Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of post-stroke depression (PSD) on rehabilitation outcome and to investigate the risk factors of PSD, especially, the role of caregivers type (family or professional) in subacute stroke patients.

Methods

Two hundred twenty-six stroke patients were enrolled retrospectively. All the subjects' basic characteristics, Korean version of the Beck Depression Inventory (K-BDI), Korean version of the Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI), and the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) were recorded when the patient was transferred into the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine and at the time of discharge. The results were statistically analyzed by using SPSS ver. 20.0.

Results

The patients' K-BDI score showed a significantly negative association with K-MBI at discharge (β=-0.473, p<0.001) and a significantly positive association with the mRS score at discharge (β=0.316, p<0.001). Patients with lesions on the left hemisphere (odds ratio [OR], 3.882; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.726-8.733) and professional caregiver support (OR, 0.028; 95% CI, 0.012-0.065) had a higher rate of depression.

Conclusion

Depression was prevalent in stroke patients, and it had a negative effect on patients' functional outcome. Patients who had a lesion on the right hemisphere had less depression. The type of caregiver was related to the incidence of subacute PSD, and family caregivers were found to lower the frequency of stroke patients' depression.

Every year, about 16 million people in the world have their first strokes [1], and stroke is the second leading cause of death in Korea [2]. Stroke survivors have an increased incidence of neuropsychiatric disorders, such as generalized anxiety disorders, psychotic states, secondary mania, apathy, obsessive disorders, and depression [3]. Among these, depression is one of the most common neuropsychiatric disturbances in first few months following a stroke, occurring in 20%-65% of stroke patients [4,5]. It is so-called post-stroke depression (PSD). PSD has been negatively associated with survival, cost of medical care, and compliance with therapy including rehabilitation, functional outcome, resumption of social activities, and quality of life [6].

Studies have been conducted to better describe the relationship between stroke and depression. Kauhanen et al. [7] reported that PSD is related to dependence with respect to activities of daily living, and to the severity of neurological deficits. Whyte and Mulsant [8] suggested a possible biological relationship between depression and structural brain injury caused by a stroke. In addition, Anderson et al. [9] proposed that cerebrovascular risk factors increase the risk of depression.

Care is an important issue for stroke patients suffering from neurological deficits. Particularly among acute and subacute stroke patients, those with moderate to severe impairment have to depend on others to accomplish most of their activities of daily living and such roles are csarried out by their main caregivers [2]. Such care has usually been performed by the family, but care by professional caregivers is now being widely used in response to the structural change of Korean society resulting from the increasing life expectancy and elderly population [10,11]. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the type of caregiver (family or professional caregiver) and their effect in stroke patients' depression.

Although the relationship between stroke and depression is described extensively in literature worldwide, there are limited studies in Korea pertaining to the risk factors of PSD in patients at a subacute stage of stroke and regarding the effect of PSD on rehabilitation outcome. The aims of this study are to evaluate the effect of PSD on rehabilitation outcome and to investigate the risk factors of PSD, especially, the role of caregiver type (family or professional) as a risk factor for stroke patients' subacute PSD.

Data from stroke patients who were transferred into the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of Konyang University Hospital from January 2011 to December 2013 were retrospectively recruited from the patients' medical records. Before being transferred in, the patients were treated in the Department of Neurology or Neurosurgery of our hospital. The patients' average duration from the onset of stroke was 11.93±2.43 days.

Inclusion criteria were (1) patients over 18 years of age who underwent their first stroke; (2) confirmed diagnosis of stroke by medical records, imaging study, and clinical examination; and (3) patients who had never suffered from psychiatric disorders before the stroke. Exclusion criteria included the following: (1) transient ischemic attack, subdural hematoma, or subarachnoid hemorrhage; (2) history of any central nervous system disease other than stroke; (3) severe cognitive impairment as defined by the Korean version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE-K) score of <19 [12]; (4) severe auditory or visual impairment; and (5) recurrent stroke before assessment.

Depression was measured by using the Korean version of the Beck Depression Inventory (K-BDI), which is commonly used to evaluate depression. It consists of 21 questions (scoring up to 63 points) and a score higher than 10 is considered to represent depressive symptoms [13]. The K-BDI was measured 3 to 4 weeks (24±2.32 days) after the transfer, and the survey was conducted by a clinical psychologist in our hospital. To find the correlation between depression and factors, the patients were divided into two groups by a cutoff score of 10 [14].

The functional outcomes of stroke patients were measured using the Korean versions of the Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI) [15] and the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) [16] upon transfer into the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine of Konyang University Hospital and at the time of discharge.

The K-MBI is a Korean translation of the 5th version of MBI, translated by Jung et al. [15]. It consists of 10 items, and its score ranges from 0 to 100, with a high score meaning that the stroke patient functions well. It is considered to be a reliable and valid instrument for evaluating the functional status of subjects with stroke.

The mRS is a tool that has a score range from 0 to 6, with a high score representing a poor functional outcome. This tool is efficient in assessing stroke patients' functions [16].

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 20.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, USA). The baseline demographic characteristics of stroke patients were analyzed. A multiple linear regression model was used to examine the association between depression and functional outcome. In order to find the association of various factors with depression, Pearson correlation test, Pearson chi-square test, and a linear logistic regression model were used. Statistical significance was assigned at p-values less than 0.05.

A total of 226 patients were recruited in the study. The mean age of the patients was 68.45±13.00 years and the mean BDI score was 23.04±17.35 points. The patients' functional outcomes were all improved at discharge. Other demographic and general characteristics of the patients are listed in Table 1.

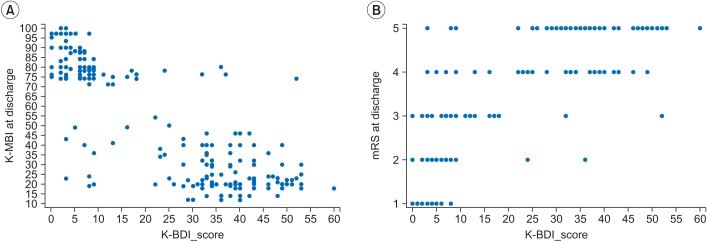

The association between the initial factors and functional outcomes are listed in Table 2. The BDI score of stroke patients showed a significantly negative association with the K-MBI at discharge (β=-0.473, p<0.001) and a significantly positive association with the mRS score at discharge (β=0.316, p<0.001). Fig. 1A and B are scatter plots showing the relationship between the K-BDI and functional outcomes (K-MBI, mRS) at discharge.

Using a cutoff value of the BDI score, the stroke patients were divided into two groups. Those with a BDI score <10 were the non-depressed group, and those with a BDI≥10, the depressed group. Table 3 contains the association between various factors and depression. A lesion on the left hemisphere, smoking history, and support by a professional caregiver showed a significant association with stroke patients' depression (p<0.05). There was no significant association between the other factors we examined and depression.

Table 4 shows the result of linear logistic regression analysis of factors that influence the depression of stroke patients. Patients with a lesion on the left hemisphere (odds ratio [OR], 3.882; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.726-8.733) and professional caregiver support (OR, 0.028; 95% CI, 0.012-0.065) had higher rates of depression.

In this study, more than half of the patients had depressive symptoms. This prevalence rate agrees with the study of Farner et al. [17], which reported 56% prevalence rate of PSD. We found that PSD patients had poor functional outcomes at discharge. This finding corresponds with that of Schmid et al. [18]. They investigated 174 patients with PSD over 12 weeks and found that the severity of depression symptoms was negatively associated with the patients' functional independence. As one of the main goals of stroke rehabilitation is restoring the patients' functional outcomes, this finding reinforces the importance of treatment for PSD in stroke rehabilitation.

Also, we investigated several factors of depression. We found patients who had a lesion on their right hemispheres had lower rates of depression. The type of caregiver had a significant effect on the incidence of subacute PSD, and patients supported by a family caregiver showed a lower frequency of depression. However, sex, past history of certain conditions (hypertension, smoking, dyslipidemia, marital status, and educational duration), and type of stroke were not associated with subacute PSD.

The risk factors of PSD in the present study are comparable to those found in other studies. In our study, age was not associated with PSD. This finding is consistent with that of Brown et al. [19] and Fuentes et al. [20]. They found no association between depression and age. According to the study of Berg et al. [21], however, age was the most significant determinant of depression and older patients were more depressed after suffering acute strokes. This difference might be because the patients recruited in our study were older (68.45±13.00 years) than those in other studies, and therefore the effect of age was muted. As shown in our study, a large number of patients had their first stroke at an advanced age. For elderly patients, therefore, age may not be a determinant of depression.

In our study, sex was not associated with PSD. Kotila et al. [22] reported that the female sex is associated with depression. However, Berg et al. [23] reported that, in a chronic phase, men seemed to be more depressed than women. According to the study of Berg et al. [23], the nature of PSD may be different between the two sexes and men are more concerned about working disability and have a poorer coping ability than women. The discrepancy between our study and others is likely due to the period of investigation. Patients recruited in our study were investigated within 3 months of having their strokes.

In this study, cognitive function measured by the MMSE-K was not related to PSD. Some studies evaluated the relationship between decreased cognitive function and depression. In our study, however, cognitively impaired patients with a low MMSE-K score and aphasia patients were excluded by criteria, and this confounded the effect of cognitive function as a risk factor of depression [12].

Furthermore, our study found that a lesion on the left hemisphere was associated with depression. Our finding is consistent with the study of Paradiso and Robinson [24] which suggested that depression was associated with lesions on the left hemisphere as well. However, some studies found no association between stroke lesions and depression [12,19]. The significance of our result is proposed by the concept of anosognosic disturbance. Stroke patients who are able to realize their disabilities respond to depressive symptoms soon after stroke, but this normal reaction is lacking in patients who suffer anosognosic disturbances. Because anosognosic disturbances are known to occur in right hemisphere lesions in an acute phase, the prevalence of depressive disorders may be higher after a left hemisphere stroke [21]. Furthermore, Bhogal et al. [25] reviewed the relevant literature and proposed that when inpatient population studies were compared with community-based studies, PSD of left hemisphere lesion stroke patients was more frequent in the inpatient population. As the subjects in our study were an inpatient population, this might influence the result. However, the association between the site of the stroke lesion and the likelihood of the development of depression remains controversial [21,25].

This study is significant in that, to the best of the author's knowledge, it is the first study to investigate the type of caregiver as a risk factor of PSD. Previous studies have focused on caregivers' depression and suggested that caregivers can easily be depressed by their burdens. They emphasized that it would be important to identify depressed caregivers [26,27]. Approaching this situation from a different viewpoint, however, this study found that patients supported by a family caregiver showed remarkably fewer depression symptoms. Furthermore, such patients showed good functional outcomes. Previous studies compared the course of the illness at day hospitals and outpatient services with that at home care, and found great advantages in the latter [28,29]. These findings suggest that family members play important roles by offering emotional encouragement and helping compliance with therapeutic instructions because most of patients are mostly dependent, disabled, or both [30]. Also, Tsouna-Hadjis et al. [31] investigated 43 first-stroke patients and reported that high-level family support is associated with an improvement of depression and functional outcomes in acute-stage stroke patients. Therefore, even though the number of professional caregivers is increasing in Korea [11], family caregivers can give physical and psychological support that is more desirable and effective from the stroke survivors' points of view.

There are several limitations in this study. First, the retrospective nature of the study may influence the results. Second, the K-BDI was the only tool to investigate depression. However, the K-BDI is used widely and its reliability and validity for screening PSD have been wellestablished [32]. Third, we did not examine other risk factors of PSD, such as the severity of stroke and the type of PSD symptoms. Fourth, the period of investigation was short and the number of subjects enrolled was small, limiting its applicability to a more general population. The last limitation is that stroke patients were divided dichotomously into the depressive and non-depressive groups. Further research is required for these limitations.

In conclusion, depression was prevalent in stroke patients, and it has a negative effect on patients' functional outcome. Because the patients' functional status improves rapidly in the early period of rehabilitation, it is necessary to focus on the treatment of depression. Also, family caregivers' support can improve the patients' depression and it can be a modifiable factor. Therefore, the rehabilitation team should take into account it and reflect this fact in planning a treatment schedule.

However, various factors discussed in this study are still controversial. Although many studies have evaluated the risk factors of PSD, debates still remain. Thus, longitudinal prospective research is required in the future, complete with a longer period and a larger number of subjects.

References

1. European Stroke Initiative Executive Committee. EUSI Writing Committee. European Stroke Initiative Recommendations for Stroke Management-update 2003. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003; 16:311–337. PMID: 14584488.

2. Yoo EK, Jeon S, Yang JE. The effects of a support group intervention on the burden of primary family caregivers of stroke patients. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2007; 37:693–702.

3. Angelelli P, Paolucci S, Bivona U, Piccardi L, Ciurli P, Cantagallo A, et al. Development of neuropsychiatric symptoms in poststroke patients: a cross-sectional study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004; 110:55–63. PMID: 15180780.

4. Primeau F. Post-stroke depression: a critical review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 1988; 33:757–765. PMID: 3060238.

5. Hackett ML, Yapa C, Parag V, Anderson CS. Frequency of depression after stroke: a systematic review of observational studies. Stroke. 2005; 36:1330–1340. PMID: 15879342.

6. Gaete JM, Bogousslavsky J. Post-stroke depression. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008; 8:75–92. PMID: 18088202.

7. Kauhanen M, Korpelainen JT, Hiltunen P, Brusin E, Mononen H, Maatta R, et al. Poststroke depression correlates with cognitive impairment and neurological deficits. Stroke. 1999; 30:1875–1880. PMID: 10471439.

8. Whyte EM, Mulsant BH. Post stroke depression: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and biological treatment. Biol Psychiatry. 2002; 52:253–264. PMID: 12182931.

9. Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001; 24:1069–1078. PMID: 11375373.

10. Kwon S, Tae YS. The experience of adult Korean children caring for parents institutionalized with dementia. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2014; 44:41–54. PMID: 24637285.

11. Lee HS. Caregiver burden in caring for elders before and after long-term care service in Korea. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2012; 42:236–247. PMID: 22699173.

12. Tang WK, Chan SS, Chiu HF, Ungvari GS, Wong KS, Kwok TC, et al. Poststroke depression in Chinese patients: frequency, psychosocial, clinical, and radiological determinants. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005; 18:45–51. PMID: 15681628.

13. Lee MK, Lee YH, Park SH, Sohn CH, Jung YJ, Hong SK, et al. A standardization study of Beck Depression Inventory (I): Korean version (K-BDI): reliability land factor analysis. Korean J Psychopathol. 1995; 4:77–95.

14. Shin JC, Goo HR, Yu SJ, Kim DH, Yoon SY. Depression and quality of life in patients within the first 6 months after the spinal cord injury. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012; 36:119–125. PMID: 22506244.

15. Jung HY, Park BK, Shin HS, Kang YK, Pyun SB, Paik NJ, et al. Development of the Korean version of Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI): multi-center study for subjects with stroke. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2007; 31:283–297.

16. van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Visser MC, Schouten HJ, van Gijn J. Interobserver agreement for the assessment of handicap in stroke patients. Stroke. 1988; 19:604–607. PMID: 3363593.

17. Farner L, Wagle J, Engedal K, Flekkoy KM, Wyller TB, Fure B. Depressive symptoms in stroke patients: a 13 month follow-up study of patients referred to a rehabilitation unit. J Affect Disord. 2010; 127:211–218. PMID: 20933286.

18. Schmid AA, Kroenke K, Hendrie HC, Bakas T, Sutherland JM, Williams LS. Poststroke depression and treatment effects on functional outcomes. Neurology. 2011; 76:1000–1005. PMID: 21403112.

19. Brown C, Hasson H, Thyselius V, Almborg AH. Poststroke depression and functional independence: a conundrum. Acta Neurol Scand. 2012; 126:45–51. PMID: 21992112.

20. Fuentes B, Ortiz X, Sanjose B, Frank A, Diez-Tejedor E. Post-stroke depression: can we predict its development from the acute stroke phase? Acta Neurol Scand. 2009; 120:150–156. PMID: 19154533.

21. Berg A, Palomaki H, Lehtihalmes M, Lonnqvist J, Kaste M. Poststroke depression in acute phase after stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001; 12:14–20. PMID: 11435674.

22. Kotila M, Numminen H, Waltimo O, Kaste M. Depression after stroke: results of the FINNSTROKE Study. Stroke. 1998; 29:368–372. PMID: 9472876.

23. Berg A, Palomaki H, Lehtihalmes M, Lonnqvist J, Kaste M. Poststroke depression: an 18-month follow-up. Stroke. 2003; 34:138–143. PMID: 12511765.

24. Paradiso S, Robinson RG. Minor depression after stroke: an initial validation of the DSM-IV construct. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999; 7:244–251. PMID: 10438696.

25. Bhogal SK, Teasell R, Foley N, Speechley M. Lesion location and poststroke depression: systematic review of the methodological limitations in the literature. Stroke. 2004; 35:794–802. PMID: 14963278.

26. Epstein-Lubow GP, Beevers CG, Bishop DS, Miller IW. Family functioning is associated with depressive symptoms in caregivers of acute stroke survivors. ArchPhys Med Rehabil. 2009; 90:947–955.

27. Tang WK, Lau CG, Mok V, Ungvari GS, Wong KS. Burden of Chinese stroke family caregivers: the Hong Kong experience. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011; 92:1462–1467. PMID: 21878218.

28. Young JB, Forster A. The Bradford community stroke trial: results at six months. BMJ. 1992; 304:1085–1089. PMID: 1586821.

29. Johansson BB, Jadback G, Norrving B, Widner H, Wiklund I. Evaluation of long-term functional status in first-ever stroke patients in a defined population. Scand J Rehabil Med Suppl. 1992; 26:105–114. PMID: 1488633.

30. Reiss D, Gonzalez S, Kramer N. Family process, chronic illness, and death: on the weakness of strong bonds. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986; 43:795–804. PMID: 3729675.

31. Tsouna-Hadjis E, Vemmos KN, Zakopoulos N, Stamatelopoulos S. First-stroke recovery process: the role of family social support. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000; 81:881–887. PMID: 10895999.

32. Kang HJ, Stewart R, Kim JM, Jang JE, Kim SY, Bae KY, et al. Comparative validity of depression assessment scales for screening poststroke depression. J Affect Disord. 2013; 147:186–191. PMID: 23167974.

Fig. 1

(A) Scatter plot showing the relationship between Korean version of Beck Depression Inventory (K-BDI) and Korean version of Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI). (B) Scatter plot showing the relation between K-BDI and modified Rankin Scale (mRS).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download