for memory deficit; methylphenidate and amantadine for hypoarousal; and SSRIs and SNRIs for depression.

Pharmacological intervention for cognitive-behavioral symptoms after a stroke is only recommended in limited cases and is based on clinical considerations [1]. There are no standard guidelines for cognitive-behavioral medication after brain injury, although previous studies have shown that pharmacotherapy was useful in brain injury. Memantadine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist has been approved as an effective treatment for improving cognitive function in patients with moderate to severe cognitive impairment of vascular origin [6]. In these patients, acetylcholine esterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine, are also approved for improving cognitive function [6]. According to another study, donepezil is also indicated as an effective treatment for memory deficit in patients sustaining a brain injury [7].

In a study by Sivan et al. [8], methylphenidate was shown to improve information processing speed, without covering all the aspects of attention. Whyte et al. [9] reported that methylphenidate treatment for traumatic brain injury significantly improves speed of processing, caregiver ratings of attention, and a few aspects of on-task behavior in naturalistic tasks. While methylphenidate appears to improve attention deficits, little is known about the role of amantadine in attention deficit disorder. During active treatment, amantadine accelerated the pace of functional recovery in patients with post-traumatic disorder of consciousness [10]. Although the results of our survey suggest that amantadine may be beneficial in treating attention deficits, further studies are required to determine the best medications for the treatment of target symptoms.

A majority of the respondents preferred to prescribe a combination of two cognitive-behavioral medications rather than a combination of three or a monotherapy. Among the several drugs prescribed in combination, responders preferred donepezil as a first-line drug and methylphenidate as a second-line drug. The term polypharmacy has been defined in several different ways, but the most common definition includes the simultaneous use of multiple medications [11]. Therefore, polypharmacy can be considered as a direct measure of one aspect of the treatment burden [5]. A recent focus related to negative consequences that have been associated with polypharmacy. Collet et al. [12] reported that an increase in the number of central nervous system (CNS)-acting medications was strongly associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and traumatic brain injury, and that CNS polypharmacy may be an indicator of risk for adverse outcomes. Furthermore, an increase in health costs, adverse drug events, unintentional drug interactions, and falls, as well as negative influences on nutritional status are several limitations of polypharmacy [13]. Among these challenges, unintentional drug interactions are unpredictable and can lead to detrimental complications. Negative drug interactions may alter cardiac, gastrointestinal, neuropsychological, and urinary functions. As it is nearly impossible to predict these negative drug interactions, it is necessary to clarify and define the target symptoms and determine the minimum number of pharmacotherapies required for treatment.

This study has several limitations. First, the survey responses may not be representative of all Korean physiatrists due to an insufficient response rate. To increase reliability, a higher response rate and a larger study group are necessary. Furthermore, the survey respondents included all physiatrists, rather than the more specialized subgroup of neurorehabilitation specialists. Thus, the survey responses may not specifically represent the prescription patterns of Korean physiatrists specialized in neurorehabilitation. Second, the etiology, pathophysiology, symptoms, treatment, and prognosis of stroke and traumatic brain injury are different, and the questionnaire did not categorize responses according to disease type. Third, the medications listed on the survey questionnaire were not clearly classified. It would have been better if the drugs were either categorized according to reaction mechanisms or listed separately instead of alphabetical order. Further, we should have included other drugs such as benzodiazepines and tricyclic antidepressants. Fourth, depression, emotional lability and neurogenic fatigue should have been included in the category of mood disorder to avoid uncertainty. It would have been better if the definitions were indicated on the survey questionnaire. Fifth, the survey failed to include new-generation drugs that are used to treat the target symptoms. For example, zolpidem has emerged as an effective treatment for improving consciousness levels in traumatic brain injury [4]. Moreover, the survey questionnaire did not include items aimed at addressing the influence of health insurance systems. Prescription of certain medications for cognitive-behavioral symptoms in brain injury is strictly limited, as the Korean medical system operates under a national health insurance service. Lastly, the article pertains to the prescription trends of pharmacotherapy for cognitive-behavioral disorder in brain-injured patients. We wondered whether there were differences in terms of prescription trends among subgroups of respondents. Differences between two groups were evaluated using Fisher exact test. As a result, there were no significant differences in the number of drugs. In addition, no significant differences in preferred prescription patterns among subgroups were noted. Further study with a large sample size is necessary to analyze the significance of prescription trends among the subgroups.

Although physiatrists apply several medications to manage cognitive-behavioral symptoms in patients sustaining a stroke or traumatic brain injury, strong evidence for the use of pharmacotherapy for each of the aforementioned target symptoms is still lacking. Many physiatrists are interested in understanding the optimal timing, type, and duration of pharmacotherapy, as well as the negative effects of polypharmacy. Although this cross-sectional study may not be truly representative of all Korean physiatrists, this initial survey provides meaningful insight into the current status of pharmacotherapy for cognitivebehavioral disorder in patients with brain injury. Further research is necessary to strengthen the evidence for the use of pharmacotherapy in brain injury.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a 2-year Research Grant of Pusan National University.

Go to :

References

1. Rah UW, Kim YH, Ohn SH, Chun MH, Kim MW, Yoo WK, et al. Clinical practice guideline for stroke rehabilitation in Korea 2012. Brain Neurorehabil. 2014; 7(Suppl 1):S1–S75.

2. Francisco GE, Walker WC, Zasler ND, Bouffard MH. Pharmacological management of neurobehavioural sequelae of traumatic brain injury: a survey of current physiatric practice. Brain Inj. 2007; 21:1007–1014. PMID: 17891562.

3. Sadowsky CH, Galvin JE. Guidelines for the management of cognitive and behavioral problems in dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012; 25:350–366. PMID: 22570399.

4. Liepert J. Update on pharmacotherapy for stroke and traumatic brain injury recovery during rehabilitation. Curr Opin Neurol. 2016; 29:700–705. PMID: 27748687.

5. Gallacher KI, Batty GD, McLean G, Mercer SW, Guthrie B, May CR, et al. Stroke, multimorbidity and polypharmacy in a nationally representative sample of 1,424,378 patients in Scotland: implications for treatment burden. BMC Med. 2014; 12:151. PMID: 25280748.

6. Kavirajan H, Schneider LS. Efficacy and adverse effects of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine in vascular dementia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Lancet Neurol. 2007; 6:782–792. PMID: 17689146.

7. Taverni JP, Seliger G, Lichtman SW. Donepezil medicated memory improvement in traumatic brain injury during post acute rehabilitation. Brain Inj. 1998; 12:77–80. PMID: 9483340.

8. Sivan M, Neumann V, Kent R, Stroud A, Bhakta BB. Pharmacotherapy for treatment of attention deficits after non-progressive acquired brain injury: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2010; 24:110–121. PMID: 20103574.

9. Whyte J, Hart T, Vaccaro M, Grieb-Neff P, Risser A, Polansky M, et al. Effects of methylphenidate on attention deficits after traumatic brain injury: a multi-dimensional, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2004; 83:401–420. PMID: 15166683.

10. Giacino JT, Whyte J, Bagiella E, Kalmar K, Childs N, Khademi A, et al. Placebo-controlled trial of amantadine for severe traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:819–826. PMID: 22375973.

11. Oyarzun-Gonzalez XA, Taylor KC, Myers SR, Muldoon SB, Baumgartner RN. Cognitive decline and polypharmacy in an elderly population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015; 63:397–399. PMID: 25688619.

12. Collett GA, Song K, Jaramillo CA, Potter JS, Finley EP, Pugh MJ. Prevalence of central nervous system polypharmacy and associations with overdose and suicide-related behaviors in Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans in VA care 2010–2011. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2016; 3:45–52.

13. Maher RL, Hanlon J, Hajjar ER. Clinical consequences of polypharmacy in elderly. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014; 13:57–65. PMID: 24073682.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download