Abstract

Wernicke encephalopathy (WE) is a neurologic disorder characterized by clinical symptoms, such as nystagmus, ataxia, and mental confusion. Hypothermia in patients with WE is a rare complication, and its pathogenic mechanism and therapy are yet to be ascertained. Herein, we presented a case of a 61-year-old man who was diagnosed with WE 3 months earlier. We investigated the cause of hypothermia (35.0℃) that occurred after an enema (bowel emptying). Brain magnetic resonance imaging revealed mammillary body and hypothalamus atrophy. In the autonomic function test, the sympathetic skin response (SSR) test did not evoke SSR latencies on both hands. In addition, abnormal orthostatic hypotension was observed. Laxative and stool softener medication were administered, and his diet was modified, which led to an improvement in constipation after 2 weeks. Moreover, there was no recurrence of hypothermic episode. This is the first reported case of late-onset hypothermia secondary to WE.

Wernicke encephalopathy (WE) is a neurologic disorder characterized by thiamine deficiency-induced clinical symptoms, such as nystagmus, ataxia, and mental confusion [1]. WE is diagnosed by typical clinical symptom triad with chronic alcoholism history. Further, the diagnosis can be confirmed by mitigation of the symptoms by thiamine supplementation.

Hypothermia in patients with WE is a rare complication, and its pathogenic mechanism and therapy are yet to be ascertained [2]. To the best of our knowledge, hypothermia in the chronic state of WE has not been previously reported. Herein, we reported one such case with WE along with a literature review.

A 61-year-old man who was a chronic alcoholic with daily 2-bottle drinking history for 30 years was referred to the rehabilitation department of Seoul Medical Center 3 months after being diagnosed with WE. In the acute period, he showed typical clinical symptoms of WE such as ataxia, nystagmus, and memory disturbance. After oral administration of thiamine 300 mg/day, symptoms showed some improvement, but memory disturbance persisted.

The patient was admitted to the rehabilitation unit. At admission, he showed severe constipation with defecation 1 or 2 times a week. We prescribed laxative and stool softener medicine, but his constipation was not improved. Hence, glycerin enema was conducted. After the enema, the patient experienced chilling and sweating sensation for 1–2 minutes and his body temperature dropped to 35.0℃. During the hypothermic episode, blood pressure, pulse rate, and respiration rate were 110/70 mmHg, 76/min, and 20/min, respectively; and blood sugar level was in the normal range. Hypothermia showed improvement through passive rewarming (blanket covering) and active rewarming (intravenous heating fluid).

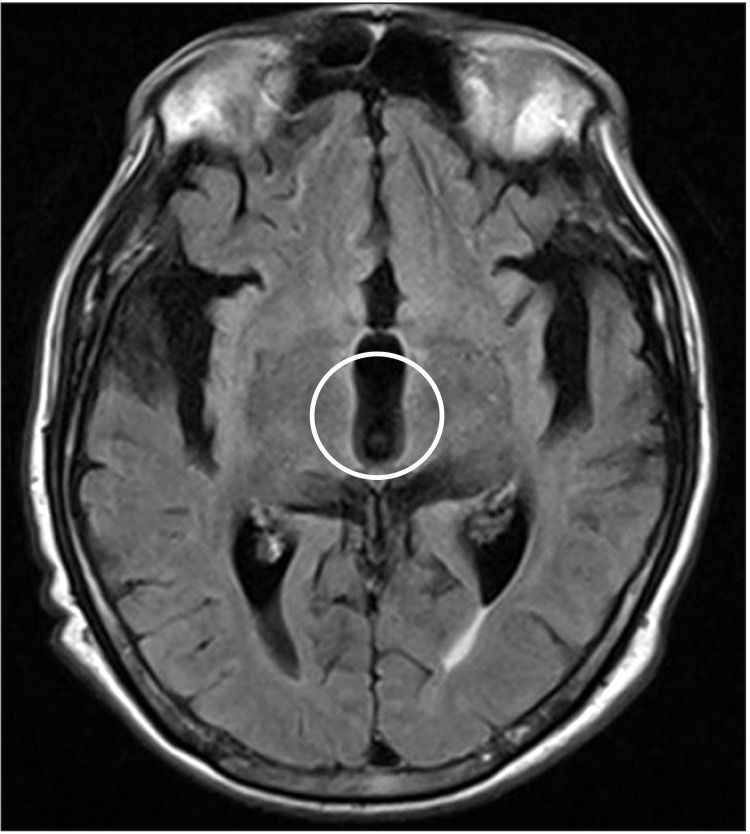

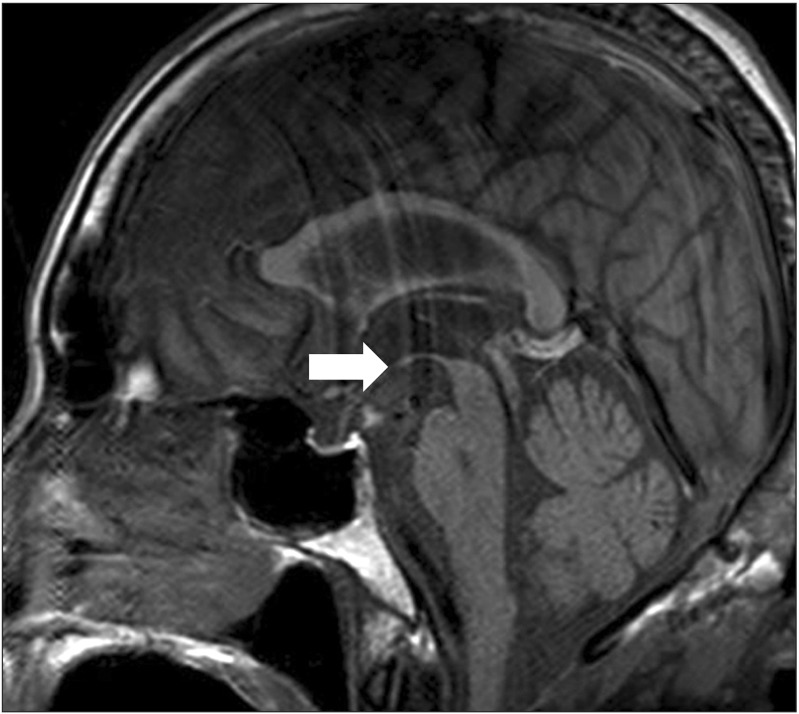

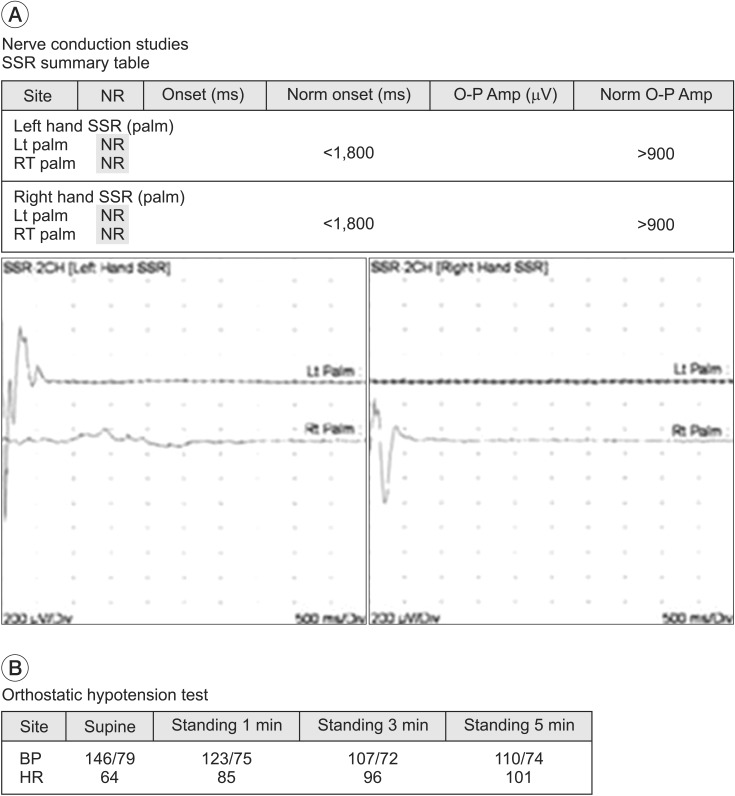

To investigate the cause of hypothermia, we reviewed his medical history, which showed no hypothermia-related medication. His thiamine level and thyroid function test was normal. In addition, there were no infectious signs. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed. Axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery T2-weighted image showed diffuse 3rd ventricle enlargement with hypothalamus atrophy (Fig. 1). Sagittal T1-weighted image showed atrophy in the mammillary body and hypothalamus, the known thermo-regulator (Fig. 2). In the autonomic function test, sympathetic skin response (SSR) was obtained with a Sierra Wave EMG system (Cadwell Laboratories Inc., Kennewick, WA, USA); the SSR test did not evoke SSR latencies on both hands. Abnormal orthostatic hypotension was observed with a systolic blood pressure drop of up to 39 mmHg caused by sudden rising from recumbent position (Fig. 3).

Despite medication for severe constipation, his symptom was not improved. In order to prevent a second hypothermic episode, we did a warm (36.0℃) glycerin enema procedure. Room temperature was maintained at 24.0℃. Nevertheless, a second hypothermic episode occurred. We added more laxative and stool softener medicine, and modified his diet with high fiber. Consequently, his constipation improved after 2 weeks and there was no recurrence of hypothermic episode.

Hypothermia is a rare complication in WE [345]. In a study by Victor et al. [3], only 2 cases (0.8%) showed symptoms of hypothermia among 245 patients with WE. Philip and Smith [6] reported 3 cases of hypothermia among WE patients and in a study by Harper et al. [4], hypothermia occurred in 5 cases (approximately 4%) of 131 patients with WE. While all the above studies showed hypothermia at an early state of WE, hyperthermia could appear in the late stages of WE [2]. However, there are no previous reports on late-onset hypothermia at 3 months after the treatment for WE.

The mechanism of hypothermia in WE remains unclear. It might result from dysfunction of the posterior hypothalamus, which is the center of temperature regulation [2]. The hypothalamus is responsible for thermoregulation in humans, and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) and endocrine system are responsible for the initial and late stage of thermoregulation [7]. Dysfunction of the ANS has been verified in cases of WE [5] and ANS dysfunction could be a cause of hypothermia. Jung et al. [8] reported impaired ANS response in patients with chronic alcoholism compared to non-alcoholic group, based on the ANS test (SSR, heart rate variability). Likewise, our case also showed an abnormal SSR response and orthostatic hypotension. Hypothermic episode appeared post-glycerin enema treatment for severe constipation. We checked the room temperature, medical history, and other laboratory findings, such as thyroid function test or infection marker to exclude the possibility of hypothermia due to other causes. Brain MRI in our patient indicated hypothalamus and mammillary body atrophy. Based on these evaluations, the cause of hypothermia was due to abnormal function of ANS and atrophy of the hypothalamus in the brain, which is responsible for thermo-regulation.

Hypothermia is associated with high mortality rates in WE. Ackerman reported seven cases of WE with hypothermia [9]. In acute state of WE, four patients were treated with thiamine, of which, three survived and returned to normal body temperature. Three of seven cases were not treated with thiamine, and all died. Contrary to the previous case reports, despite adequate thiamine treatment in acute state and maintaining oral thiamine in chronic state, we observed late-onset hypothermic episode. Thus, further study is needed to determine the cause or mechanism of hypothermia in chronic WE patients.

This case report has several limitations. First, we could not measure the core temperature. It was difficult to measure the rectal temperature due to the occurrence of hypothermia post-enema, therefore, the axillary temperature was measured instead. Second, among autonomic function tests, heart rate variability was not measured due to the deterioration of the patient's cognitive function and deep breathing and Valsalva maneuver were unsuccessful.

In conclusion, to our best knowledge, this is the first reported case of late-onset hypothermia secondary to WE. In case of hypothermic episode in the chronic state of WE, evaluation of autonomic function test or brain imaging study to detect lesion of the hypothalamus is recommended. If other causes of hypothermia including endocrine problem, medication, cold environment, or infection are ruled out, minimizing hypothermia-inducing factors and active clinical management are required.

References

1. Ropper AH, Samuels MA, Klein JP. Chapter 41. Diseases of the nervous system caused by nutritional deficiency. Adams and Victor's principles of neurology. 10th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education;2014. p. 1161–1185.

2. Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke's encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007; 6:442–455. PMID: 17434099.

3. Victor M, Adams RD, Collins GH. Chapter 2. Clinical finding. The Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome and related neurologic disorders due to alcoholism and malnutrition. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis;1989. p. 11–29.

4. Harper C. The incidence of Wernicke's encephalopathy in Australia: a neuropathological study of 131 cases. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1983; 46:593–598. PMID: 6886695.

5. Thorarinsson BL, Olafsson E, Kjartansson O, Blondal H. Wernicke's encephalopathy in chronic alcoholics. Laeknabladid. 2011; 97:21–29. PMID: 21217196.

6. Philip G, Smith JF. Hypothermia and Wernicke's encephalopathy. Lancet. 1973; 2:122–124. PMID: 4124044.

7. Danzl DF. Hypothermia and frostbite. In : Kasper DL, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J, editors. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 19th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education;2015. Chapter 478e.

8. Jung TH, Park DS, Nam HS, Jung HO, Lee SE, Kim DH. Autonomic function in chronic alcoholic patients. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2009; 33:321–326.

9. Ackerman WJ. Stupor, bradycardia, hypotension and hypothermia: a presentation of Wernicke's encephalopathy with rapid response to thiamine. West J Med. 1974; 121:428–429. PMID: 4460385.

Fig. 1

Magnetic resonance imaging of a 61-year-old man with mental confusion, ataxic gait, ocular symptoms and hypothermia. Axial fluid attenuated inversion recovery T2-weighted image showed diffuse 3rd ventricle enlargement with hypothalamus atrophy (circle).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download