Abstract

Objective

To investigate the shoulder disease patterns for the table-tennis (TT) and archery (AR) wheelchair athletes via ultrasonographic evaluations.

Methods

A total of 35 wheelchair athletes were enrolled, made up of groups of TT (n=19) and AR (n=16) athletes. They were all paraplegic patients and were investigated for their wheelchair usage duration, careers as sports players, weekly training times, the Wheelchair User's Shoulder Pain Index (WUSPI) scores and ultrasonographic evaluation. Shoulders were divided into playing arm of TT, non-playing arm of TT, bow-arm of AR, and draw arm of AR athletes. Shoulder diseases were classified into five entities of subscapularis tendinopathy, supraspinatus tendinopathy, infraspinatus tendinopathy, biceps long head tendinopathy, and subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis. The pattern of shoulder diseases were compared between the two groups using the Mann-Whitney and the chi-square tests

Results

WSUPI did not significantly correlate with age, wheelchair usage duration, career as players or weekly training times for all the wheelchair athletes. For the non-playing arm of TT athletes, there was a high percentage of subscapularis (45.5%) and supraspinatus (40.9%) tendinopathy. The percentage of subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis showed a tendency to be present in the playing arm of TT athletes (20.0%) compared with their non-playing arm (4.5%), even though this was not statistically significant. Biceps long head tendinopathy was the most common disease of the shoulder in the draw arm of AR athletes, and the difference was significant when compared to the non-playing arm of TT athletes (p<0.05).

Conclusion

There was a high percentage of subscapularis and supraspinatus tendinopathy cases for the non-playing arm of TT wheelchair athletes, and a high percentage of biceps long head tendinopathy for the draw arm for the AR wheelchair athletes. Consideration of the biomechanical properties of each sport may be needed to tailor specific training for wheelchair athletes.

The total number of disabled persons of Korea was 2.73 million people in 2014, and it reflects an increased value of 27.5% over the last 10 years. The interest in sports for the disabled has also been increasing in proportionate, as to enhance the quality of life for this group [1]. In Korea, many wheelchair users prefer participating both in table-tennis (TT) and archery (AR) sports, with the former being the event with the most registered players (1,393 disabled persons), and the latter being popular as it has had consistently good grades for competition at the Paralympic games. The wheelchair users, however, are prone to musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limbs resulting from overuse injuries, from causes such as weight-bearing, transfer, and wheelchair propulsion as compensation for the paralyzed lower limbs [2]. In such situations, the activity for the disabled sports can rather cause secondary musculoskeletal damage to the upper limbs of the wheelchair users [3]. Both wheelchair versions of TT and AR can thus be representative sports to investigate the effect of sport activity on musculoskeletal diseases, as there is a correlation with prolonged use of the wheelchair and incidence of these disorders, and also there are considerable numbers of registered players for the two events [4].

It is important for the players of TT to understand the dynamics to increase the racket speed and to bring about a more quick desired movement for the ball [5]. However, it is known that the impingement syndrome of shoulder often occurs in able-bodied athletes of TT [6]. Also, for the able-bodied athletes of AR, shoulder diseases that correlated with the motion of retraction have been reported [78]. This is because for AR, it is essential to maintain the static balance of the body and to minimize the tremor of muscles of upper limbs for effective targeting and shooting [9]. There have only been few reports on the differences on shoulder morbidity between wheelchair TT and AR athletes, as the two sports have distinct biomechanical properties. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there is yet no research on whether the patterns of musculoskeletal diseases of disabled athletes are different from those for the able-bodied ones in the same event.

Although some reports have been made for disabled sports-related injuries after the Paralympic competitions, they have been limited to descriptive studies [1011], or they have largely focused on wheelchair athletes without a distinction to the individual events [1213]. Recently, Lim et al. [14] found that subscapularis and supraspinatus tendinopathies were the most common shoulder morbidities in the poliomyelitis wheelchair basketball players; however, comparison with other events was not conducted. In a study for Slovenian players, Kondric et al. [15] reported that table tennis players suffered fewer injuries than players for other racket events, such as tennis and badminton; however, the results were not accompanied by precise imaging examinations. As such, studies using imaging tools have not reported on patterns of shoulder disease according to each event, as they are known to inevitably occur in wheelchair athletes [16].

In this study, we investigated shoulder morbidities through ultrasonographic evaluation for the wheelchair TT and AR athletes, the two representative sports for the domestic disabled. Ultrasound is known to be a highly sensitive imaging tool for the assessment of rotator cuff structure in the shoulder, and it has no risk of exposure to radiation [17]. Using this ultrasound, the present study aimed to compare the pattern of shoulder diseases between the two events, and between the dominant side and non-dominant side shoulder.

Two groups of wheelchair athletes were enrolled from March to May 2015, representing a group of athletes for wheelchair TT and AR. They were all in the regular training program at the disabled training centers, based in Suwon and Incheon. A total of 35 wheelchair athletes were recruited, 19 representing TT and 16 AR. Subjects were excluded when they had a history of surgical treatment for injuries to the upper extremity, a history of visiting a clinic for shoulder pain during the last 6 months, an unwillingness to participate in this research or when the main means of their transportation was not a manual wheelchair.

In order to participate in the wheelchair sports, disabled players are granted a rating based on their disability through the classification and registration as athletes in each association for each event [18]. In case of sitting classification for TT, a total of five classes are available, determined according to the neurological level of the athlete's spinal cord injury [19]. The class 1 of TT (TT1) is a rating when the injury is of C6 or higher level, and for which the muscle grade for the elbow extensors of playing arm is less than fair, so the player cannot return a ball accurately to the opponent using the skill of backhand push. The class 2 of TT (TT2) is a rating when the injury is of C7 or C8 level, with the muscle grade for the finger flexor or abductors of playing arm being less than fair, so as the athlete cannot grip a racket firmly, and would need a strap or bandage. The class 3 of TT (TT3) is a rating when the neurological level injury is from T1 to T8 level, with the sitting balance related with trunk muscles being less than fair, and there is a need for a waist belt securing the body to the wheelchair for competition. The class 4 (TT4) is for a player whose injury is from T9 to L1 level, and for whom the sitting balance is fair or good, and the class 5 (TT5) is a rating when the neurological level of injury is L2 or lower, with the athlete having a normal sitting balance. Players with other kinds of disabilities, who cannot play in standing position, are granted a rating in accordance with this standard.

In case of sitting classification for AR players, the disability ratings are in two classes, class 1 (AR1) and class 2 (AR2), in accordance with having quadriplegia and paraplegia, respectively, and criteria that are relatively simple compared to that for wheelchair TT [20]. This study was planned to investigate the direct effects of each event on the shoulder of wheelchair athletes, so only included paraplegic players of class TT3, TT4, TT5 for table-tennis and AR2 for archery, and the classes having difficulty commanding precise skills for each event were excluded, due to the dysfunctional upper extremity itself. The present study was approved by the local ethics committee and all subjects gave informed consent, after receiving an explanation about the purpose, method, and policy for the personal information collected from this study.

First, through a preliminary questionnaire, all of the subjects were investigated for an operation history for the upper extremity including shoulder. In addition, in the questionnaire, the shoulder status of whether being painful or not, duration and severity of pain, age, time of the onset for disability, duration for wheelchair usage, career as players, and weekly training schedules were surveyed. The neurological level and amputation level were checked for athletes of spinal cord injury and amputees, respectively, and the class to which the player belonged to was identified for each event. We measured the Wheelchair User's Shoulder Pain Index (WUSPI) to quantify the degree of shoulder pain for which the wheelchair athlete felt during daily living. WUSPI was composed of 15 items, and each individual item was scored on the basis of visual analogue scale from 0 to 10 points, for a total of 150 points, with a higher score representing more serious pain, per each activity for daily living [21].

Second, to evaluate the status of muscle and tendon constituting the rotator cuff of shoulder, ultrasonographic evaluation was conducted by one physiatrist with more than 5 years of experience in musculoskeletal ultrasonography and blinded on the information for each athlete. We performed real-time ultrasonography using a portable HM70A ultrasound machine (Medison, Seoul, Korea) interfaced with 12-MHz linear array transducer. The subjects underwent ultrasound sitting in a chair without a back after changing into comfortable clothes, and bilateral sides of their shoulder were examined in all subjects.

For TT wheelchair athletes, ultrasonographic evaluation was conducted at the shoulder of the playing arm holding a racket, and then contra-laterally at the shoulder of the non-playing arm corresponds with the shoulder of general wheelchair users. For AR wheelchair athletes, bilateral shoulder were ultrasonographically evaluated for the bow arm and the draw arm, holding a bow and pulling an arrow, respectively, to identify and compare the pattern for the existing, possible disorders for each shoulder.

For the ultrasonographic evaluation, the subject was asked to keep an arm close to the body, flex an elbow to 90°, and to place a hand palm up in supination on his leg during the sitting position. In that posture, the transducer was placed in the axial plane on the subject, and the biceps long head tendon, leading through a rotator cuff interval, was examined within a biceps groove. The subject was then asked to rotate the shoulder externally in order to examine the subscapularis tendon. After that, the subject was instructed to place their hand on the ipsilateral hip area through extension and internal rotation of shoulder (modified Crass position) for evaluation of supraspinatus tendon and subacromial-subdeltoid bursa. Finally, while asking the subject to hold the contralateral shoulder with their ipsilateral hand, the transducer was placed on the posterior surface of shoulder in the longitudinal plane for examination of infraspinatus tendon and glenoid labrum, and in the oblique plane for the teres minor tendon [22].

A tendinopathy was recognized when the partial or full thickness tear, or calcification was identified clearly in both the short and long axis for subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor tendons. For the biceps long head tendon, enveloped by articular synovium within the biceps groove, it was evaluated whether there was a tenosynovitis as with collection of fluid in the surrounding region, tendinopathy with tendon rupture, or other abnormalities such as subluxation. The subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis was defined as being present when the thickness of the bursa, between deltoid and supraspinatus, was 2 mm or over [23].

All the statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 19.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Variables between the two groups were tested for significance using the Mann-Whitney test or chi-square test, as appropriate. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the correlation between the WSUPI and other variables. Shoulders were divided into the playing arm of TT, non-playing arm of TT, bow arm of AR, and draw arm of AR, and the pattern of shoulder diseases for each shoulder were compared using the chi-square test. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 for all the tests.

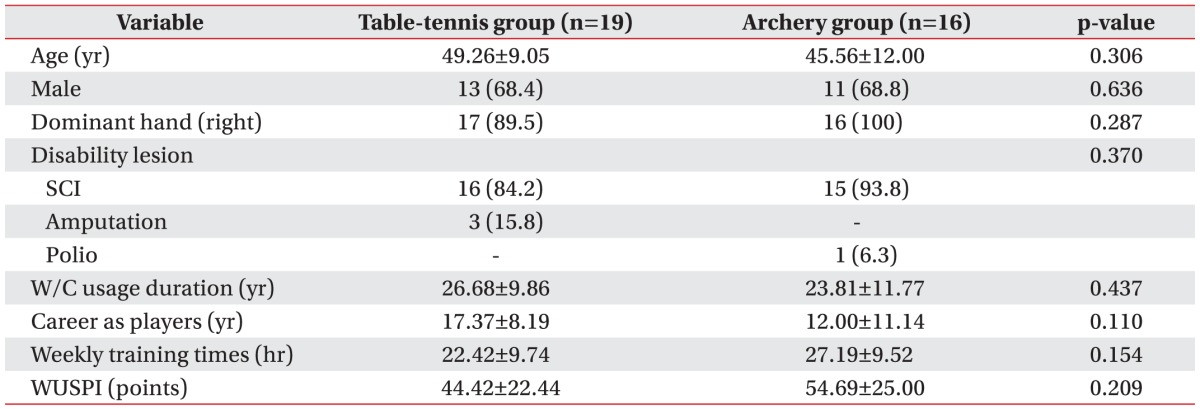

The mean age of the wheelchair athletes of TT and AR was 49 years and 45 years, respectively. For the total 19 athletes of TT, 13 players (68.4%) were men. Also, for the 19 TT athletes, 17 players (89.5%) were right handed. In the total of 16 athletes of AR, 11 players (68.8%) were men and all of the players (100%) were right handed. The athletes with a spinal cord injury included 16 players (84.2%) for TT and 15 players (93.8%) for AR. Age, the ratio of dominant hand and the proportion of players with spinal cord injury were not statistically different between the two groups. There were no significant differences for the duration of wheelchair usage, the career as players, the weekly training times, and the WUSPI (26.68 vs. 23.81 years, 17.37 vs. 12.00 years, 22.42 vs. 27.19 hours, and 44.42 vs. 54.49 points, respectively) between the two groups (Table 1).

With respect to the correlation between WUSPI and the other variables, the correlation coefficients were 0.152, (p=0.361), 0.104 (p=0.534), –0.101 (p=0.548), and –0.027 (p=0.872) for age, duration of wheelchair usage, career as players, and their weekly training times, respectively.

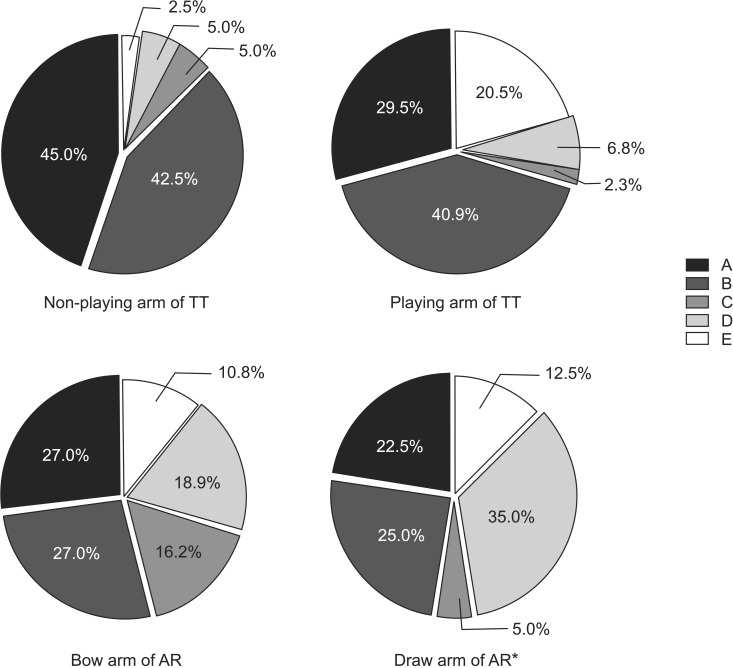

Through ultrasonographic evaluation in the group of TT, the mean number of rotator cuff related diseases was found to be 2.18 and 2.32 for playing-arm and non-playing arm, respectively, higher in the shoulder of the playing arm than the non-playing arm; however, the differences were not significant. We examined the pattern of shoulder diseases for each side. In case of the non-playing arm shoulders, among the total 40 known diseases, the percentage of subscapularis and supraspinatus tendinopathy was high, and the percentage was relatively low for infraspinatus tendinopathy, biceps long head tendinopathy, and subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis. In case of the playing arm shoulders, among the total 44 diseases, there were tendencies for decreased percentage of subscapularis and increasing percentage of subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis, even though statistically non-significant, as compared with the non-playing arm (Fig. 1).

In the AR group, the mean number of rotator cuff related diseases was found to be 2.29 and 2.35 for the bow arm and the draw arm, respectively. For the shoulder of the bow arm, among the total 37 diseases, the percentage of subscapularis and supraspinatus tendinopathy was high, and those were followed by the percentage of biceps long head tendinopathy, infraspinatus tendinopathy, and subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis in decreasing order. In case of the shoulder for the draw arm, among the total 40 diseases, the percentage of biceps long head tendinopathy was highest, and it was followed by supraspinatus tendinopathy and subscapularis tendinopathy in decreasing order; however, the differences for these patterns were not statistically significant. With integrated analysis for TT and AR, the biceps long head tendinopathy was the most common disease of shoulder in draw arm of AR, and the difference was significant as compared to the non-playing arm of TT, which showed a higher prevalence of subscapularis and supraspinatus tendinopathy (p<0.05) (Fig. 1).

When comparing the 31 players with spinal cord injury and 3 players as amputees, the percentage of supraspinatus tendinopathy, subscapularis tendinopathy, and biceps long head tendinopathy was 34.3%, 31.4%, and 16.4%, respectively, in the group of spinal cord injury. Among the group of amputees, the percentage of supraspinatus tendinopathy, subscapularis tendinopathy, and subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis was 37.5%, 31.3%, and 18.8%, respectively. However, there was no significant difference in the distribution of the diseases between the two groups.

The aim of this study was to investigate shoulder morbidities through ultrasonographic evaluation in the wheelchair TT and AR athletes, and demonstrated that there were differences in the pattern of shoulder diseases per each event. Moreover, even within same event, the patterns were found to be different between the dominant side and non-dominant side shoulder.

It has been demonstrated that the most common diseases of the shoulder for the non-playing arm were the subscapularis and supraspinatus tendinopathies, and were of high prevalence with 86.4% for the sum of the two morbidities among the wheelchair TT athletes. This sum of these two tendinopathies showed overall high prevalence, ranked from high to low, in the playing-arm of TT players, the bow arm of AR, and the draw arm of AR, as 68.0%, 54.0%, and 47.5%, respectively. These results are consistent with previous studies suggesting that the prevalence of rotator cuff tendinopathy related to shoulder adduction and internal rotation, which were prone to overuse injuries during transfer and wheelchair propulsion, and high among the wheelchair users [1314]. Kerr et al. [24] reported in their study of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in the weight-bearing shoulder for wheelchair users that the morbidity related to rotator cuff occurred primarily at the anterosuperior side including subscapularis and supraspinatus tendons, and this corresponds with our results.

An important finding of our study was that the prevalence of biceps long head tendinopathy was higher than subscapularis or supraspinatus tendinopathy for the shoulder in draw arm of AR, which was the most significant difference as compared with the non-playing arm of TT. In the study conducted with the able-bodied athletes of AR, Shinohara et al. [25] reported that the angle of elbow flexion in the shoulder impingement group was significantly smaller than that for the uninjured group, indicating that the abnormality of biceps long head tendon, regarding the function as the elbow flexor and a component making up the rotator cuff interval, could affect shoulder pain as well as sustaining elbow flexion. It is known that for the Korean national archery team, in their training program, there is emphasis on the side-to-side balance at the level of shoulder during pulling of the bow-string to its maximum, just before shooting the arrow [26]. It is presumed that in order to maintain a stable balance between the bilateral shoulders, the eccentric contraction of biceps brachii might be a principal factor in maintaining a constant force in the draw arm at the state of pulling the bow-string.

In case of the TT athletes, our results demonstrated that the prevalence of subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis was higher among this group, particularly for their playing arm side than the non-playing arm side, and this is suggestive of shoulder impingement syndrome. This finding is in agreement with a previous study where the shoulder internal rotation torque exerted by advanced players was found to be significantly larger than that exerted by the intermediate players due to their more powerful forehand top-spin skill [5]. In other words, shoulder impingement syndrome can occur for the faster and stronger contraction of the supraspinatus to enhance the torque for internal rotation.

There has been controversy on whether sports activity could be a preventive factor for shoulder morbidities or whether it could be a risk factor for over-use injuries for the wheelchair users. One study reported that enhancing the power and endurance of muscle might prevent the degeneration of the shoulder joint for wheelchair athletes [27], and the other report indicated that the risk of having shoulder pain was higher in non-athletes than wheelchair athletes [28]. However, Brose et al. [13] described shoulder pain increasing with age, and Akbar et al. [3] reported that the prevalence for rotator cuff-related pain was higher among wheelchair users doing sports activities than the non-sport group. In our study, WSUPI was not found to be significantly correlated with age, wheelchair usage duration, career as players and weekly training times for all subjects among the wheelchair athletes; that is to say that the musculoskeletal diseases of the upper extremity did not increase in proportion of duration of wheelchair use or the weekly training times. These results were commonly found in both TT and AR groups, even though the biomechanical characteristics of the two sports are different. It may be assumed that there could have been differences between our results and previous studies where whole groups of wheelchair athletes were compared with the non-athletic wheelchair users. Differences between comparisons across the groups versus comparison of the contralateral shoulders in the same individual may arise if the wheelchair athletes take care of both their shoulders through a combined program of stretching, strengthening and relaxation, protecting both their shoulders from pain or worsening of pain.

Taken together, this study suggests that the wheelchair athletes of AR could find a way to prevent injuries and enhance performance, by means of strengthening the eccentric contractility for the biceps brachii of their draw arm. Also for wheelchair athletes of TT, exercises for scapular stabilization and supraspinatus flexibility need to be emphasized to prevent injuries from the impingement syndrome. The wheelchair users need to maintain exercise activities for improved physical and mental health [3], and it is important to have the skill for handling their wheelchair but also understand the characteristics of each sporting event relevant to their condition [2930]. Our results are expected to aid in event-specific treatments and training programs. We postulate that it is feasible to present a way of maximizing the benefits of exercise, while minimizing the risk for secondary injury with exercise routines considering the status of the shoulder for the wheelchair athlete and the biomechanical property of the event they choose to participate in. Further investigation will be needed confirm the validity of such training methods.

The present study was limited by its small number of participants. In the future, a comparative study with ablebodied wheelchair athletes will be necessary to evaluate more objectively the pattern of shoulder morbidities according to each event. Also, a follow-up study for comparison of athletes having a history of surgical treatment, having visited a clinic for shoulder pain recently, or with more disabling tetraplegia may be able to draw on the fundamental conclusions emerged from this pilot in analyzing the specific compensatory mechanisms for the painful or the paralyzed limitation of the upper limb motion in a competition setting.

In conclusion, our study demonstrated that the prevalence of biceps long head tendinopathy was highest for the draw arm shoulder of AR wheelchair athletes, while that for subscapularis or supraspinatus tendinopathy was high for the non-playing arm shoulder of TT wheelchair athletes, suggesting that there were differences for the pattern of shoulder diseases for each event. It would be necessary to consider the pattern of pain, correlated with basic wheelchair usage as well as event-specific biomechanical differences, during the medical examination of the shoulder of wheelchair athletes.

References

1. Korean Statistical Information Service [Internet]. Daejeon: Korean Statistical Information Service;c2015. cited 2016 Jul 22. Available from: http://kosis.kr/.

2. McCasland LD, Budiman-Mak E, Weaver FM, Adams E, Miskevics S. Shoulder pain in the traumatically injured spinal cord patient: evaluation of risk factors and function. J Clin Rheumatol. 2006; 12:179–186. PMID: 16891921.

3. Akbar M, Brunner M, Ewerbeck V, Wiedenhofer B, Grieser T, Bruckner T, et al. Do overhead sports increase risk for rotator cuff tears in wheelchair users? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015; 96:484–488. PMID: 25449196.

4. Korea Paralympic Committee [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Paralympic Committee;c2015. cited 2016 Jul 22. Available from: http://www.koreanpc.kr/.

5. Iino Y, Kojima T. Kinetics of the upper limb during table tennis topspin forehands in advanced and intermediate players. Sports Biomech. 2011; 10:361–377. PMID: 22303787.

6. Pieper HG, Quack G, Krahl H. Impingement of the rotator cuff in athletes caused by instability of the shoulder joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1993; 1:97–99. PMID: 8536016.

7. Park JY, Oh KS, Yoo HY, Lee JG. Case report: Thoracic outlet syndrome in an elite archer in full-draw position. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013; 471:3056–3060. PMID: 23430722.

8. Naraen A, Giannikas KA, Livesley PJ. Overuse epiphyseal injury of the coracoid process as a result of archery. Int J Sports Med. 1999; 20:53–55. PMID: 10090463.

9. Lin JJ, Hung CJ, Yang CC, Chen HY, Chou FC, Lu TW. Activation and tremor of the shoulder muscles to the demands of an archery task. J Sports Sci. 2010; 28:415–421. PMID: 20432134.

11. Webborn N, Emery C. Descriptive epidemiology of Paralympic sports injuries. PM R. 2014; 6(8 Suppl):S18–S22. PMID: 25134748.

12. van der Woude LH, Bouten C, Veeger HE, Gwinn T. Aerobic work capacity in elite wheelchair athletes: a cross-sectional analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002; 81:261–271. PMID: 11953543.

13. Brose SW, Boninger ML, Fullerton B, McCann T, Collinger JL, Impink BG, et al. Shoulder ultrasound abnormalities, physical examination findings, and pain in manual wheelchair users with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008; 89:2086–2093. PMID: 18996236.

14. Lim KB, Yoo J, Lee HJ, Lee JH, Kwon YG. Evaluation of pain and ultrasonography on shoulder in poliomyelitis wheelchair basketball players. Korean J Sports Med. 2014; 32:20–26.

15. Kondric M, Matkovic BR, Furjan-Mandic G, Hadzic V, Dervisevic E. Injuries in racket sports among Slovenian players. Coll Antropol. 2011; 35:413–417. PMID: 21755712.

16. Akbar M, Balean G, Brunner M, Seyler TM, Bruckner T, Munzinger J, et al. Prevalence of rotator cuff tear in paraplegic patients compared with controls. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010; 92:23–30. PMID: 20048092.

17. Fischer CA, Weber MA, Neubecker C, Bruckner T, Tanner M, Zeifang F. Ultrasound vs. MRI in the assessment of rotator cuff structure prior to shoulder arthroplasty. J Orthop. 2015; 12:23–30. PMID: 25829757.

18. Bae H. Sports for the disabled: history and the classification. Hanyang Med Rev. 2009; 29:94–106.

19. Korea Para Table Tennis Association [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Para Table Tennis Association;c2015. cited 2016 Jul 22. Available from: http://tt.kosad.or.kr/.

20. Korea Disabled Archery Association [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Disabled Archery Association;c2015. cited 2016 Jul 22. Available from: http://archery.kosad.kr/.

21. Curtis KA, Roach KE, Applegate EB, Amar T, Benbow CS, Genecco TD, et al. Reliability and validity of the Wheelchair User's Shoulder Pain Index (WUSPI). Paraplegia. 1995; 33:595–601. PMID: 8848314.

22. Corazza A, Orlandi D, Fabbro E, Ferrero G, Messina C, Sartoris R, et al. Dynamic high-resolution ultrasound of the shoulder: how we do it. Eur J Radiol. 2015; 84:266–277. PMID: 25466650.

23. Rutten MJ, Jager GJ, Blickman JG. From the RSNA refresher courses: US of the rotator cuff: pitfalls, limitations, and artifacts. Radiographics. 2006; 26:589–604. PMID: 16549619.

24. Kerr J, Borbas P, Meyer DC, Gerber C, Buitrago Tellez C, Wieser K. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in the weight-bearing shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015; 24:1894–1899. PMID: 26163283.

25. Shinohara H, Urabe Y, Maeda N, Xie D, Sasadai J, Fujii E. Does shoulder impingement syndrome affect the shoulder kinematics and associated muscle activity in archers? J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2014; 54:772–779. PMID: 25350034.

26. Kim HB, Kim SH, So WY. The relative importance of performance factors in Korean archery. J Strength Cond Res. 2015; 29:1211–1219. PMID: 25226316.

27. Wylie EJ, Chakera TM. Degenerative joint abnormalities in patients with paraplegia of duration greater than 20 years. Paraplegia. 1988; 26:101–106. PMID: 3412779.

28. Fullerton HD, Borckardt JJ, Alfano AP. Shoulder pain: a comparison of wheelchair athletes and nonathletic wheelchair users. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003; 35:1958–1961. PMID: 14652488.

29. Cooper RA, De Luigi AJ. Adaptive sports technology and biomechanics: wheelchairs. PM R. 2014; 6(8 Suppl):S31–S39. PMID: 25134750.

30. Edmonds EW, Dengerink DD. Common conditions in the overhead athlete. Am Fam Physician. 2014; 89:537–541. PMID: 24695599.

Fig. 1

Pattern of shoulder diseases was compared for the dominant side or not, and between the group of wheelchair table-tennis (TT) and archery (AR). The five diseases for the shoulder, in order with counter-clockwise direction, were 'A' subscapularis tendinopathy, 'B' supraspinatus tendinopathy, 'C' infraspinatus tendinopathy, 'D' biceps long head tendinopathy, and 'E' subacromial-subdeltoid bursitis. *p<0.05 by chi-square test, as compared with non-playing arm of TT.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download