Abstract

Objective

To validate the Motor Impairment Scale (MIS) of the Korean long-term care insurance (LTCI) system by comparing with the service time offered for aiding activities of daily living (ADL) and the ADL score.

Methods

A total of 407 elderly subjects without dementia who had used LTCI services were included in this study. Spearman correlations and multivariate linear regression models were employed to determine the relationship of the upper and lower limb MIS (U-MIS and L-MIS, respectively) to the service time and ADL. Stratified analyses for the facility group (n=121) and the domiciliary group (n=286) were performed.

Results

There were significant differences in characteristics between facility group and domiciliary group. The MIS was significantly correlated with service time in facility group (Spearman p=0.41 for U-MIS, Spearman p=0.40 for L-MIS). After adjusting for age, sex, and cognition score, U-MIS was an independent predictor for service time in facility group (p=0.04). In domiciliary group, no significant correlation was found between the MIS and service time. The MIS correlated with all of the ADL items and total ADL score in both groups. After adjusting for other factors including age, sex, and cognitive score, U-MIS and L-MIS were independent variables for explaining the total ADL score in both groups.

The long-term care insurance (LTCI) system has been implemented in a few countries including Korea, Japan, and Germany [1,2]. The LTCI is a system to improve the quality of life of the elderly and to contribute to the family's welfare by providing care benefits to elderly persons who cannot maintain the activities of daily living (ADL) without assistance [3]. The policy consists of providing social services that complement the care given by families rather than providing alternative medical services. The LTCI in Korea covers senior citizens who are 65 years old or older and those who are less than 65 years old and suffering from geriatric disease [4].

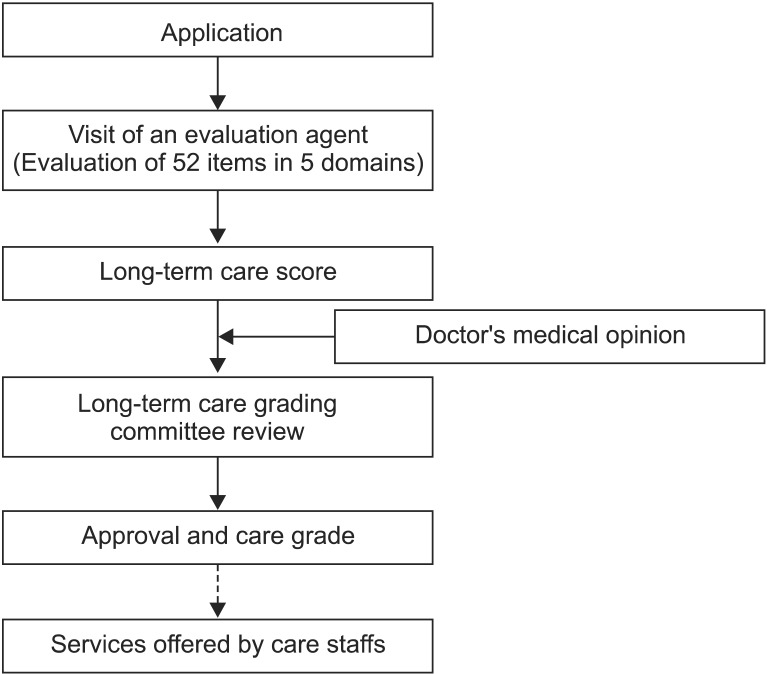

For acceptance into the LTCI program, an evaluation agent, such as a nurse, social worker or physical therapist, visits the home of the person applying for long-term care for evaluation of the condition of the applicant, using 5 evaluation domains [3,5] (Fig. 1). The long-term care grading committee reviews the status of the applicant and doctor's medical opinion to decide the care grade the applicant should receive. The Korean LTCI employs a system of 3 care grades. Elderly people who have to depend on assistance in all aspects of daily life are categorized into care grade 1. Senior citizens who need continuous instruction and monitoring are classified into care grade 2. Lastly, aged persons who need some assistance when going out are categorized into care grade 3.

Since the introduction of the Korean LTCI in 2008, the beneficiaries of this social insurance scheme have numbered up to 323,000 elderly persons in 2012. Because doctors are not able to evaluate all of the applicants, a valid evaluation system with qualified agents is mandatory. To assess the validities of the 5 domains of the evaluation system, the Korea Institute for Health and Social Affairs (KIHASA) collected data on the elderly who had been using long-term care services in the period from August 2011 through September 2011 [5].

The evaluation tool for measuring motor impairment of the rehabilitation domain, named the Motor Impairment Scale (MIS), was introduced and adopted despite insufficient evidence for its validity and reliability. Although the MIS has been used by up to 950,000 applicants since 2008 as part of a motor evaluation tool in LTCI, there have been few reports examining the validity and reliability of the MIS. The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationships of the MIS with service time for ADL, ADL score and care grade by using objective data from the KIHASA. To the best of the authors' knowledge, this is the first study to report the validity of the MIS in the Korean LTCI system.

A total of 23 qualified care institutions of the National Health Insurance Corporation, in which the care grades were evenly distributed, were selected. The data were collected from 1,006 elderly persons from 6 residential medical welfare facilities, 6 domiciliary visit care institutions, 6 day or night protection institutions, and 5 domiciliary nursing institutions. We excluded participants who had been diagnosed with dementia by a doctor to eliminate the effect of cognition on motor ability [6]. Eventually, 407 elderly persons were included in the current study.

Many previous studies on the LTCI system looked separately at the elderly who were admitted to facilities and those who were living in their home because they have quite different characteristics [6-10]. In the current study, the participants who were admitted to a medical welfare facility were allocated to the facility group (FG). The other subjects receiving domiciliary benefits including domiciliary visit care, day or night protection, or domiciliary nursing service were included in the domiciliary group (DG). Among the participants, 121 subjects were using facility benefits, and the rest of the 286 subjects were using domiciliary benefits. Stratified analyses were performed according to the care benefit to verify the validity of the MIS in each subgroup.

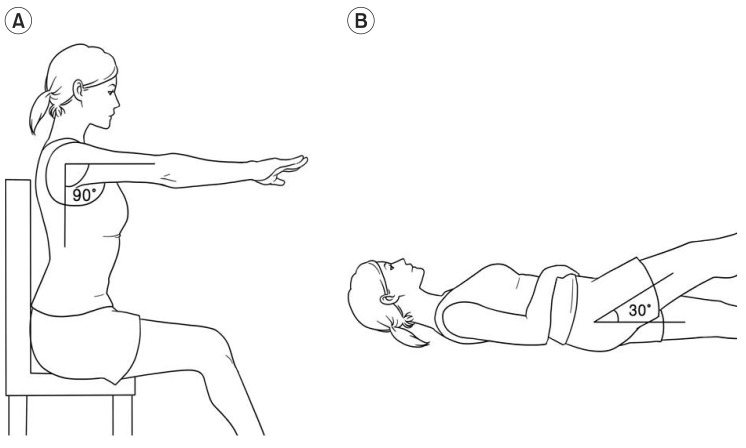

The evaluation items in the LTCI system were recorded by qualified evaluation agents. The evaluation agents recorded age, sex, care grade, vision impairment, and hearing impairment after gathering this information from the participants, caregivers or care staff. Motor impairment was evaluated using the MIS with a 3-grade system by observing the actual movements of the participants, and not just by inquiring about the ability to perform. The MIS was assessed for each of the upper and lower limbs as shown in Fig. 2 (U-MIS and L-MIS, respectively). Each of the upper limbs was assessed by asking the subject to extend the limb and hold it for 10 seconds with 90° of shoulder flexion and the hand in the palm-down position, in the sitting or standing state. For each of the lower limbs, investigators instructed the subject to extend the limb and hold it for 5 seconds with 30° of hip flexion in the supine position. After the limb was placed in the appropriate position, the subject's effort in making the movement was graded on a scale from 0 to 2: normal was 0, partial paralysis was 1, and complete paralysis was 2. A normal (score of 0) was defined as holding the limb for a full 10 seconds for the upper limbs, and a full 5 seconds for the lower limbs. Partial paralysis (score of 1) was defined as making some effort against gravity or drifting down before the full 10 seconds for the upper limbs, and 5 seconds for the lower limbs. Complete paralysis (score of 2) was defined as no movement or no effort against gravity for both of the upper and lower limbs. Each limb was tested in turn, and the scores for the upper limbs were added together to determine the U-MIS. L-MIS was acquired by adding the scores for each lower limb. Each of the U-MIS and L-MIS ranged from 0 to 4 points. A higher MIS score indicated more severe motor impairment.

The evaluation agents observed the participants and care staff for 24 hours to record the types and time of services. The service time was evaluated on a different day to the other evaluations in order to prevent loss of services through the performance of the evaluations. The agents recorded the type of services according to a series of service codes every minute. The minutes taken for each group of services such as ADL, communication, nursing, and welfare were added to generate the service time for each of those services. In the current study, we calculated the service time for ADL by adding the times for hygiene activities, dressing, bathing, urination, defecation, feeding, transfers, and mobility together.

The ADL in LTCI was assessed with 13 items, and 6 of them were consistent with the Korean activities of daily living (K-ADL) items [11]. The 13-item ADL evaluation scale included activities such as dressing, washing one's face, brushing one's teeth, bathing, feeding, transfers, sitting up, mobility in the room, mobility in the facility or house, using the toilet, bowel control, bladder control, and washing one's hair. As with the K-ADL, ADL items in the LTCI were scored using a 1 to 3 grading scale: 1 (independent), 2 (partially dependent), and 3 (totally dependent). Each score of the 13 ADL items were added together to calculate the total ADL score.

Although we included only people without dementia in our study, the cognitive function of the subjects was still considered in the analysis due to the possibility of cognitive state being a confounding factor. Participants were required to answer questions on a total of 11 cognitive items. The items included simple questions to assess memory, calculation, and inference ability. Among them, 7 items overlapped with those of the Korean version of Mini-Mental State Examination (K-MMSE) [12]. One point was given for one correct answer given by the subject, yielding a cognitive score on an 11-point scale. The correctness of the answer such as age and birthday was confirmed by staff members or caregivers.

The estimated service time is one of the most important determinants of eligibility for LTCI in Korea and Japan [5,13]. Additionally, the main purpose of LTCI is to provide care to the elderly who cannot maintain ADL without assistance and to improve the quality of life in those people [14,15]. Therefore, the service time needed for ADL was considered a primary criterion to confirm the validity of the MIS. The correlation between MIS and service time was analyzed to investigate the validity of the MIS. The relationships of MIS with ADL and care grade were also analyzed as supporting evidence for the validity of the MIS.

Independent t-test and chi-square test were used to compare characteristics between FG and DG. The relationships between MIS and service time for ADL were analyzed by Spearman ρ correlation. Multivariate linear regression analysis was employed to identify independent predictors for the service time. Univariate linear regression analyses were performed in advance to examine the association between service time and demographic factors or measurements. A multivariate linear regression analysis was then performed with the enter method using significant variables in the univariate analyses. The relationship between MIS and ADL was also analyzed by Spearman ρ correlation and the multivariate linear regression model. Data were analyzed separately for FG and DG in the analysis. The correlation of care grade with MIS, service time, and total ADL score were analyzed by Spearman ρ correlation in both the subgroups. The significance level for all hypothesis testing was set at p<0.05. SPSS ver. 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical calculations.

The mean age of total participants was 77.27±9.11 years as shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between FG and DG in U-MIS, L-MIS, age, vision impairment, and hearing impairment. FG had a worse ADL score, more service time and a lower cognition score than DG. Females were predominant in both groups, but the proportion of males was relatively higher in DG. The distribution of care grade was different between FG and DG. DG included more independent elderly persons, who were represented as care grade 3. Living alone could be evaluated only in the DG, and 24.48% of the DG had no family members.

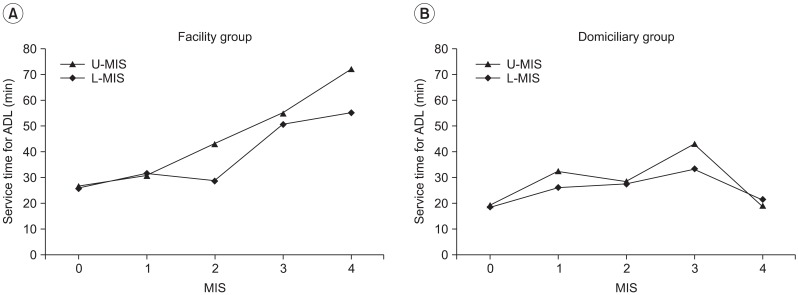

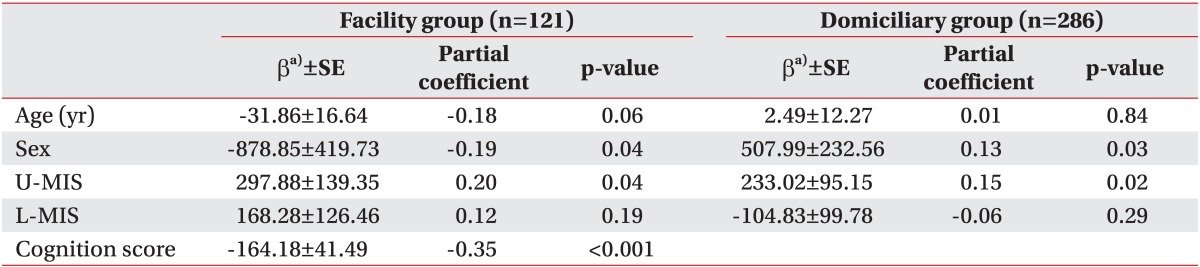

Significant correlation between MIS and service time was observed only in FG (Spearman ρ=0.41, p<0.001 for U-MIS; Spearman ρ=0.40, p<0.001 for L-MIS), but not in DG (Fig. 3). In the univariate analysis, age, sex, U-MIS, L-MIS, and cognition score had significant associations with service time in FG. For DG, only sex and U-MIS showed significant association with service time. The results of the multivariate analysis for both groups are shown in Table 2. In the FG, the predictability of age, sex, U-MIS, L-MIS, and cognition score was one third of the service time variability (adjusted R2=0.33, p<0.001). After adjusting for age, sex, and cognition score, U-MIS was significantly associated with service time. L-MIS, however, was no longer an independent predictor for service time after adjustment of other factors. In DG, age, sex, U-MIS, and L-MIS were able to predict only 2.4% of the variability of service time (p=0.03). After adjustment for other predictors, U-MIS showed a weak positive correlation with service time.

The U-MIS and L-MIS showed significant correlation with most of the ADL items and the total ADL score (Table 3). In FG, all of the 13 items and the total ADL score displayed moderate correlation with U-MIS and L-MIS. However, in DG, bathing, bowel control, bladder control, and washing one's hair showed weaker correlation with U-MIS. Dressing, bathing, and bladder control showed weaker correlation with L-MIS. In the univariate analysis, U-MIS, L-MIS, and cognition score showed significant association with the total ADL score in FG. For DG, U-MIS, L-MIS, cognition score, vision impairment, and living alone were significantly associated with the total ADL score. Final multivariate models for the total ADL score in both groups are shown in Table 4. In the multivariate model of FG, the predictive value of age, sex, U-MIS, L-MIS, and cognition score was more than half of the total ADL score variability (adjusted R2=0.56, p<0.001). After adjusting for age, sex, and cognition score, U-MIS and L-MIS were significantly associated with the total ADL score. In DG, age, sex, U-MIS, L-MIS, cognition score, vision impairment, and living alone were able to predict 34.4% of the variability of the total ADL score (p<0.001). After adjustment for other predictors, U-MIS and L-MIS were still positive independent variables for the total ADL score.

It was demonstrated that care grade was significantly correlated with service time, total ADL score, U-MIS and L-MIS (p=-0.65, p=-0.77, p=-0.44, and p=-0.47, respectively) in FG. In DG, the correlations of care grade with total ADL score, U-MIS and L-MIS were weaker than in FG (p=-0.64, p=-0.27, and p=-0.35, respectively). We failed to prove any correlation between service time offered for ADL and care grade in DG.

There have been many studies concerning the adequacy of evaluation items in the LTCI in accurately assessing the care needs of the elderly [16-19]. However, the studies on the validity and reliability of the evaluation tools in the LTCI system have been rather limited up until now [20,21]. A study revealed that care grade and cognitive impairment were generally correlated, but some adjustment measure for cognitive impairment was needed in mildly or moderately physically disabled patients [6]. Another study reported that physical function classified by the LTCI system of Japan was correlated with Fried's criteria for frailty syndrome [22].

In the process of long-term care grade judgment, an evaluation agent assesses the applicant according to the 5 domains of physical functions, which include cognition, behavioral changes, demand for nursing, and demand for rehabilitation. Among the 5 domains, the rehabilitation domain consists of MIS and joint range of motion limitation. The present study was designed to investigate the validity of the MIS in the LTCI system of Korea. The service time offered for ADL was considered a primary criterion measurement to verify the concurrent validity of the MIS because the payments of LTCI are based on the estimated service time. The ADL evaluations were used as a secondary criterion measurement and not as a primary criterion measurement because the validities of ADL items and score are still unproven. Care grade was used only as a supportive criterion measurement, since it had been assigned before this study. We considered the possibility that the applicants might give false information to the evaluation agents to obtain a higher care grade. The objective of the current study was achieved by demonstrating a significant correlation between MIS and service time for ADL and ADL evaluations.

The characteristics of FG and DG were quite different, resulting in different patterns of correlations. The total ADL score, cognition score, service time, and sex of FG and DG were significantly different. The distribution of care grade was dissimilar between FG and DG, and care grade 3 comprised a larger proportion in DG. The elderly in FG showed significantly more dependent ADL and lower cognition scores than those in DG, suggesting more disability among the elderly in FG. Care staff members spent more time on ADL in FG than in DG. The mean age of total participants was approximately equal to the life expectancy of Korean males (77.2 years in 2010), but lower than that of females (84.1 years in 2010). We inferred that the predominance of females in both groups was caused by the longer life expectancy of women [23]. Because there was no statistical difference of MIS between FG and DG, the baseline differences of service time and total ADL score between both groups were assumed to have originated from other factors, such as cognition-related factors or medical disease [8].

Service time for ADL was our primary criterion measurement to gauge the concurrent validity of MIS, because the estimated care time is an important determinant of care need and care grade in Korea and Japan [5,13]. In FG, significant correlation was observed between MIS and service time. U-MIS was an independent predictor after adjusting for age, sex, and cognition score in FG. After adjustment for other factors, L-MIS was not an independent predictor for service time. The motor function of the upper limbs may have more influence on the performance of ADL activities than that of lower limbs. The correlation between MIS and service time in DG was different from our prediction. No relationship between MIS and service time was demonstrated in DG, and only 2.4% of the variation in service time could be explained by age, sex, U-MIS, and L-MIS. Considering these results, our postulation that the service time offered for aiding ADL might be representative of the care needs can be applicable to FG only.

ADL was a secondary criterion measurement to demonstrate the validity of MIS. It was proved that the MIS was correlated with all of the ADL items and the total ADL score. Most of those correlations were moderate except for the weak association of MIS and bathing and bladder control in DG. FG showed stronger correlation between MIS and ADL than DG. After adjustment of age, sex, and cognitive score, U-MIS and L-MIS were independent predictors for the total ADL score in both groups. In conclusion, as the motor functions of the elderly subjects were more impaired, the ADL of these subjects were more dependent. In addition, living alone was another independent predictor for the total ADL score in DG. The elderly subjects who lived alone led a more independent daily life.

The relationships of care grade with MIS, service time, and total ADL score were analyzed to find characteristics of service time in DG, because no correlation was found between MIS and service time. Significant correlations between care grade and MIS, service time, and ADL were demonstrated in FG. In DG, care grade showed a weaker correlation with MIS and total ADL score than in FG. There was no correlation between care grade and service time for ADL. Service time of DG showed no correlation with any of the other variables including MIS and total ADL score. Therefore, service time offered for ADL cannot be used to estimate the ADL and care grade in DG.

A possible explanation for this finding is that the service offered by staff members in DG may not be related to the ADL. There is research showing that the use of major services in domiciliary elderly care was decided more by the needs of the caregivers than by the care grades of the applicants, suggesting that consideration of the caregiver situation should be included in policy making [24]. It is obvious that the services offered by care staff members should be varied, considering the diverse life environments of domiciliary senior citizens. The services can be social such as communication and even just supportive conversation, or related with instrumental ADL such as shopping and banking rather than ADL. In these situations, the care staff members offer special services, while the caregivers help with daily activities. Further research to reveal the service types that the caregivers need in reality are required. A more upgraded system which incorporates individual home environments and provides more suitable services on a case by case basis should be introduced.

Some researchers have sought to develop a simple method of estimation using the ADL category to predict care grade [10]. The accuracy rate for the estimation of care grade by care after urination, walking and eating was 66.7% in the physically disabled facility-care elderly. The current study proved that the MIS was an independent predictor for the service time and the total ADL score. The importance of MIS as an evaluation tool comes from its objective nature compared to the evaluation tools of other domains including ADL and cognition. When the applicants are evaluated by agents, most of the domains are assessed by interviewing the applicants themselves and their caregivers. The domain for rehabilitation demands, composed of motor impairment and joint limitation, is crucial for objective evaluation because it is the only domain in which the agents observe the actual performance of the applicants. Accordingly, in the cases that the caregivers are not cooperative enough to be interviewed or complete the questionnaire, we can estimate the ADL level by simply assessing the motor impairment and cognition score of the elderly. In addition, some malingerers who describe their status as worse than it is can be detected during motor evaluation if they have good cognitive function.

The main limitation of the current study is the exclusion of dementia patients. It has been found that patients with dementia and diseases of the circulatory system, especially cerebrovascular disease, are the most common recipients of care in the LTCI system [1]. The current study can only be applied to the physically disabled elderly because dementia patients were excluded in the study design. Therefore, there is no validity evidence for the other major group of recipients, dementia patients. Further research investigating the validity of MIS in the elderly with dementia is necessary. In addition, because only the criterion validity was proved in the present study, future studies are required to ascertain the reliability of MIS as a useful tool in LTCI.

In conclusion, we found that the MIS had significant validity in predicting service time and ADL in the elderly admitted to a facility. The validity of the MIS was only partially proved in the domiciliary elderly because MIS correlated only with ADL and not with service time for ADL in these participants. Its short measurement time, the ease of learning by evaluation agents, and the correlation with service time and ADL makes the MIS a useful evaluation tool in the LTCI system of Korea. Future studies on the validity of the MIS in dementia patients as well as studies on the reliability of the MIS are necessary.

References

1. Onishi K. Main medical conditions of frail elderly patients that require intensive care under the Japanese Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI) system: a comparison with German LTCI. Jpn Hosp. 2011; 30:77–83. PMID: 21879591.

2. Houde SC, Gautam R, Kai I. Long-term care insurance in Japan: implications for U.S. long-term care policy. J Gerontol Nurs. 2007; 33:7–13. PMID: 17305264.

3. Seok JE. Public long-term care insurance for the elderly in Korea: design, characteristics, and tasks. Soc Work Public Health. 2010; 25:185–209. PMID: 20391261.

4. Kim SH, Kim DH, Kim WS. Long-term care needs of the elderly in Korea and elderly long-term care insurance. Soc Work Public Health. 2010; 25:176–184. PMID: 20391260.

5. Lee YG, Kim CW, Son CG, Sun WD, Jung KH, Lim JG, et al. A study on the reorganization of long-term care insurance care class judging criteria. Seoul: National Health Insurance Service;2012. Report no. Policy-2012-02.

6. Ito H, Tachimori H, Miyamoto Y, Morimura Y. Are the care levels of people with dementia correctly assessed for eligibility of the Japanese long-term care insurance? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001; 16:1078–1084. PMID: 11746654.

7. Campbell AJ, Bunyan D, Shelton EJ, Caradoc-Davies T. Changes in levels of dependency and predictors of mortality in elderly people in institutional care in Dunedin. N Z Med J. 1986; 99:507–509. PMID: 3090485.

8. Wang J, Chang LH, Eberly LE, Virnig BA, Kane RL. Cognition moderates the relationship between facility characteristics, personal impairments, and nursing home residents' activities of daily living. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010; 58:2275–2283. PMID: 21087221.

9. Teitelbaum L, Ginsburg ML, Hopkins RW. Cognitive and behavioural impairment among elderly people in institutions providing different levels of care. CMAJ. 1991; 144:169–173. PMID: 1986829.

10. Sakai Y, Mori S, Nakajima K. Development of a tree model that allows simple estimation of the required care level using the items of the basic investigation of long-term care insurance. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2002; 39:537–544. PMID: 12404751.

11. Won CW, Rho YG, Kim SY, Cho BR, Lee YS. The validity and reliability of Korean activities of daily living (K-ADL) scale. J Korean Geriatr Soc. 2002; 6:98–106.

12. Kwon YC, Park JH. Korean version of mini-mental state examination (MMSE-K) part I: development of the test for the elderly. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1989; 28:125–135.

13. Tsutsui T, Muramatsu N. Care-needs certification in the long-term care insurance system of Japan. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005; 53:522–527. PMID: 15743300.

14. Kim HS, Bae NK, Kwon IS, Cho YC. Relationship between status of physical and mental function and quality of life among the elderly people admitted from long-term care insurance. J Prev Med Public Health. 2010; 43:319–329. PMID: 20689358.

15. Imahashi K, Kawagoe M, Eto F, Haga N. Clinical status and dependency of the elderly requiring long-term care in Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2007; 212:229–238. PMID: 17592210.

16. Shinkai S, Watanabe N, Yoshida H, Fujiwara Y, Amano H, Lee S, et al. Research on screening for frailty: development of "the Kaigo-Yobo Checklist". Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2010; 57:345–354. PMID: 20666121.

17. Tomata Y, Hozawa A, Ohmori-Matsuda K, Nagai M, Sugawara Y, Nitta A, et al. Validation of the Kihon Checklist for predicting the risk of 1-year incident long-term care insurance certification: the Ohsaki Cohort 2006 Study. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2011; 58:3–13. PMID: 21409818.

18. Hirai H, Kondo K, Ojima T, Murata C. Examination of risk factors for onset of certification of long-term care insurance in community-dwelling older people: AGES project 3-year follow-up study. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2009; 56:501–512. PMID: 19827611.

19. Goodlin S, Boult C, Bubolz T, Chiang L. Who will need long-term care? Creation and validation of an instrument that identifies older people at risk. Dis Manag. 2004; 7:267–274. PMID: 15671784.

20. Resnick B, Galik E. The reliability and validity of the physical activity survey in long-term care. J Aging Phys Act. 2007; 15:439–458. PMID: 18048947.

21. Glick OJ, Swanson EA. Motor performance correlates of functional dependence in long-term care residents. Nurs Res. 1995; 44:4–8. PMID: 7862544.

22. Nemoto M, Yabushita N, Kim MJ, Matsuo T, Seino S, Tanaka K. Assessment of vulnerable older adults' physical function according to the Japanese long-term care insurance (LTCI) system and Fried's criteria for frailty syndrome. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012; 55:385–391. PMID: 22100110.

23. Yang S, Khang YH, Chun H, Harper S, Lynch J. The changing gender differences in life expectancy in Korea 1970-2005. Soc Sci Med. 2012; 75:1280–1287. PMID: 22739261.

24. Tamiya N, Yamaoka K, Yano E. Use of home health services covered by new public long-term care insurance in Japan: impact of the presence and kinship of family caregivers. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002; 14:295–303. PMID: 12201188.

Fig. 1

The process for approval in the long-term care insurance system. After submission of the application form to the National Health Insurance Corporation, an evaluation agent visits the applicant to evaluate status in 5 domains. A long-term care score is calculated based on the agent's reports. Finally, a long-term care grading committee reviews all the results including the long-term care score and the doctor's medical opinion to decide the care grade.

Fig. 2

The positions to evaluate the Motor Impairment Scale in long-term care insurance for upper limbs (A) and lower limbs (B). Each upper limb was assessed by asking the subject to extend the limb and hold it for 10 seconds with 90° of shoulder flexion and hand in palm-down position in the sitting or standing state. For each of the lower limbs, investigators instructed the elderly to extend the limb and hold it for 5 seconds with 30° of hip flexion in the supine position.

Fig. 3

Correlations between Motor Impairment Scale (MIS) and service time for activities of daily living (ADL) in facility group (A) and domiciliary group (B). The service time for ADL increased linearly with an increase in upper limb MIS (U-MIS) and lower limb MIS (L-MIS) in facility group. In domiciliary group, no linear correlation was found between MIS and service time for ADL.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download