Abstract

Objective

To investigate compliance with a viscosity-modified diet among Korean dysphagic patients and to determine which factors are associated with compliance.

Methods

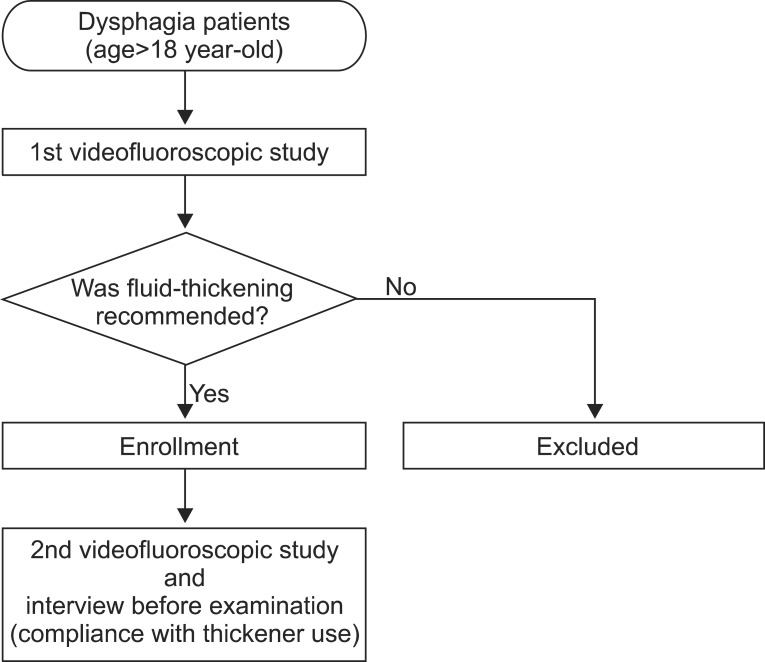

We retrospectively reviewed medical records of patients who had been recommended to use thickeners in the previous videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS). Among 68 patients, 6 were excluded because tube feeding was required due to deterioration in their medical condition. Finally, 62 patients were included in the study. Patient compliance was assessed using their medical records by checking whether he or she had maintained thickener use until the next VFSS. To determine which factors affect compliance, the relationship between thickener use and patient characteristics, such as sex, age, inpatient/outpatient status, severity of dysphagia, aspiration symptoms, follow-up interval of VFSS, and current swallowing therapy status were assessed. For noncompliers, reasons for not using thickeners were investigated by telephone interview.

Results

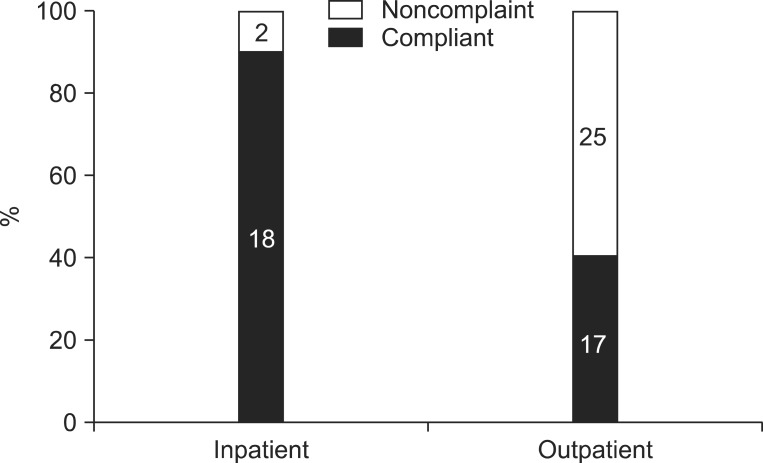

Among 62 patients, 35 (56.5%) were compliers, and 27 (43.5%) were noncompliers. Eighteen (90%) of 20 inpatients had followed previous recommendations; however, only 17 (40.5%) of 42 outpatients had been using thickeners. Of patient characteristics, only admission status was significantly correlated with compliance. When asked about the reason why they had not used thickeners, noncompliers complained about dissatisfaction with texture and taste, greater difficulty in swallowing, and inconvenience of preparing meals.

The term "dysphagia" is applied to all kinds of swallowing difficulties. The condition is clinically common and can be attributed to various diseases including disorders of the central nervous system, such as stroke and traumatic brain injury, neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease, disorders of the peripheral nervous system, neuromuscular junction disorders, myopathies, and local anatomical lesions [1]. Major complications of dysphagia are pneumonia, malnutrition, dehydration, and increased mortality. These complications bring about the increased need of medical resources in terms of the length of hospital stay, rehabilitation time, the need for long-term care assistance, and health care cost [2].

Altering the characteristics of food is one of the common approaches used to treat and compensate dysphagia [3]. Size, color, shape, taste, viscosity, and texture are components of the characteristics of food. In general, thin fluid, such as water, soup, or juice is more likely to be aspirated [4]; therefore, thickening fluid using thickeners is the mainstay of dysphagia diet [5]. One study of 66 dysphagic patients documented that thickened fluid and soft mechanical diet reduced the incidence of pneumonia by 80% compared with a regular diet [6].

Despite these advantages, many patients and caregivers are reluctant to make modifications to the diet. It has been demonstrated that 75% of the patients who were recommended to modify diet with thickeners did not prefer using them [7]. According to a study in the United States, there was a disjunction between the expectations of medical staffs and what patients are really doing. Speech-language pathologists expected a higher compliance of 72%; however, only 36% patients followed their instructions on thickener use [8].

No study has documented, however, the level of compliance with a viscosity-modified diet in Korea. The purposes of the present study were to examine compliance with a viscosity-modified diet among Korean dysphagic patients and to evaluate relevant factors affecting compliance.

A retrospective chart review was performed in Seoul National University Hospital, a university-affiliated tertiary care hospital. From June 1 to September 30, 2011, a total of 349 patients underwent a videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS). We included only those who had been recommended thickener use in fluids in the previous VFSS within 6 months (Fig. 1). Among 349 patients, modified diet including thickened liquids was prescribed in 68 patients. Among those, 6 required nasogastric tube feeding due to the development or deterioration of their medical condition. Finally, 62 dysphagic subjects were included in the analysis.

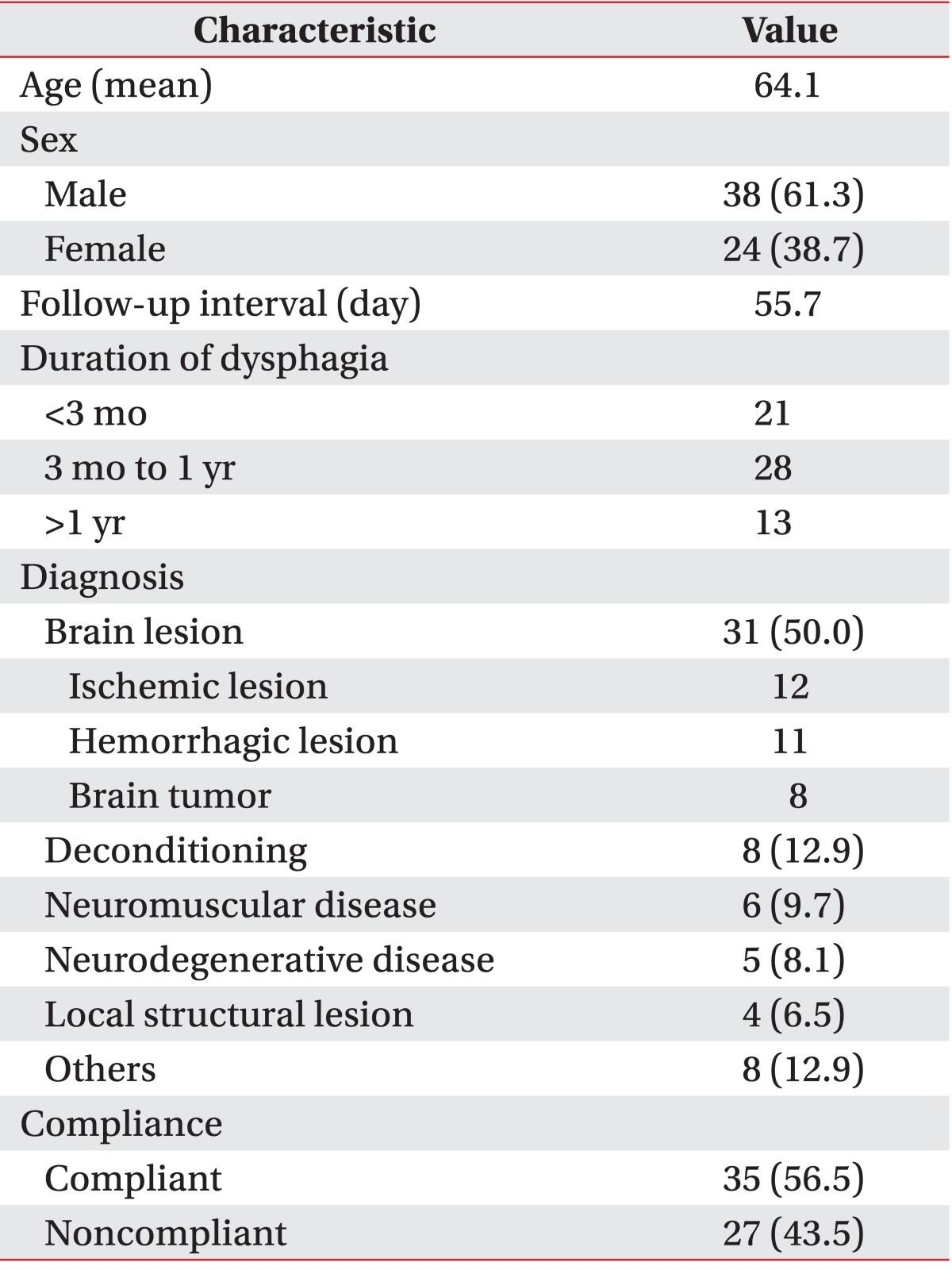

Demographic and clinical data of study subjects are shown in Table 1. The mean age at VFSS was 64.1 years. The mean interval time between the studies was 55.7 days on average, and half of the patients had dysphagia secondary to brain lesion, such as stroke or brain tumor.

Through medical chart review, data on age, sex, diagnosis, admission status (outpatient or inpatient), current diet, recommended diet regimen in the previous VFSS, videofluoroscopic dysphagia scale (VDS) [9], symptoms of aspiration, and current status in swallowing therapy were identified. At our institution, just before the VFSS, all patients or caregivers are routinely asked about the current diet and whether they have maintained the use of thickeners or not. Compliance was defined as using thickeners in liquids, such as water and juice. Accordingly, patients were categorized into two groups: compliant and noncompliant. Furthermore, we analyzed factors affecting compliance among the clinical characteristics of study subjects including sex, age, admission status, prescribed viscosity level, interval between swallowing studies, presence of aspiration symptoms, severity of dysphagia in VDS, and current status of swallowing therapy.

For patients in the noncompliant group, the reasons for cessation of thickener use and, if any, his or her own compensatory maneuvers were assessed by phone interview. For each question, multiple answers were allowed.

All statistical analyses were performed with the PASW Statistics ver. 18 for Windows software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To decide which factors are associated with compliance among patient characteristics, chi-square tests and univariate logistic regression analyses were used for categorical variables and continuous variables, respectively. In multiple logistic regression analysis, variables showing p<0.2 in the univariate analysis were included. For multiple analysis, the stepwise forward procedure was used for variable entry.

Among 62 patients, 35 (56.5%) had been using thickeners in liquids; however, 27 (43.5%) had been drinking thin fluids. Consequently, the overall compliance rate for viscosity modification was 56.5%. Twenty subjects were inpatients at the time of follow-up VFSS, and 18 (90%) of 20 were compliant. On the contrary, among a total of 42 outpatients, 17 (40.5%) were following the recommendations. Thus, the admission status (inpatient or outpatient) proved to be significantly associated with compliance (p=0.001) (Fig. 2). However, compliance was not shown to be significantly correlated with following factors: sex, age, prescribed viscosity level, interval between swallowing studies, presence of aspiration symptoms, and severity of dysphagia in VDS. A trend toward higher compliance in those currently receiving swallowing therapy was observed; however, the difference was insignificant (p=0.108; odds ratio, 2.86). Finally, admission status and current swallowing therapy status were included in the multiple logistic regression model. In the analysis, compliance was shown to be significantly associated with admission status (p=0.004); however, no correlation was found between compliance and current application of swallowing therapy (p=0.532).

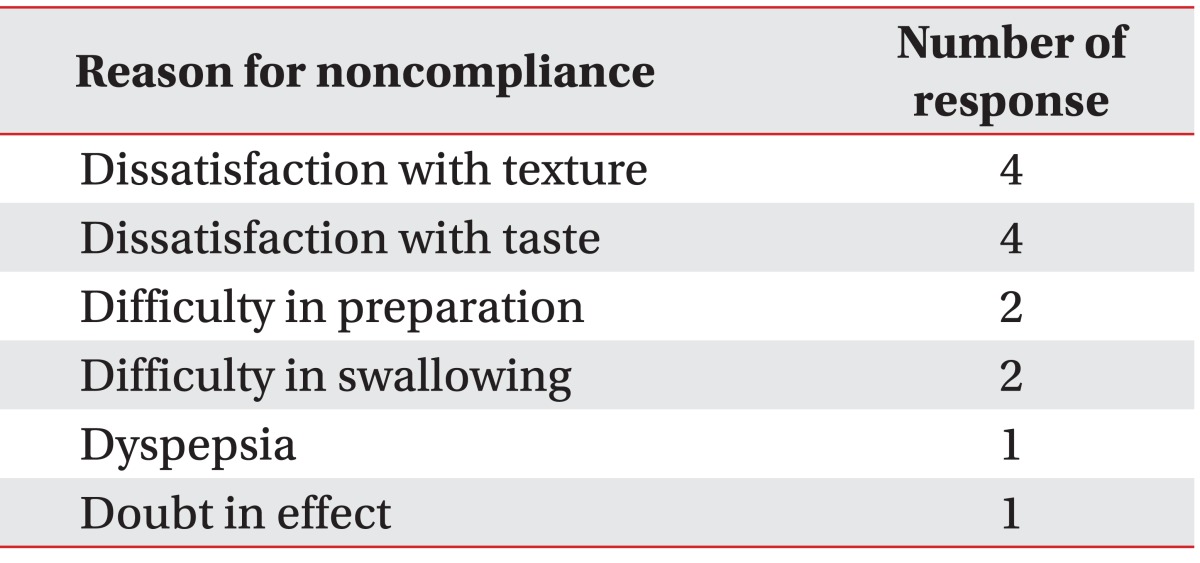

Among the noncompliant, ten patients responded to the interview regarding the reasons for not using thickeners, whereas the others were not available as a result of phone connection failure, no answer, death, etc. Responses included dissatisfaction with texture (4 patients), dissatisfaction with taste (4 patients), difficulty in preparation (2 patients), and greater difficulty in swallowing (2 patients) (Table 2). Concerning compensatory maneuvers, 2 patients answered that they swallow fluids by splitting in small amounts using a straw or a spoon. One patient said, "I eat in the chin-tuck position." Another patient said, "I use glutinous rice flour to thicken fluids rather than commercialized thickeners."

This is the first study demonstrating compliance with a viscosity-modified diet in Korean dysphagic patients. The overall compliance for fluid-thickening was 56.5%, and this finding is in close agreement with those of previous studies from other countries documenting compliance with a dysphagia diet [8,10,11]. According to one study in New Zealand [10], 18 (21%) out of 86 patients with dysphagia were never compliant with fluid-thickeners, whereas the other 68 patients (79%) sometimes or always followed the prescribed dietary regimen. Even though compliance in their study is higher than that of the present study, the difference may arise from the distinct definition of compliance in each study. Another study in the United Kingdom found that 48% of the patients complied with the recommendations of speech and language therapists [11]. In another study in the United States, only 36% maintained thickener use [8]. Compliance in these studies was lower compared to that in the present study. However, these studies were conducted among outpatients. Among outpatients of the present study, we observed markedly similar compliance.

Admission status was the only factor which was proven to be associated with compliance. Other variables including age, sex, aspiration symptoms, and even current swallowing therapy status did not significantly affect compliance. According to the previous studies, however, younger and institutionalized patients were more likely to be noncompliant. In the study, the authors commented that such an unexpected age difference appears to be caused by a survival effect which reflects higher mortality among noncompliant older people. Furthermore, persons who live in community facilities usually do not prepare their meals by themselves, thus leading to higher levels of compliance due to passivity [10]. The results of the present study which demonstrated inpatients' higher compliance correspond with this finding. We expected that patients who maintained swallowing therapy until the follow-up VFSS would be more compliant, and the results were in close agreement with this prediction; however, the difference did not reach statistical significance. This warrants a further study with a larger sample size.

Regarding the reasons for not using thickeners, many patients complained of dissatisfaction with texture and taste (4 patients each). Some patients reported that preparing a dysphagia diet is inconvenient, or reported aggravation of swallowing difficulty with thickener use. According to a previous study concerning noncompliance with swallowing recommendations, dissatisfaction with diet modifications was reported by all participants, followed by open denial, calculated risk, and minimization, in order of frequency [12].

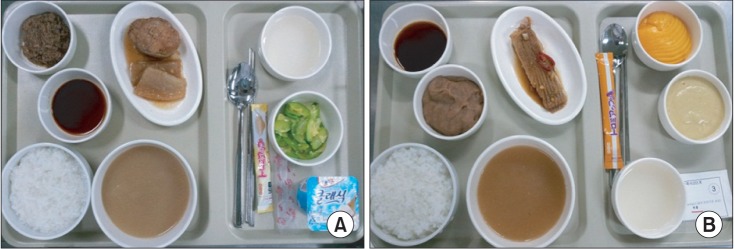

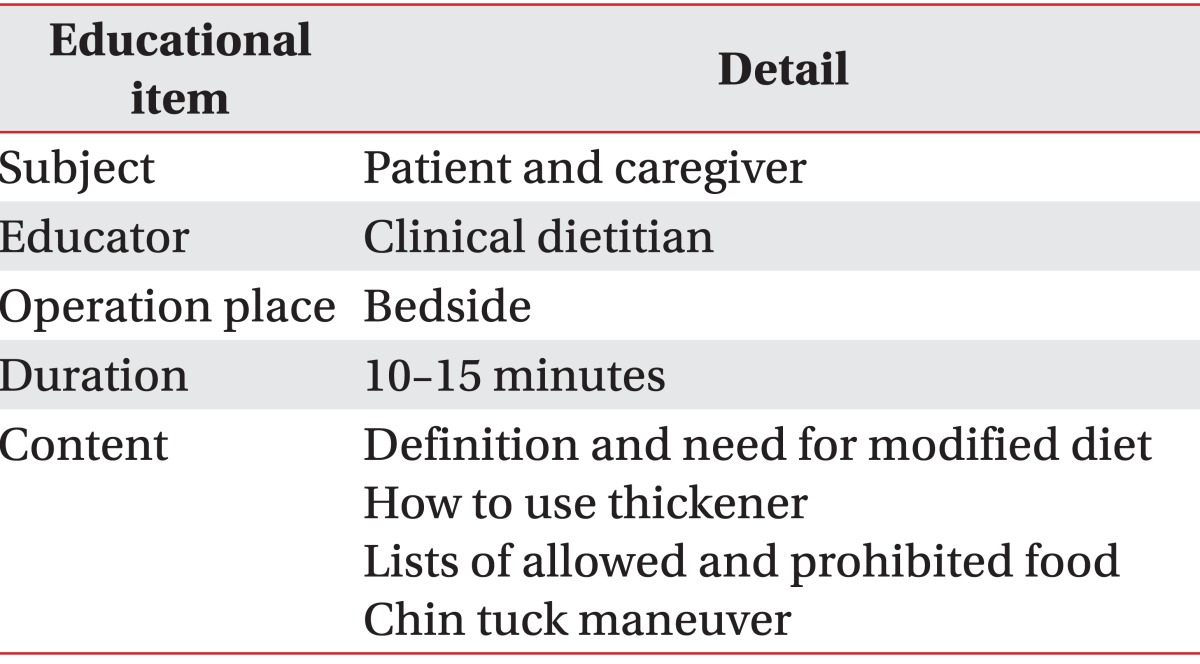

The most commonly used methods to deal with patient noncompliance with diet modifications are education and involvement of others [12]. One intervention study demonstrated a significant improvement in compliance with thickener use (48% to 64%) after having the participants undergo a program based on an in-house training scheme and pre-thickened drinks [11]. In the present study, clinical dietitians provided a structured educational program for all the inpatients and some outpatients (Table 3, Fig. 3). Therefore this may be the reason for the difference in compliance between outpatients and inpatients. The result opens the possibility of further investigations concerning the effects of educational programs on compliance.

This study has important limitations that mostly stem from its small sample size and retrospective design. First, the evaluation of compliance depended on the patients' recollection. Even though we should acknowledge the efficiency of this design since we cannot practically monitor all the patients, there exist possibilities of recall bias, lie and false response. Second, compliance was assessed dichotomously only. In further research, it can be subdivided into many grades. Additionally, utilization of a prospective design in future studies may increase the response rate for the reasons of noncompliance and compensatory maneuvers.

In conclusion, among Korean dysphagic patients, compliance with a viscosity-modified liquid diet was found to be only about 50%. Betterments of texture and taste along with patient education might be necessary to improve compliance with thickener use.

References

1. Olszewski J. Causes, diagnosis and treatment of neurogenic dysphagia as an interdisciplinary clinical problem. Otolaryngol Pol. 2006; 60:491–500. PMID: 17152798.

2. Sura L, Madhavan A, Carnaby G, Crary MA. Dysphagia in the elderly: management and nutritional considerations. Clin Interv Aging. 2012; 7:287–298. PMID: 22956864.

3. Groher ME, McKaig TN. Dysphagia and dietary levels in skilled nursing facilities. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995; 43:528–532. PMID: 7730535.

4. Feinberg MJ, Knebl J, Tully J, Segall L. Aspiration and the elderly. Dysphagia. 1990; 5:61–71. PMID: 2209101.

5. Curran J, Groher ME. Development and dissemination of an aspiration risk reduction diet. Dysphagia. 1990; 5:6–12. PMID: 2202558.

6. Groher ME. Bolus management and aspiration pneumonia in patients with pseudobulbar dysphagia. Dysphagia. 1987; 1:215–216.

7. Macqueen C, Taubert S, Cotter D, Stevens S, Frost G. Which commercial thickening agent do patients prefer? Dysphagia. 2003; 18:46–52. PMID: 12497196.

8. Leiter AE, Windsor J. Compliance of geriatric dysphagic patients with safe-swallowing instructions. J Med Speech Lang Pathol. 1996; 4:289–300.

9. Kim DH, Choi KH, Kim HM, Koo JH, Kim BR, Kim TW, et al. Inter-rater reliability of videofluoroscopic dysphagia scale. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012; 36:791–796. PMID: 23342311.

10. Low J, Wyles C, Wilkinson T, Sainsbury R. The effect of compliance on clinical outcomes for patients with dysphagia on videofluoroscopy. Dysphagia. 2001; 16:123–127. PMID: 11305222.

11. Rosenvinge SK, Starke ID. Improving care for patients with dysphagia. Age Ageing. 2005; 34:587–593. PMID: 16267184.

Fig. 2

Compliance difference between outpatients and inpatients. Outpatients showed lower compliance than inpatients (n=62).

Fig. 3

Examples of modified diet. (A) Liquids with honey-like viscosity and mechanically altered solids. (B) Liquids with nectar-like viscosity and pureed solids.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download