Abstract

Systemic vasculitis is a rare disease, and the diagnosis is very difficult when patient shows atypical symptoms. We experienced an unusual case of dysphagia caused by Churg-Strauss syndrome with lower cranial nerve involvement. A 74-year-old man, with a past history of sinusitis, asthma, and hearing deficiency, was admitted to our department for evaluation of dysphagia. He also complained of recurrent bleeding of nasal cavities and esophagus. Brain magnetic resonance imaging did not show definite abnormality, and electrophysiologic findings were suggestive of mononeuritis multiplex. Dysphagia had not improved after conventional therapy. Biopsy of the nasal cavity showed extravascular eosinophilic infiltration. All these findings suggested a rare form of Churg-Strauss syndrome involving multiple lower cranial nerves. Dysphagia improved after steroid therapy.

Churg-Strauss syndrome (CSS) is a rare form of eosinophilic vasculitis affecting small- to medium-sized blood vessels. CSS is characterized by asthma, eosinophilia, and involvement of various organ systems including the respiratory tract, peripheral nervous system, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract. Although other forms of vasculitis have been reported as possible causative factors of cranial nerve dysfunction, there have been only two case reports of lower cranial neuropathy related to CSS. We present a rare case who presented with refractory dysphagia accompanied by gastrointestinal bleeding with multiple lower cranial nerve palsies, and finally diagnosed with antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody (ANCA)-negative CSS.

A 74-year-old man was admitted to our department for recurrent aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia that developed gradually for one year. He had been previously diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, sinusitis, and asthma. He developed insidious hearing deficiency. In addition, he had recurrent episodes of refractory oral and esophageal ulcer bleeding. Cranial nerve examination showed hearing deficiency, no gag reflex, impaired phonation, poor laryngeal elevation, impaired tongue movement, and flaccid dysarthria.

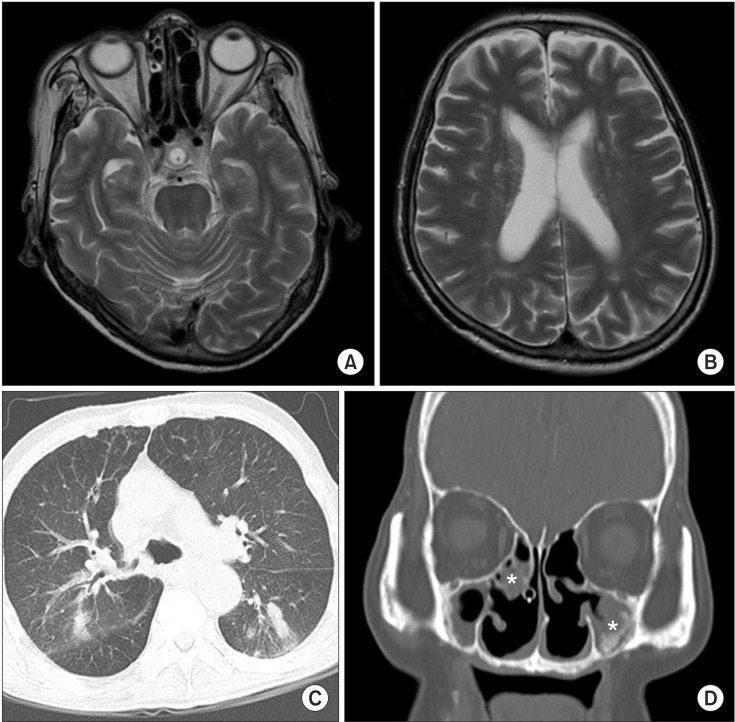

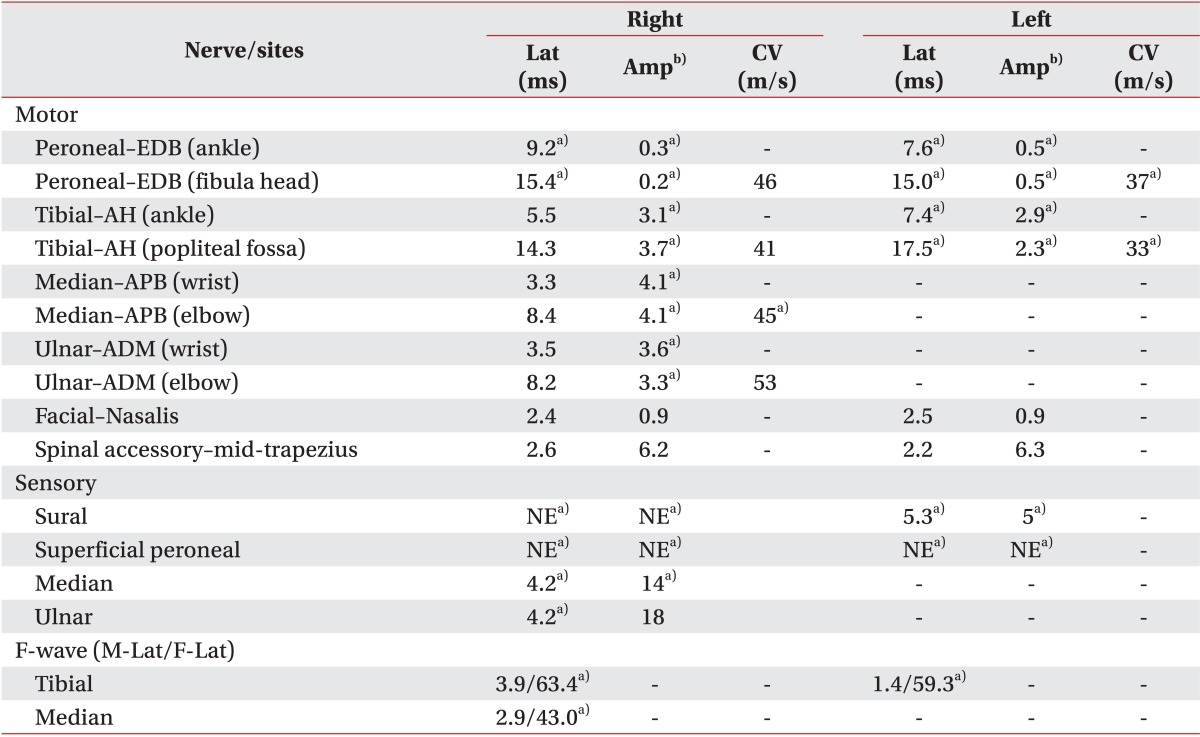

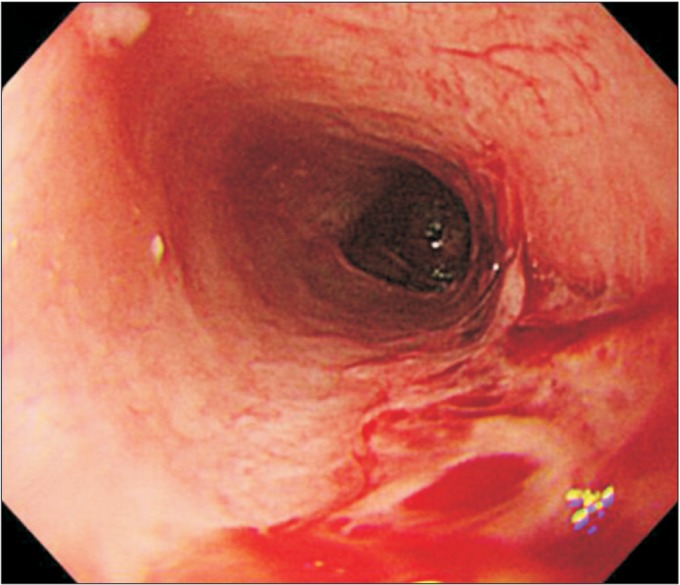

Laboratory studies on admission were nonspecific, except for mild anemia (hemoglobin 9.3 g/dL, hematocrit 29.2%) and mild eosinophilia (5.3%). Serology tests for HLA-B51 and ANCA were negative. An endoscopy detected multiple esophageal ulcers (Fig. 1). Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no definite brain lesion that might correlate with patient's dysphagia (Fig. 2A, 2B). Chest computed tomography showed focal aspiration pneumonia in right lower lobe, small centrilobular nodules in right upper lobe, and multifocal bronchiolitis in bilateral upper and lower lobes (Fig. 2C). Paranasal sinus computed tomography showed chronic sinusitis in bilateral maxillary sinuses (Fig. 2D). The pure tone average test for evaluation of hearing deficiency implied sensorineural hearing loss. Brainstem auditory evoked potential was not evoked in bilateral sides. Results of nerve conduction study and needle electromyography (EMG) were suggestive of peripheral sensory-motor polyneuropathy of mononeuritis multiplex type (Table 1).

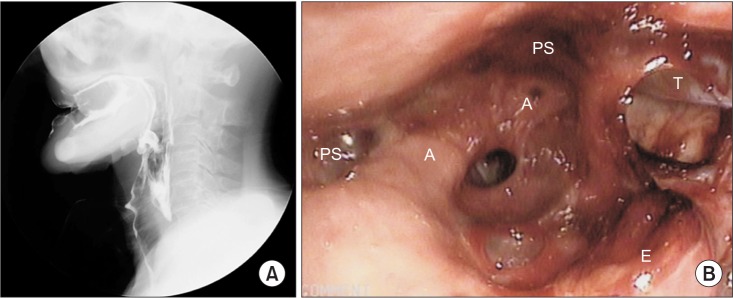

Videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) revealed delayed oral transit time with poor tongue palate contact, delayed pharyngeal trigger, and incomplete laryngeal elevation. Gross silent aspiration was observed with plain liquid with a penetration aspiration scale of 8. The patient had severe dysphagia with a functional oral intake scale of 1 (Fig. 3A). Fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES) showed a large amount of secretion in the laryngeal vestibules, and laryngeal adductor reflex (LAR) to high air pressure stimulation to both arytenoid tissues was absent. Vocal cord mobility showed decreased motion in right side but no glottis gap was detected (Fig. 3B).

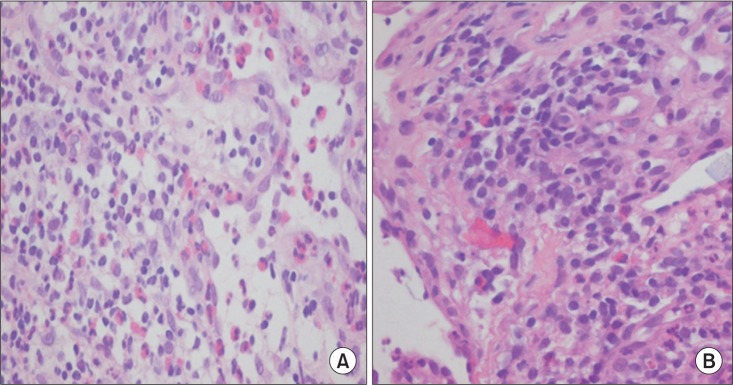

The patient's symptoms did not show any change after several weeks of dysphagia therapy. Despite these multiple signs, no definite neurodegenerative disease could be attributed to the patient's signs. To exclude systemic disorders, he was referred to the Department of Ophthalmology for evaluation and was diagnosed with uveitis. Biopsy of nasal cavity and esophagus showed vasculitis involving small sized blood vessels with extravascular eosinophilic infiltration (Fig. 4A, 4B).

Based on the past history of asthma, recurrent ulcerations of nasal cavities and esophagus, mild eosinophilia, peripheral polyneuropathy, and biopsy findings, a rare form of ANCA-negative CSS involving multiple lower cranial nerves was suspected. He began therapy with methylprednisolone and the bleeding of oral and nasal cavities showed substantial improvement. Six months later, a follow-up VFSS showed improvement of oral bolus transfer and reduced aspiration depth. Dysphagia had improved to a functional oral intake scale of 3.

Dysphagia may be related to systemic disorders including vasculitis, but their unusual clinical presentation in combination with multiple organ involvements may make proper diagnosis difficult. Our case was a rare case of dysphagia attributable to ANCA-negative CSS caused by lower cranial neuropathies. Response to therapy was good. This case is clinically relevant since it shows that conventional dysphagia therapy can be ineffective for dysphagia related to systemic disorders like vasculitis, and that treatment of the underlying systemic disorder is essential. Dysphagia can result from a wide variety of disorders, such as neurologic disorders (i.e., cerebral infarction, Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disorder, and myopathy), structural lesions, psychiatric disorders, and medications [1]. Their clinical presentation may vary according to the initial diagnosis. For example, in motor neuron disorder or myopathy, typical EMG findings of multiple denervations are present with typical motor unit action potential changes. In Parkinson's disease, patients usually show gait impairment, tremor, and bradykinesia. Our case had an unusual clinical presentation of dysphagia along with peripheral polyneuropathy and refractory oral ulcers that were responsive to steroid therapy, which indicated the probability of a systemic disorder involving multiple organs rather than a neurodegenerative disorder.

Although dysphagia has not been described as a presenting complaint of vasculitis, it has been reported in Wegener granulomatosis [2,3]. In contrast to the frequent involvement of peripheral nerves, cranial neuropathy is quite rare in CSS and only a few cases of optic, oculomotor, and facial neuropathy have been reported [4,5,6]. Moreover, lower cranial nerve palsy in CSS is extremely rare [7,8]. In contrast to past reports, our case had more debilitating dysphagia that resulted in recurrent aspiration pneumonia and tube feeding. Also, whereas past reports did not describe the nature of dysphagia in CSS, the present case determined the extent of dysphagia through VFSS and FEES assessments. Furthermore, the present case differs in that it is the first reported ANCA-negative CSS related dysphagia.

The mechanism of cranial nerve involvement in CSS is unknown. The etiology of neuropathies in CSS is thought to be related with the damage to the feeding vessels of peripheral nerves. Nerve biopsy may demonstrate epineural necrotizing vasculitis with accompanying lymphocytes and eosinophil infiltrates [9]. Likewise, we suggest that vasculitis causing ischemic damage to cranial nerves may be the potential pathophysiology. Involvement of the cranial nerve could have been confirmed through laryngeal EMG. However, as shown in the FEES image, EMG was not feasible due to continuous oropharyngeal bleeding. However, since the patient showed impaired vocal fold mobility with absence of LAR, we could assume the involvement of the cranial nerves. LAR is a mechanism of laryngeal protection. The superior laryngeal nerve and recurrent laryngeal nerve act as afferent limb and efferent limb of this reflex, respectively. Absence of LAR puts patients with dysphagia at high risk for laryngeal penetration and aspiration [10].

In conclusion, dysphagia may occur due to various causes. But, when dysphagia is accompanied by multiple medical problems, systemic diseases such as vasculitis should not be overlooked when evaluating the cause. Treatment and the prognosis of the vasculitis related dysphagia is distinct from the other neurodegenerative diseases.

References

1. Palmer JB, Monahan DM, Matsuo K. Rehabilitation of patients with swallowing disorders. In : Braddom RL, editor. Physical medicine & rehabilitation. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier;2011. p. 581–600.

2. Armani M, Spinazzi M, Andrigo C, Fassina A, Mantovan M, Tavolato B. Severe dysphagia in lower cranial nerve involvement as the initial symptom of Wegener's granulomatosis. J Neurol Sci. 2007; 263:187–190. PMID: 17658554.

3. Miller PG, Santini C, Freed MJ. Dysphagia in a patient with Wegener's granulomatosis: case report. Dysphagia. 2001; 16:136–139. PMID: 11305224.

4. Buhaescu I, Williams A, Yood R. Rare manifestations of Churg-Strauss syndrome: coronary artery vasospasm, temporal artery vasculitis, and reversible monocular blindness-a case report. Clin Rheumatol. 2009; 28:231–233. PMID: 19034601.

5. Tsuda H, Ishikawa H, Majima T, Sawada U, Mizutani T. Isolated oculomotor nerve palsy in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Intern Med. 2005; 44:638–640. PMID: 16020896.

6. Mori A, Hira K, Hatano T, Okuma Y, Kubo S, Hirano K, et al. Bilateral facial nerve palsy due to otitis media associated with myeloperoxidase-antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody. Am J Med Sci. 2013; 346:240–243. PMID: 23470272.

7. Mazzantini M, Fattori B, Matteucci F, Gaeta P, Ursino F. Neuro-laryngeal involvement in Churg-Strauss syndrome. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1998; 255:302–306. PMID: 9693926.

8. Shimada T, Sasaki R, Ii Y, Taniguchi A, Ueda Y, Tomimoto H. A case of Churg-Strauss syndrome presenting with lower cranial neuropathy. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2012; 52:507–510. PMID: 22849995.

9. Hattori N, Ichimura M, Nagamatsu M, Li M, Yamamoto K, Kumazawa K, Mitsuma T, Sobue G. Clinicopathological features of Churg-Strauss syndrome-associated neuropathy. Brain. 1999; 122(Pt 3):427–439. PMID: 10094252.

10. Aviv JE, Spitzer J, Cohen M, Ma G, Belafsky P, Close LG. Laryngeal adductor reflex and pharyngeal squeeze as predictors of laryngeal penetration and aspiration. Laryngoscope. 2002; 112:338–341. PMID: 11889394.

Fig. 2

Results of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT). T2-weighted brain MRI (A, B) in the axial view show no acute lesion or neurodegenerative change. Chest CT (C) in the axial view showed small centrilobular nodules in right upper lobe posterior segment and multifocal bronchiolitis in bilateral upper and lower lobes. Paranasal sinus CT (D) in coronal section showed mucosal thickening (asterisks) in bilateral maxillary sinuses.

Fig. 3

Results of videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) and fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing (FEES). (A) VFSS show gross silent aspiration with plain liquid. Vallecular and pyriform sinuses residues were observed. (B) FEES show a large amount of secretion in the laryngeal vestibules (A, arytenoid; PS, pyriform sinus; E, epiglottis; T, L-tube).

Fig. 4

Biopsy findings. Nasal biopsy (A) and esophageal biopsy (B) show extravascular eosinophilic infiltration (H&E, ×400).

Table 1

Results of nerve conduction studies

Lat, latency (motor, onset latency; sensory, peak latency); Amp, amplitude; CV, conduction velocity; NE, not evoked; EDB, extensor digitorum brevis; AH, abductor halluces; APB, abductor pollicis brevis; ADM, abductor digitorum minimi; M-Lat, M-wave latency; F-Lat, F-wave latency.

a)Indicates abnormal data based on our reference values.

b)Amplitudes are measured in millivolt (mV, motor) and in microvolt (µV, sensory).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download