This article has been

cited by other articles in ScienceCentral.

Abstract

Typical venous malformations are easily diagnosed by skin color changes, focal edema or pain. Venous malformation in the skeletal muscles, however, has the potential to be missed because their involved sites are invisible and the disease is rare. In addition, the symptoms of intramuscular venous malformation overlaps with myofascial pain syndrome or muscle strain. Most venous malformation cases have reported a focal lesion involved in one or adjacent muscles. In contrast, we have experienced a case of intramuscular venous malformation that involved a large number of muscles in a lower extremity extensively.

Go to :

Keywords: Intramuscular, Lower extremity, Venous malformation

INTRODUCTION

Vascular malformations are congenital lesions due to abnormal embryonic development of vascular structures and they are subdivided into arteriovenous, capillary, venous, lymphatic and combined malformations.

1 Among them, venous malformations are the most common form and they are mostly in the skin and subcutaneous tissues.

2,

3 In this report, with a review of literature, we describe a patient with extensive intramuscular venous malformation which involved a large number of muscles in the lower extremity. Some previous cases reported a focal lesion of one or two adjacent muscles but extensive intramuscular venous malformation has rarely been reported.

Go to :

CASE REPORT

A previously healthy 36-year-old woman was presented with a year history of pain and tightness in the right proximal thigh. She reported that she felt a pain and pressure of the muscles in her right hamstring when she tried to extend the knee joint during yoga exercises. The symptoms lasted while stretching and gradually improved when she rested. On physical examination, there was full strength in all limbs and normal tone. Sensation was also intact. Reflexes were normal throughout, and there were no pathological reflexes. There was significant tenderness over a wide area of the right posterior thigh, especially medial hamstrings and the popliteal fossa. The overlying skin appeared normal without traumatic injury, erythema or warmth. The circumferences of both thighs, measured 10 centimeters (cm) above the knee, were 44.5 cm (right) and 42 cm (left), respectively. Although measurements of both legs, taken 10cm below the knee, were the same length at 34.5 cm, there was a dimpling in the right medial calf area when the patient was standing (

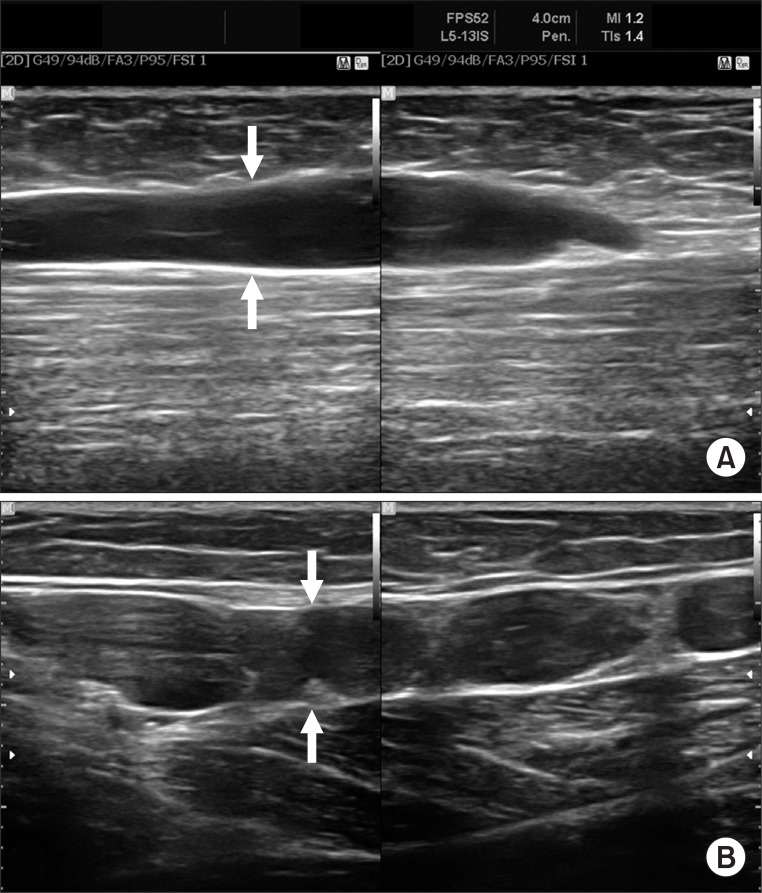

Fig. 1). The creatine kinase (CK) level was 75 U/L (normal range 51-246), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 364 IU/L (normal range 263-450) and C-reactive protein (CRP) was 0.117 mg/dl (normal range 0.02-0.3). There was a mild elevation of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) at 33 mm/hr (normal range 0-20). Ultrasonography was obtained to verify the state of the muscles and vessels on the leg and it demonstrated dilated intramuscular veins in the right medial thigh and calf, where the dimpling was seen (

Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the leg revealed multiple engorged tortuous venous structures mainly involving hamstrings, the vastus medialis, the soleus, and medial head of the gastrocnemius (

Fig. 3-A, B). Subsequent angiography and venography were performed to assess whether venous malformation was connected to the arterial system. Angiography and venography showed multiple dilated venous malformations with connection to the normal veins and no connection to the arterial system (

Fig. 3-C, D). After discussing treatment with the department of cardiothoracic surgery and radiology, we did not perform surgical resection or focal sclerotherapy, due to risk of muscle damage resulting from resection of the deeply penetrated abnormal veins. We also could not perform focal sclerotherapy due to extensive involvement of the venous malformations. We explained sufficiently about the gains and the losses of the surgery and/or sclerotherapy and met with the patient's consent of conservative management. She was encouraged to avoid excessive stretching exercises of the lower extremities and was treated with aspirin 100 mg/day to prevent deep vein thrombosis. At the current follow up, physical and laboratory examination didn't demonstrate any aggravation of the symptoms or venous malformation.

| Fig. 1Mild swelling is exhibited on the medial side of the right thigh and calf (arrow heads) and dimpling on the right medial calf area (arrow).

|

| Fig. 2Longitudinal ultrasonograms of the right medial thigh (A) and calf (B) demonstrated dilated intramuscular veins (arrows).

|

| Fig. 3Magnetic resonance images (A, B) and Venography (C, D) of the right lower extremity exhibit multiple tortous engorged venous structures mainly involving the hamstring muscles (short arrows, A, C) and soleus and gastrocnemius medial head (long arrows, B, D).

|

Go to :

DISCUSSION

Intramuscular venous malformations are rare entities. They occurred most often in the head and neck and extremities but are relatively rare in the trunk and well localized to a single muscle or adjacent muscle groups.

4 Our patient presented venous malformation confined to the right lower extremity, which is consistent with similar findings in previous reports. Because venous malformations are lesions due to abnormal embryonic development, it is assumed that localized venous malformations result from insults of the specific neurovascular bundles during development, which is the origin of some localized vessels and muscles. The muscles supplied by the nerves originated and distributed from the sciatic nerve in particular (hamstrings, soleus and gastrocnemius) were involved in our patient . Involvement of the vastus medialis was not significant. Typical subcutaneous venous malformations are grossly detectable and easily diagnosed by color changing of the skin, asymmetry of muscles, focal edema or post-exercise pain.

3,

4 According to a study by Hein at al.,

4 two-thirds of intramuscular venous malformation were also noted at birth and the remainder manifested in childhood and adolescence. However, it has the potential to be missed because they are frequently asymptomatic and their involved sites are invisible, especially during their early stages. In our patient, diagnosis of venous malformation was delayed until the age of 36 years, because the pain and pressure of the muscles were not triggered by movements in her daily life, and first appeared when she started yoga and stretching exercises. In addition, the symptoms of intramuscular venous malformation overlapped with myofascial pain syndrome or muscle strain. For this reason, a misdiagnosis was made and complications such as vessel injuries, muscle ischemia and hematoma developed after faulty trigger-point injections and so on. The superficial vascular malformations were thoroughly examined by ultrasound, with gray scale studies defining the extent and spectral and color doppler interrogation used to identify the flow characteristics.

5 Although the patient's venous malformation of the extremity was identified by musculoskeletal ultrasonography, an MRI is the most common and accurate tool of the early diagnosis of intramuscular venous malformation. The MRI demonstrated detailed distribution of the abnormal veins.

5 Doppler studies and angiography have little or no role in intramuscular venous malformations unless the diagnosis in unclear. In our case, with the suspected diagnosis of venous malformation based on presentations of the ultrasonography and MRI, an angiography and venography of the extremity were performed, which revealed extensive dilatation of the veins, compatible with venous malformation.

The initial management of venous malformations is conservative.

6 Sclerotherapy, laser therapy or surgical resection is considered after low-dose aspirin therapy, in combination with compressive garments.

6 Proper methods of treatment should be decided on after a full consideration of the degree of disabilities in daily living, injuries of adjacent tissues and cosmetic concerns. Sclerotherapy is the nonsurgical intervention for focal, well-marginated venous malformations. This approach seems to be inappropriate for larger lesions as in our case and can produce inflammatory fibrosis and a permanent scar when the chemical agent directly applied to infiltrated muscles.

7 Recurrence, focal fibrosis or contracture following surgery is also more common with diffuse venous malformations.

Our patient had minor symptoms and no disabilities in daily living for her lesion and compressive garments and low-dose aspirin were prescribed for further managements. Resection of sclerotherapy will be considered if the symptoms worsen or any complications develop later.

Go to :