INTRODUCTION

Sjögren syndrome is a chronic autoimmune disease that involves exocrine glands. The disease is known to involve the peripheral nervous system in roughly 10%-20% of cases, and the central nervous system in 8% of reported cases [

1]. No cases have been reported in South Korea where primary Sjögren syndrome involved the sensory afferent pathway and caused systemic central neuropathic pain [

2,

3]. Intractable pain is defined as extreme pain lasting over three months that does not respond to drug treatment, physical therapy, nerve block, or other conventional treatment methods. The bouts of pain are often accompanied by limitations in the patient's daily living patterns, such as sleep impairment and depression [

4]. The first-line medications recommended for neuropathic pain includes tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and calcium channel α

2-δ ligands. Typically recommended second-line medications include opioid analgesics, and third-line medication includes carbamazepine, valproic acid, bupropion, or citalopram; combination therapies are also considered for treatment [

5]. The authors have direct involvement with a case where combination drug therapy led to noticeable improvement of intractable pain in a patient with Sjögren syndrome involving the central nervous system. We present this case report along with a brief literature review.

Go to :

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old female patient was admitted to the neurological department of our hospital for muscle weakness in the left-side limbs, and pain in the upper left limb, and both lower limbs, that started seven days before the hospital visit. Her medical records indicated that she had taken drugs for high blood pressure and diabetes for 4 years; she had started receiving ongoing conservative treatment for right-side lumbosacral radiculopathy 3 years ago. Over the past several years, the patient experienced symptoms of dryness in the eyes and mouth. Due to dryness in the eyes, the patient needed to apply artificial tears occasionally. Parotid glands on either side were not swollen. The patient had difficulty swallowing food if the meal did not come with soup. There were no symptoms of arthralgia, Raynaud phenomenon, or lymphadenopathy. There was no record of receiving treatment for lung involvement. In the five days prior to admission, the patient had experienced voiding difficulty and constipation.

At the time of admission, the patient's blood pressure was 170/90 mmHg, all other vital signs were normal. The physical examination showed decreased vibration sensitivity and piercing pain in the left side C4-T2 level dermatome of 7 points on the numeric rating scale (NRS). She also complained of burning pain of NRS 6 points in the right side L5-S1 level dermatome and showed reduced vibration sensitivity, proprioception, and NRS 7 point tingling pain and allodynia in the left-side L3 level dermatome and below. A manual muscle test showed normal muscle strength of 5/5 in the right-side limbs, reduced muscle strength 4/5 in the left-side flexors and extensors of the shoulder, elbow, wrist, hip, and knee joints; there was also reduced muscle strength 3/5 in the left-side ankle dorsiflexor and ankle plantar flexor. Left-side ankle and knee jerk reflexes were decreased. Neither a Babinski reflex or ankle clonus was observed on either side.

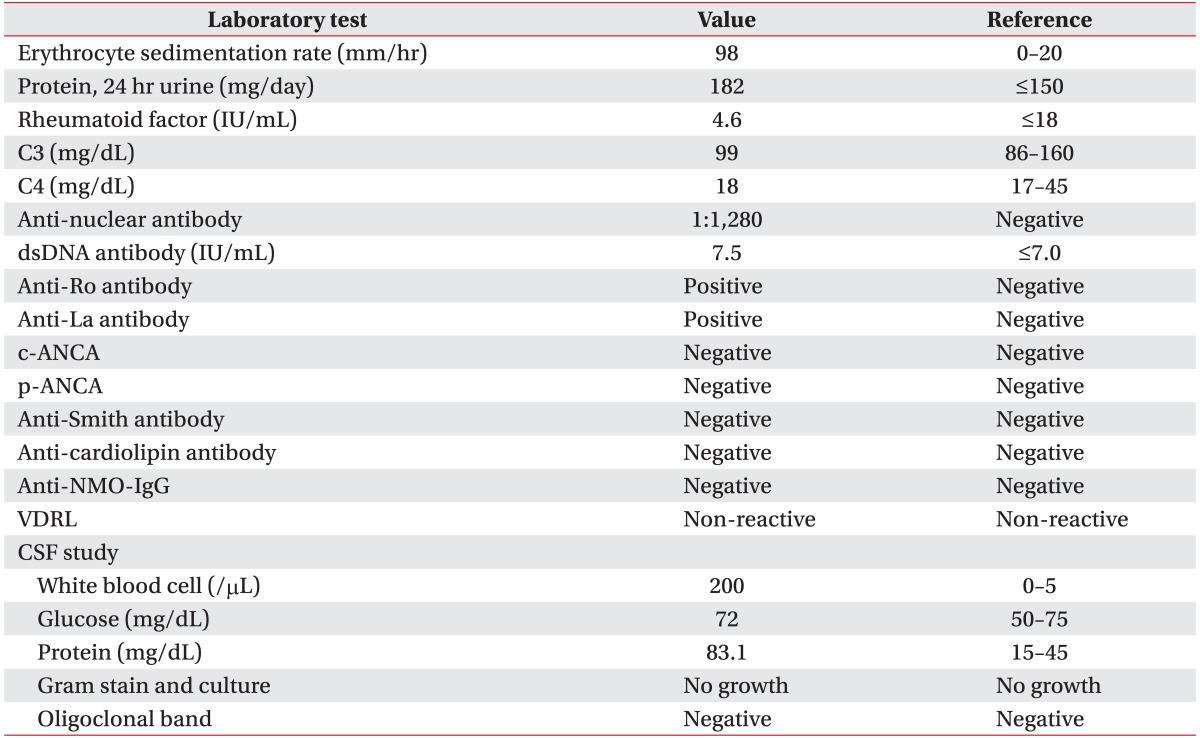

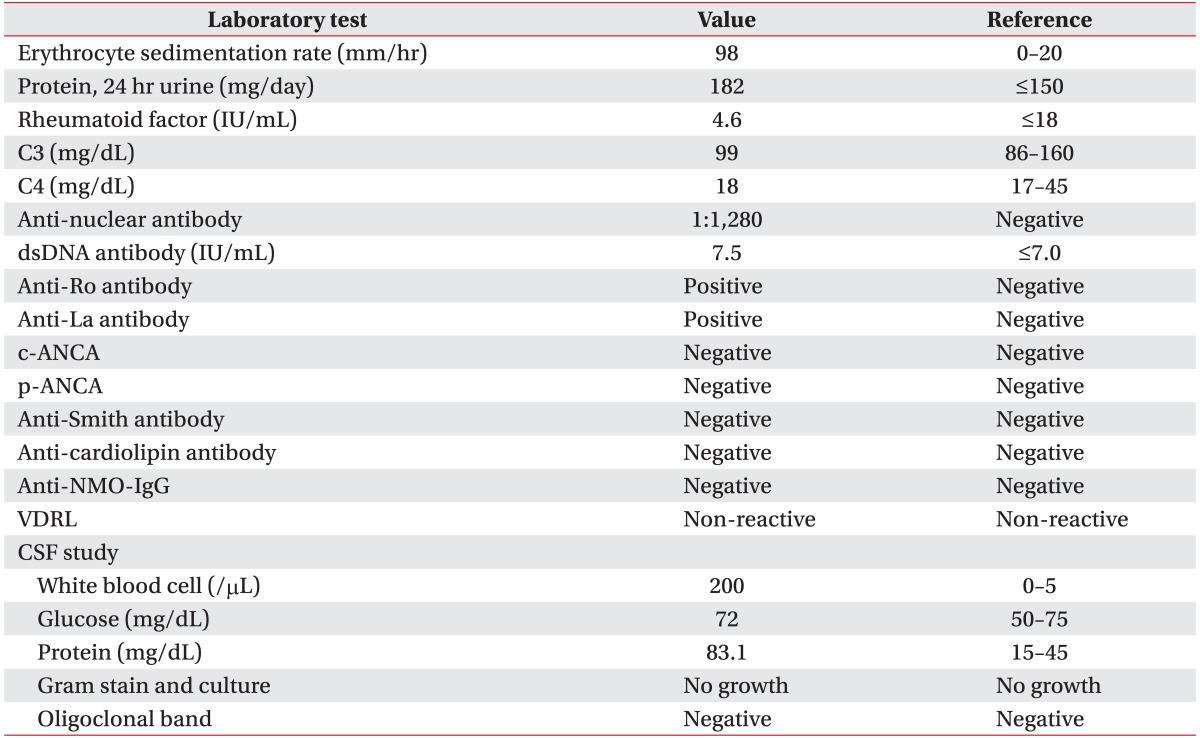

In the laboratory evaluation, serum was positive for anti-Ro and anti-La antibodies, and negative for anti-NMO-IgG. In the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination, the oligoclonal band was negative, and bacteria and virus culture tests were all negative (

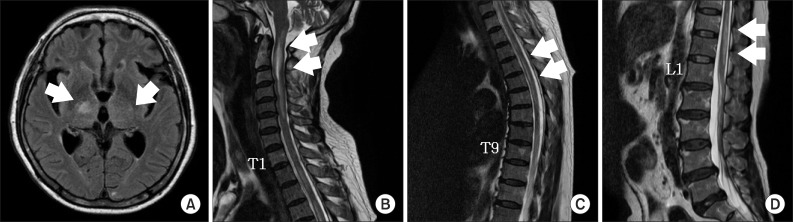

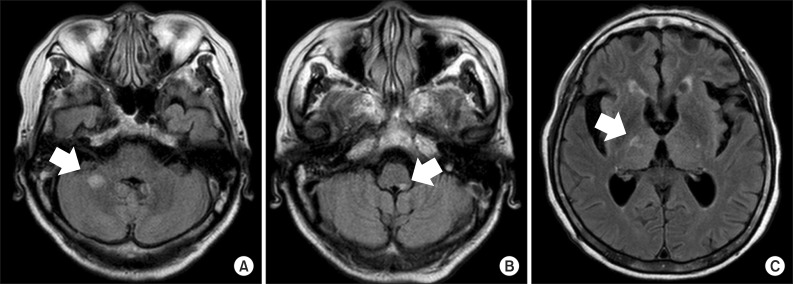

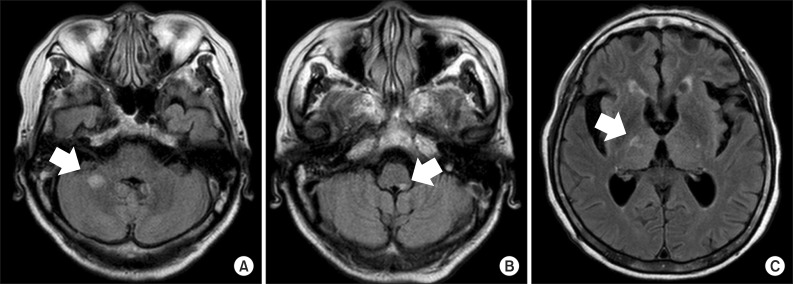

Table 1). Schirmer test showed a normal evaluation, and a minor salivary gland biopsy revealed infiltration of lymphocytes. T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed at admission showed non-enhancing ill-defined lesions with high signal intensity in the right thalamus and posterior limb of the internal capsule, on both sides. Additionally, spinal cord MRI T2-weighted images showed multifocal contrast-enhancing ill-defined intramedullary lesions and swelling of the spinal cord from cervical to lumbar regions (

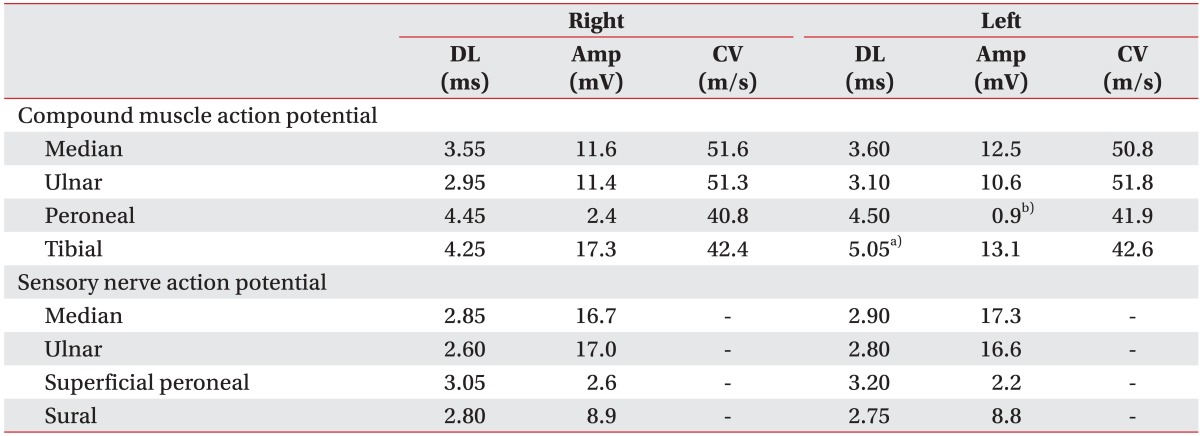

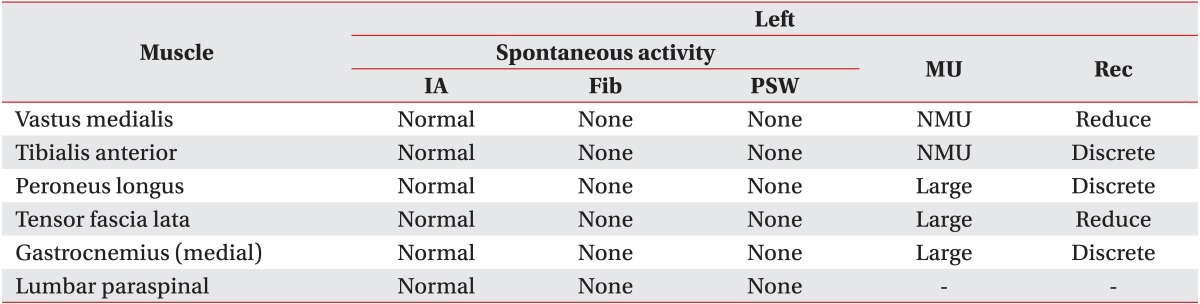

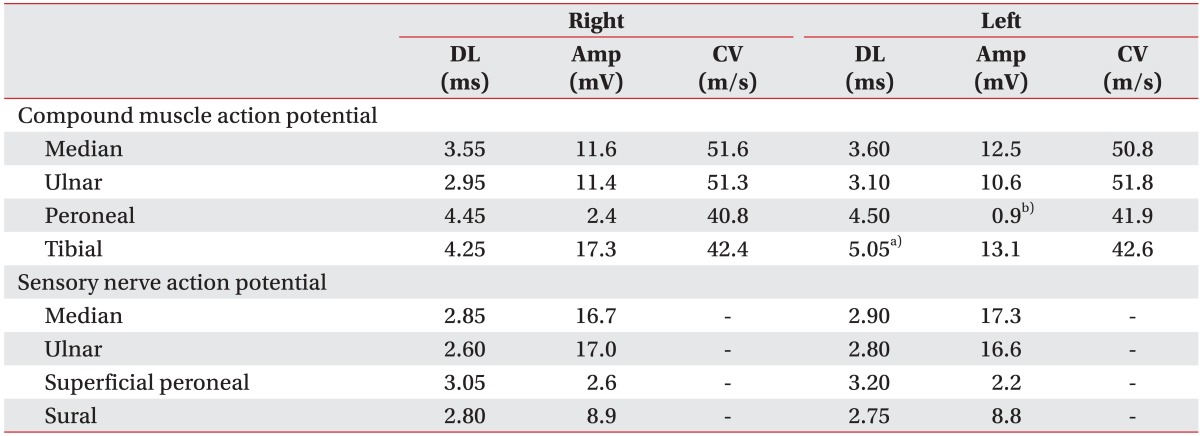

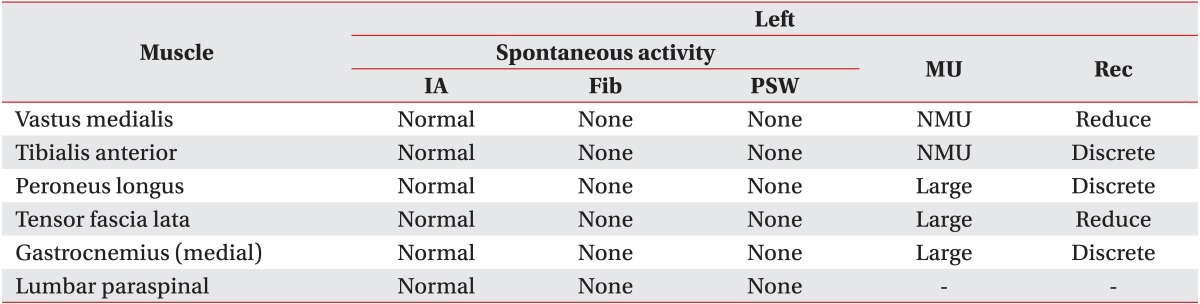

Fig. 1). Electromyography showed left-side L5-S1 radiculopathy of the old lesions. There were no other peripheral neuropathies observed (

Tables 2,

3).

| Fig. 1Magnetic resonance images of the brain and spinal cord. (A) T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery axial imaging demonstrated a non-enhancing ill-defined high intensity signal involving the posterior limb of the both internal capsule and right thalamus (arrow). (B-D) T2-weighted sagittal imaging demonstrated multifocal intramedullary ill-defined contrast-enhancing lesion with cord swelling from the C-spine to the L-spine (arrows).

|

Table 1

Laboratory test results of case

Table 2

Results of nerve conduction study

Table 3

Results of needle electromyography

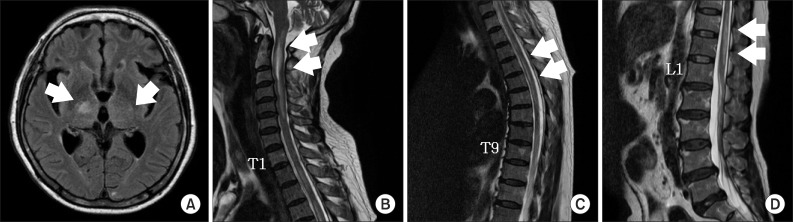

The patient received intravenous injections of methylprednisolone sodium succinate (1,000 mg/day) for 5 days, and after that, human immunoglobulin (21,000 mg/day) for 5 days, followed by oral prednisolone (30 mg/day). To address the neuropathic pain after admission, amitriptyline (5 mg/two times a day) was administered. However, due to anticholinergic effects, this was changed to gabapentin (100 mg/three times a day) with an increased dose, but the neuropathic pain of the patient did not attenuate from 7 on the NRS. Due to sleep impairment, depression, and suicidal ideation, the patient received treatment at the hospital's department of psychiatry. Even after intravenous injections of methyl-prednisolone and immunoglobulin, a manual muscle test showed that the muscle strength in left-side flexors and extensors of shoulder, elbow, wrist, hip and knee joints, and ankle dorsiflexor and ankle plantar flexor were exacerbated, down to 0/5. Oral steroid treatment was maintained, and approximately 1 month after admission, left-side flexors and extensors of the shoulder joint, and left-side flexors and extensors of the elbow and wrist joints, improved to 2/5 and 3/5, respectively. Also, left-side flexors of the hip joint and extensors of the knee joint improved to 2/5 and left-side extensors of hip joint, flexors of knee joint, ankle dorsiflexor and ankle plantar flexor improved to 1/5. At that point, the patient's range of pain expanded to the neck, waist, and both limbs, and reached 7 points on the NRS dozens of times a day, lasting for approximately 1-2 minutes, and appearing in the form of a tightening pain. In particular, the patient frequently complained of pain during rehabilitation treatment, which decreased motivation and compliance. Gabapentin was increased to a dose of 600 mg/three times a day and a hot pack, radiant heat, ultrasound, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation treatment to the painful area were additionally applied. However, approximately 2 months after admission, the patient's neuropathic pain worsened to 9 points on the NRS. Gabapentin was increased to the maximum dosage (1,200 mg/three times a day), and venlafaxine (56.25 mg/orally at bedtime) was administered. However, this did not result in satisfactory regulation of the pain, which remained at the level of 7 points on the NRS. Two weeks after increasing gabapentin to the maximum dosage and starting to administer venlafaxine, the patient was additionally administered carbamazepine (200 mg/two times a day), a third-line medication. One week after starting the administration of carbamazepine, the patient's intractable pain showed a noticeable improvement, reducing to 1 point on the NRS. There was no significant difference in the patient's muscle strength after the pain became worse approximately 1 month after admission. Approximately 3 months after admission, dysarthria occurred during rehabilitation treatment and MRI was performed. MR T2-FLAIR imaging demonstrated new lesions with high signal intensity in the right middle cerebellar peduncle and left side of the medulla. The lesions involving the posterior limbs of the internal capsule decreased in size compared to previous imaging (

Fig. 2). The patient was again transferred to the neurological department and administered an increased dosage of oral prednisolone. Even after the transfer to the neurological department, the patient's pain remained at 1 on the NRS, and muscle strength remained stable. The patient was transferred to another rehabilitation hospital.

| Fig. 2Magnetic resonance images of the brain. (A, B) T2 fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) axial imaging demonstrated a newly-appeared nodular high intensity signal involving the right middle cerebellar peduncle and left side of medulla (arrows). (C) T2 FLAIR axial imaging demonstrated a decreased size and less prominent patchy intensity signal involving the posterior limb of the right internal capsule (arrow).

|

Three months after referral to another rehabilitation hospital, there was a slight improvement in muscle strength of the left-side hip joint extensors to 2/5, and left-side knee joint extensors to 3/5. There was no significant change in the strength of other muscles. The patient could stand at the parallel bar with the help of a physical therapist. The patient's pain had no significant changes and remained at 1 point on the NRS, the types and amount of administered medication were maintained.

Go to :

DISCUSSION

The diagnosis of primary Sjögren syndrome in this case report was based on the revised version of the European criteria of the American-European Consensus Group that consists of 6 items [

6]. In the case of this patient, histological findings and an autoantibody test were positive; symptoms of eye dryness and mouth dryness were also present. With the patient meeting four items of the 6-item criteria, we could formally diagnose the patient with Sjögren syndrome. Therefore, Rose bengal staining, unstimulated whole salivary flow, parotid sialography, and salivary scintigraphy tests were not performed on the case. Because there was no history of past head or neck radiation treatment, hepatitis C infection, acquired immunodeficiency disease, pre-existing lymphoma, sarcoidosis, graft versus host disease, or the use of anticholinergic drugs, the patient was diagnosed with primary Sjögren syndrome [

6]. The central nervous system involvement in Sjögren syndrome and multiple sclerosis have many common characteristics: multifocal lesions, relapse, and improvement progression. Indeed, MRI findings in 40% of the patients with Sjögren syndrome demonstrate consistency with multiple sclerosis [

7]. In our case as well, there were MRI findings consistent with those found in multiple sclerosis; however, the CSF test for the oligoclonal band specific to multiple sclerosis was negative [

7]. The oligoclonal band became the important differentiation diagnostic point, and based on past medical history, histological evaluation, and the autoantibody test, the patient was diagnosed with Sjögren syndrome rather than multiple sclerosis. Systemic lupus erythematosus was also excluded as the patient demonstrated positive findings only in the anti-nuclear and anti-dsDNA antibody tests. Multiple cerebral infarction and vasculitis were excluded at the time of admission because magnetic resonance angiography demonstrated no strictures or closure of blood vessels in the brain. Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) was also excluded because the patient exhibited no symptoms of vision impairment, and the anti-NMO-IgG test was negative. It was possible to exclude transverse myelitis, as virus and bacteria cultures of CSF and serum were all negative.

According to extant clinical studies, observing the patients' prognosis for an average of 7 years demonstrated that 26 out of 82 patients diagnosed with primary Sjögren syndrome had a recurrence of neurological lesions [

7]. Additionally, 52% of the patients could not lead an independent life, while 78% of these patients had lesions of the central nervous system [

7]. Twenty-nine of 73 patients who received corticosteroid treatment demonstrated neurological improvement and stabilization [

7]. In the case of this patient, brain lesions recurred approximately 3 months after hospital admission, and independent living was impossible, but the increase of oral prednisolone, alone, led to comparative neurological stability, which is consistent with previous studies.

Primary Sjögren syndrome mainly involves the peripheral nervous system; it was necessary in this case to confirm peripheral neuropathy [

7]. Because the patient had a clinical history of diabetes and lumbar neuropathy, it was also necessary to differentiate the impact from Sjögren disease from the deterioration due to underlying diseases. Left-side disk herniation was observed on the MRI of the patient's lumbar and sacral vertebrae conducted 3 years ago. However, the MRI of lumbar and sacral vertebrae made at the time of admission revealed no deterioration. Electromyography demonstrated radiculopathy in the L5-S1 region, but there were no other peripheral neuropathies discovered. The left-side sensation symptoms of the patient were new symptoms, comorbid with Sjögren syndrome; however, its correlation with left-side lumbosacral radiculopathy was ruled out.

According to results of previous studies, TCAs were found to be effective in treating post-infarction central neuropathic pain, and calcium channel α

2-δ ligands were found to be effective for treating central neuropathic pain following spinal cord damage [

8]. In this reported case, amitriptyline of the TCA drug class was initially administered, and later changed to gabapentin due to the former's anticholinergic effects; this treatment, however, did not lead to a satisfactory amelioration of the pain. It proved difficult to administer opioid drugs that are second-line medication to the patient due to the related side effects of constipation and urinary retention. In addition, invasive intervention procedures, such as nerve block and spinal cord stimulation, were considered too difficult considering the patient's age-associated deteriorated physical state. In cases where it is difficult to manage neuropathic pain with one type of medication, combination therapy may be considered. Synergistic effects of the different drug components can be expected and compared to a single drug administration therapeutic modality, it is possible to attain analgesic effects with lower dosages, which can also decrease their side effects [

5]. However, a decision about combining medications is also an intuitive one, and most of the related studies in the literature are studies on peripheral, not central, neuropathic pain [

9,

10]. In the case of this patient, satisfactory pain management could be obtained when carbamazepine was administered along with gabapentin and venlafaxine. No side effects were observed.

Regarding the limitations of this case report, it should be pointed out that we should have tapered the use of gabapentin and venlafaxine to verify that carbamazepine had the greatest effect in managing pain; however, we could not implement this procedure due to patient objections for fear of extreme, chronic pain experienced in the past. Furthermore, according to previous clinical studies, angiitis, one of the pathological mechanisms of neurological lesions in primary Sjögren syndrome, and cyclophosphamide was reported to be particularly effective in patients with primary Sjögren syndrome and spinal cord lesions [

7]. The patient also had spinal cord lesions, and administration of cyclophosphamide was considered; however, we could not obtain patient consent patient nor that of her guardian in the process of explaining the side effects of this medication.

To summarize the results of our treatment methods, if in the case that a first-line medication treatment fails, combination therapy tailored especially to the individual patient's condition ought to be attempted.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download