Abstract

Neurogenic bladder is common in most spinal cord injury patients. Voiding cystourethrography (VCUG) is recommended in these patients to detect urinary tract complications. However, rare but serious complications may occur during VCUG, although VCUG is generally safe. There are several case reports of bladder rupture occurring in pediatric patients. Here, we report the first case of iatrogenic bladder rupture in an adult spinal cord injury patient in Korea. Particularly, extravasation of contrast without manual instillation has hardly ever been reported. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of bladder rupture without manual instillation during VCUG. We report a case of a 59-year-old female with paraplegia due to tuberculous spondylitis who underwent VCUG as a part of routine evaluation of neurogenic bladder. Extravasation of the contrast media during VCUG developed as a complication and the patient recovered spontaneously without any intervention. Therefore, VCUG should be performed properly in chronic spinal cord injury patients.

Neurogenic bladder is a common complication in most individuals who have a spinal cord injury. The primary goal of neurogenic bladder management in the patients with a spinal cord injury is to maintain adequate bladder drainage, low-pressure urine storage, and low-pressure voiding. Regular periodic follow-up studies, such as voiding cystourethrography (VCUG), are recommended to detect urinary tract complications such as contracted bladder and vesicoureteral reflux [1]. However, rare but serious complications may occur during or after VCUG, although VCUG is generally known to be safe [2].

Till now, there have been several reports about extravasation of material during VCUG, but in most of the cases, extravasation of material occurred in pediatric patients [234]. This might be due to a thin bladder wall and excessive amount of volume infused into the bladder [5]. Here, we report a unique case of extraperitoneal bladder rupture after VCUG in an adult spinal cord injury patient. This case gives a caution while performing VCUG among spinal cord injury patients that the intervention must be performed properly and safely.

A 59-year-old female had aggravated gait disturbance due to progressive right lower extremity weakness 6 months before visiting Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. She had paraplegia due to tuberculous spondylitis from 3-year-old. Since then, she had been walking with the aid of a cane and had some urinary symptoms such as feeling of residual urine and suprapubic discomfort. But as volitional control of voiding is possible, she did not undergo any work up for neurogenic bladder before visiting our hospital.

The severity of her impairment was graded as the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment scale D, level T3 (motor level T3, sensory level T3). The Medical Research Council (MRC) scale was used for the evaluation of muscle strength. The previous MRC grade of hip flexors was 3 before aggravation of the weakness. But as the weakness progressed, the right hip flexor strength was decreased to grade 1, and then, she could not walk with the aid of a cane. On neurologic examination, we observed muscle atrophy, especially in the right lower extremity.

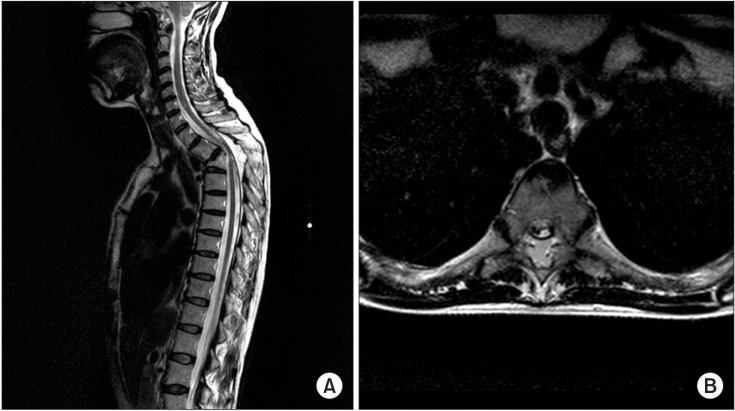

As her gait disturbance had aggravated, she was recommended to undergo a spinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 1). The MRI image showed vertebral body collapse, wedge-shaped deformity, and myelomalacia at the T3 cord level. Radiologic findings were well correlated with her neurologic symptom.

She underwent total laminectomy surgery at the T3 level, partial laminectomy at the T4 level, lipoma removal, and T2–T5 posterolateral fusion using allograft bone. Her right hip flexor strength recovered up to the measured MRC grade 3 after the operation. One week after the surgery, she was transferred from the Department of Neurosurgery to the Department of Rehabilitation.

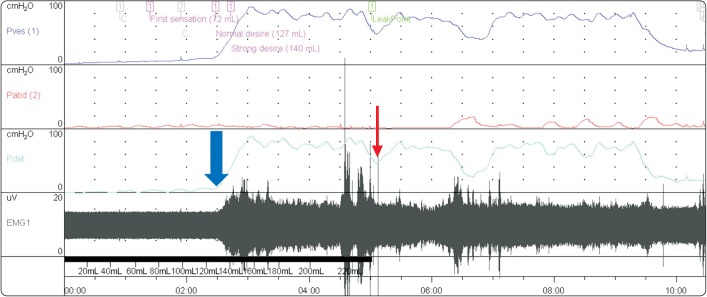

As she could not void without intermittent catheterization, she underwent an urodynamic study just 1 week after the operation (Fig. 2). The detrusor pressure rose abruptly during 127 mL of normal saline infusion (blue arrow), compatible with overactive bladder. The capacity of the bladder was 231 mL at 54 cmH2O, and the compliance of the bladder was 4.3 mL/cmH2O, which is below the average. VCUG performed at that time revealed trabeculation and small capacity of the bladder. At the time of hospital discharge, she was maintained on intermittent catheterization as the amount voided was less than one cup. From that time, she was taking a muscarinic receptor antagonist for the neurogenic bladder, but did not have regular urinary surveillance during 5 years as her home was far away from the hospital.

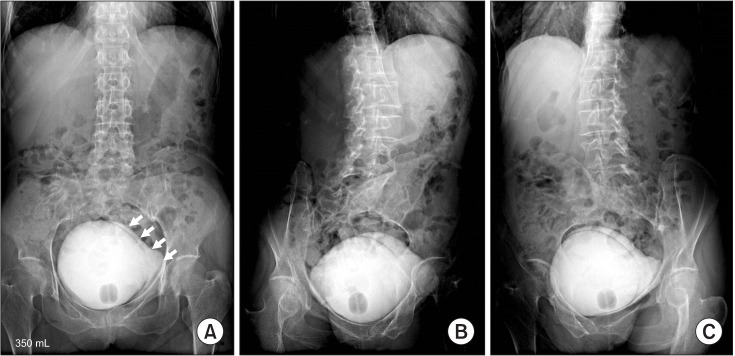

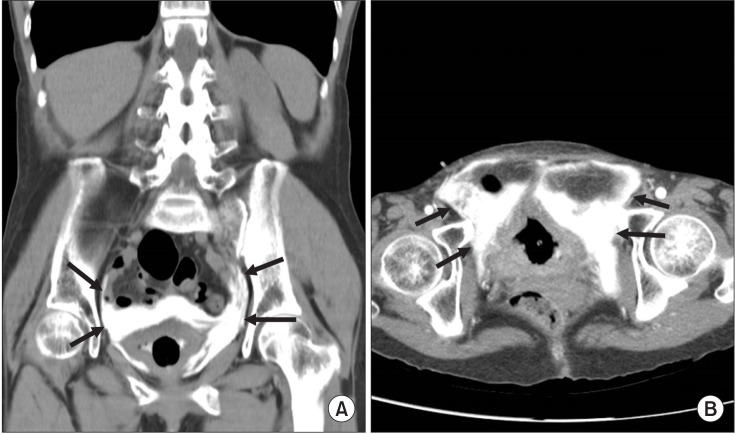

Five years after the operation, as a regular checkup, the patient underwent VCUG at a radiology center without the supervision of a physician. At that time, she was still maintained on intermittent catheterization and was taking a muscarinic receptor antagonist. Contrast media was infused through the indwelling Foley catheter using the gravity drip infusion technique at a height of about 100 cmH2O above the patient. After 250 mL of contrast material had been infused, a plain radiograph revealed extravasation of the contrast material intramurally and into the perivesical soft tissues bilaterally along the lateral aspects of the bladder wall (Fig. 3). Computed tomography (CT) imaging also showed contrast leak into the perivesical and paravesical spaces (Fig. 4). She was referred to an urologist and was recommended to maintain Foley insertion for 2 weeks for bladder resting and to take prophylactic oral antibiotic medication for 1 week. About 2 weeks later, she underwent an additional VCUG to decide whether surgical repair was required, and the findings did not show any extravasation of contrast media in the perivesical and paravesical spaces (Fig. 5). No surgical or medical intervention was given, since extravasation of contrast media was asymptomatic and there was no evidence of leakage.

Non-traumatic bladder rupture is rare, but it mostly occurs in patients with chronically unused bladders and a history of previous surgery. Bladder rupture is divided into intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal bladder rupture. As intraperitoneal bladder rupture occurs because of rapidly rising intraperitoneal pressure, most cases of extravasation of contrast media following VCUG in children show intraperitoneal rupture [4] and require open or laparoscopic surgery. However, the management of extraperitoneal bladder rupture should be individualized, as in our case [6]. Conservative and non-invasive management by placing the urethral catheter with appropriate follow-up is usually enough for recovery from extraperitoneal bladder rupture in the absence of concomitant injuries.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of an asymptomatic extraperitoneal bladder rupture with spontaneous healing without manual instillation in a spinal cord injury patient. In most other cases, forceful pushing of the contrast media into the bladder by the hand-injection method without precaution caused abrupt distention of the contracted bladder and damaged the bladder mucosa. But in this case, bladder rupture occurred due to infusion via gravity force, not due to manual instillation. Extravasation of contrast media associated with VCUG usually occurs in adults in instances of chronically unused bladders such as chronic renal failure [7]. The ability of the detrusor muscle to adjust its contractile tension (tone) and to accommodate varying volumes without increasing the intravesical pressure is maintained via the normal process of filling and emptying the bladder. The histochemical studies of dysfunctional bladder revealed connective tissue change and it is correlated with the dynamic analysis of bladder compliance [8]. Altered bladder compliance is also common in spinal cord injury patients, and these patients and chronic renal failure patients may have similar characteristics. Hackler et al. [9] reported low compliance in 10% of patients with suprasacral injuries and in 50% of patients with sacral injuries among spinal cord injury patients. Bladder compliance can be calculated by using the following formula: change in volume divided by change in detrusor pressure. Therefore, the bladder pressure in chronic spinal cord injury patients with neurogenic bladder changes abruptly, even with a small volume change. This case shows that bladder rupture can occur when an excess volume (250 mL) is instilled more than the expected volume (231 mL) even without manual instillation. There are some proposed principles for a neurogenic case of contracted bladder during VCUG. First, the contrast material should be instilled using the gravity method with the container placed no higher than 60 cm above the patient's level [3]. Second, physicians must stop the drip and drain the contrast media if sudden headache occurs or rising of blood pressure develops [10]. Third, if an urodynamic study or VCUG has been performed previously, the examiner should check the estimated volume of the bladder.

There are several formulas for assessing the bladder capacity in children under 2 years of age [4]. But there is no formula for assessing dysfunctional bladder volume in adults. Therefore, further study should be performed for detecting the tolerable volume of neurogenic bladder during VCUG in adults, especially for the unused bladder.

In conclusion, rehabilitation physicians and radiologists should pay attention to the setting when VCUG is being performed in spinal cord injury patients, and they should assess the risk of overestimating bladder capacity.

References

1. Perkash I. Long-term urologic management of the patient with spinal cord injury. Urol Clin North Am. 1993; 20:423–434. PMID: 8351768.

2. McAlister WH, Cacciarelli A, Shackelford GD. Complications associated with cystography in children. Radiology. 1974; 111:167–172. PMID: 4593165.

3. Wosnitzer M, Shusterman D, Barone JG. Bladder rupture in premature infant during voiding cystourethrography. Urology. 2005; 66:432.

4. Keihani S, Kajbafzadeh AM. Bladder rupture after voiding cystourethrography: a case report and literature review on pitfalls and bladder volume estimation. Can Urol Assoc J. 2015; 9:E826–E829. PMID: 26600895.

5. Kajbafzadeh AM, Saeedi P, Sina AR, Payabvash S, Salmasi AH. Infantile bladder rupture during voiding cystourethrography. Int Braz J Urol. 2007; 33:532–535. PMID: 17767759.

6. Santucci RA, McAninch JW. Bladder injuries: evaluation and management. Braz J Urol. 2000; 26:408–414.

7. Matsumoto AH, Clark RL, Cuttino JT Jr. Bladder mucosal tears during voiding cystourethrography in chronic renal failure. Urol Radiol. 1986; 8:81–84. PMID: 3538606.

8. Landau EH, Jayanthi VR, Churchill BM, Shapiro E, Gilmour RF, Khoury AE, et al. Loss of elasticity in dysfunctional bladders: urodynamic and histochemical correlation. J Urol. 1994; 152:702–705. PMID: 8021999.

9. Hackler RH, Hall MK, Zampieri TA. Bladder hypocompliance in the spinal cord injury population. J Urol. 1989; 141:1390–1393. PMID: 2724437.

10. Kovindha A, Sivasomboon C, Ovatakanont P. Extravasation of the contrast media during voiding cystourethrography in a long-term spinal cord injury patient. Spinal Cord. 2005; 43:448–449. PMID: 15741977.

Fig. 1

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) images showing T3 vertebral body collapse and wedge-shaped deformity in coronal (A) and central canal stenosis with spinal cord atrophy at the T3 level in axial MRI (B).

Fig. 2

Urodynamic study reveals vesical pressure rising during 127 mL of contrast infusion (blue arrow) and the bladder capacity was 231 mL at 54 cmH2O (red arrow).

Fig. 3

Initial voiding cystourethrography showing extraperitoneal contrast material (short arrows) on anteroposterior view (A), right oblique view (B), and left oblique view (C).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download