Abstract

Objective

To clarify how participation in leisure activities and exercise by chronic stroke survivors differs before and after a stroke.

Methods

Sixty chronic stroke survivors receiving community-based rehabilitation services from a health center in Seongnam City were recruited. They completed a questionnaire survey regarding their demographic characteristics and accompanying diseases, and on the status of their leisure activities and exercise. In addition, their level of function (Korean version of Modified Barthel Index score), risk of depression (Beck Depression Inventory), and quality of life (SF-8) were measured.

Results

After their stroke, most of the respondents had not returned to their pre-stroke levels of leisure activity participation. The reported number of leisure activities declined from a mean of 3.9 activities before stroke to 1.9 activities post-stroke. In addition, many participants became home-bound, sedentary, and non-social after their stroke. The most common barriers to participation in leisure activities were weakness and poor balance, lack of transportation, and cost. The respondents reported a mean daily time spent on exercise of 2.6±1.3 hours. Pain was the most common barrier to exercise participation.

Stroke is one of the three most common causes of death along with malignant tumors and cardiovascular diseases. Stroke-related morbidity is rapidly increasing as the prevalence of adult diseases grows due to increased average life expectancy and improved dietary and environmental changes. The prevalence of stroke is also gradually increasing in young patients. With advances in medical technologies, the number of disabled persons who experience strokes is also gradually increasing as the rate of survivors after a stroke increases [1,2,3].

Patients with chronic stroke are hospitalized during the acute or sub-acute phase, and then receive rehabilitation treatment. However, after their discharge, they do not receive continuous rehabilitation treatment in their community. The number of stroke survivors using community-based public health rehabilitation services is also low. Patients with chronic stroke can also be restricted from participating in various activities due to the sequelae of stroke. Accordingly, they lead a lifestyle with less mobility and limited participation in leisure activities as compared to the lifestyles of healthy adults. This can herald secondary health problems, such as deterioration of quality of life (QoL) and mental health.

This study investigated the current availability of community rehabilitation services and limitations to service provision by surveying the leisure activities and exercise participation in chronic stroke patients receiving community rehabilitation services in two public health centers in Korea.

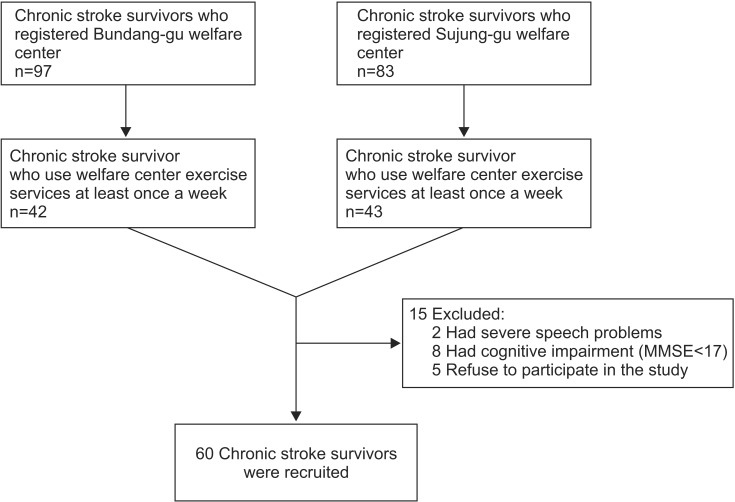

The study recruited 180 subjects with brain lesions registered at the Bundang-gu Public Health Center (n=83) and Sujung-gu Public Health Center (n=97), both located in Sungnam City. On average, 42 and 43 subjects rehabilitation services at Bundang-gu and Sujung-gu center, respectively, one or more times a week from May to August 2013. These 85 patients were evaluated for inclusion using the following criteria: patients diagnosed with stroke and who had a stroke-related disorder for at least two years, community residents who had visited the Bundang-gu or Sujung-gu Public Health Centers at least once a week, and patients with a Korean version of Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) score of 17 and who could communicate. Sixty subjects (37 males and 23 females) participated in this study (Fig. 1).

Age, gender, education, marital status, insurance coverage, disorder type, causative disease, disease period, concurrent disease, and treatment were reviewed.

A pilot study was conducted on 10 randomly selected stroke patients to survey their exercise and leisure activities. Leisure time was defined as time when free activities were performed, separate from essential time (working, eating, and sleeping). Most of the participants considered exercise, such as self-exercise using instruments in public health centers and outdoor walking, essential treatments rather than leisure activities. Accordingly, self-exercise was separated from leisure activities in this study, although sport activities are generally included in leisure activities.

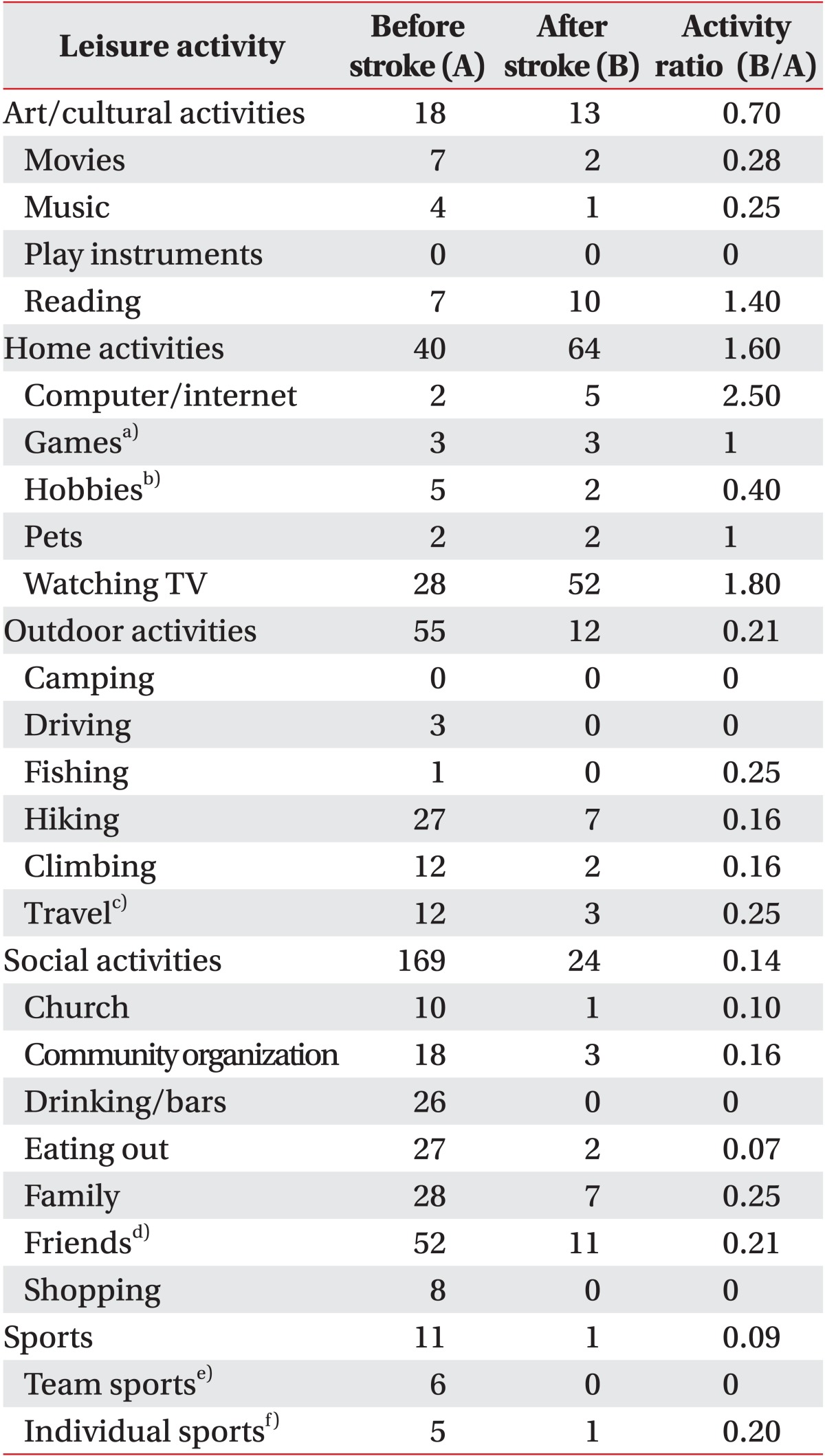

To compare the subjects' participation in leisure activities before and after stroke, a survey was performed based on the Functional Status Examination (FSE) [4]. FSE is a tool for determining how daily activities functionally change after a disease. The subjects were asked to answer questions concerning their leisure activities before stroke, current continuation of leisure activities and the need for help from others to do so, and new leisure activities begun after their stroke. Leisure activities identified by the subjects were classified into the five previously reported [5] categories of art/cultural activities, home activities, outdoor activities, social activities, and sports activities. The questionnaire was developed based on this classification. To examine changes in post-stroke leisure activities, the activity ratio was determined by dividing the number of patients who performed each post-stroke leisure activity by the number of patients who performed such leisure activities before their stroke.

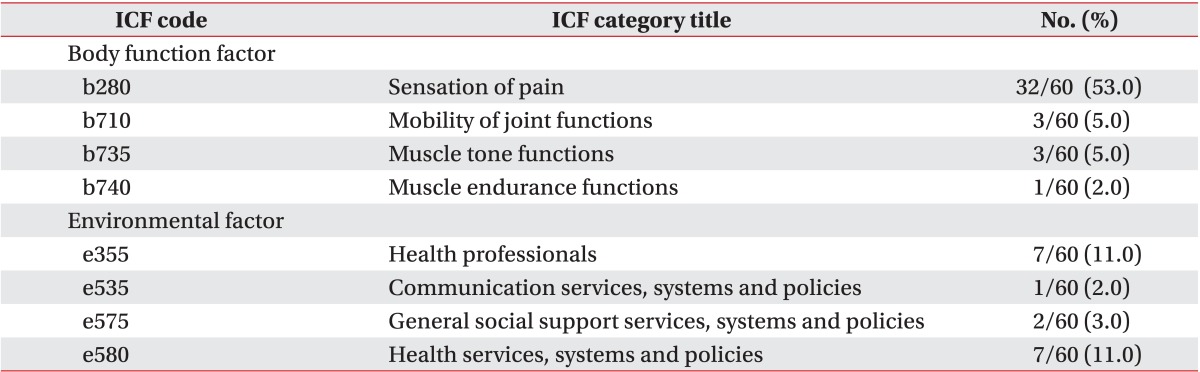

A preliminary study was conducted on subject participation in exercise to examine the duration, intensity, and type of exercise. Also, based on the body function factors and environmental factors of the comprehensive International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Set for stroke, barriers to participation in exercise and leisure activities were determined [6,7]. Seven body function factors and six environmental factors were identified in the preliminary study and the final questionnaire was developed based on these factors. The 60 stroke patients were surveyed using the prepared questionnaire. In addition, a cognitive function test was conducted using the K-MMSE, a functional level test was conducted using the Korean version of Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI), and the degree of depression and QoL were measured using Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and the Short Form 8 (SF-8), respectively [8,9]. The questionnaire was administered by a single rehabilitation professional through interviews with the patients.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to determine the correlation of the number of leisure activities and the exercise duration after a stroke with the patient's age, QoL, degree of depression, living independence, SF-8 score, B DI score, K-MBI score, and time elapsed after the stroke, using Spearman rank correlation coefficients. A Student t-test was performed to examine the relationship of the patient's gender with the number of leisure activities and exercise duration. ANOVA was performed to examine the relationship of the patient's educational attainment with his or her number of leisure activities and exercise duration. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

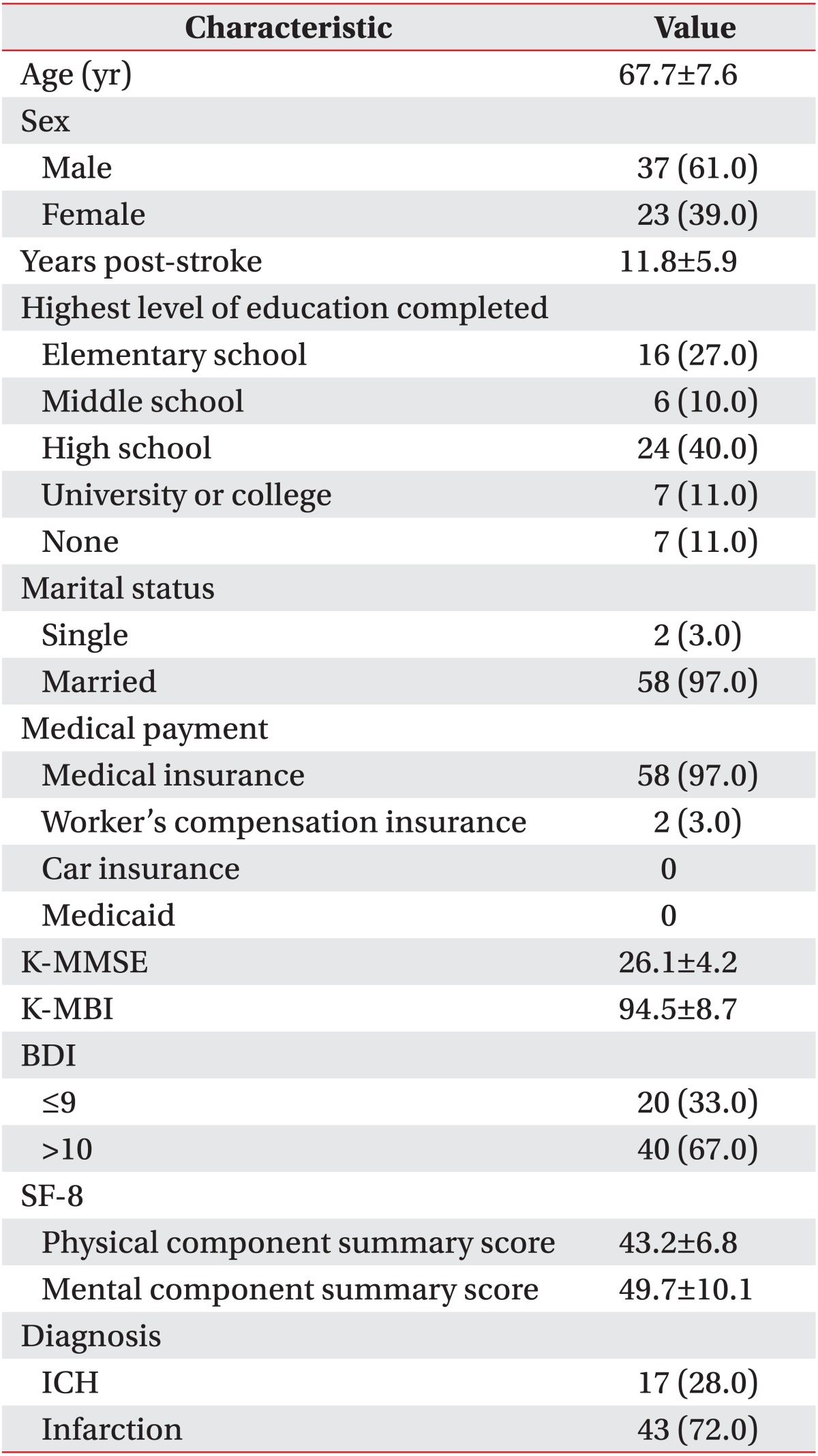

The mean age was 67.7±7.6 years. Thirty-seven were men and 23 were women. The majority were high school graduates (n=24, 40%) and elementary school graduates (n=16, 27%). Fifty-eight subjects (97%) were married and only two (3%) were single. Fifty-eight subjects (97%) had health insurance and two (3%) had industrial hazards insurance. Seventeen subjects (28%) had experienced a cerebral hemorrhage and 43 (72%) had undergone an ischemic stroke. Mean disease duration was 11.8±5.9 years (range, 2-26 years). All subjects had been hospitalized at one or more hospitals for stroke treatment, after which they returned to their community. Fifty-two had a K-MMSE score ≥24 (mean, 26.1±4.2), and 17 had a K-MBI score of 100 (mean, 94.5±8.7), indicative of better cognitive functions and daily living independence than in the 2011 Survey of the Disabled conducted by Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs [19]. In order to visit the public health centers, 36 subjects (60%) walked, 15 (25%) used public transportation (subways or buses), six (10%) used motor scooters, and three (5%) drove themselves in cars. The mean BDI was 7.42±5.85 and 20 patients had a BDI score ≥10. Concerning the SF-8 score, the Physical Component Summary score 8 (PCS-8) was 43.2±6.8 and the Mental Component Summary score 8 (MCS-8) was 49.7±10.1 (Table 1).

Concerning concurrent condition, 17 subjects had diabetes, 40 had hypertension, and eight had hyperlipidemia, renal failure, and arrhythmia, with some subjects having more than one concurrent condition. Of these, 56 patients (94%) were taking medications (the remaining four patients had no concurrent diseases). Thirty-nine subjects (65%) experienced musculoskeletal pain in the shoulder (n=13), knee (n=14), hip and lumbar region (n=12). The cause and diagnosis of the musculoskeletal pain was known in four subjects (10%), but the other 35 (90%) had idiopathic pain. As the majority of the subjects considered pain an incurable sequelae of stroke, they were unaware of the need for its proper assessment and treatment. Of those who suffered from musculoskeletal pain, only 11 subjects (28%) visited the hospital to receive proper treatment. Twenty-eight subjects (72%) did not undergo proper examination and treatment; reasons included tolerable pain (n=15, 53%), lack of transportation (n=6, 21%), and prohibitive treatment cost (n=6, 21%). Regarding the need for regular visits to the hospital, 54 subjects (88.5%) responded that they needed to visit the hospital for drug prescriptions for their concurrent diseases. However, only two subjects (3%) replied that they needed to visit the hospital to have their musculoskeletal pain treated. In the analysis of the correlation of the SF-8 score and the BDI score with the patients with and without pain, the patients with pain showed significantly lower SF-8 scores and higher BDI scores (p<0.05).

After their stroke, all subjects had difficulty participating in leisure activities. Among them, one subject (1.6%) needed help to participate in leisure activities, yet maintained the frequency of participation in leisure activities and did not change the types of leisure activities. The remaining 59 subjects (98.4%) had reduced the frequency of their participation in leisure activities. The mean number of the types of leisure activities engaged in prior to and following stroke was 4.9 and 1.9, respectively. Nine (15%) of the subjects were satisfied with their participation in leisure activities. Twenty percent of the subjects engaged in cultural leisure activities, 91% engaged stay-at-home activities (such as TV viewing), 16% engaged in outdoor activities, and 38% in social activities. Comparison of the leisure activities before and after stroke determined that the frequencies of drinking-related leisure activities and social or outdoor activities like travel and sports were significantly reduced after stroke (Table 2). The factors that interrupted participation in current leisure activities were examined to determine the causes of the reduced participation in leisure activities. Major body function and environmental causes included muscle weakness and transport inconvenience and policies, respectively (Table 3).

A small minority (1.6%) of the respondents were satisfied with their participation in leisure activities with the help of charities and social enterprises. Regarding the preferred leisure activities, 56% of the respondents wanted to participate in outdoor activities, such as travel, or social activities, such as meeting with friends or family. The frequency of participation in leisure activities was positively correlated with the K-MBI score (r=0.341, p=0.008), K-MMSE score (r=0.432, p=0.001), PCS-8 score of the SF-8 score (r=0.480, p=0.000), and MCS-8 score of the SF-8 score (r=0.330, p=0.010), but was negatively correlated with age (r=-0.360, p=0.005) and the BDI score (r=-0.282, p=0.029). No correlation was found between the frequency of participation in leisure activities and disease duration, educational attainment, or gender.

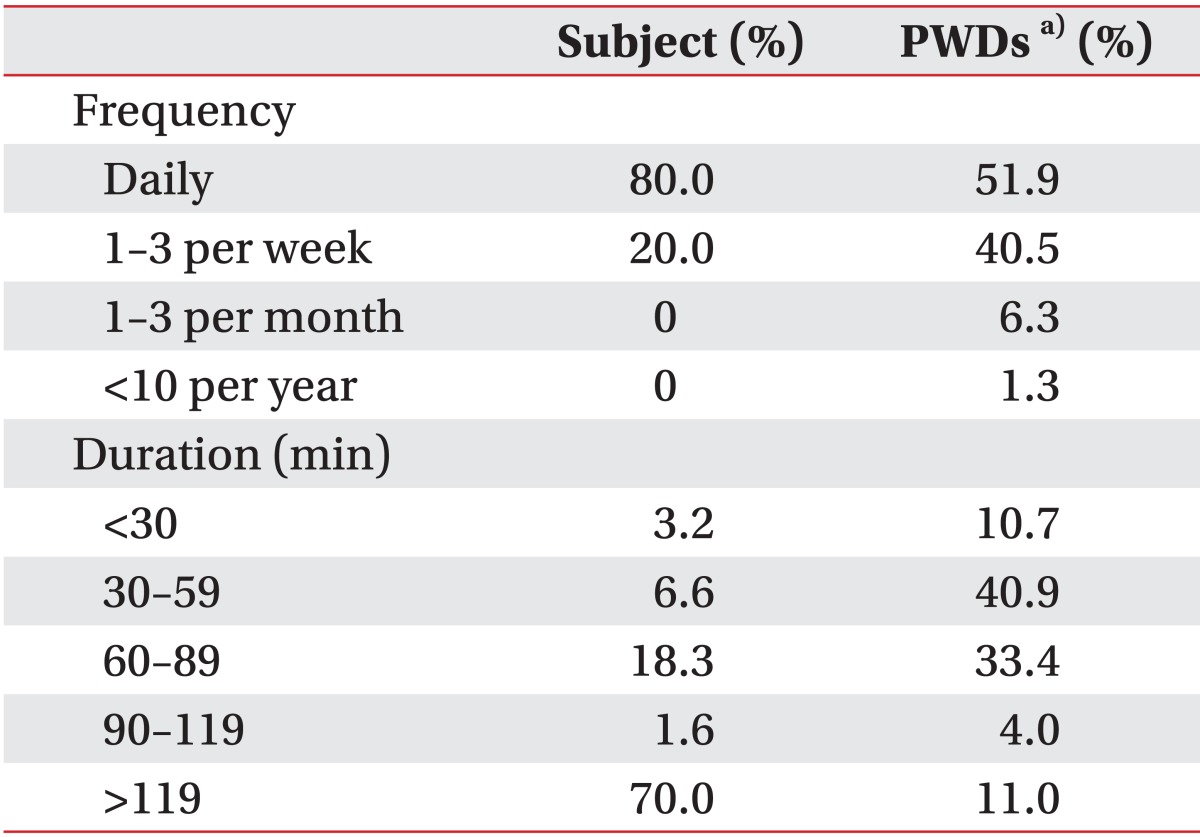

The exercise cycle for the past month was examined in the patients with chronic stroke who visited the public health centers. Daily exercise visits comprised 51.9% of subjects, with 40.5% exercising one to three times a week. Exercise duration per visit was 30-60 minutes (1.6%), 60-90 minutes (5.0%), 90-120 minutes (11.7%), and ≥120 minutes (81.7%). The mean exercise duration per visit was 2.6±1.3 hours, which was longer than the mean exercise duration of 55.3 minutes from the 2011 Survey of the Disabled (Table 4). Exercise duration was positively correlated with the MCS-8 score of the SF-8 score (r=0.369, p<0.05). It was negatively correlated with the BDI score, but the correlation was statistically insignificant (r=-0.238, p=0.067). In addition, no correlation was found between exercise duration and age, K-MMSE score, K-MBI score, PCS-8 score of the SF-8 score, or disease duration.

The most common exercise locations were the public health centers and parks. The exercise intensity measured using the Borg scale was 10 (n=52), 8 (n=6), and 12 (n=2).

Seventeen subjects (28%) reported no barriers to exercise, with 43 (74%) indicating that they faced barriers. The most frequently selected barriers were pain and impediments in health services, systems, and policies (Table 5).

Most people participate in leisure activities to enhance their mental and physical health. For stroke patients who are unable to go back to work due to disorders caused by their stroke, leisure activities are particularly important [10,11]. Participation and satisfaction in leisure activities enhances QoL. Leisure activities increase physical health, confidence, and QoL of stroke patients [12,13,14,15]. Community-based leisure activity programs enhance QoL of stroke patients [16].

This study was conducted to investigate the status of participation in leisure activities by patients with chronic stroke who visited public health centers. The types and frequency of leisure activities were significantly reduced after the stroke. A comparison of the leisure activities before and after stroke showed that watching concerts or shows among the cultural activities, travelling among the outdoor activities, meeting friends or family among the social activities, and team sports like soccer among the sports activities were the most significantly reduced. However, among indoor activities, the frequencies of participation in gardening and pet keeping decreased, but TV watching and computer use increased.

The majority of the respondents participated in leisure activities that require less mobility and that can be done alone, compared to those engaged in before their stroke. Furthermore, they were dissatisfied with this change in their participation in post-stroke leisure activities. This result is consistent with previous reports that stroke patients find it difficult to participate in active leisure activities [17,18]. In this study, the barriers to current participation in leisure activities were examined based on the ICF Core Set to determine the causes of the reduction in the frequency of leisure activities after the stroke. The b730 muscle power function and e540 transportation services, systems, and policies were selected as the most prominent barriers to participation. Prior studies have reported that participation in leisure activities is affected by transportation availability and the support of family and friends, and that reduced function and nervousness over other people's attention due to the stroke restricts leisure activity participation [12,14].

Gait disturbance and difficulty using of public transportation due to muscle weakness and a reduced sense of balance caused by the stroke were the most significant factors in the restriction of participation in various leisure activities. Difficulty in engaging in new hobbies and forming new relationships due to a decreased confidence caused by muscle weakness also restricted participation in leisure activities. In addition, a majority of the respondents had stopped participating in leisure activities, such as drinking. This change was likely to have positively affected the patient's health. However, it reduced participation in social leisure activities.

Chronic stroke patients who reported limited participation in various activities due to their deteriorated physical function after their stroke spent most of their time staying at home or exercising in public health centers. In this study, the mean exercise duration per visit was 156 minutes, which was longer than the mean exercise duration of 55 minutes from the 2011 Survey of the Disabled conducted by the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) [19]. This result contradicts a previous finding of significantly reduced exercise duration in stroke patients [20]. The dichotomous findings likely reflect the use of differing study populations; this study was conducted only on chronic stroke patients who visited the public health centers. In this study, the b280 sensation of pain among the body function factors and the e580 health services, systems, and policies among the environmental factors were selected as the most significant barriers for participating in exercise. Rimmer et al. [20] reported that the cost problem, the lack of exercise knowledge, and the lack of an appropriate exercise place were barriers to exercise participation in stroke patients. Shaughnessy et al. [21] reported that confidence, expectation of outcomes, and the degree of exercise participation before the stroke affected exercise participation after the stroke. This difference in the barriers to exercise participation is attributed to the differences between the community rehabilitation treatment systems of Korea and other countries, and the fact that this study was conducted on stroke patients who visited public health centers.

Presently, participation in aerobic exercises, such as walking in the park, and the duration of their indoor muscle exercises using machines increased, but participation decreased in sport activities like soccer and badminton performed prior to stroke. Compared to the status of pre-stroke leisure activities, types and intensities of exercises decreased, but overall exercise duration increased due to the increased aerobic and muscle exercises. This was likely because the respondents performed their aerobic exercises and muscle exercises at a mild intensity for a longer time in the public health centers due to the reduction of their participation in leisure activities. Subjects replied that they performed the exercises without satisfaction, and that they viewed aerobic exercises or muscle exercises after their strokes as rehabilitation treatments. These long-term exercises are likely to increase their risk of musculoskeletal pain and to restrict their participation in other leisure activities.

In this study, pain was judged the most significant barrier to exercise participation. Pain was likely to be caused by arthritis, central pain, spasticity, and complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS). In another study, the rate of pain increased after stroke, necessitating and that proper management [22]. Post-stroke pain can significantly diminish QoL [23]. However, in this study, visiting the hospital due to pain after a stroke was considered unnecessary, which led to improper assessment and treatment. The majority of the respondents considered their pain to be a natural result of their stroke, and did not undergo accurate diagnosis and treatment. In addition, they showed no interest in participating in other leisure activities. They selected 'lack of exercise places' and 'lack of knowledge on how to exercise' as barriers to their exercise participation, and indicated that they hoped to spend more time exercising.

A wide range of health services, such as continuous monitoring of chronic diseases, medication, community rehabilitation treatment, regular health examination, various types of preventive diagnosis, and health promotion, should be required for the disabled, as should enhancement of primary medical care for the disabled by rehabilitation specialists who thoroughly understand the characteristics of the disabled [24]. Thus, support from rehabilitation specialists is required to help stroke patients who suffer from chronic pain and who visit public health centers for exercise participation to increase their medical care services and learn the proper exercise method, intensity, and duration.

Compared to the status of the respondents' participation in leisure activities before their stroke, the number of their post-stroke leisure activities was reduced due to muscle weakness, limited approaches, lack of information, and financial problems. The patients spent most of their time daily engaged in leisure activities, such as TV watching and exercising in the public health centers. Financial support and institutional support for leisure activity participation and relevant information in public health centers are required to encourage stroke patients in communities to participate in various leisure activities. Development of community-based leisure activity participation programs to encourage stroke patients to participate in leisure activities in places other than public health centers is required to improve the QoL of chronic stroke patients by enhancing their satisfaction with and confidence in engaging in leisure activities, and their sociability.

This study had a few limitations. First, stroke patients who visited the Bundang-gu and Sujung-gu Public Health Centers in Sungnam City were included in this study without considering their level of function or cognitive function differences. Thus, it is difficult to generalize the results of this study. Second, the effects of the patients' economic status, age, gender, functional level, and cognitive function on their leisure activities were not considered. Further studies need to consider these factors. Third, there was a problem with the definition of leisure activities. The time spent exercising in the public health center was not included in the leisure time. This was because a majority of the respondents considered exercises to be rehabilitation treatments rather than leisure activities, and viewed sports activities, such as soccer, as leisure activities. Accordingly, the time spent in sports activities was included in the leisure time in order to avoid confusion. Fourth, without the proper assessment and diagnosis of the patients' pain, pain was assessed based on the subjective symptoms disclosed by the patients.

In conclusion, this study revealed significant decreases in the type and frequencies of the leisure activities, and an increase in the exercise duration of chronic stroke patients who visited public health centers in their community. These changes were associated with the subjects' decreased QoL. Establishment of a public health policy and services department for the provision of information and education on proper leisure activities for chronic stroke patients will help improve their QoL.

References

1. Granger CV, Sherwood CC, Greer DS. Functional status measures in a comprehensive stroke care program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1977; 58:555–561. PMID: 597021.

2. Kwon HK, Oh CH. Clinical study of stroke. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 1984; 8:83–91.

3. Lee KM. Rehabilitation treatment of C.V.A. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 1977; 2:84–86.

4. Dikmen S, Machamer J, Miller B, Doctor J, Temkin N. Functional status examination: a new instrument for assessing outcome in traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2001; 18:127–140. PMID: 11229707.

5. Wise EK, Mathews-Dalton C, Dikmen S, Temkin N, Machamer J, Bell K, et al. Impact of traumatic brain injury on participation in leisure activities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010; 91:1357–1362. PMID: 20801252.

6. Rimmer JH. Use of the ICF in identifying factors that impact participation in physical activity/rehabilitation among people with disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2006; 28:1087–1095. PMID: 16950739.

7. Geyh S, Cieza A, Schouten J, Dickson H, Frommelt P, Omar Z, et al. ICF Core Sets for stroke. J Rehabil Med. 2004; (44 Suppl):135–141. PMID: 15370761.

8. Alguren B, Lundgren-Nilsson A, Sunnerhagen KS. Facilitators and barriers of stroke survivors in the early post-stroke phase. Disabil Rehabil. 2009; 31:1584–1591. PMID: 19479517.

9. Kosinski M, Dewey JE, Gandek B. How to score and interpret single-item health status measures: a manual for users of the SF-8 health survey. Lincoln, RI: QualityMetric Inc.;2001.

10. Kinney WB, Coyle CP. Predicting life satisfaction among adults with physical disabilities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992; 73:863–869. PMID: 1387523.

11. Teasdale TW, Engberg AW. Subjective well-being and quality of life following traumatic brain injury in adults: a long-term population-based follow-up. Brain Inj. 2005; 19:1041–1048. PMID: 16263647.

12. Jongbloed L, Morgan D. An investigation of involvement in leisure activities after a stroke. Am J Occup Ther. 1991; 45:420–427. PMID: 2048623.

13. Parker CJ, Gladman JR, Drummond AE, Dewey ME, Lincoln NB, Barer D, et al. A multicentre randomized controlled trial of leisure therapy and conventional occupational therapy after stroke. Clin Rehabil. 2001; 15:42–52. PMID: 11237160.

14. Nour K, Desrosiers J, Gauthier P, Charbonneau H. Impact of a home leisure educational program for older adults who have had a stroke (home leisure educational program). Ther Recreat J. 2002; 36:48–64.

15. Specht J, King G, Brown E, Foris C. The importance of leisure in the lives of persons with congenital physical disabilities. Am J Occup Ther. 2002; 56:436–445. PMID: 12125833.

16. Parker CJ, Gladman JR, Drummond AE. The role of leisure in stroke rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 1997; 19:1–5. PMID: 9021278.

17. Desrosiers J, Bourbonnais D, Noreau L, Rochette A, Bravo G, Bourget A. Participation after stroke compared to normal aging. J Rehabil Med. 2005; 37:353–357. PMID: 16287666.

18. Jette AM, Keysor J, Coster W, Ni P, Haley S. Beyond function: predicting participation in a rehabilitation cohort. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005; 86:2087–2094. PMID: 16271553.

19. Kim SH, Byeon YC, Sohn CG, Lee YH, Lee MK, Lee SH, et al. 2011 Survey of the Disabled. Korea Institute for Health and Social affiars.

20. Rimmer JH, Wang E, Smith D. Barriers associated with exercise and community access for individuals with stroke. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2008; 45:315–322. PMID: 18566948.

21. Shaughnessy M, Resnick BM, Macko RF. Testing a model of post-stroke exercise behavior. Rehabil Nurs. 2006; 31:15–21. PMID: 16422040.

22. Hansen AP, Marcussen NS, Klit H, Andersen G, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. Pain following stroke: a prospective study. Eur J Pain. 2012; 16:1128–1136. PMID: 22407963.

23. Jonsson AC, Lindgren I, Hallstrom B, Norrving B, Lindgren A. Prevalence and intensity of pain after stroke: a population based study focusing on patients' perspectives. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006; 77:590–595. PMID: 16354737.

24. Kim BS. Development of medical rehabilitation system for persons with disabilities. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2004; 28:1–6.

Table 2

Reports of leisure activities or activity categories performed before and/or after stroke for participants

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download