This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Chronic, refractory abdominal pain without a metabolic or structural gastroenterological etiology can be challenging for diagnosis and management. Even though it is rare, it has been reported that such a recurrent abdominal pain associated with radicular pattern can be derived from structural neurologic lesion like spinal cord tumor. We experienced an unusual case of chronic recurrent abdominal pain that lasted for two years without definite neurologic deficits in a patient, who has been harboring thoracic spinal cord tumor. During an extensive gastroenterological workup for the abdominal pain, the spinal cord tumor had been found and was resected through surgery. Since then, the inexplicable pain sustained over a long period of time eventually resolved. This case highlights the importance of taking into consideration the possibility of spinal cord tumor in differential diagnosis when a patient complains of chronic and recurrent abdominal pain without other medical abnormalities.

Go to :

Keywords: Abdominal pain, Spinal cord tumor

INTRODUCTION

In rare cases, spinal cord tumor can cause an abdominal pain as the initial symptom prior to some neurologic impairments [

1]. Therefore, in early stage of spinal cord tumor, it can be misdiagnosed as other gastroenterological disorders, musculoskeletal problem, or psychopathologic condition. This wrong diagnosis may disrupt quality of life and social integration of the patient due to persistent pain, and it will be followed by progression of neurologic deficit. Hence, in an ambiguous recurrent abdominal pain, considering the possibility of spinal cord tumor is important for proper treatment and better prognosis.

In this work, we studied a rare case of a patient with chronic recurrent abdominal pain caused by harboring thoracic spinal cord tumor. We lay emphasis on the fact that a spinal cord lesion is an uncommon, but important, cause of inexplicable abdominal pain, which is often ignored by numerous clinicians despite the existence of subtle clues.

Go to :

CASE REPORT

A 47-year-old male, with no previous medical history, visited the outpatient Department of Rehabilitation in our hospital with a chief complaint of severe left upper abdominal pain. In fact, his abdominal pain initiated 2 years ago, and the symptoms had been progressing for past several months. He denied of any history of trauma prior to the onset of the pain. He underwent extensive gastroenterological workup including upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and computed tomography of abdomen, but the results showed no significant abnormalities. The abdominal pain was described as somewhat pricking but not obvious. At that time, he had normal motor, sensory, bladder, and bowel functions, and he did not show upper motor neuron sign. Conservative cares were carried out with prescriptions of pain medications and anti-inflammatory analgesic medications.

However, with the lapse of time, the patient's symptoms continued and became severe. The pain now measured 5 to 6 on visual analog scale and lasted for half an hour to a few hours, which was unlinked to position, movement, food intake, or defecation. He eventually consulted a surgeon in the general surgery department and was admitted to our hospital for more evaluation of those symptoms. There was no history of sweating, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, fever, chills, or weight loss. On physical examination, there were no gastrointestinal signs on the abdomen, except for mild tenderness on epigastrium. Laboratory test data including complete blood count, urinalysis, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein, serum electrolytes, liver enzyme, and amylase were all within the normal ranges. Electrocardiography monitoring showed no abnormalities and the follow-up computed tomography revealed no apparent gastroenterological pathology or musculoskeletal problems.

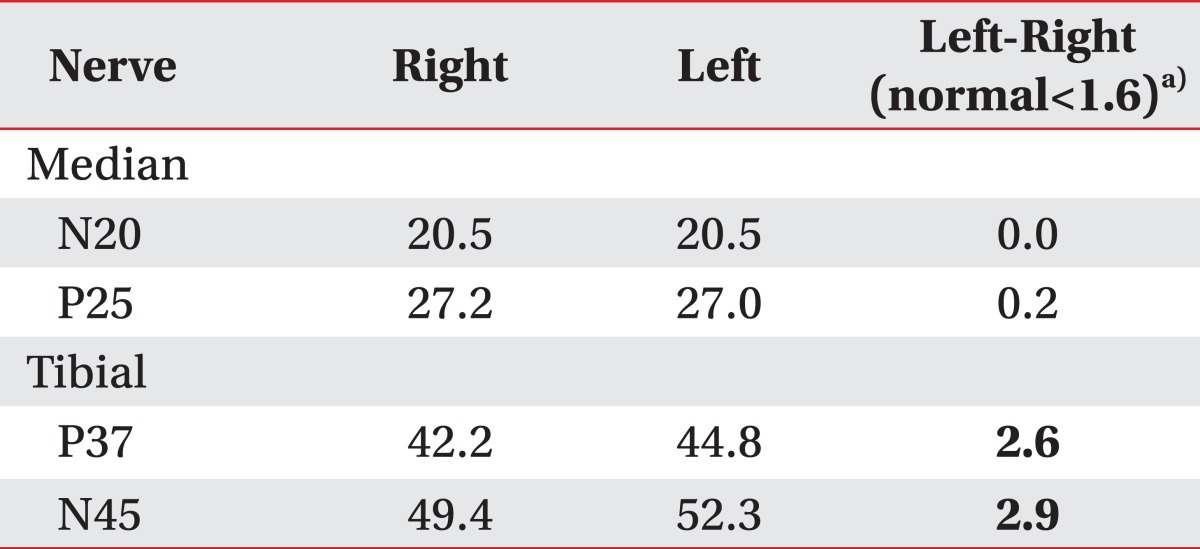

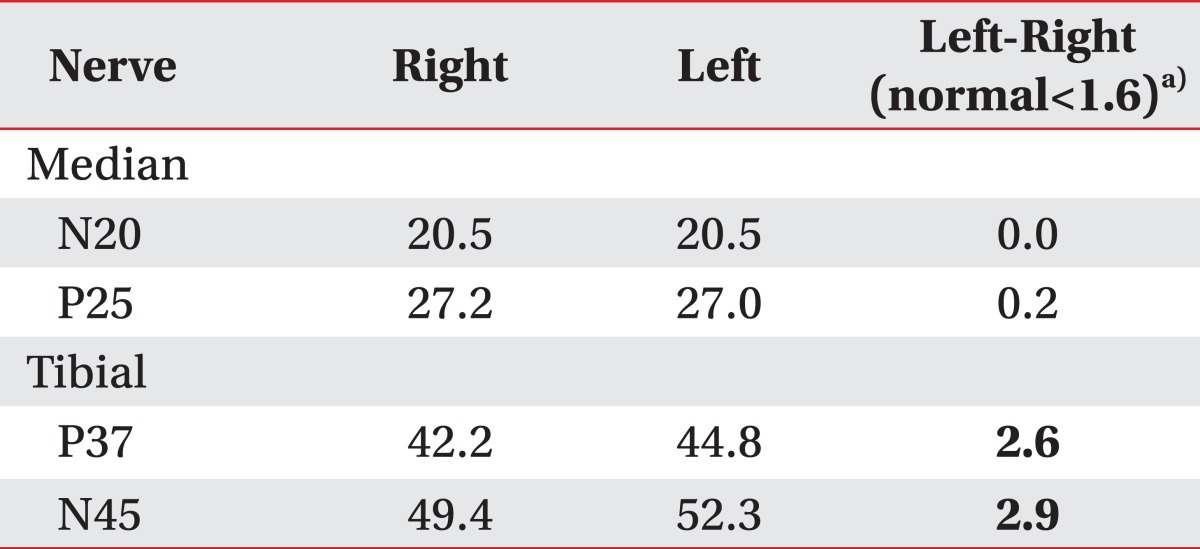

To rule out neurologic origins, the patient was referred to our rehabilitative medicine department. We first asked him detailed questions about his neurologic condition, and we reviewed his subjective feelings about the weakness in lower extremities despite the good to normal score on manual muscle test. Additionally, he complained of very mild hypoesthesia below the left T5 dermatomes. So, we performed the electrophysiological study to evaluate neurogenic deficit. Nerve conduction study and electromyography examination showed no evidences of peripheral neuropathy or radiculopathy. But in the test of somatosensory evoked potential (SEP) recorded at the brain cortex, the latencies of bilateral tibial nerve SEP stimulated at ankle were relatively delayed, while that of bilateral median nerve SEP stimulated at wrist were within the normal range. The tibial nerve SEP for the left side were slower than that of the right side. From the results of this SEP study, we found that the thoracolumbar spinal cord lesion affected more on the left side (

Table 1).

Table 1

Initial 1 channel somatosensory evoked potentials of bilateral median and tibial nerves (unit, ms)

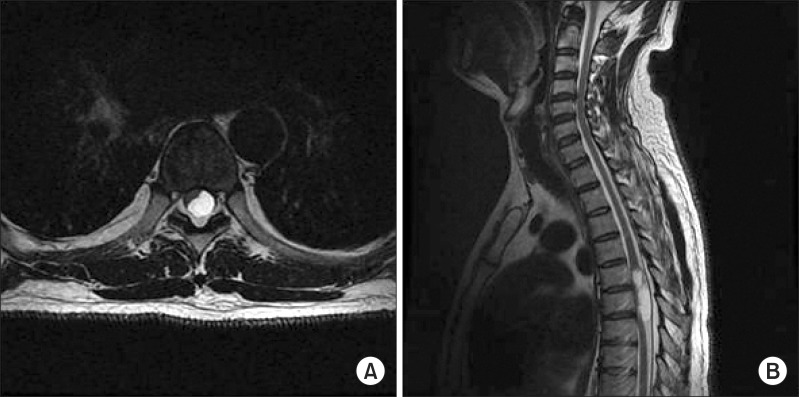

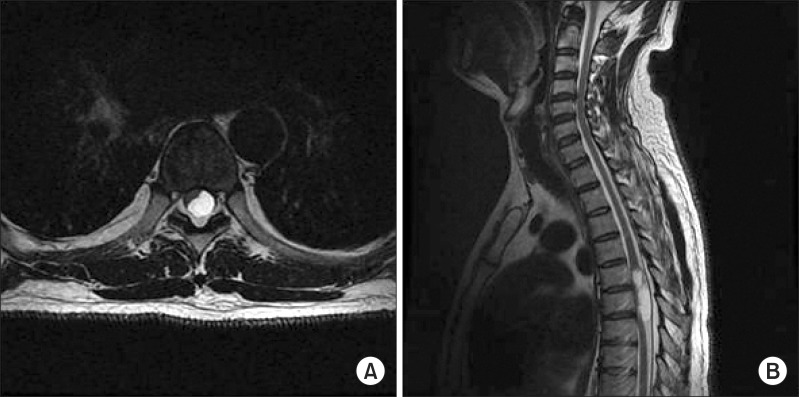

As a next step for the diagnosis, thoracolumbar magnetic resonance imaging was performed. About 1×4.5-cm in size, well defined cystic mass in spinal canal of T5-T7 level was shown with bright intensity on T2-weighted image, and the mass that was more involved within the left side was compressing the spinal cord (

Fig. 1).

| Fig. 1Initial thoracolumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (A) Axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrating about 1×4.5-cm size, well defined cystic mass of T5-7 intradural extramedullary level. Note extensive compression of thoracic spinal cord. (B) Sagittal T2-weighted MRI demonstrating large intradural extramedullary mass at T6 level, occupying most of (the) spinal canal but more involving in (the) left side.

|

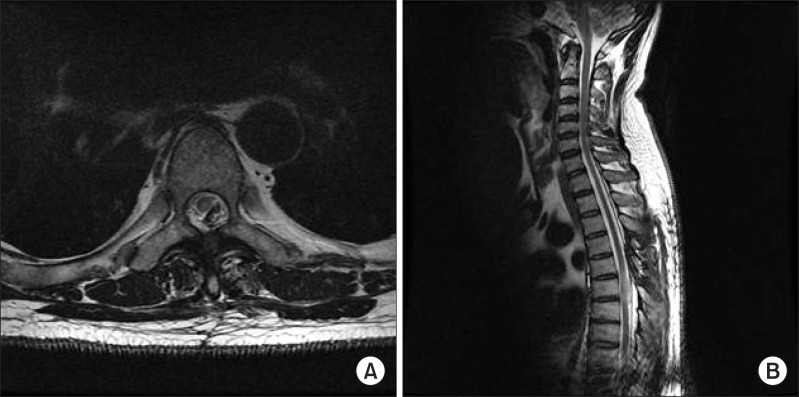

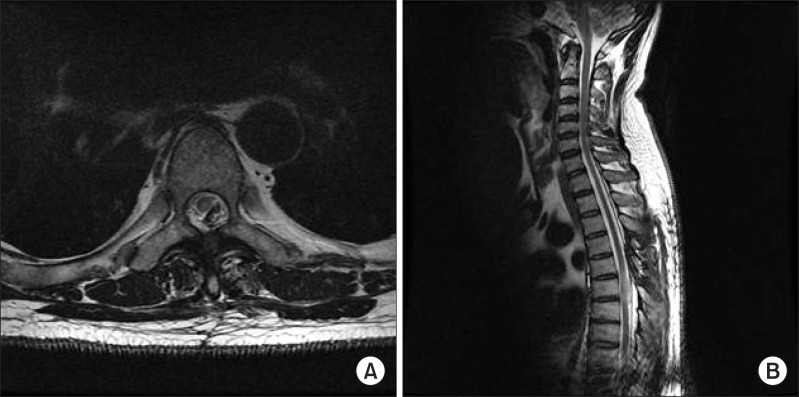

Finally, the patient was referred to neurosurgery and underwent a tumor removal, shortly thereafter (

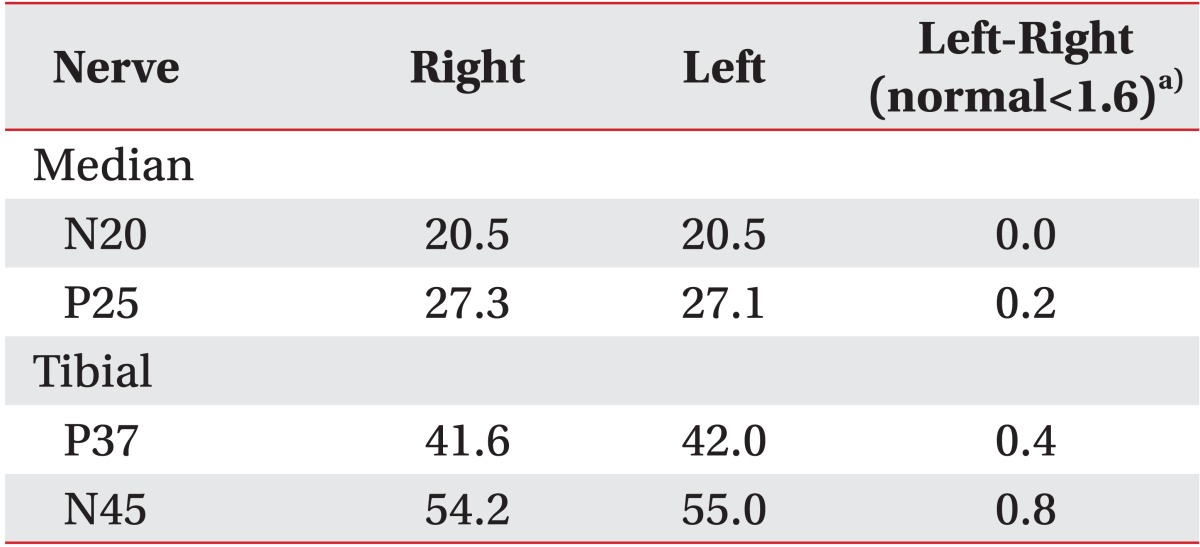

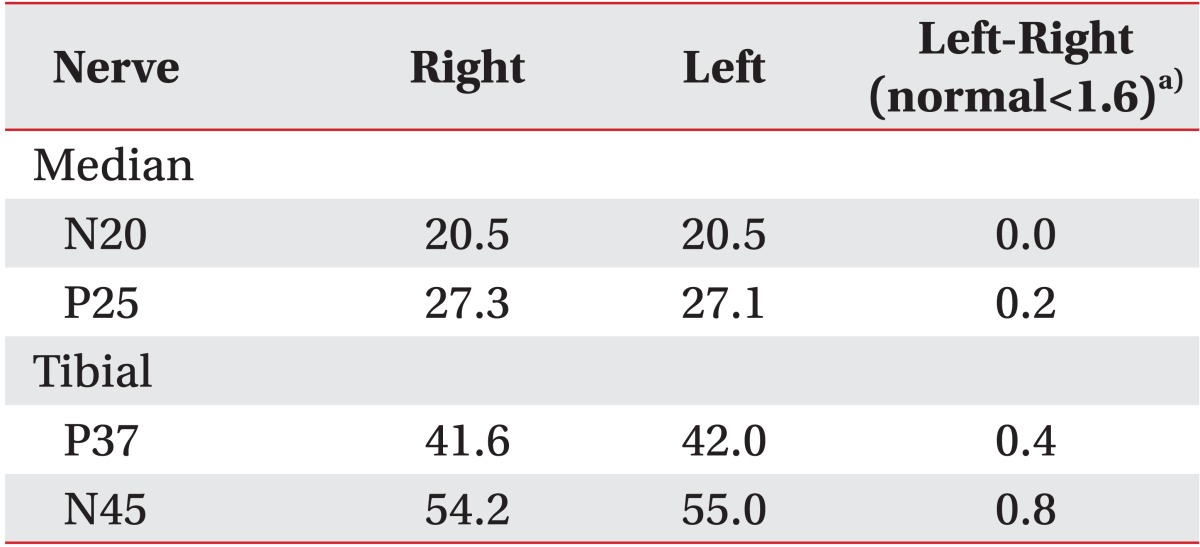

Fig. 2). Microscopic pathology established the tumor as a schwannoma. After the surgery, the left upper abdominal pain from which he suffered for a long time eventually resolved. In the follow-up examination of SEP, the latencies of bilateral tibial nerve SEP stimulated at ankle were still delayed, but the latencies between bilateral tibial nerve somatosensory pathways disappeared (

Table 2).

| Fig. 2Follow-up thoracolumbar magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) after tumor resection. (A) Axial T2- and (B) sagittal T2-weighted MRIs demonstrating removal of spinal cord mass at T6 level.

|

Table 2

Follow-up somatosensory evoked potentials of bilateral median and tibial nerves (unit, ms)

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Spinal cord tumors are rare and those associated with abdominal pain are even rarer [

2]. The most common clinical finding of spinal cord tumor is pain, which is also the first symptom prior to neurologic deficit [

2]. But the tumor-specific pain generally appear as a severe back or radicular pain, and not as an abdominal pain [

3]. When the patients with spinal pathology complain of abdominal pain, they usually already have advanced neurologic symptoms like numbness or weakness [

4]. For this reason, it is unusual to encounter a patient who only has chronic abdominal pain without any signs of neurological deficit. Hence, clinicians can experience difficulty in diagnosis in such a case.

In the previously reported cases on spinal cord tumor with inexplicable abdominal pain, many physicians initially failed to address the etiology of chronic abdominal pain and continued only with conservative care. This results in delay of diagnosis and exacerbation of the disease, until other neurologic impairments arise [

5,

6]. Kato et al. [

7] reported that the intervals of delay, from onset of the initial symptoms to diagnosis of harbored spinal cord tumors, were 8.1 to 16.9 months. These initial symptoms, however, does not include the abdominal pain. Therefore, if patients complain only of the atypical symptoms, especially as abdominal pain, proper diagnosis could be delayed even more. When the patient in this study was referred to our department, he was already showing very mild neurologic deficit, hypoesthesia, and lower extremities weakness, due to delayed diagnosis, in spite of a long history.

The abdominal pain is most likely to result from the irritation of thoracic nerve root and from spinothalamic tract injury derived from spinal cord compression by tumor mass [

8,

9]. Our patient could hardly describe the characteristic of the pain. Similarly, the pain derived from neurological source have specific features of vague, uncharacteristic, and unpleasant sensation in the painful area that are irrelevant with body position, and are related with neurologic dermatome along radicular features associated with burning with or without tingling and prickling sensation [

2]. Clinicians frequently encountering patients with abdominal pain normally would make a differential diagnosis of common diseases first. However, they now should also be familiar that spinal cord pathology can be a cause of abdominal pain as well. In spite of the rarity of spinal neoplasm, a keen awareness of atypical clinical findings in the negative results of gastroenterological evaluation is necessary, in order to make a diagnosis and manage the patients with spinal cord tumor, before progressing into the neurological abnormalities. A preferably early diagnosis and subsequent therapy of tumor can prevent irreversible neurological deficits caused by the mass effect on the spinal cord, and it can improve the prognosis and quality of life of the patients [

4,

10].

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download