Abstract

Vascular malformations in extremities are difficult to detect in cases of minor trauma. The authors report a case of an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) incidentally found by ultrasonography in a contusion. After a slip down, a 52-year-old man who had undergone total arthroplasty in both hips 10 years earlier complained of an ovoid right hip swelling that had gradually increased in size. Suspecting a simple cyst or hematoma, the swelling was examined by ultrasonography, which revealed a subcutaneous hematoma with arterial flow connected to muscle. Arteriography revealed an AVM around the right hip joint. Due to the presence of multiple arteriovenous shunts, a conservative treatment course was adopted and after 3 weeks of treatment the swelling almost completely resolved. It appears that the small AVM may have existed congenitally before hip surgery and the contusion over the AVM had led to hematoma rather than an arteriovenous fistula. The authors emphasize the usefulness of ultrasonography for the diagnosis of posttraumatic swelling.

Contusions cause damage to soft tissues, such as muscles and subcutaneous tissues, in the proximity of ruptured capillary vessels or veins, and may lead to the development of masses, such as seromas or hematomas, that may require aspiration therapy. However, a thorough evaluation of the distribution of vascular structures supplying masses should be considered when the risk of hemorrhage is considered, and when masses have an abundant blood supply. Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are defined as congenital abnormal direct connections between arteries and veins in the absence of capillaries. Furthermore, AVMs can be asymptomatic, and thus, occasionally found incidentally.1 In this study, we report a case of hematoma after contusion in a patient with an asymptomatic AVM that was diagnosed by ultrasonography and angiography.

A 52-year-old male patient visited our department with a palpable mass in the right lateral thigh following contusion after a slip-down injury 10 days earlier. The mass subsequently progressively enlarged but was otherwise asymptomatic. A medical history revealed bilateral total hip replacement arthroplasty 10 years earlier due to avascular necrosis of both hip joints. The patient had not suffered from any postoperative complications. Furthermore, there was no medical history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or hematologic disease. However, the patient was on mood stabilizers, including diazepam, imipramine, perphenazine, and nortriptyline, to treat depression. A laboratory examination of blood samples revealed values were within normal limits [prothrombin time (PT) of 0.97 (INR; International Normalization Ratio, normal range: 0.8-1.2), activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) of 33.2 seconds (normal range: 25-40 seconds), and a platelet count of 272,000 (/ul) (normal range: 140,000-400,000/ul)]. In addition, complete blood count (CBC) and liver function test findings were also normal.

The 5.5×7×2 cm sized, ovoid mass was located just beneath the right greater trochanter. It was soft to touch and there were no signs of redness or heating. Furthermore, a physical examination revealed no tenderness, and hip joint ranges of motion were intact. A simple radiographic examination provided no evidence of fracture. High frequency (7-14 MHz) ultrasonography Xario® (Toshiba Co., Tokyo, Japan) was performed using a linear probe under suspicion of seroma or hematoma and for the planning of aspiration if required. Ultrasonography revealed a heterogenous low echogenic mass with acoustic enhancement at the subcutaneous layer above the fascia of the right vastus lateralis muscle, suggestive of a lesion with cystic contents (Fig. 1-A). However, pulsatile arterial stalk flow was observed between the inner cyst and the vastus lateralis in power and simple Doppler modes (Fig. 1-B, C). Angiography was performed on both femoral arteries to identify any vascular malformation, and blood supply into the mass was observed from the right internal iliac artery and deep femoral artery. In addition, enhanced nidus, early enhancement of the draining vein, and arteriovenous shunting were observed within the mass; consistent with an arteriovenous malformation (AVM) (Fig. 2). It was then concluded that the mass had formed as a result of contusion in the femoral region containing a congenital arteriovenous malformation of the right internal iliac artery and deep femoral artery.

Surgical resection or interventional embolization was considered difficult due to abundant vascular shunting shown by angiography, and we decided on close observation and conservative management. A follow-up examination performed 3 weeks later showed a reduction in mass size, which was considered to be probably due to natural absorption. No further follow-up evaluation was conducted.

This article describes a case of a previously unidentified congenital arteriovenous malformation diagnosed by Doppler ultrasonography and angiography following mass formation due to hemorrhage after traumatic contusion. Ultrasonographic findings resulted in consideration of a Morel-Lavallee lesion in the differential diagnosis, because its echogenicity is similar to that of hematoma due to post-traumatic seroma between the fascia and the deep layer of the subcutaneous tissue caused by shear strain along the trochanteric region followed by hemorrhage of the rich vascular plexus that pierces the fasciae latae.2 However, due to evidence of arterial blood flow, suggesting a vascular abnormality, angiography was performed.

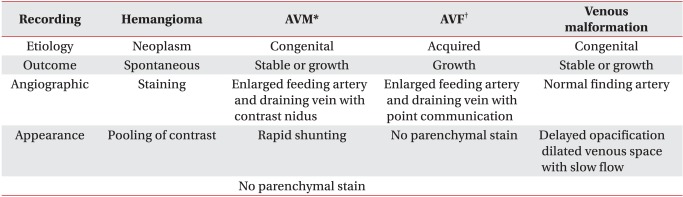

Based on the assumption that the femoral vascular abnormality began after total hip replacement arthroplasty, the possibility of an acquired arteriovenous fistula (AVF) was considered a priority. Vascular malformations include AVM, AVF, and hematoma, which have quite different characteristics (Table 1).3 AVF usually occurs in patients with a penetrating injury, such as a stab or gunshot wound, or after surgery. An abnormal connection between an artery and a vein on angiograms is characteristic.4 They can also be caused by traction, pressure, and stretching by surgical instruments or by direct injury during total hip replacement arthroplasty,5 in which its incidence has been reported to be 3%.6 In fact, AVF accounts for 13% of the arterial injuries encountered after hip and knee surgeries.7

The diagnosis of AVM was made for the following reasons. First, angiographic findings indicated an AVM. Angiograms showed numerous nidi, that is abnormal vascular connections between arteries and veins in the mass, dilatation of feeding arteries, delayed filling of distal arteries, and early filling of distal veins on contrast enhancement, which are entirely consistent with an AVM. Furthermore, these findings differ from AVF, in which only one connection point resides between the affected artery and vein.8

Second, previous reports have described AVM formation after total hip replacement arthroplasty. Winemaker et al.9 reported one case of AVM diagnosed by angio graphy in a patient who underwent total hip replacement arthroplasty and later revision due to simple radiographic findings suggestive of osteolysis. During revision, the patient suffered excessive bleeding, and was diagnosed with AVM, and treated with selective arterial embolization. Authors suggested that there may have been a preexisting AVM before joint arthroplasty. The symptoms of AVM range from asymptomatic to potentially lethal conditions, such as hemorrhage and heart failure. Under circumstances that trigger hormonal changes, such as trauma, pregnancy, secondary sexual growth, or drug intake, hemodynamic changes may increase the size of any AVM and cause new symptoms or aggravate existing symptoms.8 In our case, a congenital asymptomatic AVM existed prior to total hip replacement arthroplasty, and we presume that the hematoma developed due to traumatic contusion. However, surgery was performed ten years earlier, which made it difficult to confirm the existence of excessive hemorrhage or of an AVM based on a literature review of medical records.

In cases of asymptomatic arteriovenous malformation, conservative management should be carried out as a priority. On the other hand, surgical resection has limited indications and is associated with the possibilities of recurrence and deterioration. However, recent reports suggest that excellent results can be obtained by interventional ethanol embolization.10

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Healthcare Technology R&D Project. Ministry for Health, Welfare & Family Affairs, Republic of Korea (A090084).

References

1. Das S, Othman F, Suhaimi FH. Congenital arteriovenous communication in the arm: a cadaveric study. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2008; 49:421–423. PMID: 18758652.

2. Martinoli C, Bianchi S. Bianchi S, Martinoli C, editors. Hip. Ultrasound of the musculoskeletal system. 2007. 1st ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag;p. 594.

3. Kaufman JA, Lee MJ. Vascular & interventional radiology. 2004. 1st ed. Philadelphia: Mosby;p. 1–30.

4. Schultz RC, Hermosillo CX. Congenital arteriovenous malformation of the face and scalp. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980; 65:496–501. PMID: 7360819.

5. Lewallen DG. Neurovascular injury associated with hip arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect. 1998; 47:275–283. PMID: 9571429.

6. Shoenfeld NA, Stuchin SA, Pearl R, Haveson S. The management of vascular injuries associated with total hip arthroplasty. J Vasc Surg. 1990; 11:549–555. PMID: 2182915.

7. Kickuth R, Anderson S, Kocovic L, Ludwig K, Siebenrock K, Triller J. Endovascular treatment of arterial injury as an uncommon complication after orthopedic surgery. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006; 17:791–799. PMID: 16687744.

8. Konez O. Vascular anomalies (Birthmarks) of the foot and ankle. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2004; 94:477–482. PMID: 15377724.

9. Winemaker MJ, Boucher MA, de V deBeer J, Colterjohn N, Petruccelli D. Arteriovenous malforma tion mimicking femoral osteolysis after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2001; 16:394–399. PMID: 11307141.

10. Do YS, Park KB, Cho SK. How do we treat arteriovenous malformations (tips and tricks)? Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007; 10:291–298. PMID: 18572144.

Fig. 1

High frequency ultrasonography of the lateral thigh. The hypoechoic ovoid mass filled with heterogenous hypoechoic material showed posterior acoustic enhancement (interpreted as a cystic mass containing debris and hematoma) in subcutaneous tissue above the fascia of the vastus lateralis. Power Doppler mode (B) and color Doppler mode (C) showed pulsatile arterial blood flow through a stalk between the cystic lesion and the vastus lateralis.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download