Abstract

Objective

To investigate the clinical characteristics of dysphagic elderly Korean patients diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia as well as to examine the necessity of performing a videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS) in order to confirm the presence of dysphagia in such patients.

Method

The medical records of dysphagic elderly Korean subjects diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia were retrospectively reviewed for demographic and clinical characteristics as well as for VFSS findings.

Results

In total, medical records of 105 elderly patients (81 men and 24 women) were reviewed in this study. Of the 105 patients, 82.9% (n=87) were admitted via the emergency department, and 41.0% (n=43) were confined to a bed. Eighty percent (n=84) of the 105 patients were diagnosed with brain disorders, and 68.6% (n=72) involved more than one systemic disease, such as diabetes mellitus, cancers, chronic cardiopulmonary disorders, chronic renal disorders, and chronic liver disorders. Only 66.7% (n=70) of the 105 patients underwent VFSS, all of which showed abnormal findings during the oral or pharyngeal phase, or both.

Conclusion

In this study, among 105 dysphagic elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia, only 66.7% (n=70) underwent VFSS in order to confirm the presence of dysphagia. As observed in this study, the evaluation of dysphagia is essential in order to consider elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia, particularly in patients with poor functional status, brain disorders, or more than one systemic disease. A greater awareness of dysphagia in the elderly, as well as the diagnostic procedures thereof, particularly VFSS, is needed among medical professionals in Korea.

Go to :

Aspiration is defined as the inhalation of oropharyngeal or gastric contents into the larynx and lower respiratory tract. Several pulmonary syndromes may occur as a result of aspiration, depending on the amount and nature of the aspirated material, the frequency of aspiration, and the host's response to the aspirated material.1 Among such syndromes, aspiration pneumonia may arise from the inhalation of infectious oropharyngeal secretions colonized by pathogenic bacteria; this syndrome has been shown to be a significant cause of serious illness and death among hospitalized patients.1-3

The lack of specific and sensitive markers for aspiration complicates epidemiologic studies of aspiration pneumonia. Nevertheless, several studies have indicated that 5 to 15% of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) cases are associated with aspiration pneumonia.4-6 In one study comprised of patients with nursing home-acquired pneumonia and controls with CAP, the incidences of aspiration pneumonia were 18% and 5%, respectively.3 Moreover, Reza Shariatzadeh et al.7 found that 30% of the patients with continuing care facilities-acquired pneumonia involved aspiration, whereas Langmore et al.8 found that aspiration pneumonia accounted from 13% to 48% of all infections among nursing home residents.

The presence of dysphagia has been shown to be a key predisposing factor for aspiration pneumonia in elderly patients.9 In a study of elderly residents at long-term care facilities with pneumonia, swallowing difficulty and the inability to take oral medications were shown to be independent risk factors for the development of pneumonia.10 Moreover, it has been suggested that the increased incidence of pneumonia with aging may be a consequence of an impaired ability to swallow.9 Thus, evaluation of dysphagia may be essential to preventing aspiration pneumonia in elderly patients.

Unfortunately, the evaluation of dysphagia is often disregarded among medical professionals in Korea. In this study, we attempted to document the clinical characteristics of dysphagic elderly Korean patients diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia and to examine the necessity of performing videofluoroscopic swallowing study (VFSS), considered as the gold standard for examining oral and pharyngeal mechanisms of dysphagia, in order to confirm the presence thereof in such patients.11

Go to :

This study retrospectively reviewed the medical records of elderly Korean patients admitted to the Konkuk University Hospital, Seoul, South Korea, who were older than 65 years, and who underwent treatment of aspiration pneumonia during the period of August 2005 to February 2011. Aspiration pneumonia was diagnosed when patients exhibited clinically obvious aspiration. However, because episodes of aspiration are generally not observable, aspiration pneumonia was also diagnosed in patients with sudden onset of dyspnea, cyanosis, fever, diffuse rales, hypoxemia, or radiographic evidence of an infiltrate in a characteristic bronchopulmonary segment.12 Dysphagia was considered the cause of aspiration pneumonia in patients previously diagnosed with dysphagia, in those that needed multiple attempts to swallow a small bolus (fractioning), as well as in those that exhibited choking, coughing, wet voice, or nasal regurgitation after swallowing.13

Through the retrospective review of medical records, data concerning the admission route to the hospital and reasons therefore, the stay in intensive care, and the presence of a tracheostomy or parenteral tube for each patient were collected. In addition, records were reviewed for each patient's residence at pre- and post-admission. Pre-admission functional status was divided into the following three categories: independent ambulant patients, dependent ambulant patients, or patients unable to walk (bed-confined). The presence of co-morbidities including brain disorders, such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, brain tumor, Parkinson's disease, or Alzheimer's disease, and systemic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cancers, chronic cardiopulmonary disorders, chronic renal disorders, or chronic liver disorders, were also investigated.

As dysphagia is known to be a key predisposing factor for aspiration pneumonia, this study reviewed the number of times VFSS was performed in elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia. At the author's hospital, VFSS is performed by an experienced rehabilitation physician, assisted by an occupational therapist and a radiologic technician in the fluoroscopic laboratory. The results of the initial exam are then reviewed, and dysphagia is confirmed if abnormal findings during any one of the oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal phases are discovered.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software, version 17.0, and the prevalence of brain diseases among patients who underwent VFSS and those who did not undergo VFSS were compared using Pearson's chi-square test. p-values less than 0.05 were considered to be significant for all analyses.

Go to :

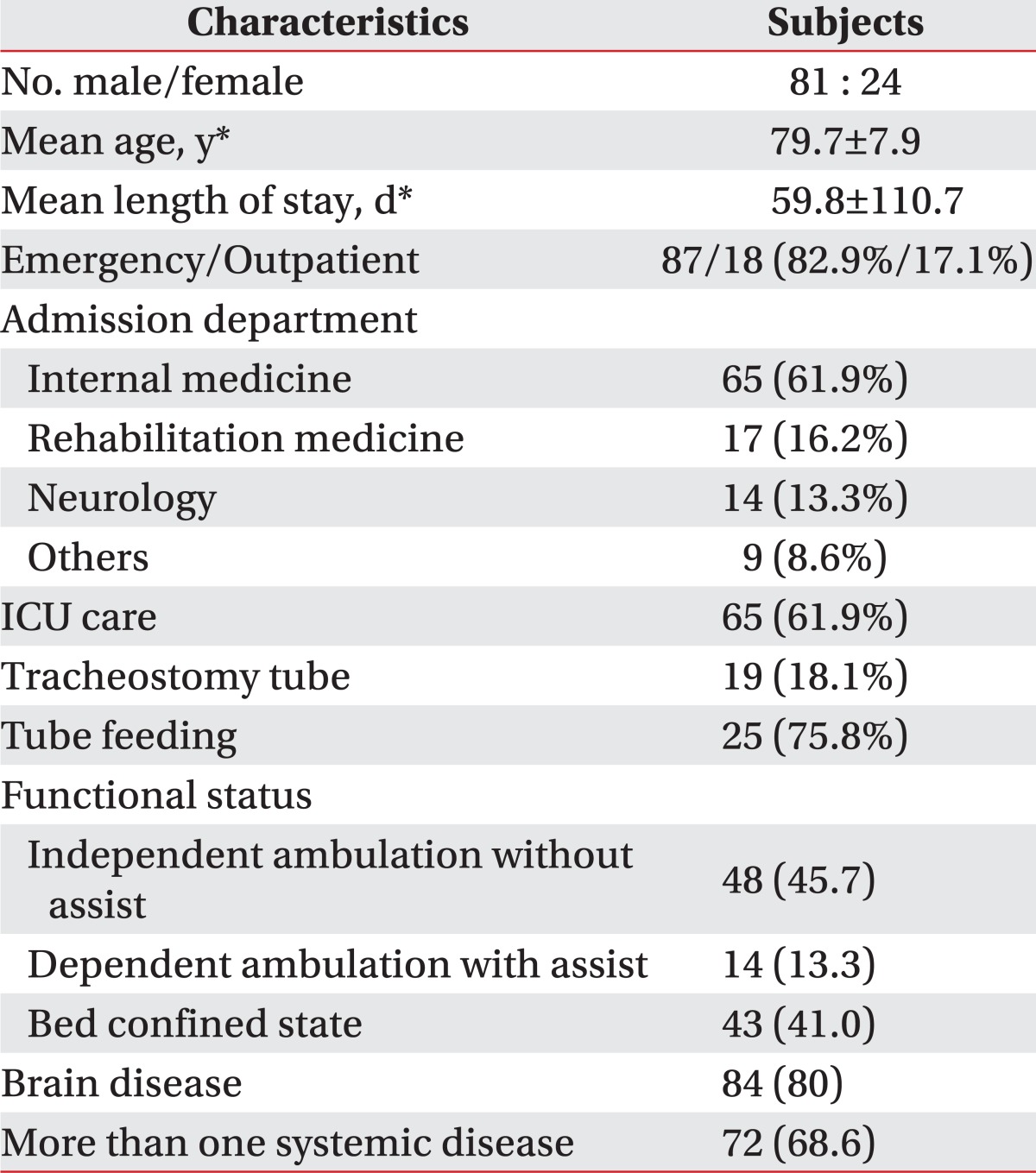

The medical records of 105 patients were reviewed in this study. The patients consisted of 81 males and 24 females with mean age of 79.7±7.9 years. The mean duration of hospital admission was 59.8±110.7 days. Of the 105 patients, 82.9% (n=87) and 17.1% (n=18) were admitted via the emergency and outpatient departments, respectively. Among the patients admitted via the emergency room, 63.6% (n=55) were admitted for pneumonia, while the others were admitted for mental change, general weakness, diarrhea, and brain disorders. Patients were more often admitted to the Department of Internal Medicine, followed by the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, and the Department of Neurology, in that order. As shown in Table 1, 61.9% (n=65) of patients received treatment in the intensive care unit, 18.1% (n=19) underwent a tracheostomy, and 56.2% (n=59) were administered a parenteral tube for feeding.

Among all 105 patients, 31.4% (n=33) had been admitted to other hospitals prior to admission to the present author's hospital, while 75.8% (n=25) resided at nursing homes. In regards to pre-admission functional status, independent ambulant patients, dependent ambulant patients, and patients confined to a bed comprised 45.7% (n=48), 13.3% (n=14), and 41.0% (n=43) of all patients, respectively. More than half of the patients demonstrated limited mobility (Table 1).

Concerning co-morbidities, 80% (n=84) of all patients were presented with brain disorders, and 68.6% (n=72) involved more than one systemic disease. Only 3.8% (n=4) involved no other co-morbidities (Table 1).

According to the patients' medical records, 14.3% (n=15) died while admitted, 47.6% (n=50) were discharged to their homes, and 38.1% (n=40) were discharged to other hospitals. Among those discharged to other hospitals, 85.0% (n=34) were discharged to a nursing home.

Only 66.7 percent (n=70) of all 105 patients underwent VFSS in order to confirm the presence of dysphagia, all of which exhibited more than one abnormal finding during the oral or pharyngeal phase, or both. However, no patients showed abnormal findings during the esophageal phase. Among the remaining 33.3% (n=35) of patients that had not undergone VFSS, only 31.4% (n=11) were discharged to their homes, 28.6% (n=10) died, and the rest were discharged to a nursing home. In the two groups of patients who underwent VFSS and those who did not undergo VFSS, 58 and 12 patients were presented with brain disorders, respectively. However, there were no significant differences between the two groups (p=0.30).

Go to :

This study is the first study in Korea to investigate the clinical characteristics of dysphagic elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia, and to examine the necessity of performing videofluoroscopic swallowing study in order to confirm the presence of dysphagia in such patients.

Dysphagia is known to be a key predisposing factor for aspiration pneumonia in elderly patients.9 As reported in previous studies, the prevalence of oropharyngeal functional dysphagia is alarmingly high in elderly patients, affecting up to 40 percent of adults aged 65 years and older as well as more than 60% of elderly institutionalized patients.9,11,13 As approximately half of all healthy adults aspirate small amounts of oropharyngeal secretions during their sleep,14,15 presumably, the low burden of virulent bacteria in normal pharyngeal secretions, together with forceful coughing, active ciliary transport, and normal humoral and cellular immune mechanisms, allows for the clearance of infectious materials without sequelae. However, the elderly exhibit increased oropharyngeal colonization of pathogens, such as Staphylococcus aureus and aerobic Gram-negative bacilli, reduced lung function, and a progressive decline in immune system integrity, leading to an increased incidence of aspiration pneumonia and mortality.1,9,16 Therefore, greater consideration and evaluation of dysphagia is warranted in elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia.

In a previous study by Cabre et al.,17 the Barthel Index score, a measure of daily function, upon admission was significantly lower in dysphagic elderly patients with pneumonia than in elderly patients with pneumonia without oropharyngeal dysphagia. In our study, 41% of all patients were bed-confined and unable to ambulate at all. In patients with limited mobility, aspiration can easily occur as the result of an unstable position while eating, which restricts the ability of the pharynx to protect the airway. Fortunately, aspiration can be reduced when an appropriate position is assumed.18 Therefore, evaluation of changes in the swallowing function and assuming an appropriate position while eating should be stressed in elderly patients with limited mobility in order to prevent aspiration pneumonia.

Dysphagia may result from structure-related or functional causes. However, dysphagia in the elderly is more frequently the result of a functional disorder of deglutition caused by aging, brain disorders, or associated with systemic diseases, affecting the oropharyngeal swallow response.11 Functional dysphagia was previously shown to afflict more than 30% of patients who had experienced a cerebrovascular accident.11 In patients with acute stroke, the incidence of dysphagia was shown to range from 40 to 70%.9 In particular, elderly patients are at risk of silent infarction. Nakagawa et al.19 demonstrated that elderly patients with silent cerebral infarction involve a fivefold higher risk of developing pneumonia than elderly patients with normal head CT scans. Moreover, functional dysphagia was shown to affect 52 to 82% of patients with Parkinson's disease, and 84% of patients with Alzheimer's disease.11

Along with reductions in mucociliary transport, reduced pulmonary elasticity, and decreased respiratory muscle strength, the progressive decline in the integrity of the immune system has also been described as part of the aging process. Furthermore, as elderly patients are known to demonstrate decreased activation of the immune system responses following antigen challenge due to age-related changes in the peripheral T-cell pools, aging is considered a risk factor for aspiration pneumonia.20-23 Accordingly, the underlying systemic disease has also been shown to be associated with functional dysphagia as well as a higher incidence of pneumonia in the elderly.8,11 In our study, among all 105 elderly patients, the prevalence of brain disorders, such as stroke, traumatic brain injury, brain tumor, Parkinson's disease, or Alzheimer's disease, was 80% for all patients; the prevalence of more than one systemic disease, such as diabetes mellitus, cancers, chronic cardiopulmonary disorders, chronic renal disorders, or chronic liver disorders, was 68.6%. Only 3.8 percent of all patients involved no co-morbidities. Therefore, medical professionals should consider functional dysphagia as a cause of aspiration pneumonia in elderly patients with brain disorders or systemic disease.

In spite of its enormous impact on the functional capacity, health, and quality of life of the patients who suffer from dysphagia, it is underestimated and underdiagnosed as a cause of major respiratory complications in elderly patients in Korea. In our study, all patients who underwent VFSS showed more than one abnormal finding in the oral or pharyngeal phase, or both. However, 33.3 percent of all 105 patients did not undergo VFSS to investigate the presence of dysphagia. Generally, due to the high prevalence of dysphagia among patients with brain disorders, the evaluation of dysphagia is often undertaken. Considering this, all patients were divided into two groups according to whether or not VFSS was performed to confirm the presence of dysphagia in this study. However, the two groups showed no significant differences in regards to the presence of brain disorders (p=0.30), suggesting that the awareness of the necessity of performing dysphagia evaluation among medical professionals in Korea is poor. As previously mentioned, dysphagia is the major pathophysiologic mechanism leading to aspiration pneumonia in the elderly; therefore, a greater awareness of dysphagia in the elderly, as well as the diagnostic procedures thereof, is essential among medical professionals in Korea.9,24

VFSS is the most commonly utilized instrumental assessment tool in the clinical setting to evaluate the safety and efficacy of deglutition, and is considered the gold standard for visualizing the anatomic structures and swallow physiology of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, and upper esophagus during deglutition.9,11 VFSS is a dynamic radiological technique by which a sequence of both lateral and postero-anterior images may be obtained following the oral administration of several volumes and different viscosities of a water-soluble contrast. In VFSS, swallowing alterations during the oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal phases can be characterized in terms of videofluoroscopic signs, and quantitative data on oropharyngeal biomechanics can be obtained to identify silent aspiration, which is clinically undiagnosable. In addition, not only can treatment selection, according to the severity of impairment in the efficacy or safety of swallowing for individual patients be more accurately considered, but also, the effectiveness of treatments can be evaluated with VFSS.13 In a previous study, Terre and Mearin25 demonstrated that the indication for the chin-down maneuver to prevent aspiration in patients with dysphagia, secondary to acquired brain injury, cannot be generalized, as only half of their patients avoided aspiration while performing this maneuver, which was confirmed by VFSS. Terre and Mearin25 concluded that the appropriate indication for the chin-down posture should be based upon VFSS. Furthermore, VFSS objectively demonstrates inabilities of the oral route and the need to perform a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.13,26 Taken together, VFSS is the most effective method for evaluating swallowing and treatment selection in elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia as the result of dysphagia, which is more frequently a functional disorder of deglutition. Accordingly, medical professionals should consider performing VFSS in elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia, particularly in those with limited mobility or co-morbidities, such as brain disorders or systemic diseases.

This study had several limitations, including the absence of a control group and the retrospective nature of the study. This study also did not include dysphagia treatment in the scope of the study, but rather focused solely on dysphagia evaluation. Further study is needed to investigate the efficacy of dysphagia treatment based on VFSS. Lastly, the functional status was not investigated in detail. Further studies assessing the functional status in greater detail, in addition to mobility, by a validated tool, such as the Barthel Index, is needed.

Go to :

In spite of its enormous impact on the functional capacity, health, and quality of life of the patients who suffer from it, dysphagia is underestimated and underdiagnosed as a cause of major respiratory complications in elderly patients, among medical professionals in Korea. Medical professionals in Korea should develop greater awareness of the clinical characteristics of dysphagic elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia, as well as VFSS in order to evaluate dysphagia. Evaluation of dysphagia must be considered in elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia, particularly in those with limited mobility or co-morbidities, such as brain disorders or systemic diseases.

Go to :

References

1. Marik PE. Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2001; 344:665–671. PMID: 11228282.

2. Beck-Sague C, Villarino E, Giuliano D, Welbel S, Latts L, Manangan LM, Sinkowitz RL, Jarvis WR. Infectious diseases and death among nursing home residents: results of surveillance in 13 nursing homes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1994; 15:494–496. PMID: 7963443.

3. Marrie TJ, Durant H, Kwan C. Nursing home-acquired pneumonia. A case-control study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986; 34:697–702. PMID: 3489749.

4. Torres A, Serra-Batlles J, Ferrer A, Jimenez P, Celis R, Cobo E, Rodriguez-Roisin R. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Epidemiology and prognostic factors. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991; 144:312–331. PMID: 1859053.

5. Moine P, Vercken JB, Chevret S, Chastang C, Gajdos P. French Study Group for Community-Acquired Pneumonia in the intensive Care Unit. Severe community-acquired pneumonia. Etiology, epidemiology, and prognosis factors. Chest. 1994; 105:1487–1495. PMID: 8181342.

6. Marrie TJ, Durant H, Yates L. Community-acquired pneumonia requiring hospitalization: 5-year prospective study. Rev Infect Dis. 1989; 11:586–599. PMID: 2772465.

7. Reza Shariatzadeh M, Huang JQ, Marrie TJ. Differences in the features of aspiration pneumonia according to site of acquisition: community or continuing care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006; 54:296–302. PMID: 16460382.

8. Langmore SE, Terpenning MS, Schork A, Chen Y, Murray JT, Lopatin D, Loesche WJ. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia: how important is dysphagia? Dysphagia. 1998; 13:69–81. PMID: 9513300.

9. Marik PE, Kaplan D. Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Chest. 2003; 124:328–336. PMID: 12853541.

10. Loeb M, McGeer A, McArthur M, Walter S, Simor AE. Risk factors for pneumonia and other lower respiratory tract infections in elderly residents of long-term care facilities. Arch Intern Med. 1999; 159:2058–2064. PMID: 10510992.

11. Rofes L, Arreola V, Almirall J, Cabre M, Campins L, Garcia-Peris P, Speyer R, Clave P. Diagnosis and management of oropharyngeal dysphagia and its nutritional and respiratory complications in the elderly. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011; 2011:pii: 818979.

12. Seo WH, Oh JH, Nam YH, Sung IY. Clinical study of aspiration pneumonia in stroke patients. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 1994; 18:52–58.

13. Clave P, Terre R, de Kraa M, Serra M. Approaching oropharyngeal dysphagia. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2004; 96:119–131. PMID: 15255021.

14. Gleeson K, Eggli DF, Maxwell SL. Quantitative aspiration during sleep in normal subjects. Chest. 1997; 111:1266–1272. PMID: 9149581.

15. Huxley EJ, Viroslav J, Gray WR, Pierce AK. Pharyngeal aspiration in normal adults and patients with depressed consciousness. Am J Med. 1978; 64:564–568. PMID: 645722.

16. Palmer LB, Albulak K, Fields S, Filkin AM, Simon S, Smaldone GC. Oral clearance and pathogenic oropharyngeal colonization in the elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001; 164:464–468. PMID: 11500351.

17. Cabre M, Serra-Prat M, Palomera E, Almirall J, Pallares R, Clave P. Prevalence and prognostic implications of dysphagia in elderly patients with pneumonia. Age Ageing. 2010; 39:39–45. PMID: 19561160.

18. Chung SG, Lee SJ, Hyun JK, Park SG. The effects of posture and bolus viscosity on swallowing in patients with dysphagia. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 1997; 21:20–29.

19. Nakagawa T, Sekizawa K, Nakajoh K, Tanji H, Arai H, Sasaki H. Silent cerebral infarction: a potential risk for pneumonia in the elderly. J Intern Med. 2000; 247:255–259. PMID: 10692089.

20. Caruso C, Candore G, Cigna D, DiLorenzo G, Sireci G, Dieli F, Salerno A. Cytokine production pathway in the elderly. Immunol Res. 1996; 15:84–90. PMID: 8739567.

21. Miller RA. The cell biology of aging: immunological models. J Gerontol. 1989; 44:B4–B8. PMID: 2642937.

22. Saltzman RL, Peterson PK. Immunodeficiency of the elderly. Rev Infect Dis. 1987; 9:1127–1139. PMID: 3321363.

23. Thoman ML, Weigle WO. The cellular and subcellular bases of immunosenescence. Adv Immunol. 1989; 46:221–261. PMID: 2528897.

24. Ekberg O, Hamdy S, Woisard V, Wuttge-Hannig A, Ortega P. Social and psychological burden of dysphagia: its impact on diagnosis and treatment. Dysphagia. 2002; 17:139–146. PMID: 11956839.

25. Terre R, Mearin F. Effectiveness of chin-down posture to prevent tracheal aspiration in dysphagia secondary to acquired brain injury. A videofluoroscopy study. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012; 24:414–441. PMID: 22309385.

26. Mazzini L, Corra T, Zaccala M, Mora G, Del Piano M, Galante M. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy and enteral nutrition in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurol. 1995; 242:695–698. PMID: 8568533.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download