Abstract

Palatal myoclonus (PM) is a rare disease that may induce dysphagia. Since dysphagia related to PM is unique and is characterized by myoclonic movements of the involved muscles, specific treatments are needed for rehabilitation. However, no study has investigated the treatment effectiveness for this condition. Therefore, the aim of this case report was to describe the benefit of combining behavioral treatment with valproic acid administration in patients with dysphagia triggered by PM. The two cases were treated with combined treatment. The outcomes evaluated by videofluoroscopic swallowing studies before and after the treatment showed significant decreases in myoclonic movements and improved swallowing function. We conclude that the combined treatment was effective against dysphagia related to PM.

Go to :

Palatal myoclonus (PM) is a rare disease triggered by myoclonic contractions of palatal musculature. PM is strongly associated with dysphagia involving the swallowing muscles such as the soft palate, pharynx, and larynx [1234]. Involuntary contractions of these muscles may cause penetration or aspiration of bolus materials [4], as suggested by previous case reports showing symptoms of swallowing difficulty in this condition [156]. Hence, the close relationship between PM and dysphagia and its unique characteristics underscore the need for specific therapeutic interventions.

In order to control dysphagia associated with PM, two types of intervention have been suggested: behavioral and medication treatment [4]. The behavioral treatment suggested supraglottic and super-supraglottic swallowing [1]. However, no study has demonstrated the effects of behavioral intervention on this condition. Similarly, no medication has been definitively established for this condition currently [4]. A single case report noted that valproic acid may have beneficial effects on PM [5], however, this report focused mainly on the respiratory challenges encountered with PM rather than dysphagia. Another case report discussed the dysphagia caused by PM in the elderly. However, this report only provided educational treatment regarding a modified diet without providing any of the aforementioned treatment interventions [7].

Accordingly, we describe two rare cases of dysphagia associated with PM, and highlight the effects of combinatorial approaches consisting of behavioral treatment and valproic acid administration.

Go to :

A 41-year-old man with a history of pontine hemorrhage that occurred on May 2014 was admitted to our rehabilitation unit 1.5 years after the event. The brain computed tomography (CT) revealed hemorrhagic lesions in the bilateral pons, and additional lesions were detected in the right than in the left side. The brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, which was conducted 6 months after the onset of hemorrhage revealed bilateral hypertrophic olivary degeneration (HOD). The cranial nerve examination revealed normal pupillary reaction, normal corneal and gag reflexes. In addition, the patient did not present any nystagmus, uvular deviation or impaired sense of taste. However, mild facial weakness and facial sensory changes were notable on his left face.

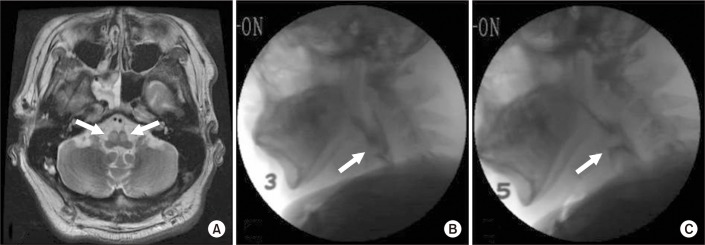

In the initial videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS), bilateral myoclonic movements of the soft palate, pharynx, and larynx were clearly observed at a frequency of 1 to 2 Hz. He revealed premature bolus loss (PBL) in the oral preparatory and oral phase, and decreased laryngeal elevation and protraction during the pharyngeal phase due to PM. He also presented with large amount (7 mL) of dysphagia diet level 3 (mildly thick, honey-like consistency), and a score of 4 on the penetration-aspiration scale (PAS) (Fig. 1). We defined the dysphagia diet level by administering the standardized dysphagia diet developed by Han et al. [8].

Following the initial VFSS, the patient was exposed to a combination of behavioral and valproic acid treatments for 2 weeks. In the behavioral treatment component, the patient performed oromotor exercises focusing on the soft palate, deliberate swallowing, and double and multiple swallowing techniques. Further, he was instructed to maintain a chin-tuck posturing while having meals. Valproic acid was administered at 450 mg/day in the first week and doses were increased up to 900 mg/day in the second week.

Two weeks of combined treatment resulted in a significant decrease in palatal myoclonic movements occurring at a frequency of a 0.5 Hz during the follow-up VFSS assessment, which occurred 14 days after the initial assessment. He showed a penetration of large amount of dysphagia diet level 5 (thin, water consistency), which corresponds to a PAS score of 4 (Fig. 1). His score on the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association National Outcome Measurement System (ASHA-NOMS) swallowing scale was also improved from 4 to 5.

The patient was a 22-year-old man with a previous history of cerebellar hemorrhage that occurred in July 2016. He was admitted to our rehabilitation unit, 3.5 months from the event. The brain CT revealed hemorrhagic lesions in the bilateral cerebellum, with intraventricular hemorrhage in the fourth ventricle. The brain MRI, which was performed 4 months after the onset of the hemorrhage, revealed bilateral HODs. The cranial nerve examination indicated normal pupillary reaction, a normal corneal reflex, and a normal gag reflex. Moreover, he showed no facial palsy symptoms, no facial weakness or sensory change, no tongue or uvular deviation, and no nystagmus.

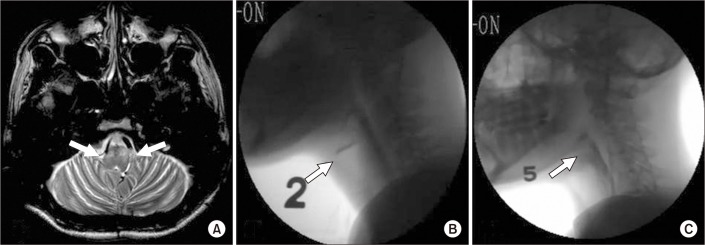

During the initial VFSS, bilateral myoclonic movements of the soft palate, pharynx, and larynx were found at a frequency of 2 to 3 Hz. The results showed a history of penetration of large amount of dysphagia diet level 3, which corresponded to a PAS score of 4, and aspiration of small amount (3 mL) of dysphagia diet level 2 (thick, pudding-like consistency) based on the standardized dysphagia diet developed by Han et al. [8], which corresponds to a PAS score of 6. Dysphagia occurred with PBL in addition to a decrease in laryngeal protection during the pharyngeal phase induced by PM (Fig. 2).

After the initial VFSS, the patient received a combination of behavioral treatment and medications for a week. In the behavioral intervention, we administered oromotor exercises focusing on the soft palate and vocal cord adduction, in addition to laryngeal elevation exercises. Moreover, the patient learned to maintain chin-tuck posturing during meals and use of multiple swallowing techniques. In the medication treatment component, valproic acid was administered at a dosage of 300 mg/day for a week.

A week of combined treatment significantly decreased the myoclonic movements, at a frequency of 1 Hz, during the follow-up VFSS assessment. Accordingly, dysphagia also improved with no penetration or aspiration of large amounts of dysphagia diet level 5 (Fig. 2). Additionally, his ASHA-NOMS score was substantially improved from 3 to 5.

Go to :

Our results provide the first evidence underscoring the clinical implications of treatment strategies for dysphagia related to PM. Both the examined cases presented with dysphagia due to PM caused by HOD. HOD is a form of trans-synaptic degeneration, most commonly triggered by focal lesions to the dentato-rubro-olivary pathway. The clinical hallmark of HOD is PM [910], which often results in dysphagia by interfering with the coordination of the muscles involved such as the soft palate, larynx, and pharynx [123].

The initial VFSS clearly showed the incidence of myoclonic movements of the soft palate, pharynx, and larynx in both cases. The first case presented with PBL and decreased laryngeal elevation and protraction during swallowing. In this case, PBL occurred due to myoclonic movements of the soft palate disrupting the contact of the soft palate with the tongue base to prevent spillages while manipulating the bolus. Moreover, decreased laryngeal elevation and protraction were attributed to myoclonic disruptions of the laryngeal muscles. Similarly, the second case presented with PBL and decreased laryngeal protection due to PM.

Behavioral treatment and medication have been suggested to control this condition in previous studies [4]. Therefore, we administered a combined treatment protocol consisting of both behavioral and medication approaches. Several medications were used (e.g., carbamazepine, phenytoin, sedatives, valproic acid, and antispasmodics) for this condition in previous studies, without definitive recommendations [4]. Based on a previous case report highlighting the beneficial role of valproic acid in respiratory problems due to PM [5], we investigated this compound in our therapeutic study. The results demonstrated the beneficial effects on dysphagia symptoms caused by myoclonic movements. The effects may result from augmenting the inhibitory influence of GABA [15]. During the behavioral treatment, in the first case, we conducted an oromotor exercise focusing on the soft palate, in an attempt to increase its voluntary movements. Effortful swallowing was also used to increase the pharyngeal wall pressure, since myoclonic movements of the soft palate and pharynx reduced this pressure. Similarly, the second case was treated with behavioral and therapeutic medications, which the first case received, in addition to vocal cord adduction and laryngeal elevation exercises to increase laryngeal elevation and airway protection based on the patient's severe myoclonic movements involving laryngeal muscles predominantly.

The combined treatment yielded positive effects in both cases. The follow-up VFSS showed a clear reduction in both amplitude and frequency of myoclonic movements, and the swallowing function improved substantially. We suggest that valproic acid is effective in reducing myoclonic movements, and behavioral treatment adequately restored the functional ability of the affected muscles in this condition.

Go to :

References

1. Drysdale AJ, Ansell J, Adeley J. Palato-pharyngo-laryngeal myoclonus: an unusual cause of dysphagia and dysarthria. J Laryngol Otol. 1993; 107:746–747. PMID: 8409734.

2. Deuschl G, Toro C, Hallett M. Symptomatic and essential palatal tremor. 2. Differences of palatal movements. Mov Disord. 1994; 9:676–678. PMID: 7845410.

3. Hanson B, Ficara A, McQuade M. Bilateral palatal myoclonus: pathophysiology and report of a case. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1985; 59:479–481. PMID: 3859808.

4. Hegland KW. Palatal myoclonus. In : Jones HN, Rosenbek JC, editors. Dysphagia in rare conditions: an encyclopedia. Hong Kong: Plural Publishing;2009. p. 449–454.

5. Sumer M. Symptomatic palatal myoclonus: an unusual cause of respiratory difficulty. Acta Neurol Belg. 2001; 101:113–115. PMID: 11486557.

6. Goossens D, Guatterie M, Barat M, de Seze M. Palatal myoclonus and dysphagia. Ann Readapt Med Phys. 2004; 47:13–19. PMID: 14967568.

7. Juby AG, Shandro P, Emery D. Palato-pharyngo-laryngeal myoclonus: an unusual cause of dysphagia. Age Ageing. 2014; 43:877–879. PMID: 24950689.

8. Han TR, Paik NJ, Park JW, Lee EK, Park MS. Standardization of dysphagia diet. Korean J Stroke. 2000; 2:191–195.

9. Krings T, Foltys H, Meister IG, Reul J. Hypertrophic olivary degeneration following pontine haemorrhage: hypertensive crisis or cavernous haemangioma bleeding? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003; 74:797–799. PMID: 12754356.

10. Salamon-Murayama N, Russell EJ, Rabin BM. Diagnosis please. Case 17: hypertrophic olivary degeneration secondary to pontine hemorrhage. Radiology. 1999; 213:814–817. PMID: 10580959.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download