Abstract

Objective

To determine the clinical characteristics and videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) findings in infants with suspected dysphagia and compare the clinical characteristics and VFSS findings between full-term and preterm infants.

Methods

A total of 107 infants (67 full-term and 40 preterm) with suspected dysphagia who were referred for VFSS at a tertiary university hospital were enrolled in this retrospective study. Clinical characteristics and VFSS findings were reviewed by a physiatrist and an experienced speech-language pathologist. The association between the reasons of referral for VFSS and VFSS findings were analyzed.

Results

Mean gestational age was 35.1±5.3 weeks, and mean birth weight was 2,381±1,026 g. The most common reason for VFSS referral was 'poor sucking' in full-term infants and 'desaturation' in preterm infants. The most common associated medical condition was 'congenital heart disease' in full-term infants and 'bronchopulmonary dysplasia' in preterm infants. Aspiration was observed in 42 infants (39.3%) and coughing was the only clinical predictor of aspiration in VFSS. However, 34 of 42 infants (81.0%) who showed aspiration exhibited silent aspiration during VFSS. There were no significant differences in the VFSS findings between the full-term and preterm infants except for 'decreased sustained sucking.'

Conclusion

There are some differences in the clinical manifestations and VFSS findings between full-term and preterm infants with suspected dysphagia. The present findings provide a better understanding of these differences and can help clarify the different pathophysiologic mechanisms of dysphagia in infants.

Go to :

The development of swallowing functions begins in the fetal period. Non-nutritive sucking begins at 15 weeks' gestation and consistent swallowing is observed at 22-24 weeks of gestation [1]. Sucking-swallowing coordination is usually established by 32-34 weeks of gestation and sucking-swallowing-breathing coordination is consistent by 37 weeks' gestation [2]. Life-threatening neonatal diseases such as premature birth, cardiopulmonary diseases, and neurologic disorders are the major causes of dysphagia. There has been a recent increase in infant swallowing disorders as a result of the improved survival rates noted in infants born prematurely or with life-threatening medical disorders [3]. Furthermore, negative experiences related to feeding, such as intubation, tube feeding, or airway suctioning may further disturb sucking and swallowing development [4].

However, very few studies have investigated the clinical features and mechanisms of dysphagia in infants younger than 1 year. In particular, studies using videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) are limited. Newman et al. [3] performed a retrospective study on 43 infants younger than 1 year using VFSS; of them, laryngeal penetration and aspiration were observed in 17 (40%) and 9 (21%) infants, respectively. Among the infants with aspiration, 88.9% showed silent aspiration. Mercado-Deane et al. [5] performed an upper-gastrointestinal study of 1,003 infants younger than 1 year with vomiting and respiratory symptoms in order to assess the incidence of swallowing dysfunction. They reported the prevalence of swallowing abnormality was high in preterm infants as well as in infants with underlying conditions such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia, congenital heart disease, esophageal atresia and/or tracheoesophageal fistula, and neurologic disorders. In addition, they observed laryngeal penetration and aspiration in 33 (18.5%) and 93 (52.2%) cases, respectively, out of 178 cases in which VFSS was performed. Lee et al. [6] analyzed the VFSS results of 41 extremely-low-birth-weight infants (birth weight <1,500 g) who showed significant desaturation during feeding at ≥35 weeks' gestational age. They observed bronchopulmonary dysplasia and stage 3 or 4 intraventricular hemorrhage in 21 (51.2%) and 3 (7.3%) infants, respectively. In addition, aspiration was observed in 7 (17.1%) infants. Moreover, Kim et al. [7] compared VFSS findings between subjects with and without pneumonia among 38 infants without any associated medial disease who presented with aspiration symptoms: laryngeal penetration and aspiration were observed in 45% and 26% of the infants, respectively. Furthermore, both findings were significantly higher in infants with pneumonia than those without pneumonia. However, no study has compared the VFSS findings of full-term and preterm infants.

Therefore, this study analyzed the clinical features and VFSS findings of infants younger than 1 year with dysphagia and compared the clinical features and VFSS findings of full-term and preterm infants.

Go to :

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Samsung Medical Center, a tertiary medical center in Seoul, Republic of Korea. A waiver of consent was granted for a chart review without patient contact. Included in the study were 107 infants younger than 1 year with dysphagia who underwent VFSS between March 2010 and March 2011. When infants underwent VFSS more than once during the study period, only the first VFSS findings were analyzed.

Clinical characteristics including sex, gestational age at birth, birth weights, corrected age when the VFSS was performed, height and weight were examined. Chief complaints for which the VFSS was requested and medical conditions associated with dysphagia were also collected.

VFSSs were conducted as described by Logemann [8] with some modifications. To evaluate infants, the fluoroscope table was tilted vertically and a feeder seat was placed on the ledge in a semi-reclined position at approximately 45°. Careful attention was paid to the stability of the positioning of the infant on the chair or footplate. Images of the swallowing process were taken in the lateral view (and occasionally in the anteroposterior view) using fluoroscopic equipment Shimavision 3200 HG (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). In infants who were fed only milk, VFSSs were performed with bottle-feeding by mixing an undiluted liquid barium solution, barium sulfate; Solotop sol 140 (Taejoon Pharm, Seoul, Korea) into the milk. The infants' own bottles and nipples were used. Infants who received weaning food were induced to swallow milk first, followed by ground apples and porridge, in order of precedence by bottle-feeding and spoon-feeding. This was performed as quickly as possible in order to minimize radiation exposure. The results were interpreted by a physiatrist and an experienced speech-language pathologist. These investigations were performed to determine any problems in the following oral and pharyngeal phases: 1) sucking patterns, 2) delayed swallowing reflex, 3) the degrees of epiglottic inversion and laryngeal closure, 4) the presence of residues, 5) the presence of penetration, and 6) the presence of aspiration. Decreased sustained sucking was defined when the infant was unable to engage in long sucking bursts (i.e., more than 5 sucks) without cardiorespiratory compromise or any stress sign. Delayed swallowing reflex was defined as when the swallowing reflex did not occur until the contrast material passed the epiglottic vallecula. Epiglottic inversion was judged to be insufficient if it did not completely invert the larynx. Laryngeal closure was judged to be insufficient if the airway was not completely closed during swallowing. Residue was defined as contrast material remaining in the pharyngeal cavity after swallowing. Penetration was defined as when the contrast material passed above the true vocal cord but not below it. Aspiration was defined as when the contrast material passed below the true vocal cord.

The Mann-Whitney U-test was conducted to determine significant differences with respect to demographic characteristics, associated medical conditions, reasons of referral for VFSS, and VFSS findings between the full-term and preterm infants. The χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were conducted to examine the association between the reasons of referral for VFSS and VFSS findings. The level of significance was set at p<0.05. All analyses were performed using SPSS ver. 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Go to :

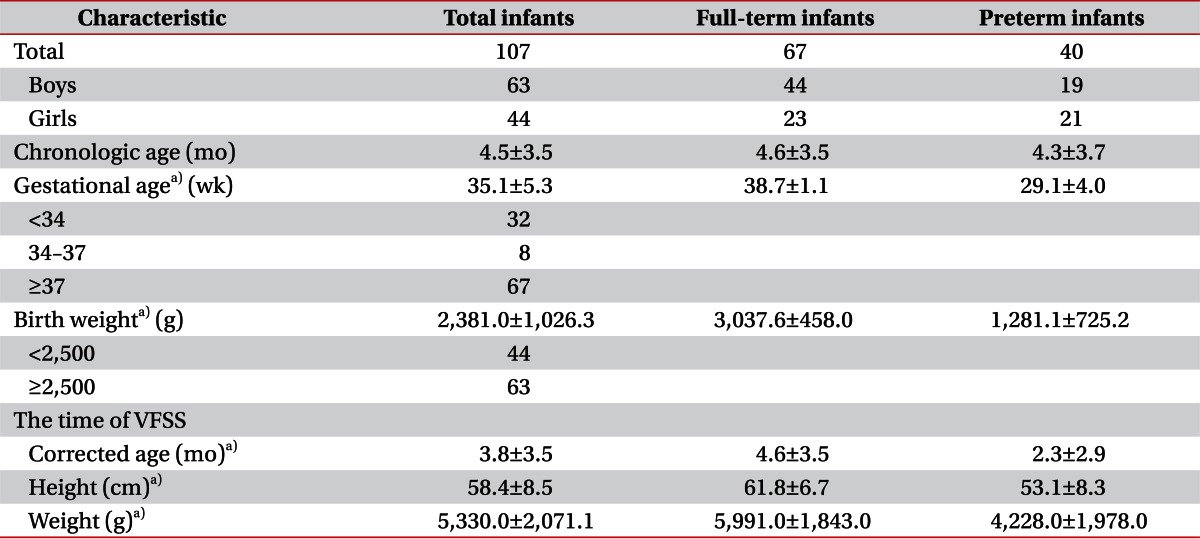

Of the 107 infants, 63 were boys and 44 were girls. The mean gestational age was 35.1±5.3 weeks. Sixty-seven (62.6%) were full-term infants born at 37 weeks or later, and 40 (37.4%) were preterm infants born earlier than 37 weeks. Thirty-two (29.9%) infants were born earlier than 34 weeks and consequently required steroid administration to prevent respiratory distress syndrome. The mean birth weight was 2,381.0±1,026.3 g and 41.1% of infants had low birth weight (i.e., <2,500 g). The mean corrected age at the time of VFSS was 3.8±3.5 months, mean height was 58.4±8.5 cm and mean weight was 5,330.0±2,071.1 g. When the full-term and preterm infants were compared, significant differences were noted in birth weight as well as corrected age, height, and weight at the time of VFSS (Table 1).

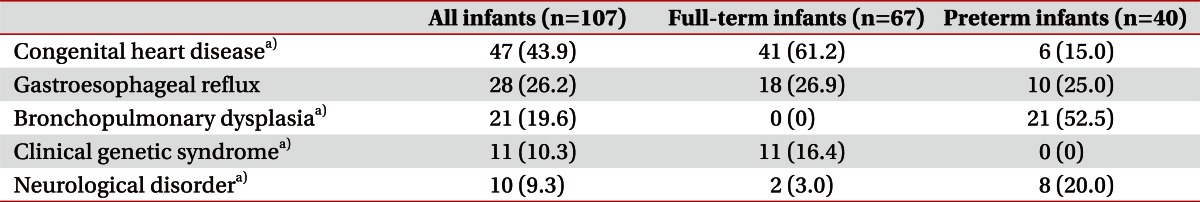

Congenital heart diseases, gastroesophageal reflux, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, clinical genetic syndromes, and neurologic disorders were observed in 47 (43.9%), 28 (26.2%), 21 (19.6%), 11 (10.3%), and 10 (9.3%) infants, respectively. In 15 (14.0%) infants, no particular underlying medical conditions that would cause dysphagia were noted. Except gastroesophageal reflux, there were significant differences in the frequencies between the full-term and preterm infants. Congenital heart disease and clinical genetic syndromes were observed more frequently in full-term infants. Moreover, bronchopulmonary dysplasias and neurologic disorders such as intraventricular hemorrhage were observed more frequently in preterm infants (Table 2).

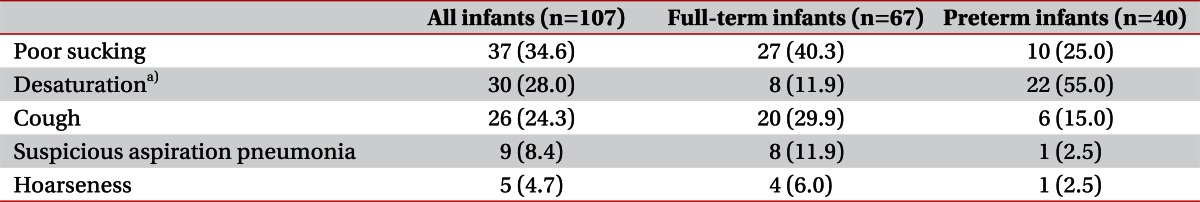

Among the reasons for referral for VFSS, 'poor sucking' was the most common in 37 cases (34.6%), followed by significant 'desaturation' during feeding in 30 cases (28%), 'coughing' during feeding in 26 cases (24.3%), 'suspected aspiration pneumonia' in 9 cases (8.4%), and 'hoarseness' in 5 cases (4.7%). 'Poor sucking' was the most common reason for VFSS in the full-term infants (40.3%), and significant 'desaturation' during feeding was most common reason for VFSS in the preterm infants (55.0%). 'Desaturation' complaints differed significantly between the 2 groups (Table 3).

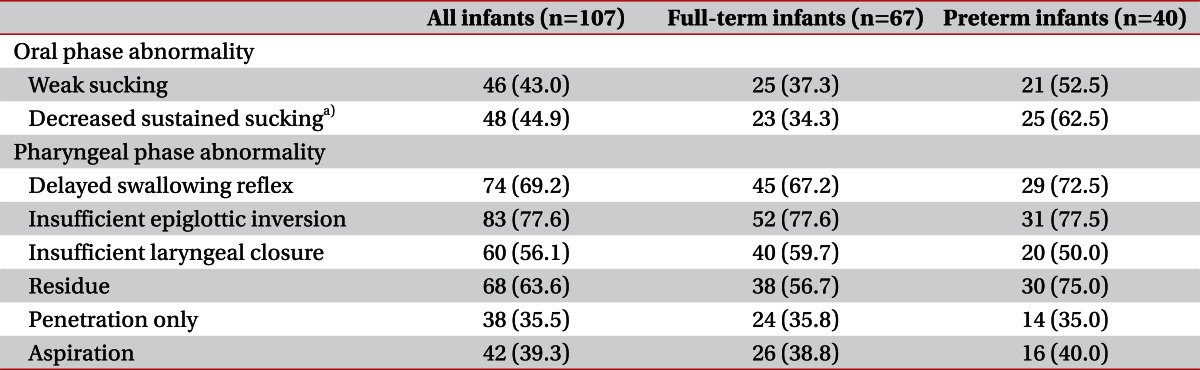

VFSS findings revealed 'weak sucking' and 'decreased sustained sucking' in 46 (43.0%) and 48 (44.9%) infants, respectively, in the oral phase. In the pharyngeal phase, 'delayed swallowing reflex,' 'insufficient epiglottic inversion,' and 'insufficient laryngeal closure' were observed in 74 (69.2%), 83 (77.6%), and 60 (56.1%) infants, respectively. 'Residue,' 'penetration only,' and 'aspiration' were observed in 68 (63.6%), 38 (35.5%), and 42 (39.3%) infants, respectively. Of the 42 infants who showed aspiration, 34 (81.0%) had silent aspiration and aspiration occurred without any symptoms in most cases (Table 4). When comparing the VFSS findings between the full-term and preterm infants, only 'decreased sustained sucking' was significantly different (34.3% and 62.5%, respectively). No significant differences were observed with respect to other VFSS findings between the 2 groups (Table 4).

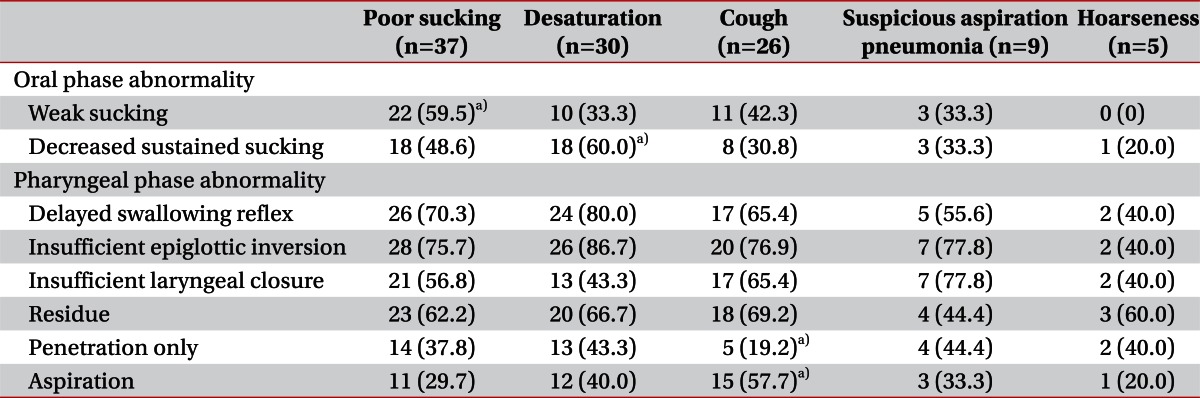

As mentioned above, the χ2 test and Fisher's exact test were conducted to determine the associations between reasons for referral for VFSS as well as VFSS findings for oral- and pharyngeal-phase abnormalities. Cases exhibiting 'poor sucking' were significantly associated with 'weak sucking' in VFSS. Cases exhibiting 'desaturation' were significantly associated with 'deceased sustained sucking' in VFSS. In infants with 'coughing,' 'aspiration' was significantly higher than those without coughing (Table 5).

Go to :

In this study, the mechanism of dysphagia was systematically analyzed using VFSS in a large number of infants younger than 1 year who presented with dysphagia. The present results help describe the symptoms, associated medical conditions, and pathophysiology of dysphagia in infants younger than 1 year.

VFSSs were requested to evaluate oral-phase abnormalities such as 'poor sucking' in 40.3% of full-term infants. Moreover, pharyngeal-phase abnormalities such as 'desaturation,' 'suspected aspiration pneumonia,' 'coughing,' and 'hoarseness' accounted for 75% of all reasons for VFSS in the preterm infants. The reason for this is likely because VFSSs were mostly requested within 3 months (mean±standard deviation, 2.3±2.9 months) when reflexive sucking is still maintained.

In this study, aspiration was observed in 39.3% of infants with dysphagia. Lee et al. [6] and Newman et al. [3] report the 'aspiration' rate of infants to be 17.1% and 21%, respectively, lower than that in the present study. In contrast, Mercado-Deane et al. [5] report the 'aspiration' rate to be 52.2%, higher than the present study. The discrepancies between studies are assumed to be due to differences in subject inclusion criteria, gestational age, medical conditions, test methods, etc. Therefore, additional studies on VFSS findings from individual medical conditions are required.

In this study, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of aspiration between the full-term and preterm infants (38.8% vs. 40.0%, respectively). The only parameter that differed significantly between the full-term and preterm infants in VFSS was 'decreased sustained sucking,' which was significantly higher in preterm infants. Sequential and rhythmic sucking, swallowing, and breathing are controlled by the central nervous system [9,10]. At 34 weeks, the coordination of sucking, swallowing, and breathing is possible because of myelination of the medulla. A mature sucking pattern develops at approximately 35-36 weeks' gestation. However, a well-coordinated pattern may not be established until after 37 weeks' gestation [10]. A mature sucking pattern is characterized by prolonged bursts of more than 10 sucks with a suck-swallow-breathe ratio of 1:1:1 at term. Although the numbers of sucking bursts and suckings per burst increase from 34 weeks to term [11], extremely preterm infants (born at 24-29 weeks' gestation) generate significantly fewer bursts and suckings per burst than more mature preterm infants (born at 30-32 weeks' gestation) when sucking patterns were analyzed at a corrected age of 40 weeks [12]. The extremely preterm infants also exhibited significantly fewer suckings per burst than the full-term infants [12]. This developmental delay of sucking in preterm infants and the fact that the preterm infants' corrected ages at the time of VFSS were significantly lower than those of the full-term infants are the likely underlying causes of the significantly more frequent 'decreased sustained sucking' observed in the preterm infants.

In this retrospective study, cases in which the symptom was 'poor sucking' were significantly associated with 'weak sucking' in the VFSS findings but not with 'decreased sustained sucking.' Moreover, cases in which the symptom was 'desaturation' were significantly associated with 'decreased sustained sucking' in VFSS. These results may have been observed because 'decreased sustained sucking' likely acted as a confounding bias, because 'desaturation' was the most common reason for referral for VFSS in the preterm infants and 'decreased sustained sucking' was frequently observed in preterm infants. Thus, since sucking-swallowing-breathing coordination is incomplete in preterm infants, preterm infants frequently experience apnea during feeding and eventually exhibit desaturation [10,13]. Cases in which VFSS was requested due to 'coughing' showed 'aspiration' in VFSS significantly more frequently; moreover, 'coughing' was the only clinical symptom that could be used to predict 'aspiration' in VFSS. However, no other clinical symptoms indicating pharyngeal-phase abnormalities, such as 'desaturation,' 'suspected aspiration pneumonia,' and 'hoarseness,' could predict pharyngeal-phase abnormalities in VFSS.

Despite the fact that there were no clear symptoms that could predict aspiration other than 'coughing,' 34 (81.0%) out of 42 infants showed 'silent aspiration' in VFSS. This result is similar to those reported in previous studies investigating the prevalence of silent aspiration by Newman et al. [3] and Arvedson et al. [14]. This indicates that many infants who are not clinically suspected of having dysphagia because they do not cough may have aspiration. Therefore, the existence of aspiration should be evaluated using VFSS in infants with a higher aspiration risk if clinical symptoms are ambiguous. Moreover, VFSS is advantageous in that it provides information regarding the diagnosis of congenital malformations such as tracheoesophageal fistula, esophageal atresia, gastroesophageal reflux, and nasopharyngeal reflux [15,16] and can effectively assess changes in swallowing functions after feeding interventions.

This study has several limitations. First, the VFSS findings of the normal control group could not be compared with those of infants with dysphagia. Second, the present study was a single-center study; therefore, the infant group might not accurately reflect the demographic characteristics and associated medical conditions of all infants with dysphagia. In particular, the high ratio of preterm infants and infants with congenital heart diseases might reflect the characteristics of the hospital in which the study was conducted.

Immediate appropriate intervention is required for infant dysphagia, because it can cause not only respiratory organ complications such as aspiration pneumonia, but also malnutrition and developmental delays [3,17,18]. Feeding interventions in infants involve position changes, flow rate adjustment, texture modification, oral stimulation, desensitization, nutritional interventions and alternative feeding [18,19]. Accurate identification of the pathophysiology of swallowing abnormalities via VFSS is helpful for determining appropriate feeding interventions [20]. However, additional studies are required to evaluate the prognosis and efficacy of interventions based on VFSS findings.

In conclusion, VFSS findings in full-term and preterm infants with dysphagia younger than 1 year were analyzed and compared. Aspiration was observed in 39.3% of infants; 81.0% of these cases were silent aspiration. When assessing infants with dysphagia, it is critical to consider that quite a few infants without coughing show aspiration, although coughing is the only indicator that could predict aspiration. In the preterm infants, 'desaturation' was a more common reason for referral for VFSS. In addition, 'decreased sustained sucking' in VFSS occurred more frequently in preterm than full-term infants. These differences will be helpful to better understand the pathophysiology of dysphagia in preterm and full-term infants.

Go to :

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Samsung Medical Center (CRS-110-32-2).

Go to :

References

1. Delaney AL, Arvedson JC. Development of swallowing and feeding: prenatal through first year of life. Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2008; 14:105–117. PMID: 18646020.

2. Bu'Lock F, Woolridge MW, Baum JD. Development of co-ordination of sucking, swallowing and breathing: ultrasound study of term and preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1990; 32:669–678. PMID: 2210082.

3. Newman LA, Keckley C, Petersen MC, Hamner A. Swallowing function and medical diagnoses in infants suspected of Dysphagia. Pediatrics. 2001; 108:E106. PMID: 11731633.

4. Arvedson J, Clark H, Lazarus C, Schooling T, Frymark T. Evidence-based systematic review: effects of oral motor interventions on feeding and swallowing in preterm infants. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2010; 19:321–340. PMID: 20622046.

5. Mercado-Deane MG, Burton EM, Harlow SA, Glover AS, Deane DA, Guill MF, et al. Swallowing dysfunction in infants less than 1 year of age. Pediatr Radiol. 2001; 31:423–428. PMID: 11436889.

6. Lee JH, Chang YS, Yoo HS, Ahn SY, Seo HJ, Choi SH, et al. Swallowing dysfunction in very low birth weight infants with oral feeding desaturation. World J Pediatr. 2011; 7:337–343. PMID: 22015726.

7. Kim TU, Park WB, Byun SH, Lee MJ, Lee SJ. Videofluoroscopic findings in infants with aspiration symptom. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2009; 33:348–352.

8. Logemann JA. Evaluation and treatment of swallowing disorders. 1998. 2nd ed. San Diego: College Hill Press;p. 168–180.

9. Hack M, Estabrook MM, Robertson SS. Development of sucking rhythm in preterm infants. Early Hum Dev. 1985; 11:133–140. PMID: 4029050.

10. McGrath JM, Braescu AV. State of the science: feeding readiness in the preterm infant. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2004; 18:353–368. PMID: 15646306.

11. Medoff-Cooper B, McGrath JM, Bilker W. Nutritive sucking and neurobehavioral development in preterm infants from 34 weeks PCA to term. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2000; 25:64–70. PMID: 10748582.

12. Medoff-Cooper B, McGrath JM, Shults J. Feeding patterns of full-term and preterm infants at forty weeks postconceptional age. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002; 23:231–236. PMID: 12177569.

13. Hanlon MB, Tripp JH, Ellis RE, Flack FC, Selley WG, Shoesmith HJ. Deglutition apnoea as indicator of maturation of suckle feeding in bottle-fed preterm infants. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1997; 39:534–542. PMID: 9295849.

14. Arvedson J, Rogers B, Buck G, Smart P, Msall M. Silent aspiration prominent in children with dysphagia. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1994; 28:173–181. PMID: 8157416.

15. Hiorns MP, Ryan MM. Current practice in paediatric videofluoroscopy. Pediatr Radiol. 2006; 36:911–919. PMID: 16552584.

16. Karkos PD, Papouliakos S, Karkos CD, Theochari EG. Current evaluation of the dysphagic patient. Hippokratia. 2009; 13:141–146. PMID: 19918301.

17. Lefton-Greif MA. Pediatric dysphagia. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2008; 19:837–851. PMID: 18940644.

18. Prasse JE, Kikano GE. An overview of pediatric dysphagia. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2009; 48:247–251. PMID: 19023104.

19. Chung SH, Beck NS, Lee M, Lee SI, Lee HJ, Choe JY, et al. Clinical manifestations of dysphagia in children. J Korean Pediatr Soc. 1999; 42:60–68.

20. Newman LA, Cleveland RH, Blickman JG, Hillman RE, Jaramillo D. Videofluoroscopic analysis of the infant swallow. Invest Radiol. 1991; 26:870–873. PMID: 1960027.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download