Abstract

Dysphagia secondary to peripheral cranial nerve injury originates from weak and uncoordinated contraction-relaxation of cricopharyngeal muscle. We report on two patients who suffered vagus nerve injury during surgery and showed sudden dysphagia by opening dysfunction of upper esophageal sphincter (UES). Videofluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation of UES was performed. We confirmed an early improvement of the opening dysfunctions of UES, although other neurologic symptoms persisted. While we did not have a proper comparison of cases, the videofluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation of UES is thought to be helpful for the early recovery of dysphagia caused by postoperative vagus nerve injury.

Upper esophageal sphincter (UES) is held closed, and it opens briefly during each swallow. Main factors in the opening of UES are relaxation of cricopharyngeus, forward elevation of larynx and hydrostatic pressure of descending bolus. Both vagus and glossopharyngeal nerves play an important role in the relaxation of cricopharyngeus [1]. Injury to these nerves can cause UES opening dysfunction.

Several previous studies conducted videofluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation of UES on cricopharyngeal dysfunction from radiation therapy and stroke [2,3]. We hypothesized that balloon dilatation may also be helpful in extracranial vagus nerve injury occurred in operation. We performed videofluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation of UES in two cases and confirmed improvement of UES opening without complication.

A 62-year-old man had cervical spinal cord injury (neurological level, C8; American Spinal Injury Association D [ASIA-D]) after accidental fall. He underwent anterior fixation on C3-C7 and laminoplasty by posterior approach after four weeks, on the same level. After the second operation, sudden dyaphagia occurred. The patient could not swallow food and showed aspiration sign during mealtime. On physical examination, he presented hoarseness and deviated tongue to the left. Left vocal cord palsy was found on laryngoscopy. He was diagnosed as palsies of left vagus and hypoglossal nerves.

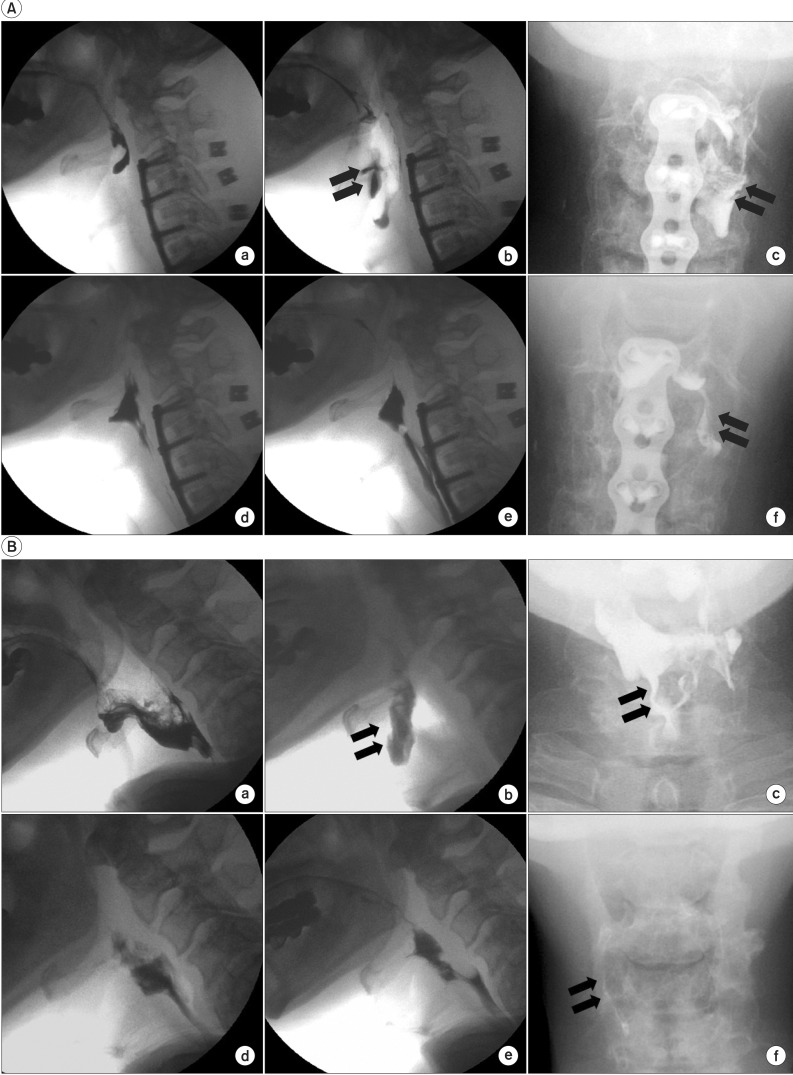

For the treatment plan, videofluoroscopic swallow study (VFSS) with 2 mL and 5 mL of radiopaque yogurt pudding and mineral water was done. The patient could not swallow the food, and aspiration was evoked by an overflowing of pyriform sinus remnant (Fig. 1A-a, b, c). For 5 weeks, he was nourished by nasogastric tube and had conventional dysphagia therapy for UES opening, which included manual laryngeal elevation and Shaker exercise for five days a week. The patient showed no improvement.

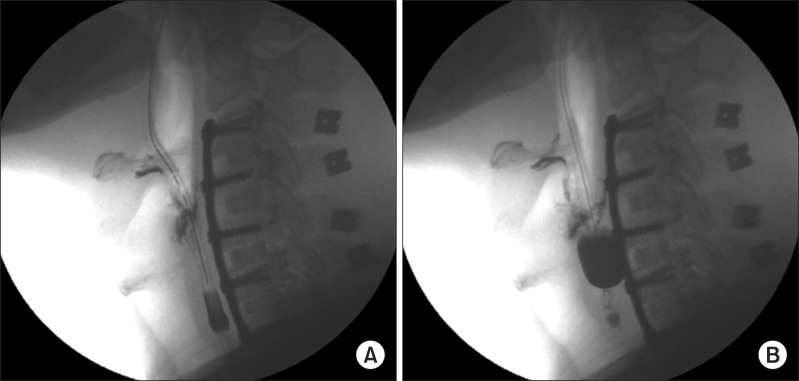

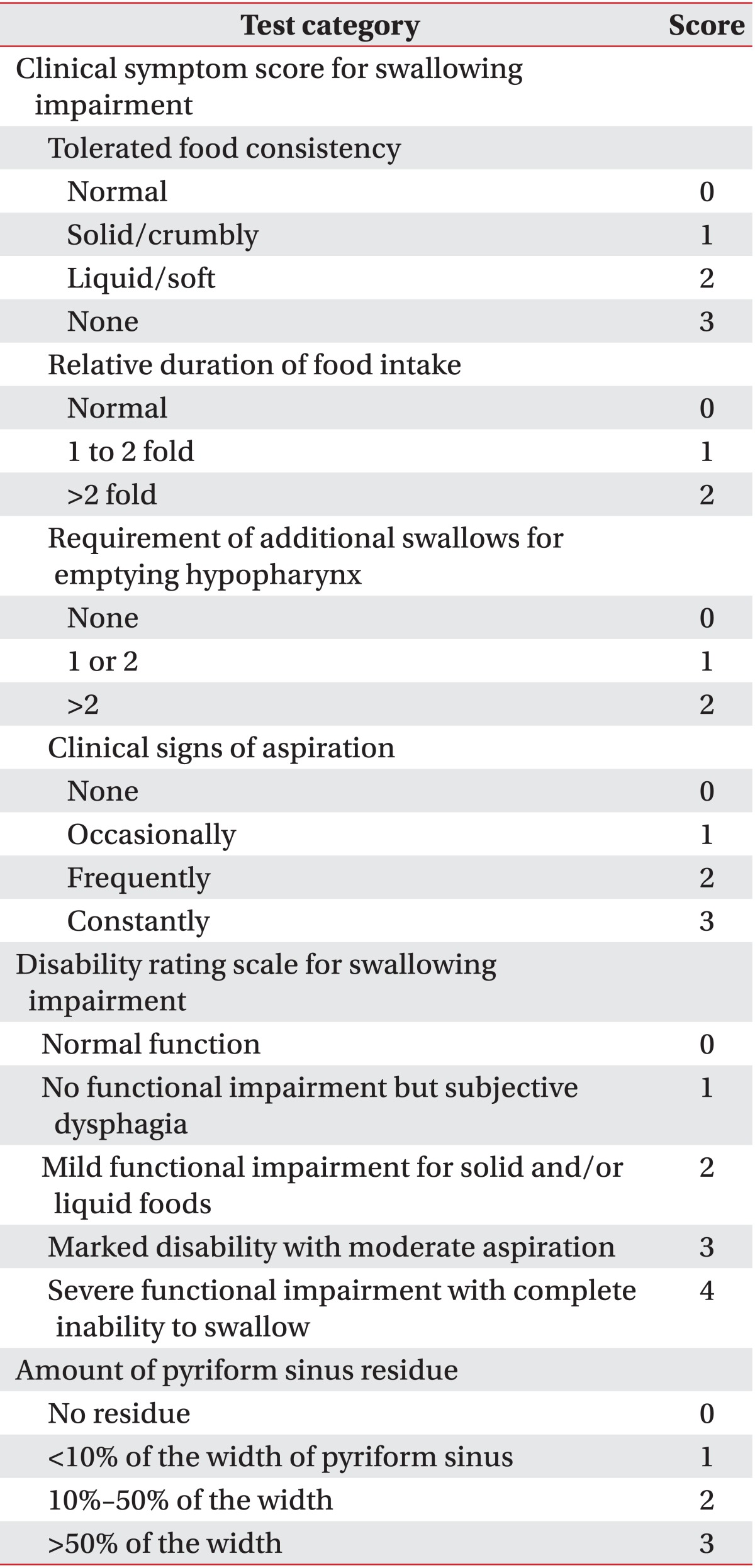

We performed videofluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation of UES. Checking images on fluoroscopy, 16-Fr Foley catheter with deflated balloon was inserted through the nasal cavity until the balloon part of catheter was estimated to be under the lower margin of UES. Then balloon was gently inflated using 3 mL of contrast media, and we pulled the inflated catheter slightly upward, locating the balloon at middle of UES (Fig. 2). We kept balloon at UES for 30 seconds so that UES could be dilated mechanically. If the balloon was thrown upward from UES, we promptly deflated and repositioned the balloon at UES and continued the procedure. The procedure was done ten times with one minute interval per session. At the end of each session, VFSS with yogurt pudding was done. When UES opening improved as much as possible to start pudding intake, VFSS was performed three days after the session. When VFSS demonstrated no aspiration and pyriform sinus residue was less than 10% of width, the ballooning treatment was terminated. Before and after ballooning, we measured clinical symptom score, disability rating scale for swallowing impairment and the amount of pyriform sinus residue [4] (Table 1).

After six ballooning sessions with a periodic interval of five days per month, pyriform sinus residue decreased from grade 3 to 1 (Fig. 1A-c, f) without aspiration (Fig. 1A-e). The patient started oral intake. The clinical symptom score and disability rating score also improved from 9 to 0 and 4 to 0, respectively. Other neurologic symptoms like tongue deviation, vocal cord palsy and hoarseness continued for four months after the termination of ballooning. Dysphagia has not recurred for over a year.

A 72-year-old man who had a retropharyngeal abscess underwent abscess removal surgery. After the operation, he complained of dysphagia. He was diagnosed as right vagus nerve palsy, showing hoarseness and abnormal position of right vocal cord on laryngoscopy.

VFSS demonstrated a firmly closed UES. The patient could not swallow food and liquid through UES at all, and aspiration occurred by pyriform sinus residue with grade 3 (Fig. 1B-a, b, c). He was nourished by nasogastric tube for six weeks and had conventional dysphagia therapy without any improvements. He received eleven trials of videofluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation for two months with the same method as described in case 1. The UES opening improved, and no aspiration was observed in the final VFSS (Fig. 1B-d, e). He could swallow 5 mL of yogurt pudding in four swallowing efforts to reach grade 0 of pyriform sinus residue (Fig. 1B-f) and started oral intake. The clinical symptom score and the disability rating score improved from 10 to 4 and 4 to 1, respectively. Other neurologic symptoms continued for two months after the termination of ballooning. Dysphagia has not recurred for over a year.

For treatment of UES opening dysfunction, cricopharyngeal myotomy, botulinum toxin injection into cricopharyngeus and balloon dilatation are performed [2,4-6]. Cricopharyngeal myotomy is the best treatment with long-lasting results, but needs general anesthesia and has a risk of complications, such as mediastinitis, paralysis of epiglottis, hemorrhage, and perforation [5]. Botulinum toxin injection is safe and has low risk of complications, but is expensive with limited effect, lasting for 4-7 months [7]. Balloon dilatation was reported to be an effective treatment for its lower risk of complications and relatively long-lasting effect [2,6]. Solt et al. [6] performed balloon dilatation using 12-15 mm diameter catheter through endoscope and under fluoroscopic guidance. This method has a limitation that it should be performed only by an endoscopy specialist. Clary et al. [8] used a larger 60-Fr esophageal dilator. This also needs a laryngoscopist; and patients should undergo sedation or general anesthesia [8]. Furthermore, minor complications, such as mucosal tear, laryngospasm, and low postprocedural oxygen saturation, were observed in 10% of patients. Dou et al. [9] compared two different modes (active/passive) of ballooning with urethral catheter. Although passive mode procedure is very similar to ours, they performed dilatation without fluoroscopic guidance, which can cause unsuccessful targeting of the UES.

We modified the method of Kim et al. [2] using Foley catheter, which is easy, safe and less painful, as Foley catheter is more flexible and smaller in diameter than endoscope. Kim et al. [2] used the swallowing reflex to make an inflated balloon pass the UES. We passed deflated balloon through UES and located inflated balloon at middle of UES. Because gag reflex was rarely induced, our patients rarely complained of discomfort during procedure. We repeated sessions with a 5-day interval, and consistent improvements were observed in a series of post-dilatation VFSS.

UES opening is controlled by vagus and glossopharyngeal nerve. Case 1 patient had both vagus and hypoglossal nerve injuries. However, case 1 patient's dysphagia was milder and the response to ballooning was better than the case 2 patient, who had only vagus nerve injury. This difference may be originated from the severity of vagus nerve injury, though we have not conducted electromyography of vagus nerve.

In this report, the possibility of spontaneous recovery cannot be fully excluded. To confirm the ballooning effect and rule out spontaneous recovery, electromyography of vagus nerve should have been performed before and after the procedure. We could not conduct electromyography, as both patients refused from concerns.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on balloon dilatation on cricoesophageal dysfunction by postoperative vagus nerve injury. In this case report, conventional dysphagia therapy did not show good results, but balloon dilatation induced rapid improvements of dysphagia. Considering the effect and safety, videofluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation of UES is thought to be an alternative method for early recovery of UES opening dysfunction by postoperative vagus nerve injury.

References

1. Bhayani MK, MacCracken E, Frim D, Baroody FM. Prolonged cricopharyngeal muscle spasm after resection of the cervical vagus nerve in a 15-year-old. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2008; 44:71–74. PMID: 18097197.

2. Kim JC, Kim JS, Jung JH, Kim YK. The effect of balloon dilatation through video-fluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) in stroke patients with cricopharyngeal dysfunction. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2011; 35:23–26.

3. Hu HT, Shin JH, Kim JH, Park JH, Sung KB, Song HY. Fluoroscopically guided balloon dilation for pharyngoesophageal stricture after radiation therapy in patients with head and neck cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010; 194:1131–1136. PMID: 20308522.

4. Kim DY, Park CI, Ohn SH, Moon JY, Chang WH, Park SW. Botulinum toxin type A for poststroke cricopharyngeal muscle dysfunction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2006; 87:1346–1351. PMID: 17023244.

5. Brouillette D, Martel E, Chen LQ, Duranceau A. Pitfalls and complications of cricopharyngeal myotomy. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1997; 7:457–475. PMID: 9246397.

6. Solt J, Bajor J, Moizs M, Grexa E, Horvath PO. Primary cricopharyngeal dysfunction: treatment with balloon catheter dilatation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001; 54:767–771. PMID: 11726859.

7. Parameswaran MS, Soliman AM. Endoscopic botulinum toxin injection for cricopharyngeal dysphagia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002; 111:871–874. PMID: 12389853.

8. Clary MS, Daniero JJ, Keith SW, Boon MS, Spiegel JR. Efficacy of large-diameter dilatation in cricopharyngeal dysfunction. Laryngoscope. 2011; 121:2521–2525. PMID: 21997884.

9. Dou Z, Zu Y, Wen H, Wan G, Jiang L, Hu Y. The effect of different catheter balloon dilatation modes on cricopharyngeal dysfunction in patients with dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2012; 27:514–520. PMID: 22427310.

Fig. 1

Videofluoroscopic swallow study images of (A) case 1 patient and (B) case 2 patient before (a, b, c) and after (d, e, f ) videofluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation of upper esophageal sphincter (UES). Before ballooning, patients showed UES opening dysfunction (A-a, B-a) followed by aspiration (A-b, B-b), and large residue in pyriform sinus (A-c, B-c). After ballooning, we confirmed UES opening improvement (A-d, B-d) without aspiration (A-e, B-e), and decreased pyriform sinus residue (A-f, B-f).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download