Abstract

Massage is generally accepted as a safe and a widely used modality for various conditions, such as pain, lymphedema, and facial palsy. However, several complications, some with devastating results, have been reported. We introduce a case of a 43-year-old man who suffered from tetraplegia after a neck massage. Imaging studies revealed compressive myelopathy at the C6 level, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), and a herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) at the C5-6 level. After 3 years of rehabilitation, his motor power improved, and he is able to walk and drive with adaptation. OPLL is a well-known predisposing factor for myelopathy in minor trauma, and it increases the risk of HNP, when it is associated with the degenerative disc. Our case emphasizes the need for additional caution in applying manipulation, including massage, in patients with OPLL; patients who are relatively young (i.e., in the fifth decade of life) are not immune to minor trauma.

Spinal cord injury may cause diverse problems, such as motor impairment, sensory impairment, respiratory dysfunction, deep vein thrombosis, chronic pain and spasticity.1 Most cases of the spinal cord injury occur because of the major trauma. However, if there are risk factors, they might also occur because of the minor trauma. The ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) may cause spinal stenosis. In addition, it has been known as a factor that triggers the occurrence of spinal cord injury, even following the minor injury, such as a whiplash injury or a low-height fall.2

The massage therapy is performed for various purposes, such as alleviation of the musculoskeletal and neurogenic pain, improvement of blood circulation and that of lymphatic circulation. Although there are insufficient amount of objective evidences for the treatment effect, it has long been performed in different countries with various cultural backgrounds.3,4 Several complications of massage therapy that have been reported are vascular injury, stroke, ulcer, pulmonary artery embolism, and etc. In regard to the safety of massage, Ernst reported 20 cases of complications of the massage therapy in 2003 and concluded that massage therapy is not always safe.5

We experienced a case of spinal cord injury incurred by a neck massage, which has not been reported yet. Here, we report our case with a review of literatures.

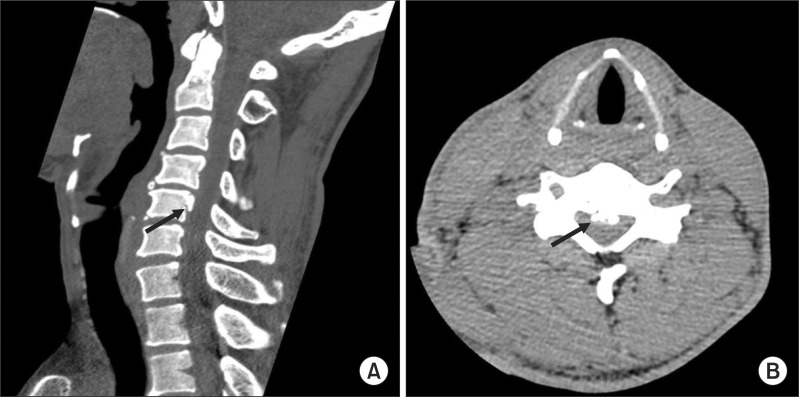

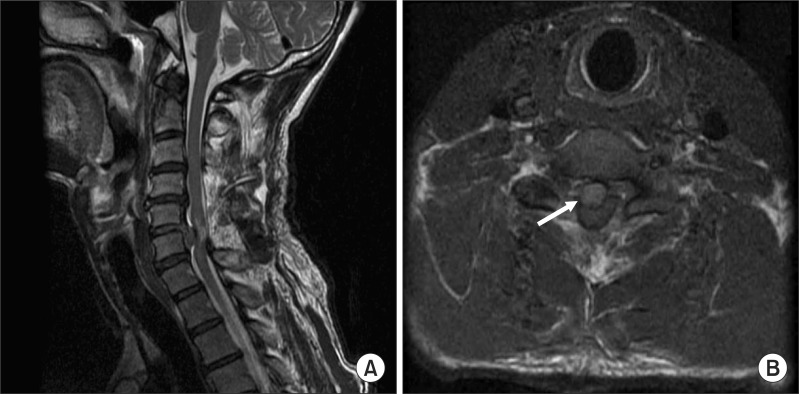

A 43-year-old man had no notable findings on a past history, and he worked in a moving company. Due to the pain in the neck and shoulder, the patient received a cervical massage from a massage therapist with a private certificate at a massage center in Kyounggi province, in March of 2008. The massage was performed in such a manner that the massage therapist pressed the patient's back with the palm and then pushed it in an upward direction from the thoracic to the cervical in a prone position. During the massage, the patient had a sensation of paralysis in the right upper and lower extremities. Because the weakness was not severely notable, however, the patient returned home with no other specific treatments. On the evening of that day, the patient felt a weakness in all the extremities, and then visited an emergency care center of another hospital. An OPLL was revealed in the fifth cervical spine on a cervical computed tomography, which was performed at an emergency care center (Fig. 1-A, B). On a cervical magnetic resonance imaging, there was an acute herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP) between the C5 and C6. Further, T2-weighted images showed a high signal intensity, which is indicative of myeolopathy around the sixth cervical spine (Fig. 2-A, B). The patient had undergone a sixth cervical corpectomy, the anterior cervical fusion and the device fixation for the fifth to seventh cervical spine, the posterior cervical fusion and the device fixation for the third to seventh cervical spine and the posterior laminectomy for the fourth to the sixth cervical spine (Fig. 3-A, B).

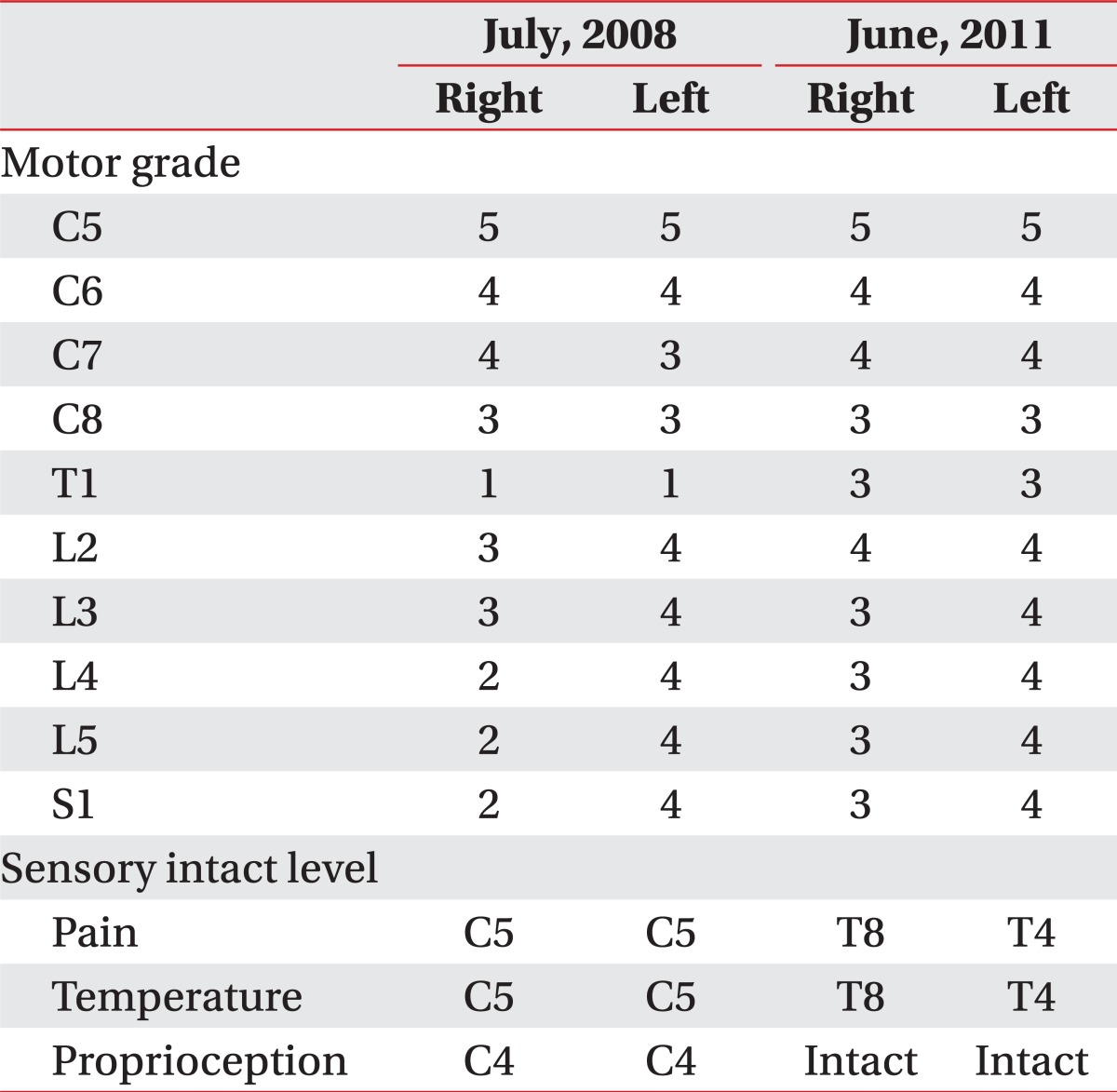

Four months following the onset of the trauma, the patient was referred to the department of rehabilitation medicine in our hospital to receive a comprehensive rehabilitative treatment. The results of a manual muscle test and sensation test are shown in Table 1. Based on a neurologic level of injury of C4 and an ASIA Impairment Scale of D according to the criteria of the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA), the patient was diagnosed with incomplete spinal cord injury (Table 1). In addition, an electrophysiologic test was also performed at four months following the onset of the trauma. The sensory and motor nerve conduction studies were normal and no significant difference was noted between both sides. On a needle electromyography, abnormal spontaneous activities were found in the right C5-C7, the left C4-C5, C6-C7 paraspinal muscles, the both triceps brachii, the flexor carpi radialis, the extensor digitorum communis and the first dorsal interosseous muscles. Besides, the recruitment patterns of the motor unit action potentials were decreased in both triceps brachii, the flexor carpi radialis and the extensor digitorum communis muscles. These led to the diagnosis of bilateral lower cervical radiculopathy. The muscle stretch reflexes were increased in the upper and lower extremities on both sides. Hoffmann's sign and ankle clonus were observed on both sides. The patient was able to walk using a walker at indoors, and he needed a minimal assist to perform activities of daily living, such as grooming, feeding, dressing, transfer from a bed to a wheelchair and a gait. But, the patient needed a moderate assist to perform such activities as toileting and bathing. Therefore, the Korea spinal cord independence measure (KSCIM) was 67/100. Following a 3-week of comprehensive rehabilitative therapy, the patient was discharged in such a condition that the patient walked independently indoors with a right ankle foot orthosis.

The patient received a physical and occupational therapy, and was monitored of the clinical course at an outpatient clinic of the rehabilitation medicine in our institution. Three years after the trauma, a manual muscle test showed that the muscle strength was increased in the left elbow extensor, both finger abductor, the right hip flexor, the right ankle dorsiflexor, the right ankle plantar flexor, and the right great toe extensor muscles. The pain and temperature sensation were normal up to the level of T8/T4 (right/left), and the proprioception was improved to the normal range at all the spinal levels. This led to changes in a neurologic level of an injury to C6 (Table 1). Furthermore, the patient was able to perform most of the activities of daily living, including outdoor walking and driving, without an orthosis. Therefore, the score of KSCIM was 97/100. But the patient needed to hold a balustrade, while going up and down the stairs, used a fork because of the difficulty in using a chopstick when having a meal, and usually wore clothes without buttons because of the difficulty in manipulating the buttons. That is, the patient had a restriction in going up and down the stairs and performing a fine motor coordination.

The massage therapy has such a long history that it was first recorded in the Chinese history in the second century BC, and it is referred to as a manual manipulation of the soft tissue for the purposes of treating the musculoskeletal pain, correcting the body alignment, and improving the blood circulation, improving the lymphatic circulation and correcting the body alignment.3,4 Despite such a long history and a wide spread use of the massage therapy, however, there are almost no systematic studies regarding its effectiveness. According to Tsao, the massage therapy was effective for the treatment of non-specific low back pain when it was combined with exercise and education in patients with chronic non-malignant pain. This author noted, however, that the effects of massage therapy was relatively lower than that of the manipulation or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation; there was a moderate level of evidence for the treatment effect on the shoulder pain and headache; and there was a modest level of evidence for the treatment effect on the pain in the neck, carpal tunnel syndrome, fibromyalgia and mixed chronic pain conditions. The massage therapy has not been considered commonly as the primary therapy, but as the supplemental one to the physical or pharmacological treatments. Nevertheless, it has been increasingly demanded by patients.4 This might be not only because patients have a lesser extent of fear against the side effects of the massage treatment, but also because of the accessibility, as the number of facilities or institutions for the massage therapy has been increasing.

There are almost no guidelines for the safety and contraindications of the massage therapy. But the traditional contraindications include infections, malignant tumor, dermatologic diseases, burn and thrombophlebitis.6 Ernst reviewed literatures concerning the complications of massage therapy that had occurred during a period ranging from 1995 to 2001, where a total of 20 cases were described. The complications with the highest incidence are related with vascular injuries, there were embolism in the lung, kidney and retina, pseudoaneurysm of the popliteal artery, the stenosis of the internal carotid artery and giant hematoma. Moreover, there were also such cases as the death from asphyxia, the rupture of the uterus occurring during the abdominal massage of pregnant women and the intracranial hemorrhage of the fetus.5

Spinal cord injury may cause various problems, such as motor and sensory impairment, respiratory dysfunction, deep vein thrombosis, pain and spasticity. These eventually lead to the shortened lifespan and the decreased quality of life.1 According to the 2011's statistics of the National spinal cord injury statistical center, the causes of the spinal cord injury in the US include the traffic accident (33.8%), being the most prevalent, a fall (20.9%), a firearm accident (15.8%), diving (6.3%), bike accident (5.9%), accident due to falling object (2.9%) and the medical and surgical complications (2.5%). In most cases, the trauma is one of the major causes of the spinal cord injury. In particular, a great majority of injuries originated from major traumas, large high speed impacts. Because, the spinal stenosis could occur in the presence of OPLL, irreversible spinal cord injury could also occur by minor traumas, such as a fall, a whipplash injury due to a mild traffic accident and a collision with a flying object having no direct impact on the neck, or an object fallen from a height of less than 2 m. Katoh et al. conducted a follow-up study during the mean period of 5.5 years in 118 patients with OPLL. According to these authors, 27 patients had minor traumas. Among the 27 patients, 19 patients had no past history of myelitis, and of these, 13 patients (68.4%) were newly diagnosed with myelitis. Of the eight patients who already had a myelitis, seven (87.5%) had an aggravation of pre-existing lesion.2

It is known that there is a relationship between the spinal cord injury and spinal stenosis in patients with OPLL. But, scarce cases have been reported in association with non-traumatic acute HNP. Cases of spinal cord injury occurred because of the non-traumatic acute HNP in a 68-year-old man7 and spinal cord injury occurred by an acute HNP, following a spinal manipulation therapy in a 61-year-old woman8 were reported in patients with OPLL in 2006 and 2010, respectively. However, there is no case of spinal cord injury that have been reported in association with the massage therapy.

In the present case, the spinal cord injury occurred because of the massage which was performed by the human hand, a physical impact that is generally considered to have a lesser extent of the detrimental effect. Presumably, the current case might be originated from OPLL and traumatic acute HNP that had not been diagnosed previously, and both of which are risk factors for the development of spinal stenosis.

According to the studies that had been conducted during a period ranging from 2002 to 2005 in Korean adults aged 16 years or older, the prevalence of OPLL was 0.6%. This figure is relatively smaller, as compared with those reported in Japan or other western countries.9 In regard to the age of patients, the prevalence of OPLL has been increased as the age of patients was increased. Further, the prevalence was 1.36% in Korean patients in their sixth decade. According to this report, at the mean prevalence of 1/200 in Korea (approximately 1/100 in patients in their sixth decade), patients might have OPLL during a massage therapy irrespective of whether it is diagnosed or undiagnosed. Besides, considering that the massage therapy is commonly performed for various types of patient groups and is done more prevalently at private institutions in the non-medical environment, the risk of spinal cord injury might be more than the usual expectation.

In our case, compressive myelopathy occurred after massage therapy induced tetraplegia and neuropathic pain. This restricted some parts of the activities of daily living and those for work and social lives. In addition, eventually, there were fatal effects on the quality of life of the patient. Therefore, it is necessary to make an effort to identify the risk factors that make the patients vulnerable even to a mild trauma that are commonly encountered in an outpatient setting, and these include OPLL. In patients with OPLL, it would be imperative that they should be alert to a mild trauma, though it can commonly be overlooked, because it could be a risk factor for developing spinal cord injury. In addition, the massage therapy has been performed at various private institutions because it has been considered as a relatively safe method. However, it should be widely informed that the massage therapy deserves special attention, as this may induce an acute HNP and spinal cord injury.

References

1. Branco F, Cardenas DD, Svircev JN. Spinal cord injury: a comprehensive review. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007; 18:651–679. PMID: 17967359.

2. Katoh S, Ikata T, Hirai N, Okada Y, Nakauchi K. Influence of minor trauma to the neck on the neurological outcome in patients with ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) of the cervical spine. Paraplegia. 1995; 33:330–333. PMID: 7644259.

3. Vickers A, Zollman C. ABC of complementary medicine. Massage therapies. BMJ. 1999; 319:1254–1257. PMID: 10550095.

4. Tsao JC. Effectiveness of massage therapy for chronic, non-malignant pain: a review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007; 4:165–179. PMID: 17549233.

6. Knapp ME. Kottke FJ, Lehmann JF, editors. Massage. Krusen's handbook of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 1990. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders;p. 435.

7. Seo JG, Kim JY, Choi HJ. Acute myelopathy due to ruptured HNP in cervical OPLL patient. J Korean Soc Spine Surg. 2006; 13:323–326.

8. Hsieh JH, Wu CT, Lee ST. Cervical intradural disc herniation after spinal manipulation therapy in a patient with ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament: a case report and review of the literature. Spine. 2010; 35:E149–E151. PMID: 20190620.

9. Kim TJ, Bae KW, Uhm WS, Kim TH, Joo KB, Jun JB. Prevalence of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament of the cervical spine. Joint Bone Spine. 2008; 75:471–474. PMID: 18448378.

Fig. 1

Computed tomography images of cervical spine showed ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament at C5 level (black arrows). (A) Sagittal view. (B) Axial view.

Fig. 2

Magnetic resonance image of cervical spine was undergone. (A) T2-weighted sagittal view showed increased signal intensity at C5 spinal cord level. (B) T1-weighted axial image showed herniated nucleus pulposus at C5-6 level (white arrow).

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download