Abstract

Objective

To apply tailored rehabilitation education to video display terminal (VDT) workers with musculoskeletal pain and to assess changes in musculoskeletal pain after rehabilitation education.

Methods

A total of 8,828 VDT workers were screened for musculoskeletal disorders using a self-report questionnaire. Six hundred twenty-six VDT workers selected based on their questionnaires were enrolled in musculoskeletal rehabilitation education, which consisted of education on VDT syndrome and confirmed diseases, exercise therapy including self-stretching and strengthening, and posture correction. One year later, a follow-up screening survey was performed on 316 VDT workers, and the results were compared with the previous data.

Results

Compared with the initial survey, pain intensity was significantly decreased in the neck area; pain duration and frequency were significantly decreased in the low back area; and pain duration, intensity, and frequency were significantly decreased in the shoulder and wrist after tailored rehabilitation education. In addition, pain duration, intensity, and frequency showed a greater significant decrease after tailored rehabilitation education in the mild pain group than in the severe pain group.

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders have become a major problem in users of video display terminals (VDT) as VDT use has increased because of increased office automation [1234].

According to the World Health Organization, a work-related musculoskeletal disorder is defined as a disorder of the muscle, tendon, peripheral nerve, and vascular system that is generated, preceded, or aggravated by repeated or continuous use of the body [5]. This definition focuses on repeated use and its causative role in occurrence of disease. The National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) defined a work-related musculoskeletal disorder as pain, spasticity, and burning or tingling sensations in the neck, shoulder, elbow, forearm, wrist, or hand that last for longer than one week or appear at least once a month for one year [5].

In Korea, studies about work-related musculoskeletal disorders in VDT workers have mostly addressed the prevalence and risk factors of symptoms of the neck and upper extremities. These studies have mainly been conducted in the fields of occupational and environmental medicine and have mostly concerned the diagnosis and prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders [135].

Currently, education on muscle-relaxing exercises and regular joint and muscle-strengthening exercises is usually assigned in order to prevent musculoskeletal disorders in worker who perform repetitive upper extremity tasks such as VDT use. In the case of mild pain, physical and exercise therapy have been widely recommended [67]. However, in recent studies, exercise and ergonomics did not significantly reduce musculoskeletal disorder symptoms [8910]. In spite of this controversy, there have been few instances in which rehabilitation education has been tailored to the individual characteristics of musculoskeletal disorders based on accurate diagnosis. Accordingly, there have also been few reports about the effects of rehabilitation education or symptom change after rehabilitation education.

Therefore, in this study, we conducted a survey to analyze changes in and characteristics of musculoskeletal symptoms after tailored rehabilitation education among VDT workers with work-related musculoskeletal disorders.

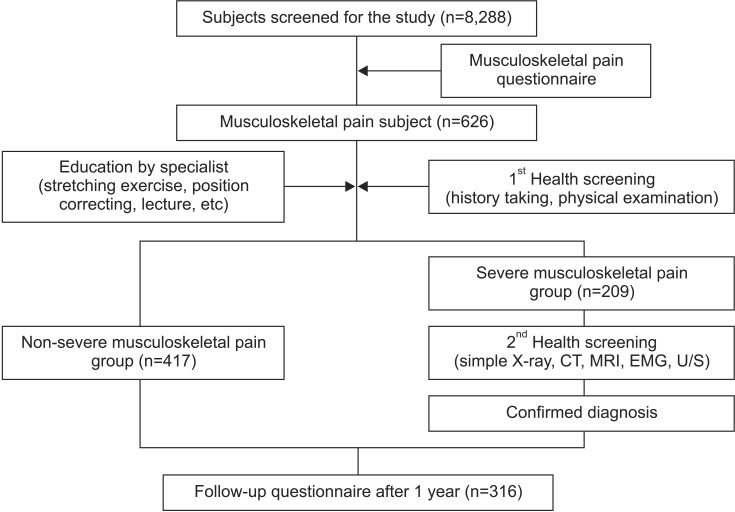

We administered a questionnaire survey to 8,828 VDT workers who were employed as general office workers. We conducted tailored rehabilitation education consisting of explaining the characteristics of musculoskeletal disorders, exercise education, posture correction education, and improving the working environments of 626 subjects with musculoskeletal symptoms. One year later, we followed up with 316 subjects and conducted the same questionnaire survey (Fig. 1).

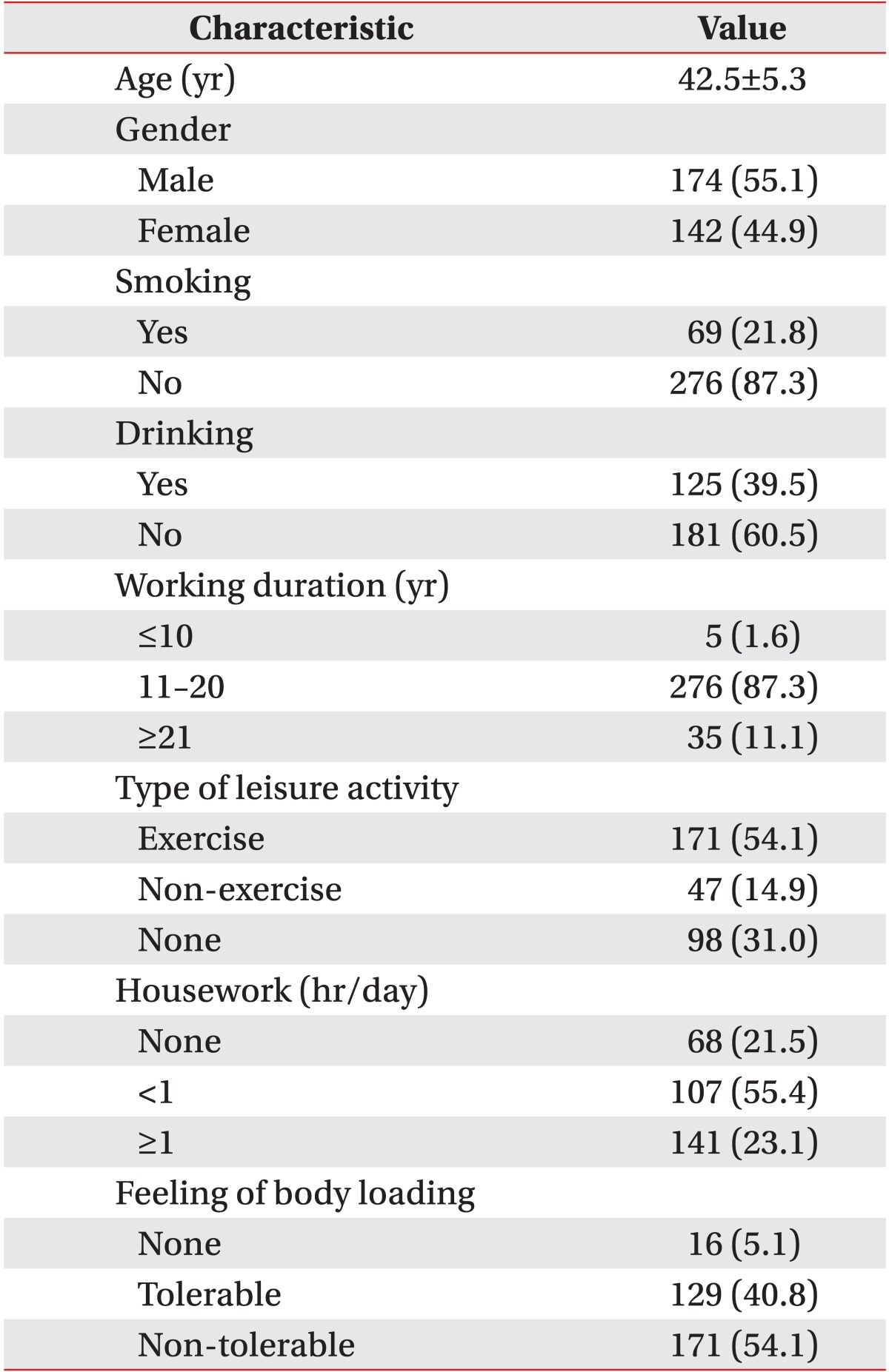

The questionnaire in the present study consisted of two parts. The first part focused on general characteristics, working conditions, and musculoskeletal symptoms and assessed demographic information on age, gender, years of service, history of alcohol consumption and smoking, hobbies, house work, and physical burden of working. History of alcohol consumption and smoking history were categorized as yes or no. Years of service were categorized as less than 10 years, more than 10 years but less than 20 years, and more than 20 years. Hobby was categorized as exercise, non-exercise or none and housework as less than one hour, more than one hour, or none; and physical burden of working as tolerable or non-tolerable.

The second part of the questionnaire concerned musculoskeletal symptoms and was adapted from the Musculoskeletal Symptom Questionnaire in the Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency guidelines on surveys of risk factors related to work-related musculoskeletal pain. Pain regions were categorized as neck, shoulder, elbow, wrist, low back, and lower extremities [11]. Subjective symptoms were defined as moderate or higher level of symptoms (pain, throbbing, stiffness, burning sensation, insensibility or tingling sensation) that lasted for more than one week or occurred at least once a month during the past year, following NIOSH standards [12]. We classified pain intensity as mild, moderate, or severe [13]; duration as less than one day, more than one day but less than one week, more than one week but less than six months, or more than six months; and frequency as once every several months, once a month, or once daily [14].

Two physiatrists conducted tailored rehabilitation education for more than two hours. These education sessions consisted of explaining the characteristics of myofascial pain syndrome, rotator cuff disorder, adhesive capsulitis, bicipital tendinitis, cervical and lumbar disc herniation, and carpal tunnel syndrome, all of which can cause musculoskeletal symptoms; stretches for each affected muscle group (cervical paraspinalis, upper trapezius, levator scapulae, rhomboideus, supraspinatus and infraspinatus, teres minor, deltoid, biceps, triceps, extensor carpi radialis, flexor carpi radialis, extensor indicis pollicis); exercise education such as rotator cuff strengthening and lumbar extension exercise; posture correction education including lifting objects, correct working posture, and improving the computer working environment using an ergonomic keyboard and mouse. In addition, we produced an educational booklet and video for continuous symptom management and uploaded the information onto a website (https://huhrd.hyumc.com/information/park.asp?cat_no=06090000) to provide subjects with continuous access to the information.

A total of 209 subjects from the original 626 were selected after history taking and physical examination. Final diagnoses were made after blood, simple radiography, electromyography, ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging testing. Based on the final diagnoses, we conducted additional tailored rehabilitation education. For example, we provided education on correct computer working posture, stretching methods, and strengthening exercises for the cervical paraspinalis muscle and upper extremity muscles to cervical herniated disc patients. For rotator cuff disorder patients, we provided education on rotator cuff stretching and strengthening exercises after education on injured rotator cuff functioning and posture that could cause impingement of the rotator cuff in order to prevent repetitive injury. If there was further need for counseling, we conducted medical counseling and tailored rehabilitation education frequently by phone, website, or e-mail (Fig. 1).

One year later, a follow-up screening survey of 316 VDT workers was performed, and the results were compared with the previous data. In addition, we determined whether there was a significant difference between the group with severe pain that was diagnosed by medical examination and the group with mild pain that was not diagnosed.

SPSS ver. 13.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for the statistical analysis. Chi-square test was used to compare the pain and no-pain groups. We used linear-by-linear association through the chi-square test to compare pain intensity, duration, and frequency of neck, shoulder, elbow, wrist, low back and lower extremity pain pre- and post-musculoskeletal rehabilitation education. We also used the independent sample t-test for comparisons between the severe and mild pain groups. The p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The mean age of the 316 VDT workers was 42.5±5.3 years, and other general characteristics such as age, gender, years of service, history of alcohol consumption and smoking, hobby, house work, physical burden of working, and region of pain are shown in Table 1.

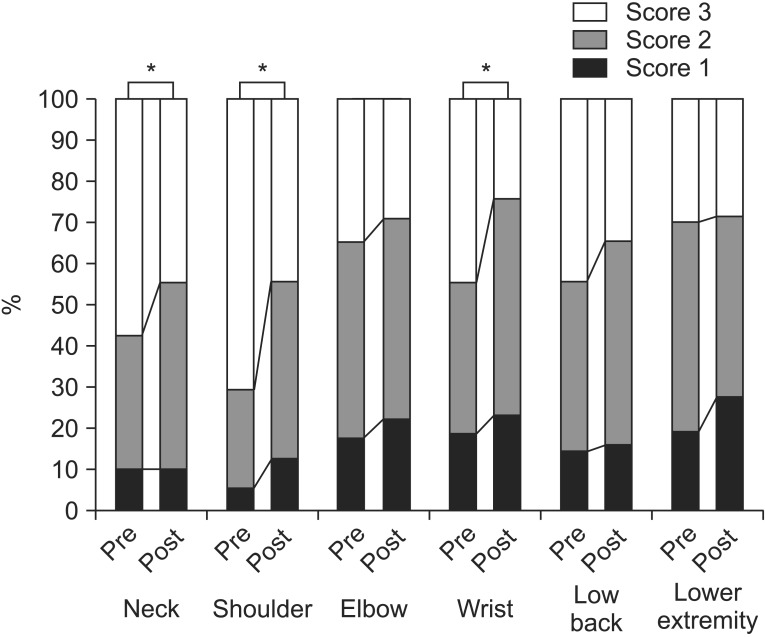

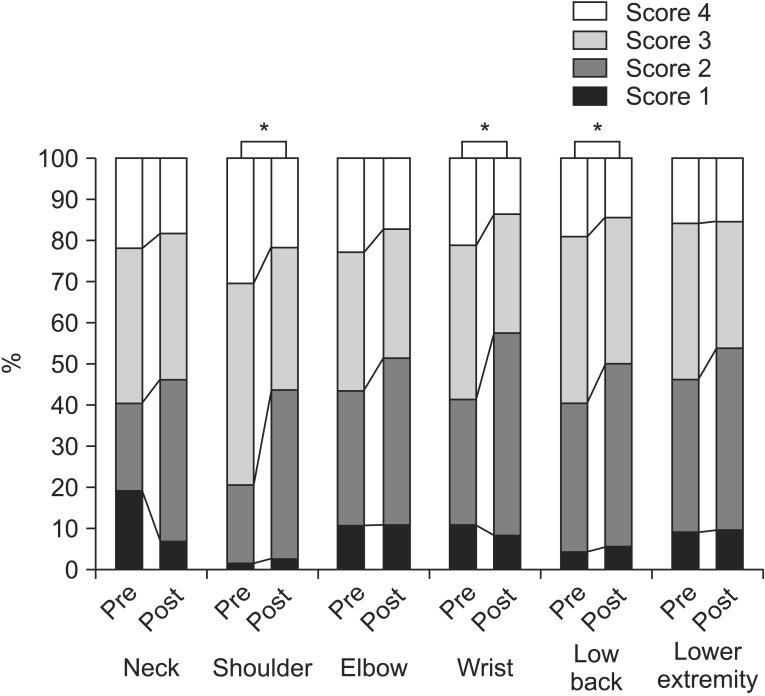

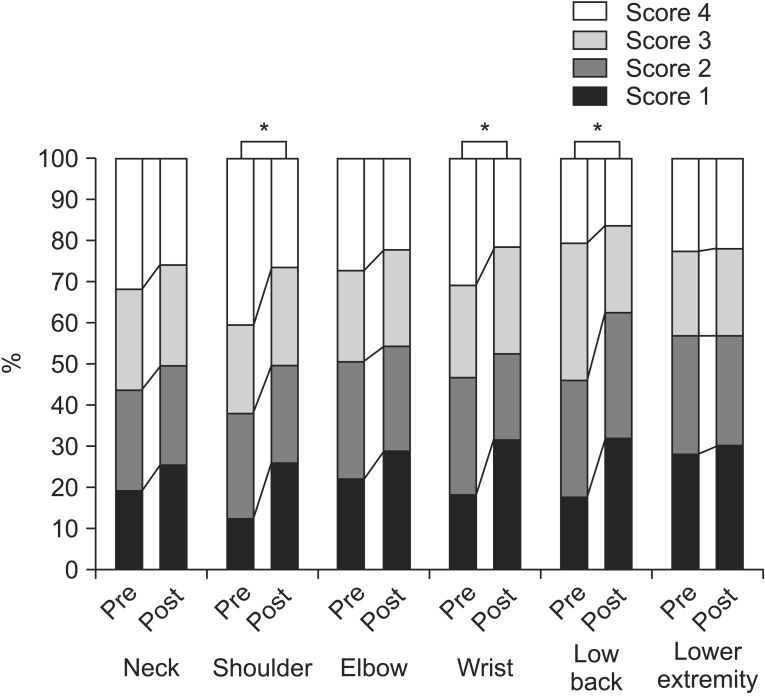

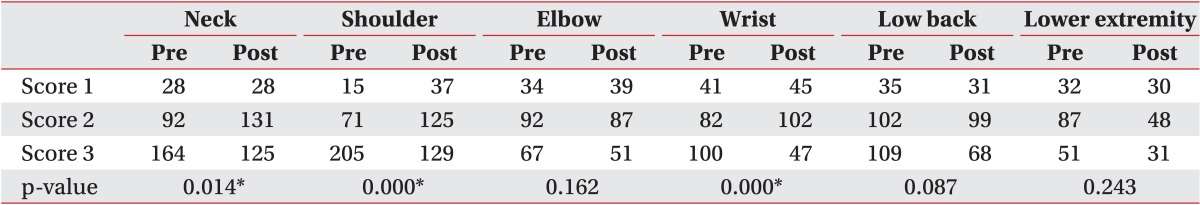

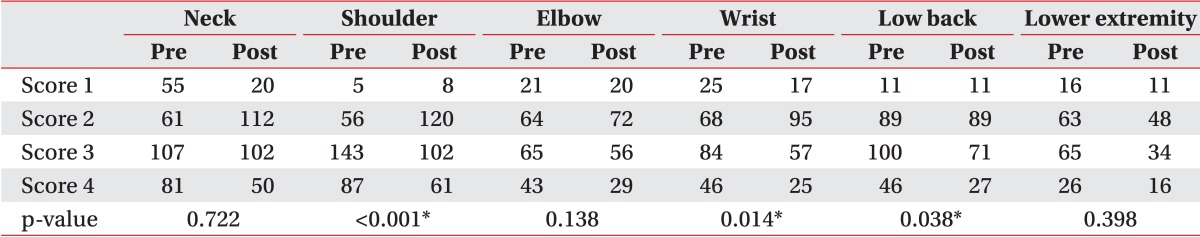

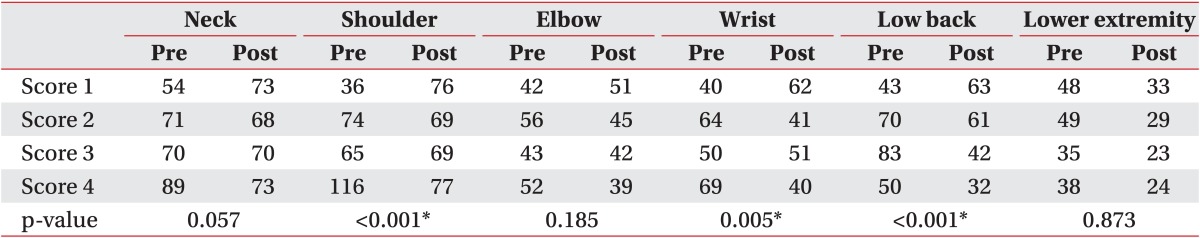

Compared with the initial survey, pain intensity was significantly decreased in the neck area (Table 3, Fig. 2); pain duration and frequency were significantly decreased in the low back area (Tables 4, 5, Figs. 3, 4); and pain duration, intensity, and frequency were significantly decreased in the shoulder and wrist after tailored rehabilitation education (Tables 3, 4, 5, Figs. 2, 3, 4). Pain duration, intensity, and frequency were also decreased in the elbow; however, there was no statistically significant difference (Tables 3, 4, 5, Figs. 2, 3, 4). No significant differences were found with regard to the lower extremities.

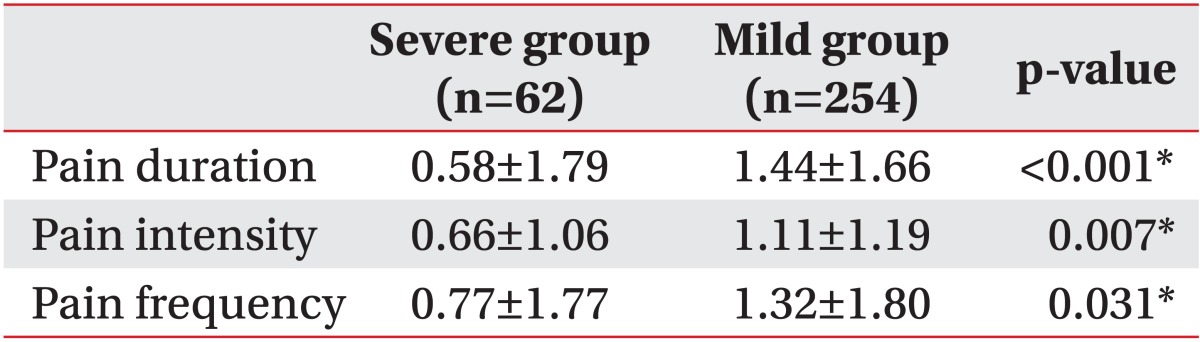

Comparing pain intensity, duration, and frequency between the severe and mild pain groups after tailored rehabilitation education revealed significantly greater decreases in pain duration, intensity, and frequency in the mild pain group compared with the severe pain group (Table 6).

The VDT workers in the present study complained of pain in the order of shoulder, neck, low back, elbow, wrist, and lower extremity. Park et al. [15] reported that the prevalence of pain complaints among 290 female international telephone operators was significantly greater in the shoulder (65.2%) and upper extremities (50.0%), followed by the neck (38.6%), low back (36.2%), hand (34.5%), back (29.0%), and lower extremities (24.8%). This study demonstrated that VDT work mainly caused shoulder-arm-neck pain. In addition, the prevalence of muscle tenderness was significantly higher in the shoulder and upper extremities, followed by the back (6.2%), neck (5.2%), low back (2.8%), hand and fingers (2.4%), and lower extremities (1.0%). In addition, muscle tenderness on the right side upper extremities, neck, and shoulder was significantly severer than it was on the left side [15].

Bernard et al. [16] reported that the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper extremities including the neck and shoulder was 41% among newspaper employees, and the prevalence of hand or wrist disorders was 22%. Bergqvist et al. [17] also found that symptom prevalence of neck and shoulder disorders was 61.2% and that the rates of neck and shoulder disorders were 22.7% and 13.0%, respectively, among VDT workers. These studies demonstrated similar results to our study, in which shoulder pain was the most common, followed by pain in the neck, low back, elbow, wrist, and lower extremities.

In a previous study related to rehabilitation education, Shuai et al. [6] evaluated the effects of an educational program for preventing work-related musculoskeletal disorders among 350 school teachers. They evaluated the program effects after 6 and 12 months using a questionnaire. The educational program contained an occupational health lecture, approximately 40 minutes long, that explained musculoskeletal disorders and risk factors and introduced ergonomic training to improve posture while at the computer. After the intervention, there was an improvement in awareness, attitudes, and behavior associated with work-related musculoskeletal disorders and a significant decrease in discomfort or pain in the neck, shoulder, and low back. These results were similar to those in our study. These results collectively suggest the importance of rehabilitation education for managing work-related musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, the educational program in the study described above was similar to that in our study with regard to explaining the characteristics of musculoskeletal disorders and education on correct working posture. However, there were differences between the studies in that additional exercise education and improvements in the working environment were provided in our study, in addition to our production of an educational booklet and video with free educational content uploaded on a website in order to increase the access to information to the subjects in our study.

de Freitas-Swerts et al. [18] evaluated the effects of office exercise on reduced work-related stress and musculoskeletal pain. They reported that there was no significant reduction in work-related stress. However, there was a significant decrease in pain in the upper, middle, and lower back; right thigh; ankle; and foot and left leg. Their study also assigned postural exercises, segmental stabilization, and segmental and muscular chain stretching for both the upper and lower extremities. This might explain the difference in results compared with our study.

However, in recent studies, no significant effects of exercise and workplace adjustments have been shown for work-related musculoskeletal pain. For example, Karjalainen et al. [9] reported that multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation showed no effectiveness on work-related musculoskeletal disorders. In addition, Verhagen et al. [10] analyzed 44 studies of 6,580 persons to examine the effects of exercise, ergonomics, and physical therapy on work-related complaints of neck, shoulder, or upper extremity discomfort. Twenty-one studies evaluated the impact of exercise on work-related musculoskeletal pain, 13 evaluated ergonomic workplace adjustments, and nine evaluated behavioral interventions and other various treatments, excluding injections and surgical procedures. All of these studies reported no effect of exercise on pain, recovery, disability, or sick leave. However, ergonomic interventions did decrease pain in the long term, although not in the short term. A possible reason for the different results compared with our study is that exercise therapy including specific forms of exercises such as proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation, Feldenkrais therapy, and Mensendieck training were provided to participants with nonspecific neck and shoulder pain, whereas we subdivided exercises into muscle-specific stretching and strengthening exercises according to actual diagnosis and conducted repeated and constant education. The results of our study including tailored rehabilitation education depending on accurate diagnosis could therefore be more clinically meaningful. In addition, to improve the working environment, we provided education on ergonomic training to improve computer working posture as a part of the tailored rehabilitation education and followed up after one year. In this regard, of our study results corresponded with those in the above meta-analysis.

Our study found that pain duration, intensity, and frequency were significantly decreased in the shoulder and wrist after tailored rehabilitation education, pain intensity was significantly decreased in the neck area and pain duration and frequency were significantly decreased in the low back area. This suggests that providing musculoskeletal rehabilitation education, including explanations of specific disease characteristics, exercise therapy, and posture education, to VDT workers is an important part of pain management. In the low back pain group, there was no significant difference in pain intensity; however, there was a decrease in the number of subjects who complained of moderate and severe pain, suggesting that musculoskeletal rehabilitation education was effective in alleviating pain intensity.

In the elbow pain group, the values of the three evaluation factors decreased, but this was not statistically significant. In the lower extremity pain group, there were no significant changes in any of the evaluation factors. A possible explanation might be that the components of our musculoskeletal rehabilitation education mainly focused on the neck, shoulder, and hand regions. With regard to the content of rehabilitation education used in our study, we think it will be necessary to revise the education so that it can be appropriately applied to all body parts, including the characteristics and symptoms of work-related musculoskeletal disorder, posture training, and exercises for the elbow and lower extremities. In the comparison between the severe and mild pain groups, pain duration, intensity, and frequency were more significantly decreased in the mild pain group than in the severe pain group. This suggests that musculoskeletal rehabilitation education was more effective in decreasing relatively mild pain, including myofascial pain syndrome. It also suggests the importance of medical examination for screening severe symptoms when planning a musculoskeletal rehabilitation education program in a large-scale work setting.

There were a number of limitations to the present study. First, this study is likely to have been influenced by the subjective tendency of respondents because of the nature of a self-report survey. To supplement this, additional study needs to be conducted with direct observation or the interview method in the future. Second, because this was a cross-sectional study, it only examined the changes in pain duration, intensity, and frequency; as such, we could not assess the effects of other psychological factors including occupational satisfaction and stress. Third, we did not consider work environment factors such as sitting position, desk height, or chair type in association with the occurrence of work-related musculoskeletal pain. Fourth, we were not able to evaluate the effects of the duration of education. Also, we did not investigate whether subjects received additional treatment other than rehabilitation education. Fifth, we were not able to set up a control group because of the nature of survey research in a large-scale work setting. In addition, many subjects were lost to follow-up. We were not able to compare the degree of decrease in pain in each body part after rehabilitation education because of the small number of subjects with pain in all body parts. Therefore, we could not analyze the region-specific effects of rehabilitation education. Large-scale prospective studies including a control group are needed in the future.

However, in spite of the above limitations, our study has clinical significance for identifying the usefulness of rehabilitation education that can easily be overlooked when analyzing symptom changes in work-related musculoskeletal patients after musculoskeletal rehabilitation education. In addition, our study differed from others in that tailored rehabilitation education was conducted according to accurate diagnosis. Therefore, our study provides useful data for establishing effective teaching methods for rehabilitating work-related musculoskeletal injury.

In conclusion, our study analyzed changes in musculoskeletal pain through disease-specific tailored rehabilitation education among VDT workers. Generally, the workers' musculoskeletal symptoms were improved after musculoskeletal rehabilitation education. In particular, there were significant decreases in pain in the shoulder, wrist, and low back regions. In addition, after musculoskeletal rehabilitation education, there was a greater decrease in pain in the mild pain group compared with the severe pain group.

References

1. Park KY, Bak KJ, Lee JG, Lee YS, Roh JH. Factors affecting the complaints of subjective symptoms in VDT operators. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 1997; 9:156–169.

2. Kwon HJ, Ha MN, Yun DR, Cho SH, Rang D, Ju YS, et al. Perceived occupational psychosocial stress and work-related musculoskeletal disorders among workers using video display terminals. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 1996; 8:570–577.

3. Kim HR, Won JU, Song JS, Kim CN, Kim HS, Roh J. Pain related factors in upper extremities among hospital workers using video display terminals. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 2003; 15:140–149.

4. Rempel DM, Krause N, Goldberg R, Benner D, Hudes M, Goldner GU. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the effects of two workstation interventions on upper body pain and incident musculoskeletal disorders among computer operators. Occup Environ Med. 2006; 63:300–306. PMID: 16621849.

5. Kim DQ, Cho SH, Han TR, Kwon HJ, Ha M, Paik NJ. The effect of VDT work on work-related musculoskeletal disorder. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 1998; 10:524–533.

6. Shuai J, Yue P, Li L, Liu F, Wang S. Assessing the effects of an educational program for the prevention of work-related musculoskeletal disorders among school teachers. BMC Public Health. 2014; 14:1211. PMID: 25422067.

7. Rodrigues EV, Gomes AR, Tanhoffer AI, Leite N. Effects of exercise on pain of musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. Acta Ortop Bras. 2014; 22:334–338. PMID: 25538482.

8. Verhagen AP, Karels C, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Burdorf L, Feleus A, Dahaghin S, et al. Ergonomic and physiotherapeutic interventions for treating work-related complaints of the arm, neck or shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006; (3):CD003471. PMID: 16856010.

9. Karjalainen K, Malmivaara A, van Tulder M, Roine R, Jauhiainen M, Hurri H, et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for neck and shoulder pain among working age adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003; (2):CD002194. PMID: 12804428.

10. Verhagen AP, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Burdorf A, Stynes SM, de Vet HC, Koes BW. Conservative interventions for treating work-related complaints of the arm, neck or shoulder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013; 12:CD008742. PMID: 24338903.

11. Kim DS, Park JG, Kim GS. The guideline of survey about risk factor relating to musculoskeletal disorders. Incheon: Korea Occupational Safety and Health Agency;2008.

12. Lee HK, Myong JP, Jeong EH, Jeong HS, Koo JW. Ergonomic workload evaluation and musculo-skeletal symptomatic features of street cleaners. J Ergon Soc Korea. 2007; 26:147–152.

13. Hwang I, Noh JI, Kim SI, Kim MG, Park SY, Kim SH, et al. Prevention of pain with the injection of microemulsion propofol: a comparison of a combination of lidocaine and ketamine with lidocaine or ketamine alone. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2010; 59:233–237. PMID: 21057611.

14. Baron S, Hales T, Hurrell J. Evaluation of symptom surveys for occupational musculoskeletal disorders. Am J Ind Med. 1996; 29:609–617. PMID: 8773721.

15. Park CY, Cho KH, Lee SH. Cervicobrachial disorders of female international telephone operators: I. subjective symptoms. Korean J Occup Environ Med. 1989; 1:141–150.

16. Bernard B, Sauter S, Fine L, Petersen M, Hales T. Job task and psychosocial risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders among newspaper employees. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1994; 20:417–426. PMID: 7701287.

17. Bergqvist U, Wolgast E, Nilsson B, Voss M. The influence of VDT work on musculoskeletal disorders. Ergonomics. 1995; 38:754–762. PMID: 7729402.

18. de Freitas-Swerts FC, Robazzi ML. The effects of compensatory workplace exercises to reduce work-related stress and musculoskeletal pain. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2014; 22:629–636. PMID: 25296147.

Fig. 1

Musculoskeletal rehabilitation education flow chart. CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; EMG, electromyography; U/S, ultrasonography.

Fig. 2

Comparison of pain intensity between pre- and post-musculoskeletal rehabilitation education (*p<0.05). Score 1, mild pain; score 2, moderate pain; score 3, severe pain.

Fig. 3

Comparison of pain duration between pre- and post-musculoskeletal rehabilitation education (*p<0.05). Score 1 indicates pain for less than one day. Score 2 represents pain for at least one day to less than one week. Score 3 indicates pain for one week to less than six months. Score 4 represents pain for longer than six months.

Fig. 4

Comparison of pain frequency between pre- and post-musculoskeletal rehabilitation education (*p<0.05). Score 1, once a year; score 2, once a month; score 3, once a week; score 4, daily.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download