Abstract

Thoracic radiculopathy represents an uncommon spinal disorder that is frequently overlooked in the evaluation of thoracic, or abdominal pain syndrome. The clinical representation of this uncommon disorder is often atypical. With many differential diagnoses to consider, it is not surprising that the cause of thoracic radiculopathy is often not discovered for months, or years, after the symptoms arise. We report two rare cases of thoracic radiculopathy; one case was caused by extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma (EES) along the thoracic paraspinal area, and the other by foraminal stenosis, due to a bony spur of the thoracic vertebra. As such, thoracic radiculopathy should be considered in the diagnosis of patients with thoracic and abdominal pain, especially if initial diagnostic studies are inconclusive.

Go to :

Thoracic radiculopathy represents an uncommon spinal disorder that is frequently overlooked in the evaluation of spinal pain syndromes [1]. The symptoms of thoracic radiculopathy, regardless of the cause, are often not recognized, as there is typically no associated motor deficit. When the etiology is disc herniation or trauma, motor deficit or myelopathy may be observed in the advanced stages.

Furthermore, the typical presentation of band-like thoracic or abdominal pain can mimic a myriad of conditions [2]. With many differential diagnoses to consider, it is not surprising that thoracic radiculopathy is often not discovered for months, or years, after symptoms arise [1].

Rarer causes of thoracic radiculopathy described in the literature include post-thoracotomy, paravertebral mesothelial cyst, and myodil cyst [2]. Here, we report two cases of the clinical manifestations, electrodiagnostic findings, and treatments of thoracic radiculopathy due to rare causes.

Go to :

All the information, including the photographs used for the case report, has been provided with the consent of each patient.

A 22-year-old male patient presented with a complaint of stabbing right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain for 1 month. He visited several hospitals and underwent imaging studies (rib series X-ray and abdominopelvic computed tomography [CT]) with no specific results found. He was managed conservatively with analgesic medication and physical therapy, however his symptoms had not resolved and were in fact amplified. He denied any medical and trauma history. There were no gastrointestinal symptoms, weight loss, or other systemic symptoms. The physical examination revealed dysesthesia, hypoesthesia, and pain on the RUQ abdomen to the back at the 8–9th thoracic (T) level (Fig. 1A). The patient's pain was aggravated when in sitting or lying position, and while sleeping at night. Manual muscle testing showed no muscle weakness, and deep tendon reflexes were normal in both lower extremities.

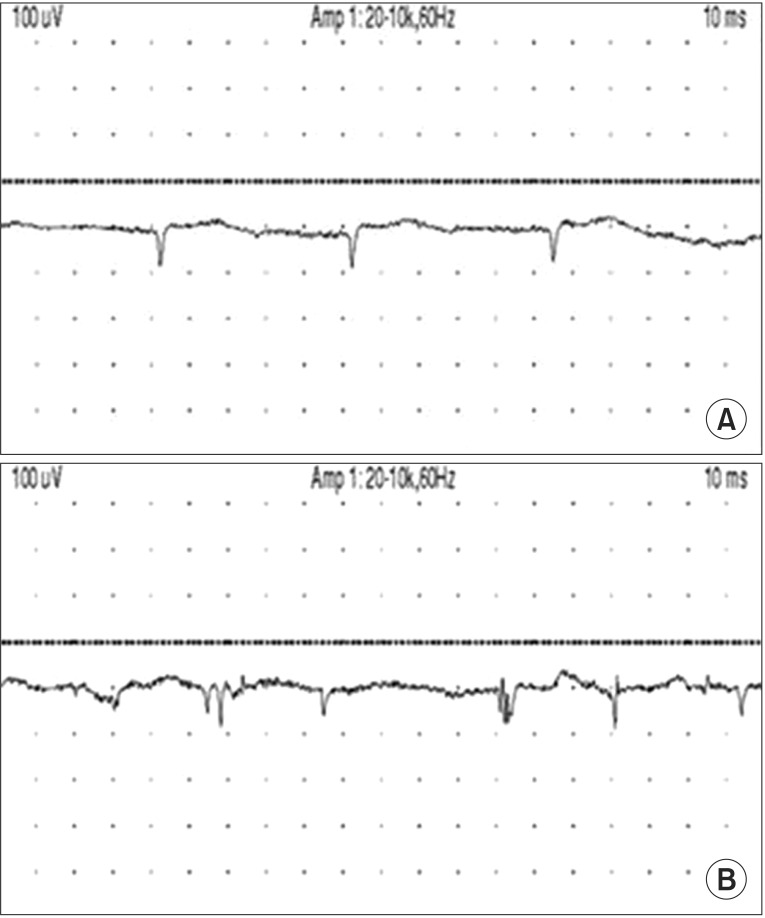

Regarding the nerve conduction study (NCS), the results showed normal responses in all four extremities, and the needle electromyography (EMG) revealed abnormal spontaneous activities (ASA) in the muscles of right paraspinalis at T8-9 level and rectus abdominis (Fig. 2A). Somatosensory evoked potential (SEP) and motor evoked potential (MEP) revealed normal ranged latencies.

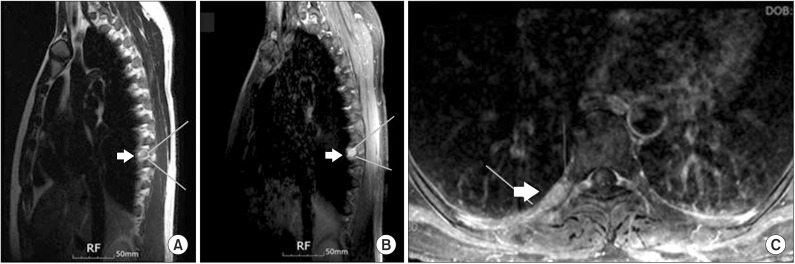

A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic spine was performed, and it revealed a well-enhanced lobulated mass along the right paraspinal area with a suspicious mass extending to the right neural foramen of T8-9 (Fig. 3). CT guided fine-needle aspiration cytology from the paraspinal soft-tissue mass was not possible. Subsequently, we referred the patient to the neurosurgery department for open biopsy and mass excision. During surgery, the result of frozen biopsy was malignant tumor. Therefore, extended mass resection was performed with posterolateral spinal fusion at T8-9. The surgical findings recorded in the operation record that the mass was tangled with the right T8 nerve root from the neural foramen. After surgery, the radicular pain was reduced, however the patient still complained of hypoesthesia on the right T8-9 level. He was referred to the oncology department for chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

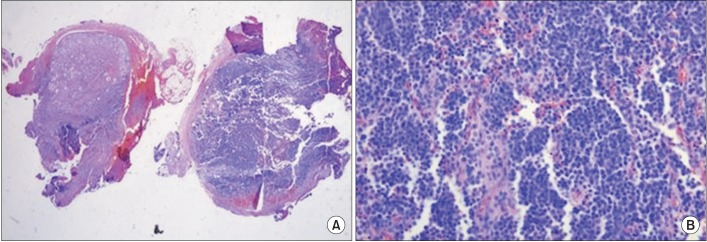

The histopathological report was consistent with Ewing's sarcoma (ES) (Fig. 4). Proliferation of small, round, uniform cells with scant cytoplasm were observed. Immunohistochemically, the tumor cells were positive for a cluster of differentiation 99 (CD99) and neuron-specific enolase. The result of reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) showed that the tumor was positive for EWS-FLI1 fusion transcripts, confirming a chromosomal translocation, t(11;22)(q24;q12). This chromosome abnormality is specific to ES.

A 75-year-old man was referred to our department from the gastroenterology department with a chief complaint of RUQ abdominal pain which had lasted for 2 months. The patient denied any history of trauma, gastrointestinal or pelvic disease, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus (DM).

Before coming to our department, he underwent several diagnostic work-ups, including lumbar spinal MRI, abdominopelvic CT, and blood chemistry tests in several hospitals. However, no specific abnormal findings found were suspected as the cause of the pain. He even underwent surgery to remove a lipoma in his right flank to decrease the pain at another hospital, but following this his flank pain worsened and spread to the RUQ area.

His RUQ pain was aggravated by sitting and standing, but was relieved in the supine position. He denied having any other systemic symptoms. In the physical examination, he felt tenderness in the T8 and T9 spine areas, and complained of a mild sensory deficit with paresthesia at the RUQ abdomen. He also complained of band-like pain in the right T8-9 dermatome (Fig. 1B). In all four extremities, motor and sensory functions were intact, and there was no abnormal upper and lower motor neuron sign.

Three-dimensional CT of the thoracic spine revealed an old compression fracture at the T8-T11 level, and stenosis of the right T8-9 intervertebral foramen with a bony spur encroachment (Fig. 5). The peripheral NCS showed normal responses in all four extremities, but the needle EMG revealed ASA in right paraspinalis muscles at the T8-9 level (Fig. 2B). There was no ASA at any other level of thoracic paraspinal muscles, intercostalis or rectus abdominis muscles. SEP and MEP revealed normal ranged latencies.

With the final diagnosis of thoracic radiculopathy, conservative management such as analgesic medication, including the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, gabapentin, and physical therapy with spinal extension exercise were administered. We performed ultrasound-guided intercostal nerve blocks. The pain was reduced within several weeks. These treatments were maintained for 6 months and provided the patient with pain relief.

Go to :

Extraskeletal Ewing sarcoma (EES) is the extraosseous form of ES. The exact incidence of EES is unknown, however it varies between 10%–13% of the osseous form of ES. The osseous form of ES accounts for 6%–8% of all primary malignant bone tumors [3]. As such, EES is a rare malignant tumor, and it is even rarer to occur in the spinal canal.

The most common sites of EES are the chest wall, paravertebral muscles, extremities, buttocks, and retroperitoneal space [4]. To our knowledge, this is the first report of EES causing radiculopathy without myelopathy. Most other reported cases were spinal epidural EES presenting mainly myelopathy.

Thoracic disc disease and DM represent two of the most frequent etiologies for the development of thoracic radiculopathy [1]. Thoracic disc herniation has no typical characteristics, and no obvious neurological disabilities at first presentation [5]. Symptoms and physical examinations do not provide a definite diagnosis of thoracic radiculopathy [6]. In thoracic disc disease, the age of onset is generally between the third and sixth decades of life. Prognosis for symptomatic relief with nonsurgical management in cases of thoracic disc disease without progressive myelopathy is quite good [1]. However, approximately 80% of patients are diagnosed with ES when they are younger than 20 years old [7]. Generally, ES progresses quite rapidly and its prognosis is poor. The 5-year survival rate of EES specifically has been reported as 38%–67%. The 5-year survival rate in EES around the spinal canal was reported to be 0%–37.5%. A diagnosis of EES tends to be late due to its rarity, as well as the tumor being discovered only after becoming massive [4]. Such a delay in diagnosis of EES, can result in advanced state of malignant tumor and poor prognosis. As such clinicians should consider thoracic radiculopathy in younger patients with unexplained upper quadrant abdominal pain, and be aware that malignant tumors, such as EES, can be the cause of thoracic radiculopathy. Rapid and accurate diagnosis, as well as early surgical resection, affect the treatment outcome of the EES occurring around the spinal canal.

In case 1, the tumors were located in paravertebral spaces and accompanied with extending to right neural foramen of T8-9, thereby mimicking nerve sheath tumors. On MRIs, EES is generally of low to isointense signal, compared with muscle on T1-weighted images, of high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, and exhibits heterogeneous enhancement [8]. In case 1, a neurogenic tumor was suggested by MRI. Schwannoma and neurofibroma are the representative neurogenic tumors which can occur in the spine region. They are most commonly noted between the fourth and sixth decades of life and more slow progressing than ES. Most spinal schwannomas are small, well encapsulated, and do not invade the underlying nerve root. Neurofibroma, by contrast, invade the nerve root, becoming inseparable from it, thereby making complete surgical excision impossible, without damage to the nerve itself [9]. The imaging features cannot definitely distinguish EES from other tumors, such as neurogenic tumors, and so some form of biopsy or partial resection might be needed to confirm the diagnosis, allowing appropriate management.

The electrophysiological evaluation of thoracic radiculopathy is particularly challenging. This is due to the limited techniques available to assist in the diagnosis, as well as the lack of easily accessible muscles representing a myotomal nerve root distribution [10]. The electrodiagnostic evaluation of suspected thoracic radiculopathy should include needle EMG of thoracic paraspinal muscles. Associated intercostals and abdominal musculature may be additional muscles that can help in the diagnosis [1]. Positive sharp waves and fibrillation potentials found in the paraspinal muscles with or without abnormalities in the abdominal, or intercostals muscle, are most suggestive of a thoracic radicular process. The levels of abnormality in the paraspinals can help to localize the T level of the lesion [1].

When we examined the needle EMG of paraspinal muscles, it was slightly difficult to relax the muscles but we investigated multiple levels including those above and below the suspected lesion site. Detection of ASA in the paraspinal muscles at the T8-9 level was distinguishable from those of other levels. It strongly suggests thoracic radiculopathy.

In case 1 only we identified ASA in the rectus abdominis muscle. This result is helpful to diagnose thoracic radiculopathy, combining ASA in the paraspinal muscles. However, the rectus abdominis muscle has a limited representation of levels (T7-12) and extremely poor localization with respect to the level of disease [10]. Moreover, there is potential risk of penetrating the peritoneal cavity or the pleural cavity when performing the EMG of rectus abdominis muscle or intercostal muscle. As such we performed ultrasonography guided EMG to exam these muscles. In spite of the diagnostic challenge of the electrophysiological evaluation of thoracic radiculopathy, it can be helpful to differentiate the causes of thoracic or upper abdominal pain syndromes, and to localize the level of the lesion in thoracic radiculopathy.

We present the first case of ES and the rare case of a bony spur causing thoracic radiculopathy without myelopathy. In conclusion, although quite rare, EES forms an important differential diagnosis in younger patients with a long history of thoracic or upper abdominal pain. If thoracic or upper abdominal pain is accompanied by abnormal neurological examination, electrophysiological evaluation, CT or MRI study of thoracic spine, further evaluations should be considered to find out the causes of pain.

Go to :

References

1. O'Connor RC, Andary MT, Russo RB, DeLano M. Thoracic radiculopathy. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2002; 13:623–644. PMID: 12380552.

2. Mammis A, Bonsignore C, Mogilner AY. Thoracic radiculopathy following spinal cord stimulator placement: case series. Neuromodulation. 2013; 16:443–447. PMID: 23682904.

3. Mukhopadhyay P, Gairola M, Sharma M, Thulkar S, Julka P, Rath G. Primary spinal epidural extraosseous Ewing's sarcoma: report of five cases and literature review. Australas Radiol. 2001; 45:372–379. PMID: 11531770.

4. Yasuda T, Suzuki K, Kanamori M, Hori T, Huang D, Bridge JA, et al. Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma of the thoracic epidural space: case report and review of the literature. Oncol Rep. 2011; 26:711–715. PMID: 21617880.

5. Su JL, Tan WC, Chao CC, Tsai CM, Wu CH. An initial presentation of flank pain caused by thoracic disc herniation. J Emerg Crit Care Med. 2010; 21:221–226.

6. Ozturk C, Tezer M, Sirvanci M, Sarier M, Aydogan M, Hamzaoglu A. Far lateral thoracic disc herniation presenting with flank pain. Spine J. 2006; 6:201–203. PMID: 16517394.

7. Iwamoto Y. Diagnosis and treatment of Ewing's sarcoma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007; 37:79–89. PMID: 17272319.

8. Guyot-Drouot MH, Cotten A, Flipo RM, Lecomte Houcke M, Delcambre B. Contribution of magnetic resonance imaging to the diagnosis of extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. 1999; 66:516–519. PMID: 10567983.

9. Rustagi T, Badve S, Parekh AN. Sciatica from a foraminal lumbar root schwannoma: case report and review of literature. Case Rep Orthop. 2012; 2012:142143. PMID: 23259107.

10. Dumitru D, Zwarts MJ. Lumbosacral plexopathies and proximal mononeuropathies. In : Dumitru D, Amato AA, Zwarts MJ, editors. Electrodiagnostic medicine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Hanley & Belfus;2002. p. 750–751.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download