Abstract

Spasmodic dysphonia is defined as a focal laryngeal disorder characterized by dystonic spasms of the vocal cord during speech. We described a case of a 22-year-old male patient who presented complaining of idiopathic difficulty swallowing that suddenly developed 6 months ago. The patient also reported pharyngolaryngeal pain, throat discomfort, dyspnea, and voice change. Because laryngoscopy found no specific problems, an electrodiagnostic study and videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) were performed to find the cause of dysphagia. The VFSS revealed continuous twitch-like involuntary movement of the laryngeal muscle around the vocal folds. Then, he was diagnosed with spasmodic dysphonia by VFSS, auditory-perceptual voice analysis, and physical examination. So, we report the first case of spasmodic dysphonia accompanied with difficulty swallowing that was confirmed by VFSS.

Spasmodic dysphonia is a primary task-specific focal dystonia affecting the laryngeal muscle during speech [1,2]. Patients may first notice symptoms during a period of increased stress, upper respiratory infection, or during a speech performance [3]. Spasmodic dysphonia causes voice breaks, hoarseness, and can give the voice a tight, strained quality [4]. Most people with spasmodic dysphonia have a vocal tremor, a shaking of the larynx and vocal folds that causes the voice to shake. However, symptoms like swallowing difficulty and dyspnea is rare in spasmodic dysphonia. And, the diagnosis of spasmodic dysphonia is usually confirmed by laryngoscopic examination [1]. But, this case-report documents spasmodic dysphonia confirmed through a videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS). We experienced a case in which swallowing difficulty was the main complaint and spasmodic dysphonia was diagnosed subsequently by a VFSS and auditory-perceptual voice analysis. We report this case along with the VFSS findings.

A 22-year-old male patient visited the outpatient department of otorhinolaryngology with a 6-month history of persistent difficulty swallowing after overusing his voice. The patient complained mainly of difficulty swallowing, pharyngolaryngeal pain, throat discomfort, and voice changes. He also complained of intermittent aspiration and dyspnea. He was a student teacher. He had no underlying diseases such as myopathy or motor neuron disease, and family history revealed no remarkable abnormalities. But there is a history of traumatic uvular partial amputation at a young age.

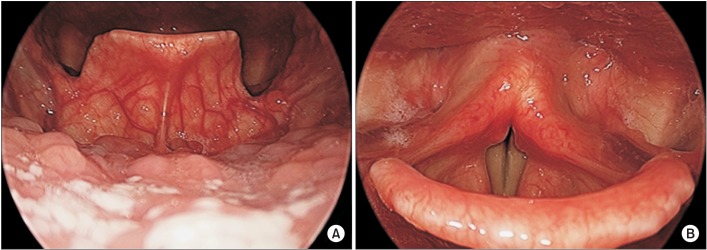

Lip and tongue movement, gag reflex, laryngeal elevation was intact, and there was no tongue deviation on physical examination. To identify a possible cause, a laryngoscopic examination was performed. Only hyperemia of both the palatine tonsil and posterior wall of the pharynx was observed by laryngoscopy (Fig. 1). The auditory perceptual voice analysis was performed to evaluate changes in the voice. An abnormally strained choked voice and voice break were observed. As for the vocalization type, it was a grade 1 (breathiness score 1 and strain score 1) on the scale of Grade Roughness Breathiness Asthenia Strain (GRBAS), so spasmodic dysphonia was suspected [5].

He was referred to the outpatient department of rehabilitation medicine for evaluation and a videofluoroscopic swallowing study. The deep tendon reflexes in all 4 extremities were normal. An electrodiagnostic study, including laryngeal electromyography was executed to rule out myotonic dystrophy. There were no abnormal findings on the electrodiagnostic study, and laryngeal electromyography had a normal pattern of muscle activation.

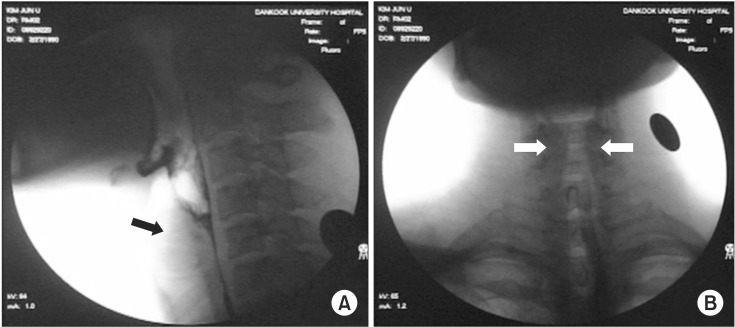

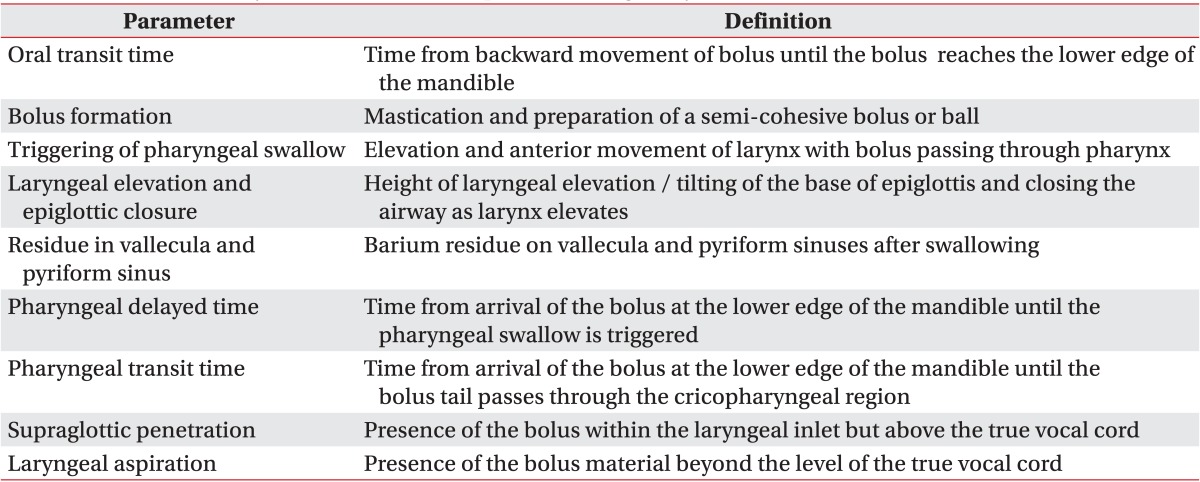

The next day, a videofluoroscopic swallowing study was carried out according to the modified Logemann method [6]. Parameters representing oropharyngeal swallowing function were analyzed while swallowing thin and thick barium liquid (Table 1). There was no penetration or aspiration on thick (200%, BaSO4) and thin (70% BaSO4) liquid swallowing. Oral transit time, pharyngeal delay time, and pharyngeal transit time were all within the normal range, but there was minimal pharyngeal residue on the vallecula area, and twitch-like involuntary movement on the laryngeal muscle around the vocal folds (Fig. 2). He did not feel this involuntary movement, which occurred before and after swallowing.

Based on the results from the VFSS findings, voice aspect, voice analysis, and physical examination, the patient was diagnosed with spasmodic dysphonia. He was scheduled for to be injected with botulinum toxin, but he did not have it done because of business obligations. He recently reported via telephone interview that there was an improvement in his voice, but the voice change reappears when he gets fatigue or speaks too much. Also, symptoms of aspiration, difficulty swallowing, and a foreign body sensation in the throat were still present.

Spasmodic dysphonia, which has also been called spastic dysphonia and laryngeal dystonia, was first described by Traube in 1871 as 'nervous hoarseness', and later referred to as 'laryngeal stuttering' [7,8]. Spasmodic dysphonia is a poorly understood voice disorder caused by an involuntary contraction of the laryngeal muscles. The etiology is unknown, but it is suspected to be caused by central nervous system disorders [2,7]. At one time it was thought to be due to a psychiatric disorder, but recently, it has been categorized as a type of focal dystonia affecting the laryngeal muscles during speech. It is also associated with the abnormal inhibitory process in sensory feedback.

Banoub et al. [9] observed that two-thirds of the cases of spasmodic dysphonia are idiopathic, whereas one third is secondary to another disorder. Physical or psychological stress can precipitate or worsen the symptom of spasmodic dysphonia. Pool et al. [10] reported that 70% of patients with spasmodic dysphonia had neurologic abnormality, including tremors, weakness, movement abnormalities, and dystonia in other muscle groups. In our case, the patient is a student teacher who is asked to speak daily, and has a history of overusing his voice. It is likely that the stress of speaking daily aggravated his symptoms.

Most patients have shaking of the larynx and vocal folds that causes the voice to shake. In this case, the patient's main complaint was difficulty swallowing, but it has not yet been reported in spasmodic dysphonia. Normally, the larynx serves primarily as a valve to keep food from entering the airway during swallowing. The laryngeal muscles pull the larynx upwards to assist in this process [6]. We speculate that the patient's difficulty swallowing was caused by incoordination between laryngeal elevation and closing of the glottis. Laryngeal muscles consist of intrinsic and extrinsic muscles. The intrinsic muscles include the posterior cricoarytenoid, arytenoid, cricothyroid, thyroarytenoid, which are responsible for controlling sound production. The extrinsic muscles consist of mainly the thyrohyoid and stylohyoid, which are responsible for supporting and positioning the larynx [6]. Traditionally, most cases of spasmodic dysphonia mainly involve the intrinsic muscles, but in this case the authors think that both the intrinsic and extrinsic are involved. The irregular spasm of these laryngeal muscles may have disturbed the organized swallowing and respiratory process, resulting in difficulty swallowing and symptoms of aspiration. This explains the patient's complaints of simultaneous dysphagia and voice break.

In the diagnosis of spasmodic dysphonia, a three-tiered approach was recommended: 1) screening questions to suggest possible spasmodic dysphonia, 2) a speech examination to identify probable spasmodic dysphonia, and 3) laryngoscopy for a definite diagnosis [1]. Spasmodic dysphonia can be also diagnosed by physical examination and laryngeal muscle electromyography. However, there is no specific test or gold standard for diagnosing spasmodic dysphonia yet, although laryngoscopy is known to be the most accurate test.

In this case, there were no abnormal findings on laryngoscopy. The larynx can appear anatomically normal on laryngoscopy and the symptoms of spasmodic dysphonia can fluctuate based on the amount of stress and phonation. Moreover, spasmodic dysphonia was subsequently diagnosed by VFSS in our case. Although there are many methods for diagnosing spasmodic dysphonia, VFSS can be one diagnostic tool, especially in cases of involuntary movement of the laryngeal muscles around vocal folds associated with voice change and difficulty swallowing.

The limitation of this study is that the authors did not present complete diagnostic and treatment course, and the laryngoscopy was not performed in various situations. Further studies are needed to investigate the efficacy of treatment, including botulinum toxin injection based on VFSS. Furthermore, we would have preferred to perform a laryngoscopic evaluation with the laryngeal muscle under stress and at rest.

This is the first report in which spasmodic dysphonia was accompanied by difficulty swallowing, which was confirmed by VFSS. The authors recommend VFSS as one of the diagnostic tests for patients with spasmodic dysphonia accompanied with difficulty swallowing.

References

1. Ludlow CL, Adler CH, Berke GS, Bielamowicz SA, Blitzer A, Bressman SB, et al. Research priorities in spasmodic dysphonia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008; 139:495–505. PMID: 18922334.

3. Miler RH. Technique of percutaneous EMG-guided botulinum toxin injection of the larynx for spasmodic dystonia. J Voice. 1992; 6:377–379.

4. Davis PJ, Boone DR, Carroll RL, Darveniza P, Harrison GA. Adductor spastic dysphonia: heterogeneity of physiologic and phonatory characteristics. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1988; 97(2 Pt 1):179–185. PMID: 3355046.

5. Yu P, Ouaknine M, Revis J, Giovanni A. Objective voice analysis for dysphonic patients: a multiparametric protocol including acoustic and aerodynamic measurements. J Voice. 2001; 15:529–542. PMID: 11792029.

6. Logemann JA. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. 2nd ed. Austin: Pro-Ed;1998.

7. Blitzer A, Brin MF. Laryngeal dystonia: a series with botulinum toxin therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1991; 100:85–89. PMID: 1992905.

8. Kieschnick CO, Powell TW. Treatment of spasmodic dysphonia: a brief overview for clinicians. Natl Stud Speech Lang Hear Assoc J. 1996; 23:14–18.

9. Banoub M, Rao U, Motta P, Tetzlaff JE, Eliachar I, Blitzer A. Recurrent postoperative stridor requiring tracheostomy in a patient with spasmodic dysphonia. Anesthesiology. 2000; 92:893–895. PMID: 10719977.

10. Pool KD, Freeman FJ, Finitzo T, Hayashi MM, Chapman SB, Devous MD Sr, et al. Heterogeneity in spasmodic dysphonia: neurologic and voice findings. Arch Neurol. 1991; 48:305–309. PMID: 2001189.

Fig. 1

Laryngoscopic examination. (A) Tongue base and epiglottis. There was no swelling around tongue base. (B) Vocal fold. Vocal fold was symmetric, mild hyperemia is only observed around vocal fold and aryepiglottic fold.

Fig. 2

(A) Videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) lateral view. Twitch-like involuntary movement (black arrow) in laryngeal muscles around vocal fold. (B) VFSS anterior-posterior view. Involuntary movement was also observed (anterior-posterior view, white arrow). This movement occurred before or after swallowing.

Table 1

Parameters analyzed in videofluoroscopic swallowing study

The definitions are based on Logemann [6].

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download