Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) and combined mirror therapy for inpatient rehabilitation of the patients with subacute stroke.

Methods

Twenty-six patients with subacute stroke were enrolled and randomly divided into three groups: CIMT combined with mirror therapy group, CIMT only group, and control group. Two weeks of CIMT for 6 hours a day with or without mirror therapy for 30 minutes a day were performed under supervision. All groups received conventional occupational therapy for 40 minutes a day for the same period. The CIMT only group and control group also received additional self-exercise to substitute for mirror therapy. The box and block test, 9-hole Pegboard test, grip strength, Brunnstrom stage, Wolf motor function test, Fugl-Meyer assessment, and the Korean version of Modified Barthel Index were performed prior to and two weeks after the treatment.

Results

After two weeks of treatment, the CIMT groups with and without mirror therapy showed higher improvement (p<0.05) than the control group, in most of functional assessments for hemiplegic upper extremity. The CIMT combined with mirror therapy group showed higher improvement than CIMT only group in box and block test, 9-hole Pegboard test, and grip strength, which represent fine motor functions of the upper extremity.

In the patients with stroke, the hemiplegic upper extremity can be a major cause that is responsible for activities of daily living (ADL). The major consideration for rehabilitation clinicians is to promote motor recovery of the arm and hand functions than the lower extremity for the patient after a stroke. With regard to the clinical course of stroke, it is recognized that the patient may achieve a recovery of the lower extremity to some extent before the recovery of the upper extremity [1]. This leads to the speculation that most of the patients no longer need the intensive rehabilitation treatments after a substantial period of time, if they can perform independent gait and maintain ADLs to some extent. In these situations, it may seem insufficient, but the patients are considered to have achieved recovery of the affected upper limbs. According to the previous research, 70%-80% of the patients who survive from stroke have been reported to have persistent impairment of the upper extremity movement [2]. Therefore, the intensive upper limb training based on task-oriented rehabilitation has been frequently performed to manage the stroke patients.

Of the various task-oriented rehabilitation programs, constraint-induced movement therapy (CIMT) is characterized by the restraint of the less effected upper limb accompanied by the shaping and repetitive task-oriented training of more affected upper extremity. This was developed by Taub et al. [3], for the purposes of overcoming the learned nonuse phenomenon of the hemiplegic upper extremity and achieving functional recovery.

In the early stage, the patient wore an orthosis in the less affected upper extremity for two weeks and thereby not performed any exercise, after which, the CIMT was intensively performed on the hemiplegic upper extremity for six hours daily [4]. In an actual clinical setting, however, the patients have problems receiving the intensive occupational therapy for six hours daily. It also remains problematic that the patients have a low level of treatment compliance, because they experience difficulty in maintaining daily activities with the restricted use of the less affected upper extremity and are burdened with other treatments as well. To overcome these limitations, the modified methods have been developed. Moreover, several studies suggested that these modified methods were more effective compared to the palliative occupational treatments [5,6]. In addition, in 1993, Taub et al. [3] reported that the CIMT was effective in improving the functions of the arm, but its effectiveness for the improvement of hands remained obscure. Recent studies have shown that the distal functions were more improved in the group where the hand training program was performed intensively during a certain period of time, as compared to the conventional CIMT [7]. Among the various intensive training programs, the mirror therapy was first introduced by Ramachandran and Rogers-Ramachandran [8] for the first time in 1996. This therapy was effective in treating phantom limb pain based on the defects of visual illusion using a mirror. It has been reported that there were improvements in Fugl-Meyer Assessment and fine motor movement, following a 3- to 4-week course of mirror therapy in the patients with stroke. Thus, it has been shown to be effective in improving the range, velocity, and accuracy of motion in the hemiplegic upper extremity [9]. However, there is a paucity of the data regarding the additional effects of the mirror therapy, when combined with other upper extremity training programs.

In this study, we applied the CIMT where subacute stroke patients performed the intensive treatments for a short period of time. As mentioned above, conventional CIMT is proven to improve the gross motor function, but its effectiveness for the fine motor functions remains obscure. These results can suggest that the CIMT is insufficient for perfectly performing the task-oriented exercises with complex and delicate training on the affected wrist and hand. Therefore, we concomitantly performed the mirror therapy for the purpose of improving the hand functions by focusing on fine motor exercise. The results were compared between the palliative rehabilitation and CIMT only groups to investigate the superiority and the synergic effect of the CIMT combined with mirror therapy for the improvement of the both gross and fine motor functions of hemiplegic upper extremity.

The patients in this study were hospitalized for further evaluation and treatment of stroke at the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine at Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, from October 2012 to May 2013. They have developed subacute stroke when they were enrolled in the present study. A total of 26 patients were fully aware of the study details, were collaborative and willing to participate in the current study, and submitted a written informed consent. Then, they were assigned into three groups by picking a random card with numbers on them: CIMT combined with mirror therapy group (n=8), CIMT only group (n=9), and control group (n=9). The inclusion criteria for the current study are as follows: 1) patients who were diagnosed with hemiplegia due to stroke (onset time of less than six weeks) and have no past history of stroke; 2) patients who could perform an active extension of the affected wrist and more than two fingers at an angle of >10° and an active abduction of the affected thumb at an angle of >10°; 3) patients who can make a simple communication; 4) patients who can receive care by guardians or caregivers; and 5) patients who can maintain a sitting position for more than 30 minutes. The following patients were excluded: the patients with depression who were unable to cooperate in the treatment; the patients who cannot perform the active task training due to the presence of musculoskeletal problems, such as the spasticity of Modified Ashworth Scale (MAS) II or higher; and the patients who have complex regional pain syndrome or secondary adhesive capsulitis.

Prior to the treatment, all of the patients underwent box and block test, 9-hole Pegboard test, grip strength, Brunnstrom stage, Wolf motor function test, and Fugl-Meyer Assessment (upper extremity, total score) to evaluate the motor functions of the hemiplegic upper extremity. The Korean version of Modified Barthel Index (K-MBI) was used to compare the improvements in the performance of ADL. In addition, we examined the degree of the improvement between the groups to analyze the effects of the treatment outcomes. For the evaluation of the experimental groups, we performed the above tests prior to the treatment and two weeks thereafter, and the results were compared between the three groups by the blinded observers.

In CIMT combined with mirror therapy group and CIMT only group, patients wore a specially designed orthosis to suppress the motion of the unaffected upper extremity for a total of two weeks. The patients received intensive training for five days a week except for the weekend, for a total of six hours (2 hours in the therapy room and 4 hours in the inpatient room) a day except for sleeping hours. During the time, intensive fine motor exercise of the hemiplegic upper extremity was performed under the supervision of occupational therapist. The mirror therapy was performed for 30 minutes a day for five days a week, for two weeks. During the mirror therapy, the patients performed flexion/extension of the shoulder, elbow, wrist, finger, and pronation/supination of the forearm according to the verbal commands. They were also recommended to perform the objective task training with the unaffected hands.

The patients of the control group were recommended to perform the self-exercise program as well as the palliative rehabilitation therapy that is routinely recommended for the hospitalized patients. The patients of the CIMT combined with mirror therapy group did not receive the palliative rehabilitation therapy, and the mirror therapy was performed during hours when the CIMT was not done. The patients of the CIMT only group were recommended to perform CIMT, palliative rehabilitation therapy, and additional self-exercise program to minimize the difference in the total amount of treatment time between the three groups. Moreover, we also maximized the involvement of full-time nurses and guardians to improve the treatment compliance and to lower the drop-out rate. Furthermore, we made it easier to monitor the length of time the patients wear the orthosis, by enrolling hospitalized patients in this study rather than the outpatients (Fig. 1).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 10.0 for Window (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). To compare the sex, age, causes and duration of stroke, and affected side between the groups, we performed the Kruskal-Wallis test for the age and stroke duration, and Fisher exact test for other categorical data. In addition, we also applied the Wilcoxon signed-ranks test to compare changes in the functions of the upper limbs and daily activities, between prior to and following the treatment in each group. We used the Kruskal-Wallis test to compare the degree of changes in these parameters, between prior to and following the treatment. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We performed a post-hoc analysis to analyze the difference between the three groups. In addition, we also performed the Mann-Whitney U test to analyze the difference between the two groups among the three groups. We adopted the Bonferroni correction to correct the type I errors and set a level of statistical significance at p=0.017.

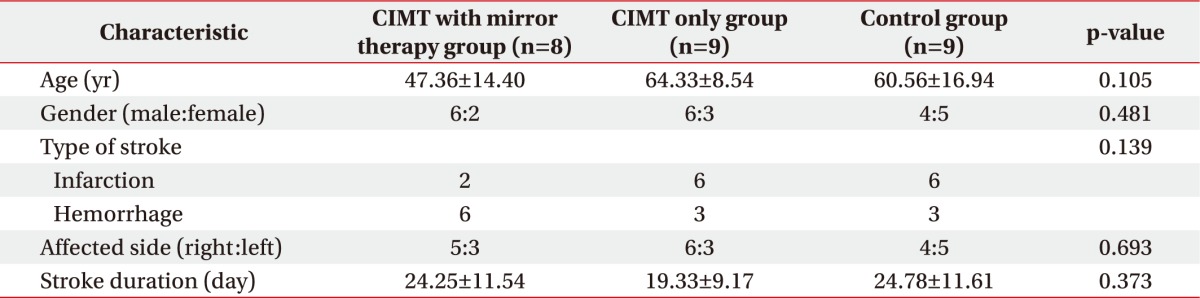

We compared the baseline characteristics among 17 patients of the experimental groups and 9 patients of the control group, who received treatments for two weeks. There were no statistically significant differences in the sex, age, causes of stroke, sites of stroke, and affected sides between the three groups (Table 1).

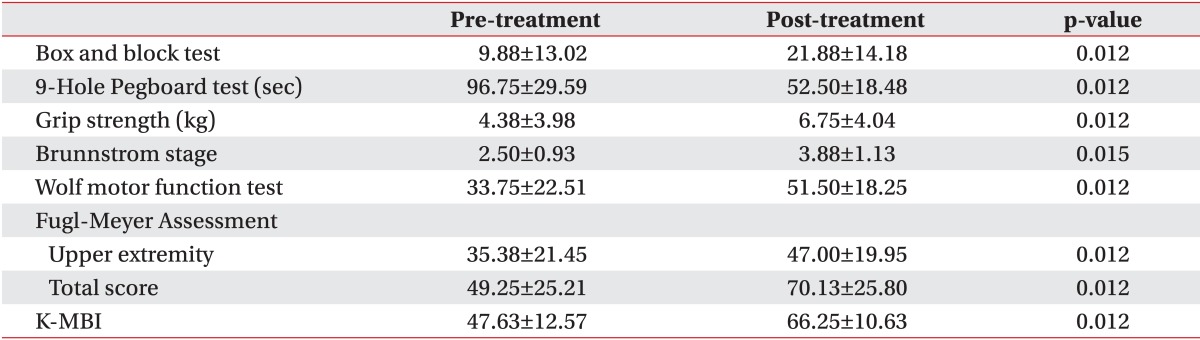

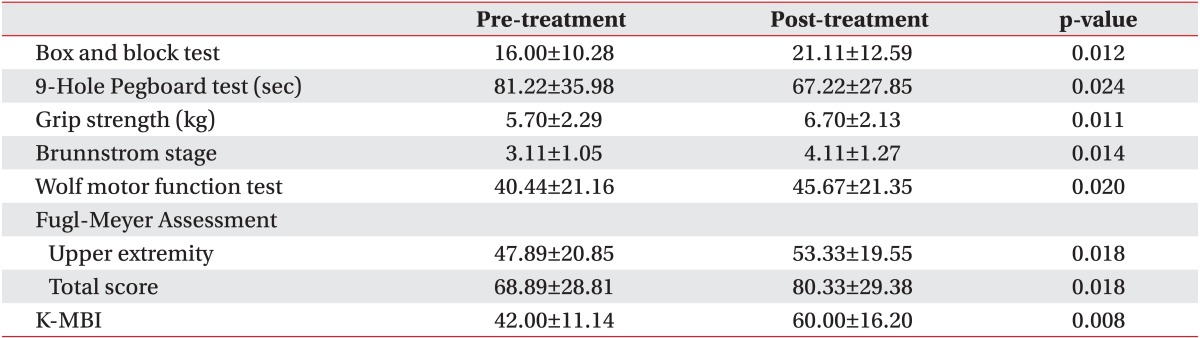

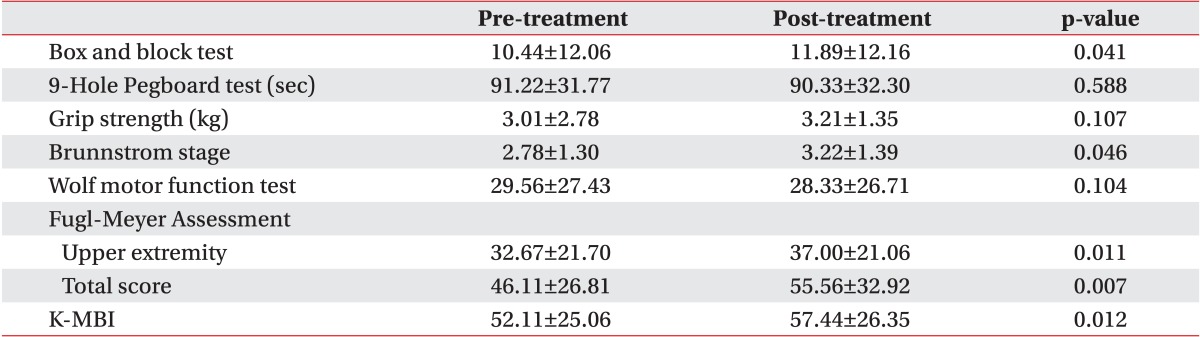

We also compared the degree of the functions of the upper extremity and the performance of daily activities before and after the treatment in each group. The baseline assessments had no statistically significant difference between the groups. All parameters in the CIMT combined with mirror therapy group and the CIMT only group showed significant improvements. In the control group, there were statistically significant improvements in the box and block test, Brunnstrom stage, Fugl-Meyer Assessment, and K-MBI (p<0.05) (Tables 2,3,4).

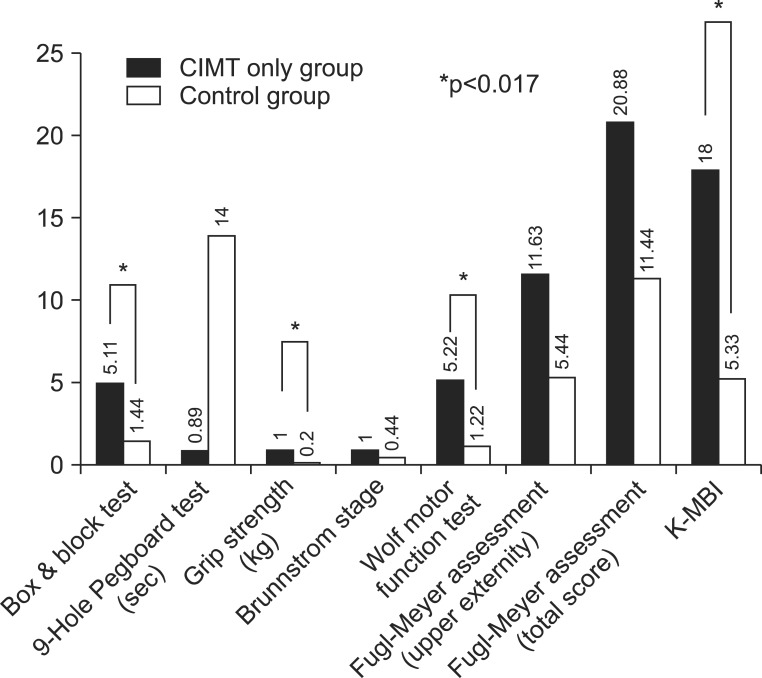

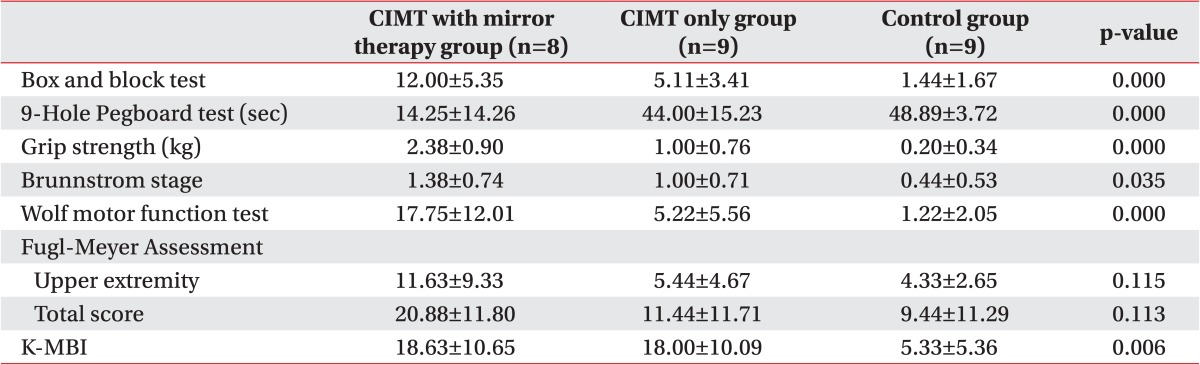

We compared the degree of changes between prior to and following the treatment in each group. The significant improvements were found in all of the parameters, except in Fugl-Meyer Assessment in all three groups (p<0.05) (Table 5). Therefore, we performed a post-hoc analysis to examine whether there is a difference between the three groups. This showed that there were significant differences as follows: the box and block test, 9-hole Pegboard test, and grip strength test between the CIMT combined with mirror therapy group and the CIMT only group; the box and block test, grip strength, Wolf motor function test, and MBI between the CIMT only group and the control group; and the box and block test, 9-hole Pegboard test, grip strength, Wolf motor function test, and MBI between the CIMT combined with mirror therapy group and the control group (p<0.017) (Figs. 2,3,4).

The stroke is one of the major diseases that may cause disabilities [10]. The impaired muscle strength after a stroke poses a therapeutic challenge for the patients, guardians, and specialists in rehabilitation therapy [11]. In particular, the learned nonuse phenomenon of the affected upper extremity is characterized by the tendency to use the less affected upper extremity for the purpose of habitually performing the functional tasks [11,12]. As described, if hemiplegic patients use the unaffected upper extremity, they would lose the functional independence. This leads to the speculation that the patients would increasingly use the hemiplegic upper extremity and eventually would achieve a functional recovery, if they concomitantly receive short-term intensive rehabilitation treatments, such as CIMT and mirror therapy, following the onset of symptoms [13]. These intensive rehabilitation treatments for the upper extremity training may be based on the structural plasticity that the gray and white matter undergo following the onset of stroke [14,15]. In the association with structural alterations in the gray matter following the short-term intensive rehabilitation treatments, such as the CIMT, it has been shown that the size of contrast-enhanced bilateral sensorimotor cortex was increased on the voxel-based morphometry on T1-weighted magnetic resonance imaging scans. In addition, the previous studies have also shown that there is a significant proportional correlation between the size of contrast-enhanced bilateral sensorimotor cortex and the degree of the functional recovery of the hemiplegic upper extremity [16]. To explain the mechanisms of the mirror therapy, the transcranial magnetic stimulation was performed during the mirror illusion in normal healthy individuals. It was shown that there was an increase in the activity of the primary motor cortex (M1) corresponding to the contralateral hand on the mirror [17]. The mirror neurons have been disclosed to be involved in the effects of the mirror therapy; they are bimodal visuomotor neurons and are activated when there are action observation, psychological stimulation, and action execution [18]. This result implies that the additional treatment effects of CIMT and mirror therapy might be based on different mechanisms.

Controversial opinions exist regarding the order and pattern of the functional recovery of the upper extremity. It is frequently noted, however, that the patients usually achieve recovery from proximal to distal extremity. The conventional CIMT is effective in improving the gross motor function. It has also been reported, however, that its effectiveness for the minor motor functions remains obscure [7]. At our medical institution, we performed the conventional CIMT concomitantly with the mirror therapy to improve the hand functions by focusing on the fine motor exercise. This was decided concerning of a possibility that we would achieve the fine motor functions to lesser extents, if we only perform CIMT. In the present study, we compared the difference in the improvements between prior to and following the treatment among the three groups. This finding showed that the degree of the improvement in the box and block test and 9-hole Pegboard test, and the indicators for the fine motor functions as well as the grip strength were all significantly higher in the CIMT combined with mirror therapy group compared to the CIMT only group. These results indicate that the mirror therapy combined with the CIMT would be effective in improving the indicators for the fine motor functions in the clinical setting.

The limitations of the current study are as follows. 1) We evaluated the treatment outcomes at baseline and two weeks after the treatment. Therefore, we did not examine whether our methods were also effective in maintaining the functions of the hemiplegic upper extremity over a long-term period. 2) Our results cannot be completely generalized, because we enrolled a small number of patients and the mean age of the three participating groups showed significant difference. As a pilot study, however, our results contain a clinical significance for combining two intensive rehabilitation treatments for the upper extremity, and this approach deserves further large-scale studies. 3) We used the Mini-Mental Status Examination, MAS scale, and manual muscle test to initially screen the patients. Therefore, we did not examine whether the degree of functional recovery is correlated with the cognitive functions, muscle rigidity, muscle strength, and functional status. 4) There were no consistent criteria for the location or size of lesions prior to the current study. It is probable that the treatment outcomes might be subjected to the degree of the functional defects of the upper extremity, due to the arrangement of the cerebral cortex according to the lesions such as the proximal or distal dominance or the potential visuospatial functions affecting the motor functions.

Finally, with regard to the functional recovery of the upper extremity, we propose the following matters. It would be mandatory to standardize the personalized, inconsistent, task-specific performance depending on the degree of recovery in a clinical setting. There is a high possibility that there might be a great discrepancy in the degree of the functional recovery, unless there are established criteria for selecting the appropriate treatment methods.

It would also be mandatory to perform a systematic review of the tools that are used to assess the outcomes of the upper extremity training. In detail, the Wolf motor function test is routinely performed for the patients where the active extension of the affected wrist and more than two fingers is possible at an angle of more than 10°. We set criteria for defining the minimum muscle strength. In the current study, however, we encountered many unresolved problems to enroll the patients, as some patients could not perform any of the tasks although they were compatible with the criteria. In addition, there was a great variability in the testing time between the patients. This leads to the speculation that further studies are warranted to identify the tools that are specific for the degree of the functional recovery.

In conclusion, after two weeks of treatment, the CIMT combined with or without mirror therapy groups showed more improvement than the control group in most of functional assessments on hemiplegic upper extremity. The CIMT combined with mirror therapy group achieved more significant improvement than the CIMT only group in box and block test, 9-hole Pegboard test, and grip strength, which represent fine motor functions of the upper extremity.

References

1. Basmajian JV. The Winter of Our Discontent: breaking intolerable time locks for stroke survivors. The 38th annual John Stanley Coulter lecture. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1989; 70:92–94. PMID: 2916934.

2. Pang MY, Harris JE, Eng JJ. A community-based upper-extremity group exercise program improves motor function and performance of functional activities in chronic stroke: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006; 87:1–9. PMID: 16401430.

3. Taub E, Miller NE, Novack TA, Cook EW 3rd, Fleming WC, Nepomuceno CS, et al. Technique to improve chronic motor deficit after stroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993; 74:347–354. PMID: 8466415.

4. Taub E, Wolf SL. Constraint induced movement techniques to facilitate upper extremity use in stroke patients. Top Stroke Rehabil. 1997; 3:38–61.

5. Dromerick AW, Edwards DF, Hahn M. Does the application of constraint-induced movement therapy during acute rehabilitation reduce arm impairment after ischemic stroke? Stroke. 2000; 31:2984–2988. PMID: 11108760.

6. Page SJ, Sisto S, Johnston MV, Levine P, Hughes M. Modified constraint-induced therapy in subacute stroke: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002; 83:286–290. PMID: 11833037.

7. Peurala SH, Kantanen MP, Sjogren T, Paltamaa J, Karhula M, Heinonen A. Effectiveness of constraint-induced movement therapy on activity and participation after stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Rehabil. 2012; 26:209–223. PMID: 22070990.

8. Ramachandran VS, Rogers-Ramachandran D. Synaesthesia in phantom limbs induced with mirrors. Proc Biol Sci. 1996; 263:377–386. PMID: 8637922.

9. Altschuler EL, Wisdom SB, Stone L, Foster C, Galasko D, Llewellyn DM, et al. Rehabilitation of hemiparesis after stroke with a mirror. Lancet. 1999; 353:2035–2036. PMID: 10376620.

10. Bonifer NM, Anderson KM, Arciniegas DB. Constraint-induced movement therapy after stroke: efficacy for patients with minimal upper-extremity motor ability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005; 86:1867–1873. PMID: 16181956.

11. Taub E. Somatosensory deafferentation research with monkeys: implications for rehabilitation medicine. In : Ince LP, editor. Behavioral psychology in rehabilitation medicine: clinical applications. New York: Williams & Wilkins;1980. p. 371–401.

12. Taub E. Movement in nonhuman primates deprived of somatosensory feedback. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 1976; 4:335–374. PMID: 828579.

13. Wilkinson PR, Wolfe CD, Warburton FG, Rudd AG, Howard RS, Ross-Russell RW, et al. A long-term follow-up of stroke patients. Stroke. 1997; 28:507–512. PMID: 9056603.

14. Schaechter JD, Moore CI, Connell BD, Rosen BR, Dijkhuizen RM. Structural and functional plasticity in the somatosensory cortex of chronic stroke patients. Brain. 2006; 129(Pt 10):2722–2733. PMID: 16921177.

15. Dancause N, Barbay S, Frost SB, Plautz EJ, Chen D, Zoubina EV, et al. Extensive cortical rewiring after brain injury. J Neurosci. 2005; 25:10167–10179. PMID: 16267224.

16. Gauthier LV, Taub E, Perkins C, Ortmann M, Mark VW, Uswatte G. Remodeling the brain: plastic structural brain changes produced by different motor therapies after stroke. Stroke. 2008; 39:1520–1525. PMID: 18323492.

17. Garry MI, Loftus A, Summers JJ. Mirror, mirror on the wall: viewing a mirror reflection of unilateral hand movements facilitates ipsilateral M1 excitability. Exp Brain Res. 2005; 163:118–122. PMID: 15754176.

18. Fadiga L, Craighero L. Electrophysiology of action representation. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2004; 21:157–169. PMID: 15375346.

Fig. 2

Difference in percentage of assessment at baseline and after treatment in CIMT only group vs. control group (*p<0.017). CIMT, constraint-induced movement therapy; K-MBI, Korean version of Modified Barthel Index.

Fig. 3

Difference in percentage of assessment at baseline and after treatment in CIMT with mirror therapy group vs. control group (*p<0.017). CIMT, constraint-induced movement therapy; K-MBI, Korean version of Modified Barthel Index.

Fig. 4

Difference in percentage of assessment at baseline and after treatment in CIMT with mirror therapy group vs. CIMT only group (*p<0.017). CIMT, constraint-induced movement therapy; K-MBI, Korean version of Modified Barthel Index.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download