This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Osteomyelitis is a bone infection caused by bacteria or other germs. Gram-positive cocci are the most common etiological organisms of calcaneal osteomyelitis; whereas, non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are rarely documented. We reported a case of NTM calcaneal osteomyelitis in a 51-year-old female patient. She had been previously treated in many local clinics with multiple local steroid injection over 50 times and extracorporeal shock-wave therapy over 20 times with the impression of plantar fasciitis for 3 years prior. Diagnostic workup revealed a calcaneal osteomyelitis and polymerase chain reaction assay on bone aspirate specimens confirmed the diagnosis of non-tuberculous mycobacterial osteomyelitis. The patient had a partial calcanectomy with antitubercular therapy. Six months after surgery, a follow-up magnetic resonance imaging showed localized chronic osteomyelitis with abscess formation. We continued anti-tubercular therapy without operation. At 18-month follow-up after surgery and comprehensive rehabilitation therapy, she was ambulating normally and able to carry out her daily activities without any discomfort.

Go to :

Keywords: Osteomyelitis, Nontuberculous mycobacteria, Plantar fasciitis

INTRODUCTION

Calcaneal osteomyelitis requires careful planning and thorough evaluation. The calcaneus is a shock absorbing structure, often with poor tissue coverage to close the wound and poor vascularity of the skin envelope anatomically is. Calcaneal osteomyelitis is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are an unusual cause of skeletal infection in immunocompetent patients.

We reported a patient who developed calcaneal osteomyelitis by a NTM following multiple steroid injection for plantar fasciitis.

Go to :

CASE REPORT

A 51-year-old female visited our clinics due to bilateral plantar heel pain of visual analogue scale (VAS) 10 and limping gait, which was worse with activity and/or upon arising in the morning. She had no previous medical history including feet infection, pedal ulcerations and peripheral vascular disease except plantar fasciitis. She had been previously treated in many local clinics with steroid injection over 50 times and extracorporeal shock-wave therapy over 20 times with the impression of plantar fasciitis for 3 years prior. On physical examination, she had no systemic symptoms and no cushingoid appearance. She experienced a sensation of mild heat, swelling and tenderness of right medial calcaneal tuberosity (

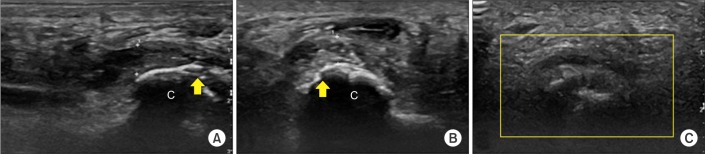

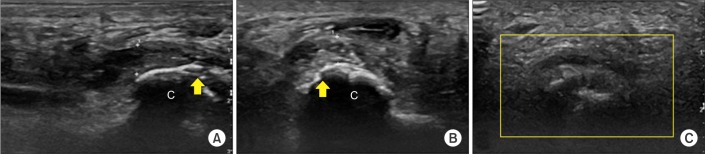

Fig. 1A) with localized tenderness in the bilateral medial plantar heel area. The calcaneal squeezing test was positive in right calcaneus. Ultrasonography showed thickened plantar fascia of both feet and hypoechoic lesions with fat pad atrophy. The plantar aspect of right calcaneus showed cortical irregularity and hypoechoic swelling with edematous change in the surrounding soft tissues (

Fig. 2A,

B). Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed cortical destruction at the right medial calcaneal tuberosity, which presented as diffuse osteomyelitis (

Fig. 1B,

C). Laboratory examination showed a white blood cell count of 6,800/mm

3 (69.2% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, 20.9% lymphocytes, and 6.6% monocytes), an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 20 mm/hr, and C-reactive protein level of 0.33 mg/L. The blood cultures showed no growth and administration of broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics was initiated. Subsequently, she was referred to the department of orthopedic surgery and required partial calcanectomy. The operation site was packed with geneX bone graft substitute (calcium sulfate absorbable beads impregnated with vancomycin and tobramycin) that was removed 14 days after implantation (

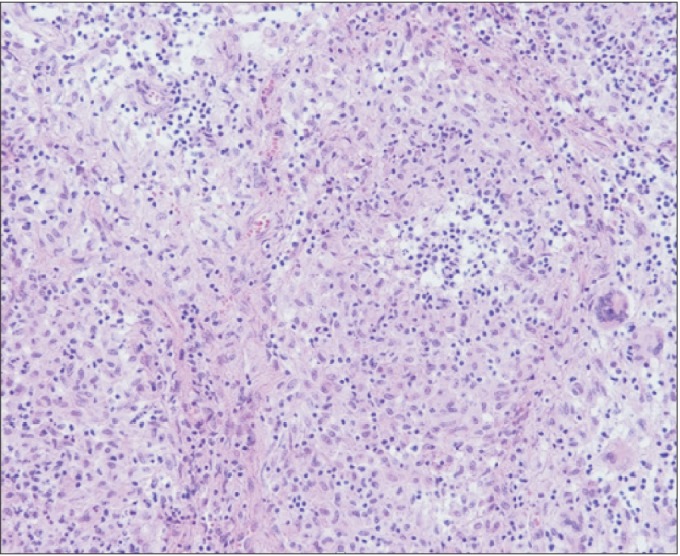

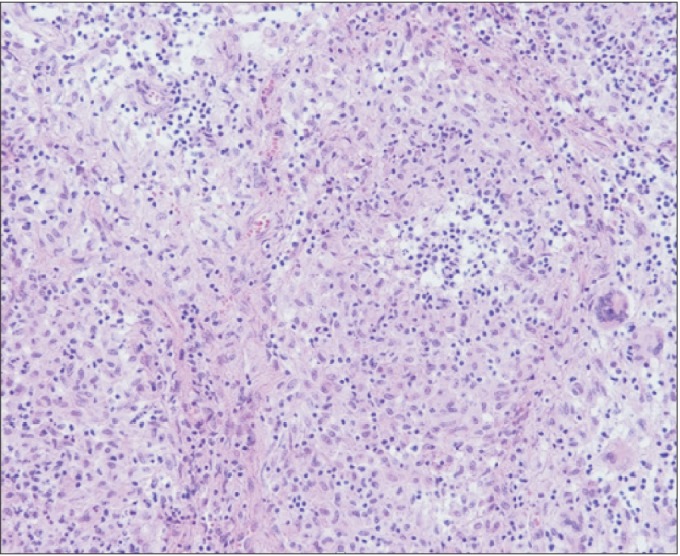

Fig. 1D). Culture of intra-operative bone specimen showed no bacterial growth. Histology showed granulomatous inflammation with multinucleated giant cells (

Fig. 3). Microbiological tissue cultures including pyogenic bacteria and acid-fast bacilli remained negative. Analyses of DNA extracted from tissue specimens were positive for NTM on polymerase chain reaction. However, the chest computed tomography, abdominal-pelvic computed tomography, and endoscopic biopsy were negative for primary tuberculosis. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), cellular and humoral immunity showed no evidence of immunodeficiency. Sequence analyses of the interferon-γ receptor (IFNGR) gene indicated no mutation of the INF receptor. The patient was started on 5-drugs (cefoxitin, amikacin, azithromycin, INH, rifampicin) for 1 month followed by azithromycin for the next 11 months. Her gait gradually advanced from toe-touch weight-bearing to weight-bearing as tolerated.

| Fig. 1(A) Mild swelling and color change over the right calcaneus. (B) Sagittal and (C) axial fat-suppressed T2-weighted magnetic resonance scan demonstrates cortical destruction at right medial calcaneal tuberosity with surrounding soft tissue inflammation and swelling over plantar aspect. (D) The operation site was packed with geneX bone graft substitute.

|

| Fig. 2(A) Longitudinal scan of right plantar heel. The plantar fascia was grossly thickened and measured 5.6 mm (distance between crosses) at the anteroinferior border of the calcaneus, 'c'. (B) Transverse scan of right plantar heel. Plantar aspect of right calcaneus showed cortical irregularity (yellow arrows) and hypoechoic swelling with edematous change in the surrounding soft tissues. (C) Color Doppler ultrasonography showed no vascularity in the right calcaneus.

|

| Fig. 3Low power (200×) hematoxylin and eosin stained specimen showed diffuse ill-defined granulomatous inflammation with Langerhans giant cells that is highly suggestive of a mycobacterial infection.

|

Six months after surgery, a follow-up MRI showed relative well-marginated osteolytic lesion with thick peripheral rim enhancement of right calcaneus posterior portion, which is suggestive of chronic osteomyelitis with abscess formation (

Fig. 4). In consultation with the departments of osteosurgery and infectious diseases, we decided to continue antimicrobial therapy without further surgical intervention, since infection sign was not observed and her plantar heel pain was improved (VAS reductions >80%). In addition, she received comprehensive management including lifestyle modification, and heel cushion for treatment of plantar fasciitis.

| Fig. 4(A) Sagittal and (B) axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance scan of right foot. The image showed relative well-marginated osteolytic lesion with loculated fluid collection and adjacent thick peripheral rim enhancement of right calcaneus posterior portion, which is demonstrated as localized chronic stage osteomyelitis with abscess formation.

|

At the 18-month follow-up, the patient had no pain and the radiograph showed remineralization of bones with sclerosis of joint margins (

Fig. 5). She could ambulate normally in regular shoes with full restoration of symptoms. Furthermore, after comprehensive rehabilitation therapy, she could carry out her daily activities without any discomfort.

| Fig. 5(A) Lateral view of the foot showed predominantly lytic lesion involving the calcaneus. (B) At the 18-month follow-up, radiograph showed remineralization of bones with sclerosis of calcaneus.

|

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Plantar fasciitis is a common cause of heel pain in adults. Plantar fasciitis is generally regarded as a self-limited condition, with >80% of cases resolving within 12 months, regardless of therapy [

1]. However, for prolonged intractable plantar heel pain, as in our case, several causes such as heel pad atrophy, tendinopathy, nerve entrapment, calcaneal stress fractures, tumor, plantar fascial tear and calcaneal osteomyelitis should be considered [

2].

In this case, the patient with intractable chronic plantar heel pain with prior treatment of multiple steroid injection was diagnosed as NTM calcaneal osteomyelitis based on MRI and histologic findings. To our knowledge, this is the first such case to be reported in the literature.

Osteomyelitis involves the calcaneus in 7%–8% of cases and is typically associated with recent trauma, diabetic ulcers, open fractures, or puncture wounds. The most common etiological organism of calcaneal osteomyelitis are gram-positive cocci of which

Staphylococcus aureus,

Staphylococcus epidermidis, and

Streptococcus spp. account for 73% cases; whereas, NTM are rarely documented [

2]. To the best of our knowledge, only 2 previous cases are reported in the biomedical literature. Elsayed and Read [

3] reported a

M. haemophilum osteomyelitis in an adult woman with polycythemia vera, and Michelarakis and Varouhaki [

4] reported an atypical mycobacterial osteomyelitis with interferon-γ receptor deficiency (IFN-γ). NTM causes chronic granulomatous infections involving tendons, bursae, bones and joints, as a complication of penetrating trauma or immunodeficiency, which is associated with a genetic defect of the IFN-γ receptor [

5]. In our patient, no primary or acquired immunodeficiency including mutation of

IFNR gene was found.

Osteomyelitis is classified into 2 primary categories based on the different routes of infection: hematogenous osteomyelitis and direct or contiguous inoculation osteomyelitis.

Hematogenous osteomyelitis is most commonly seen in metaphyses of long bones of children or immunosuppressed patients. Bone infections with NTM occasionally arise via hematogenous seeding from a distant site, such as the lung. In this case, the chest computed tomography, abdominal-pelvic computed tomography, and endoscopic biopsy were negative for primary tuberculosis. Also, the patient had no signs of systemic inflammation and cellular or humoral immune dysfunction. However, she had received multiple local corticosteroid injections that may have produced local as well as systemic immunosuppression and alterations of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis; moreover, it may have been a risk factor of atypical mycobacterial bone infection. However, there was no definite evidence of Cushing syndrome or immunosuppressed status.

Direct or contiguous inoculation osteomyelitis is caused by contact of the tissue and bacteria or continuous spread from an adjacent source. Steroid injections are a popular method for treating plantar fasciitis. Generally, corticosteroid injections are given in a series of 3, spaced a few weeks apart [

6]. In this case, patient was treated with steroid injection over 50 times for the last 3 years. Indiscriminate steroid use is undesirable, because local steroid injections can induce fat necrosis and tendon or fascia ruptures due to necrosis of collagenous tissue.

Complications of infections following skin punctures under aseptic techniques are another suggested hypothesis. It can cause rare but serious problems such as osteomyelitis. Only 2 reports in the current literature describe calcaneal osteomyelitis as a complication of such injection, but do not identify the organism of calcaneal osteomyelitis [

78].

In this case, the patients' complaint included a sensation of heat, swelling and tenderness of right posterior heel as well as medial plantar heel area. Calcaneal squeezing test was positive and other clinical features were not consistent with plantar fasciitis. We were suspicious of calcaneal pathology and the final diagnosis was NTM calcaneal osteomyelitis. At present, there is no consensus on guidelines for treatment of skeletal infections caused by NTM. In this case, after prolonged anti-tuberculous therapy in combination with surgical debridement, the patient could walk independently without discomfort. Accordingly, an accurate differential diagnosis with careful history and physical examination and proper treatment by guideline [

26] were necessary.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download