Abstract

Groin pain in athletes is a complex diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. Sports hernia is one of the common causes of groin pain. We report a case of sports hernia, initially presented as groin pain and aggravated by sports activity. A 19-year-old soccer player visited the outpatient department of general surgery and was referred to the rehabilitation center due to no abnormalities detected in the abdomen and pelvis by computed tomography. An incipient direct bulge of the posterior inguinal wall was detected with dynamic ultrasound when abdominal tension was induced by raising both legs during a full inhalation. Surgery was performed and preoperatively both groins showed the presence of inguinal hernia. Diagnosing sports hernia is very challenging. Through careful history documentation and physical examination followed by dynamic ultrasonography, we identified his posterior inguinal wall deficiency for early management.

Groin sports-related injury rates range from 0.5% to 6.2% [1]. Typically occurring in young athletic males, sports hernias usually present with insidious onset of exercise-related groin pain [2]. Patients usually report pain in the groin (dull, diffuse, sharp, and burning), often with radiation down the inner thigh, the scrotum and the pubic bone [3]. The pain improves with rest, however, returns upon patient participating in sports activities, especially kicking, sudden changes in movement, coughing, and other Valsalva-type maneuvers [34]. Diagnosis of sports hernia is achieved through a careful history documentation, physical examination, and several imaging modalities [3].

Every patient should be analyzed with a dynamic ultrasound scan in a supine position using a high-frequency transducer [34]. Sports hernia is diagnosed if a convex anterior bulge of the posterior inguinal wall is observed during stress [34].

Using dynamic investigation, we also found the patient's posterior inguinal wall deficiency, which was not detected by both computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Early detection and initiation of the correct treatment is essential in sports hernia management [2].

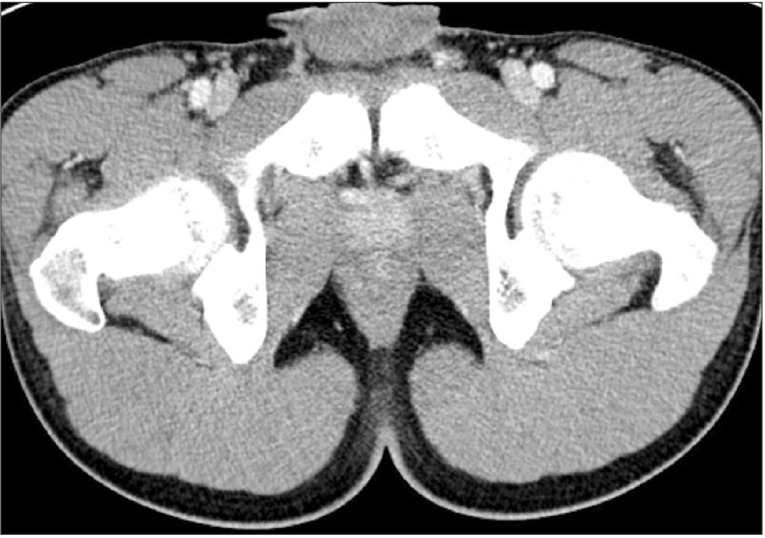

A 19-year-old man was referred from general surgery. He was a soccer player and had been playing for several years. He had experienced insidious dull and diffuse pain in his left groin area, which was aggravated during sports activity for a month. The subject assumed his pain originated from an inguinal hernia and went to a surgeon first. However, his abdomen and pelvis CT showed normal posterior inguinal wall contours without any other abnormalities (Fig. 1). A professional radiologist performed an ultrasonography; however, no significant findings were detected. Thinking it was unrelated to hernia, the surgeon referred him to the rehabilitation center.

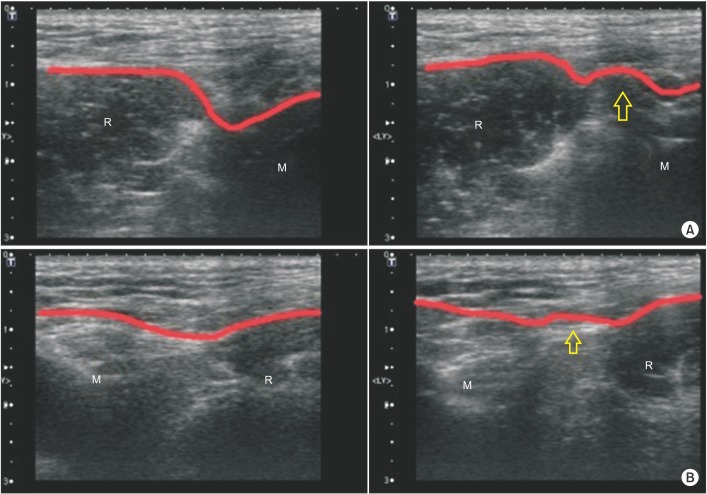

We carried out a detailed physical examination. The insidious onset, gradual worsening with activity and diffuse nature of the groin pain proposed non-traumatic pathology. We asked the patient to identify the areas of pain by shading them on a pain diagram (Fig. 2). On inspection of both groins, there was no definite swelling or sign of injury on either side. Scrotum was normal in size and looked symmetrical. With the patient lying supine, we let him raise his both legs gradually to make an eccentric contraction of the lower abdominal muscles. This action produced unbearable pain to the subject.

For further evaluation, we performed an ultrasonography examination. Having the patient lying in supine position, we used a 5-MHz high-frequency transducer and explored both sides of groin and scrotal region. During the initial investigation with the patient in a recumbent position, we failed to find any evidence of pathology; however, we found significant clues through dynamic investigation. We detected an incipient direct bulge of the posterior inguinal wall after the patient contracted his abdominal muscles by raising both his legs to about 30° and fully inhaling (Fig. 3). Incipient direct bulges of the posterior inguinal wall were detected on both sides of the groin, more prominently on the left.

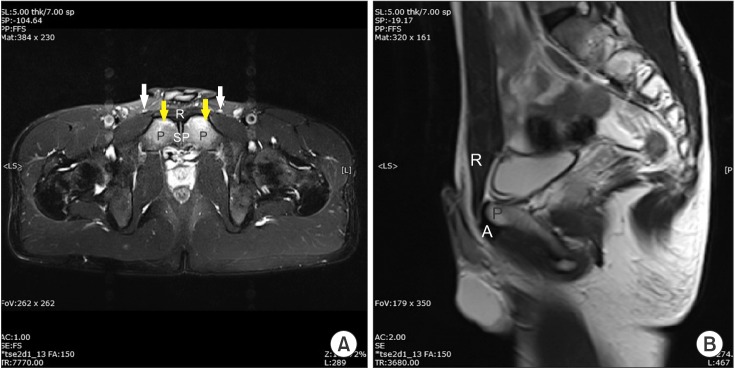

To rule out other possible lesions, we prescribed an MRI of the pelvic region. It identified a bilateral bone marrow edema and enhancement of both symphysis pubes, favoring osteitis pubis rather than a simple sports hernia (Fig. 4).

Based on the dynamic ultrasonographic findings, we referred the subject to a general surgeon for a posterior inguinal wall deficiency reconstruction operation. Preoperatively both groins did show the presence of an inguinal hernia; a direct type on left side and both a direct and indirect form on right without a prominent fascia tear. Using the totally extraperitoneal (TEP) repair technique, a reduction of both hernias followed by Prolene mesh placement on each side to seal the hernia from outside the peritoneum was performed.

The postoperative outcome was uneventful and the patient was discharged four days after surgery. Before discharge, he was educated in exercises including curl-ups, side-bridge, bird-dog, and more to perform on his own at home to prevent possible related diseases like rectus abdominis or adductor longus tendinopathy. At the one week follow-up visit, he expressed mild persistent pain on both groins during the resisted straight leg raise (SLR) test, however, it did not bother him as much as before. He returned to field one month after the operation with substantial symptom improvement. Three months after surgery the subject was completely symptom-free, even when engaged in sports activities with no residual pain noted during the resisted SLR test.

Acute or chronic groin pain is not uncommon in athletes and has a long list of differential diagnoses, including muscle strain, adductor tendinitis, osteitis pubis, sports hernia, varicocele, and testicular torsion [5]. Sports hernia should be high on the list of differential diagnoses in groin pain [6]. The symptoms of sports hernia are consistent and patients will usually present with a combination of vague unilateral or bilateral groin pain. Pain occurs on exertion, in particular sprinting, cutting or twisting, sidestepping, kicking, or sitting up [2].

Early detection and initiation of the correct treatment is essential to manage sports hernias [2]. In our case, the initial surgeon was not familiar with sports hernias and the radiologist did not perform a dynamic ultrasonographic examination. This neglect caused the time from the patient's initial visit to hernia repair to take a month's time, which is a long time for this injury to linger. An inguinal or femoral hernia is relatively uncommon in young people [7]. Since the patient was a soccer player, the possibility of sports hernia should have been considered.

The two main imaging modalities used to assist in the diagnosis of sports hernia are MRI and ultrasound [2]. MRI is reported to have good diagnostic potential; however, the examination is done with the patient in the recumbent position [2]. This explains the high rate of false-negative results with MRI and supports dynamic ultrasound scanning as a diagnostically conclusive option, only if performed by an experienced examiner [24]. In our case, the MRI findings favored osteitis pubis rather than sports hernia and bone marrow edema visualized by MRI. These are unusual findings among soccer players [8]. Further, the dynamic ultrasonographic results strongly supported the presence of a sports hernia. With our analyses, we persuaded the surgeon to carry out the operation, which finally discovered hernias on both groins and resolved patient's long-standing pain.

The importance of dynamic investigation is emphasized in previous studies. According to Orchard et al. [4], 'ballooning' of the inguinal canal alone should not be regarded as a diagnostic tool for inguinal hernia, as it can also be caused by varicocele or lipoma of the cord. Therefore, anterior displacement and a progressive convex anterior bulge of the posterior inguinal wall under stress are important features that serve to increase the specificity of a positive report of sports hernia.

References

2. Brown A, Abrahams S, Remedios D, Chadwick SJ. Sports hernia: a clinical update. Br J Gen Pract. 2013; 63:e235–e237. PMID: 23561792.

3. Muschaweck U, Berger LM. Sportsmen's groin-diagnostic approach and treatment with the minimal repair technique: a single-center uncontrolled clinical review. Sports Health. 2010; 2:216–221. PMID: 23015941.

4. Orchard JW, Read JW, Neophyton J, Garlick D. Groin pain associated with ultrasound finding of inguinal canal posterior wall deficiency in Australian Rules footballers. Br J Sports Med. 1998; 32:134–139. PMID: 9631220.

5. Jain M, Tantia O, Sasmal P, Khanna S, Sen B. Chronic groin pain in athletes: sportsman's hernia with bilateral femoral hernia. Indian J Surg. 2010; 72:343–346. PMID: 21938201.

6. Hackney RG. The sports hernia: a cause of chronic groin pain. Br J Sports Med. 1993; 27:58–62. PMID: 8457816.

7. Woodward JS, Parker A, Macdonald RM. Non-surgical treatment of a professional hockey player with the signs and symptoms of sports hernia: a case report. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012; 7:85–100. PMID: 22319682.

8. Verrall GM, Slavotinek JP, Fon GT. Incidence of pubic bone marrow oedema in Australian rules football players: relation to groin pain. Br J Sports Med. 2001; 35:28–33. PMID: 11157458.

Fig. 1

Axial view of the post-contrast abdomen and pelvis computed tomography at symphysis pubis level demonstrating no evidence of hernia.

Fig. 3

Short axis view of both sides of the posterior inguinal wall (A, left side; B, right side) with patient resting (left) and straining (right). When patient straining, incipient direct bulge of the posterior inguinal wall is seen, more prominent on left side. The superimposed red line indicates the posterior inguinal wall. It is initially concave when patient is at rest, but displaced anteriorly as a convex bulge (demonstrated with yellow arrow) on straining. Rectus abdominis (R) and lateral abdominal muscles (M) are indicated.

Fig. 4

(A) Axial and (B) obliquecoronal fat-saturated T2 images of the pelvic bone. Magnetic resonance imaging showing bilateral symmetric bone marrow edema (yellow arrow) and enhancement in both symphysis pubis (SP), more prominent in anteroinferior aspect. Note no abnormal findings in muscle and aponeurosis of both rectus abdominis (R) and adductor longus (A) around pubic bone (P). Spermatic cord (S) is also normal in place.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download