Abstract

Persistent enterocutaneous fistula after the removal of a gastrostomy tube is an unusual complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). The following case report describes an 81-year-old man diagnosed with stroke and dysphagia in May 2008. The patient had been using a PEG since 2008, and PEG site infection occurred in June 2013. The PEG tube was removed and a new PEG tube was inserted. Thereafter, formation of gastrocutaneous fistula around the previous infected PEG site was observed. The fistula was refractory to medical management, accompanied by long duration of fasting and peripheral alimentation. Therefore, gastrojejunostomy tube insertion via the previously inserted PEG tube was performed, under fluoroscopic guidance; this mode of management was successful. For patients who have a gastrocutaneous fistula, gastrojejunostomy tube insertion via the pre-existing PEG tube is a safe and effective alternative management for enteral feeding.

Since 1980s, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) has been the preferred method of long-term enteral feeding [1]. In Korea, after PEG was first introduced in 1986 by Choi et al. [2], PEG feeding has been widely used for patients who cannot be fed via the oral route.

Jejunal feeding is preferred to gastric feeding in patients with functional or structural gastric defects and normal small bowel function. Jejunal access using a jejunal tube through a PEG was first described by Ponsky [3] in 1984. Radiologic conversion of a gastrostomy to a gastrojejunostomy involves insertion of a gastrojejunostomy tube through the pre-existing tract under fluoroscopic guidance [4].

Persistent gastrocutaneous fistula after the removal of a PEG is an unusual complication. The fistulous tract usually closes spontaneously within 1-14 days [5,6]. Conservative treatments include parenteral therapy, reduction of the acidic pH of the stomach, and pharmacological acceleration of gastric emptying [6,7], and surgical therapy is generally reserved for patients refractory to these measures. Some patients are managed with endoscopic clips and fibrin glues [8]. We present the case of a patient who developed a persistent gastrocutaneous fistula after PEG removal and was treated with gastrojejunostomy tube insertion via a PEG (jejunal extension of a PEG) under fluoroscopic guidance for enteral nutrition.

In May 2008, an 81-year-old man was transferred to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at our institute, after hematoma evacuation and a ventriculoperitoneal shunt operation for left thalamic hemorrhage, intraventricular hemorrhage, and hydrocephalus. He was previously diagnosed with dysphagia and had undergone PEG. When he was transferred to our hospital, he was still receiving nutritional support through the PEG, without any complications.

The first PEG site infection occurred in September 2009. The PEG tube was removed, and a new PEG tube was inserted at another site. He then received enteral feeding through the PEG for 4 years. His body weight was maintained at an appropriate level of 70 kg.

In June 2013, the patient stopped responding to verbal commands, but his cognition was intact, and he responded to pain. He could not roll over in bed, or sit up. In addition, new signs of infection were observed around the PEG insertion site. A round swelling and erythematous skin changes with pus-like discharge were seen (Fig. 1A). On enhanced abdominal CT, inflammation around the PEG tube was observed (Fig. 1B). When leukocytosis and increased levels of serum C-reactive protein (CRP) were confirmed, he was started on intravenous antibiotic therapy. The PEG tube had to be removed; hence, the patient was kept fasting, with peripheral nutritional support. One month after the PEG removal, the complications at the PEG site seemed to have resolved (Fig. 2). The leukocytosis resolved and serum CRP levels normalized, but the patient lost about 3 kg of body weight. A new PEG tube was inserted 2 cm above the previous PEG site (Fig. 3). When he was started on enteral feeding through the new PEG, leakage of gastric contents was observed. The leakage was from the second PEG site. On enhanced abdominal CT, there was a gastrocutaneous fistula around the second PEG insertion site (Fig. 4). As spontaneous fistula closure did not occur in spite of medical management for one month, the patient received simple suturing of the fistula and was kept fasting. After 2 weeks, the fistula was not closed. Surgical treatment under general anesthesia was too risky. Endoscopic intervention using hemoclips and fibrin glues was under consideration. However, the patient had already endured a very long duration of fasting, while waiting for the fistula to heal. He needed to be started on enteral feeding as soon as possible, and fistula closure was second to that. Also, additional endoscopic intervention could burden the patient considering his exhausted state. Instead, he could be started on enteral feeding if the tip of the feeding tube is placed more distally than the stomach, regardless of the fistula closure.

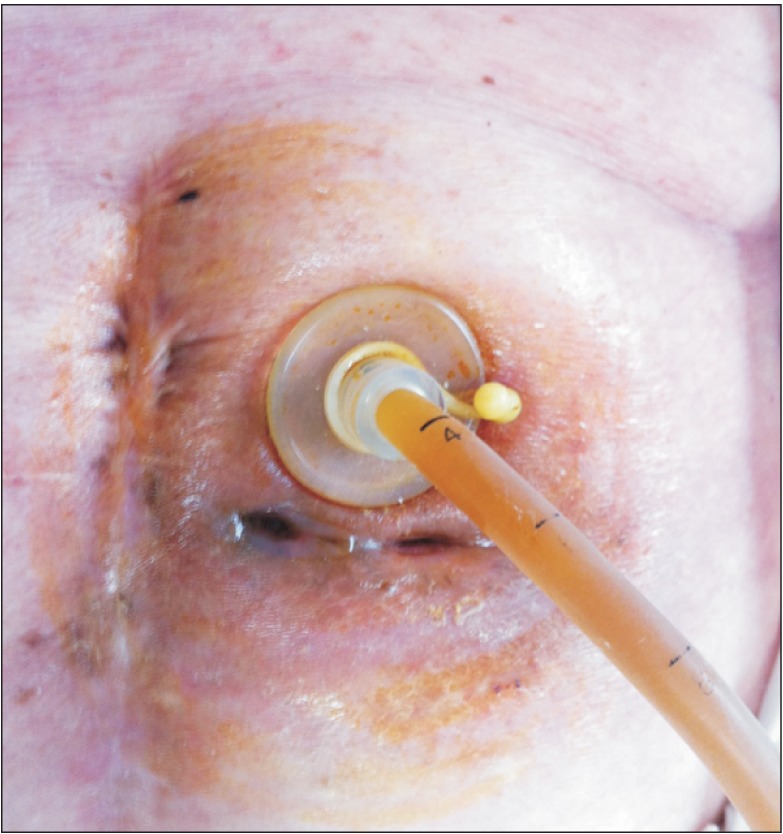

A gastrojejunostomy tube was inserted via the newly inserted PEG tube under fluoroscopic guidance. This procedure was performed on August 27, 2013, 3 months after the PEG site infection. A guide wire and a gastrojejunostomy catheter were inserted into the third PEG tube. Through fluoroscopy, the radiologist confirmed that the tip of the catheter had reached the jejunum (Fig. 5A). The patient was started on enteral feeding through the gastrojejunostomy without any significant complications (Fig. 5B).

About 8% of stroke patients need PEG due to dysphagia and 29% of stroke patients who use a PEG recover from dysphagia, and then the PEG is removed within 8 months in most cases [1,9]. The PEG is a safe and convenient tool for enteral feeding, but complications such as gastrocutaneous fistula formation develop occasionally. Spontaneous closure of the gastrocutaneous fistula is mostly influenced by the duration of PEG insertion and not by PEG properties, insertion site complications, and coexisting medical conditions. Only 10% of the patients who have their tube removed within 8 months of insertion have a persistent fistula, whereas 92% of the patients who have their tube removed after 8 months have a persistent fistula [10]. For fistula formation, the skin and gastric mucosa need to grow and undergo epithelialization over the PEG site; hence, this process takes a long time.

In this case too, the patient underwent removal of the PEG twice, and site infections were observed at both instances. The first time, after 14 months of PEG use, the fistula healed spontaneously, but after removal of the second PEG after 4 years of use, the fistula failed to close spontaneously; the difference between the two events was the PEG maintenance period.

Currently, the number of long-term survivors after stroke is increasing, and consequently, the number of elderly patients using a PEG is increasing. A fistula formed after removal of a PEG used for a long duration is less likely to respond to medical therapy. In addition, in elderly stroke patients, surgical approaches could be risky, especially when general anesthesia is required. Recently, endoscopic intervention using clips and fibrin glues has shown optimistic results in treatment of fistula.

Fistula closure is essential for patients who receive nutrition through the stomach, including oral diet, PEG and nasogastric tube diet because gastric contents can leak out through the open fistula. However, when the tip of the feeding tube is inserted distally than the fistula, enteral feeding through the tube can be performed regardless of the fistula closure.

In the aforementioned cases, gastrojejunostomy insertion via the PEG is a safe and easy alternative. There are 29 case reports with high success rates of gastrojejunostomy insertion via a PEG, under fluoroscopic guidance [4]. After gastrojejunostomy insertion, the most common complication is dislocation of the catheter which is easily manageable [4].

In summary, when a patient cannot receive nutrition through the oral route and has a refractory gastrocutaneous fistula after PEG removal, gastrojejunostomy is a good alternative nutrition route. In addition, it can help to rest the stomach and probably promote fistula healing.

References

1. James A, Kapur K, Hawthorne AB. Long-term outcome of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding in patients with dysphagic stroke. Age Ageing. 1998; 27:671–676. PMID: 10408659.

2. Choi IT, Chae SI, Song JH, Kim YJ, Nah YH. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Korean J Gastroenterol. 1986; 18:77–83.

3. Ponsky JL. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and jejunostomy: endoscopic highlights. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984; 30:306–307. PMID: 6489716.

4. Shin KH, Shin JH, Song HY, Yang ZQ, Kim JH, Kim KR. Primary and conversion percutaneous gastrojejunostomy under fluoroscopic guidance: 10 years of experience. Clin Imaging. 2008; 32:274–279. PMID: 18603182.

5. Peter S, Geyer M, Beglinger C. Persistent gastrocutaneous fistula after percutaneous gastrostomy tube removal. Endoscopy. 2006; 38:539–540. PMID: 16767596.

6. Makris J, Sheiman RG. Percutaneous treatment of a gastrocutaneous fistula after gastrostomy tube removal. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002; 13(2 Pt 1):205–207. PMID: 11830628.

7. El-Rifai N, Michaud L, Mention K, Guimber D, Caldari D, Turck D, et al. Persistence of gastrocutaneous fistula after removal of gastrostomy tubes in children: prevalence and associated factors. Endoscopy. 2004; 36:700–704. PMID: 15280975.

8. Akhras J, Tobi M, Zagnoon A. Endoscopic fibrin sealant injection with application of hemostatic clips: a novel method of closing a refractory gastrocutaneous fistula. Dig Dis Sci. 2005; 50:1872–1874. PMID: 16187189.

9. Akpunonu BE, Mutgi AB, Roberts C, Khuder SA, Federman DJ, Lee L. Modified barium swallow does not affect how often PEGs are placed after stroke. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997; 24:74–78. PMID: 9077720.

10. Janik TA, Hendrickson RJ, Janik JS, Landholm AE. Analysis of factors affecting the spontaneous closure of a gastrocutaneous fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 2004; 39:1197–1199. PMID: 15300526.

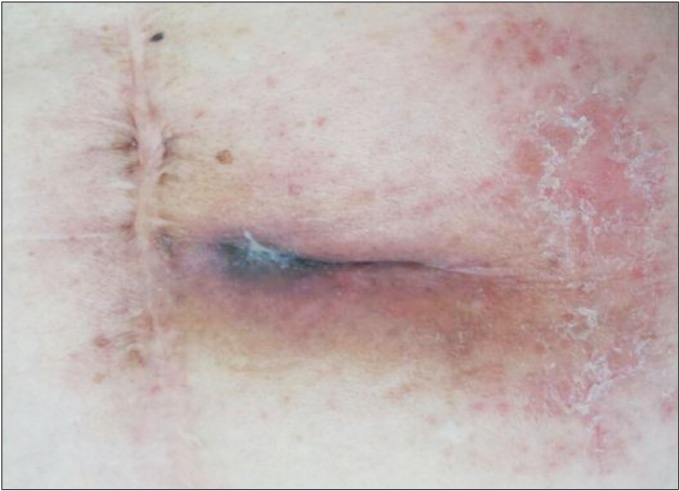

Fig. 1

(A) A round swelling around the percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) and (B) enhancing soft tissue infiltration around the PEG site; subcutaneous layer (arrow) without peritonitis; abscess formation.

Fig. 2

One month after removal of the complicated percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, the skin appears to have healed.

Fig. 3

A new percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) is inserted 2 cm above the site of the previous PEG insertion.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download