Abstract

Objective

To examine the effects of age, gender and bolus consistency in normal populations using the temporal measurement of Pharyngeal Transit Duration (PTD), which reflects the duration of bolus flow from the ramus of the mandible to the upper esophageal sphincter.

Method

40 normal and healthy subjects had Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Examinations (VFSEs) of 5 ml thin and nectar thick liquids, and puree consistencies. A slow motion and frame by frame analysis was performed. Three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to examine the main effect and interactions, and paired t-tests for the three consistency comparisons.

Results

Older subjects had a significantly longer PTD than younger subjects (p<0.01). In addition, men had significantly shorter PTDs than women (p<0.01). Puree showed a significantly longer PTD than the other two consistencies, regardless of age and gender (p<0.05).

Conclusion

PTD is an indicative of motor weakness in pharyngeal swallowing secondary to aging. In addition, the results supported the assumption that there is a functional difference in pharyngeal swallowing between men and women. It is expected that the results of this study will be used for further investigation of patients with dysphagia.

Go to :

Swallowing, which is an essential part of human functioning, not only helps to take water and nutrients, but also plays an important part in social rituals.

However, patients with dysphagia are restricted from normal swallowing because they have difficulty in controlling the bolus so it does not enter the airway. There are various diseases that cause dysphagia, which commonly occur in all age groups.

Patients with dysphagia may suffer from aspiration pneumonia, malnutrition, dehydration, and various psychosocial difficulties which lead to reduced quality of life.1,2 Patients with dysphagia may or may not be aware of their dysphagia symptoms. Therefore, a formal diagnosis of dysphagia should be conducted for patients in which it is suspected and appropriate treatment should be followed if necessary.3 Swallowing treatment should focus on appropriate physiological understanding of oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal functions during swallowing.

To facilitate understanding and research of swallowing physiology, swallowing is generally divided into four stages: oral preparation, oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal stages. The pharynx is particularly connected with the airway and the esophagus. The pharyngeal stage of swallowing involves safe transfer of the bolus to the esophagus, without it entering the airway, through appropriate muscular actions of the tongue and pharynx. Careful observation in the pharyngeal stage during swallowing examination is critical when assessing swallowing difficulties.3 The following physiological processes occur during the pharyngeal stage of normal swallowing. First, the soft palate closes the nasal passage to prevent the nasal regurgitation. Second, the epiglottis contacts the arytenoid cartilage to close the laryngeal vestibule in order to provide airway protection, while the hyoid and larynx elevate, to further help airway protection and to open the esophagus. The bolus passes through the pharynx, and the pharyngeal muscles force the bolus to the esophagus by descending peristaltic movements. Young and middle-aged adults complete the physiological processes of the pharyngeal stage before the bolus enters the pharynx, which protects the airway efficiently and allows safe transfer of the bolus through the esophagus. However, in the elderly, the bolus enters the pharynx before the physiological processes are completed, which may put them at risk of penetration or aspiration but penetration and aspiration are not observed among the elderly.4-6

Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Examination (VFSE) is commonly used to diagnose dysphagia. VFSE is not only helpful for observing the symptom of dysphagia, such as penetration and aspiration, but also facilitates understanding of the physiological characteristics of swallowing through temporal and biomechanical measurement.4-7 Temporal measurement of swallowing helps to investigate relationships between the movements of the structures and muscles that are involved in swallowing, in addition to the passage of the bolus. Previous temporal measurement of swallowing has focused on the elevation of the hyoid and larynx as well as laryngeal closure related to bolus transfer in the pharynx.8-10 It is important that more research is undertaken to better understand how pharyngeal muscles respond when the bolus moves through the pharynx as well as the physiological process that facilitate bolus transfer.

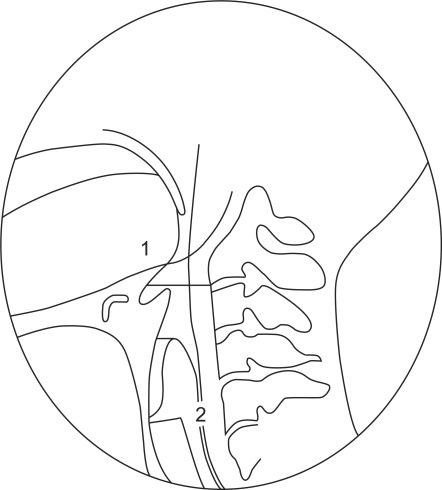

To investigate bolus transfer in the pharynx in normal swallowing, it is essential to understand the role of the oropharyngeal muscles that promote bolus transfer. In addition, future studies could conduct temporal measurement of normal swallowing to better understand patients with dysphagia. Robbins et al.6 proposed using Pharyngeal Transit Duration (PTD) to measure the time from the bolus entering the pharynx to its passing to the upper esophageal sphincter. The starting point of pharyngeal swallowing is taken as when the head of the bolus passes the ramus of mandible. The ending point is when the bolus fully passes through the Upper Esophageal Sphincter (UES) (Fig. 1). Thus, the PTD is the time it takes from the head of the bolus passing the ramus of mandible until the end of the bolus passes the UES. During normal swallowing, it has been found that the PTD is 1 second for young and middle-aged subjects with thin liquid, and 1.5 seconds for the elderly.6,11 Features that affect PTD include the movements of the superior, middle, and inferior constrictors from the top to the bottom of the pharynx, which is known as pharynx peristalsis.3,12 The superior constrictor contacts the tongue base to prevent the bolus from back-flowing to the oral or nasal cavity and force to push the bolus down. The middle constrictor also helps to push the bolus down, while the inferior constrictor is connected with the UES which pushes the bolus to reach and pass through the UES. These pharyngeal constrictors move the bolus down through the pharynx, acting like the piston of a syringe that pushes from top to bottom. In addition, gravity plays an important role in transferring the bolus to the UES, due to its weight. Several studies have reported on PTD during normal swallowing. Robbins et al.6 reported that PTD increases in the elderly during normal swallowing, but it was not found to differ according to gender. Hamlet et al.11 reported that puree had a 1.4 second PDT, whereas thin liquid was lower, at 0.7 seconds.

The purpose of the current study is to examine the effects of age, gender and liquid consistency in normal population swallowing, using PTD as a measure. Three bolus consistencies (thin and nectar thick liquids, and puree) were used to perform VFSE. The results of this study were designed to be used as a control for a follow-up study with post-stroke patients and to help develop diagnosis and treatment of dysphagia.

Go to :

Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Examinations (VFSEs) of 80 healthy subjects, taken between 2000 and 2010,were collected from the Swallowing Research Laboratory at Ohio University.

From these data, this study randomly chose 40 VFSEs in which there was clear observation of the anatomical structure of the oral and pharyngeal cavities. Based on previous studies on normal swallowing, subjects were divided into 20 younger and 20 older subjects, with 10 males and 10 females in each group. The age range of the younger group was 21 to 37, with the mean age at 26.6 (standard deviation 5.49) and of the older group was 61 to 89, with the mean age at 77.25 (standard deviation 8.4).

All subjects underwent clinical examination of the cranial nerves and facial structure, which examined for abnormalities in the nervous system or structures. The examiner was experienced with dysphagia diagnosis. Subjects with abnormal symptoms were excluded. Subjects filled in a questionnaire, which examine their history of dysphagia, nutritional condition, abnormalities in nerve or head and neck structure, cognitive ability and motor ability. This study was approval by the Internal Review Board (IRB) of Ohio University.

Standardized VSFE procedure was applied to all subjects. An x-ray tube was focused on the head and neck of subjects, examining the oral cavity anteriorly, the nasal cavity superiorly, and the pharyngeal cavity inferiorly. Each subject held a cup of 5 ml thin liquid (concentration 14 cP), thick liquid (concentration 187 cP thickened juice) and puree (apple sauce) in his mouth and swallowed the bolus according to instruction.

Water and contrast medium (E-Z-M Barium) powder were mixed for use. Each subject swallowed twice per consistency, with one subject performing a total of six swallows.

All VFSE were digitized and stored electronically. Adobe Premier Pro 1.5 was used to analyze each video-frame (30 frames/second). PTD was measured by the previously stated method.

To observe statistical differences and interactions between independent variables, a three-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. Age, gender, and consistency were the independent variables. Also, paired t-tests were performed to analyze differences between consistencies. To measure the study reliability, eight subjects (20%) were randomly selected. The intrajudge and interjudge reliability (Pearson Correlation Coefficient) were analyzed based on re-analysis of the same subjects. SPSS 16.0 was used to perform allstatistical analysis.

Go to :

All swallows were clinically observed as being within the normal range. Neither penetration nor aspiration was observed. Structural abnormalities in the oral, nasal, pharyngeal and laryngeal structures were not observed during VFSE. Tongue movements, hyolaryngeal elevation, laryngeal airway protection, opening of esophagus sphincter, and other biomechanical movements of swallowing were within the normal range.

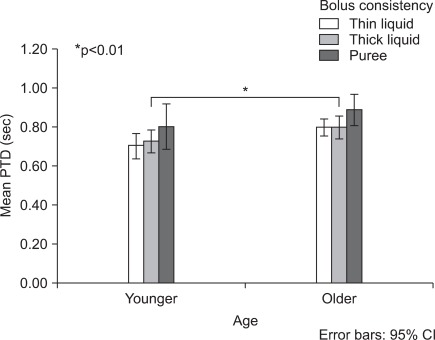

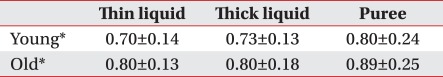

For thin liquid, the younger subjects showed a 0.1 second shorter PTD than did the older subjects. For thick liquid and puree, the younger subjects had 0.07 and 0.09 second shorter PTDs, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 2). There was a significant difference between the younger and older subjects [F (1, 5.73)=8.32, p<0.01]. For all consistencies, the younger subjects showed shorter PTDs than did the older subjects. However, there was no interaction between age and consistency.

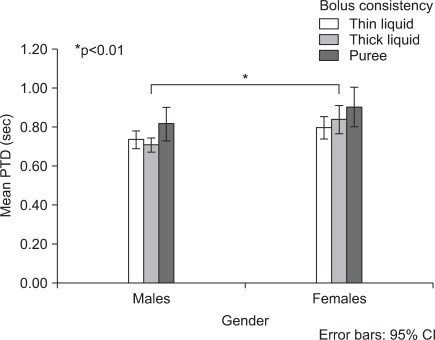

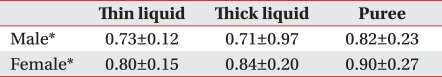

Male subjects had 0.07, 0.13, and 0.08 second shorter PTDs than female subjects for thin liquid, thick liquid and puree, respectively (Table 2, Fig. 3). The two groups showed significant difference [F (1, 5.73)=9.22, p<0.01]. There was no interaction between gender and consistency.

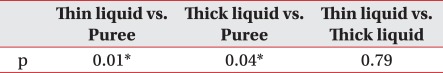

The results of this study not only presented swallowing differences by gender and age but also by consistency. However, there was no interaction between age, gender, and consistency. Paired t-tests were performed to analyze differences among consistencies. There was a significant difference between puree and the two liquid consistencies (p<0.05). There was no significant difference between thin and thick liquids (Table 3).

To measure intrajudge reliability, the principal investigator re-analyzed the x-ray swallowing examinations of 20% of the subjects. There was significant correlation between the first and second measurements (r=0.97, p<0.01). In addition, to assess interjudge reliability, the same 20% of subjects were re-analyzed by the second investigator, who had two years' experience with temporal measurements of swallowing. The results were compared to those of the principal investigator. There was a significant correlation between the two investigators (r=0.91, p<0.01).

Go to :

The purpose of the current study is to examine PTD in normal swallowing during the pharyngeal stage with different bolus consistencies. Subjects were divided by age and gender. Each subject swallowed thin and thick liquid, and puree. The PTD was measured through analysis of the VFSEs.

The results of this study showed that younger subjects had a shorter PTD than their older counterparts. This result is consistent with that of Robbins et al.,6 and is assumed to relate to younger subjects having stronger muscle contraction in the tongue and pharynx. When the bolus passes from the oral cavity to the pharynx during swallowing, the superior constrictor muscle and tongue contact to close the oropharynx and generate force to push the bolus down into the pharynx. Meanwhile, the middle and inferior constrictors perform peristalsis to move the bolus to the esophagus.3,12,13 As age increases, these muscles and their ability to contract weaken.

A longer PTD puts the elderly at higher risk of dysphagia, particularly when a long PTD is concurrent with delayed Stage Transition Duration (STD) during swallowing, which has been commonly observed in the elderly.4-6,8 The STD refers to the time between the bolus entering the pharynx until the initiation of hyoid excursion. Delayed STD leads to a high risk of pharyngeal dysphagia, such as penetration and aspiration. In addition, a long PTD requires the elderly to extend their laryngeal closure as the bolus remains in the pharynx for a longer time. It may be a burden to maintain long hyolaryngeal excursion and to hold the breath for an extended time, and thus a long PTD may make the elderly fatigue easily and lengthen the overall swallowing duration. However, the elderly population has not been found to be more disposed to dysphagia. It is thus necessary to discover how the elderly compensate for their longer PTD. However, they are vulnerable to suffer from stoke, Parkinson's disease or other illnesses. Dysphagia is frequently accompanied with these diseases. Overall, the reduced neuromuscular and sensory functions in the elderly may also put them into the high risk of dysphagia.

Generally, male subjects are supposed to have anatomically longer pharynxes and longer PTD. However, the conflicting result was obtained in this study: PTD was shorter in male subjects than females. It is hypothesized that male subjects utilize more muscle strength in the tongue and pharynx than female subjects. According to Stierwalt and Youmans,14 men showed stronger tongue muscles during swallowing than women. The results of this study supported the theory that men tend to utilize more muscle strength when pushing the bolus toward the esophagus than women do. However, more research, using electromyography or other tools to verify this finding, is necessary. Another interesting finding of this study is that there was no interaction between age and gender. That is, the PTD was shorter in males than females subjects regardless of age.

Regardless of age and gender, the thin and thick liquids had shorter PTDs than puree. Puree, which has a high viscosity, moved slowly in the pharynx, which in turn led to a longer PTD. This result is consistent with those of Robbins et al.6 In addition, this study reported that there was no difference in PTD between the thin and thick liquids. Oommen et al,15 also found no difference between thin and thick liquid in terms of STD and Laryngeal Closure Duration (LCD). That is, consistency difference in PTD was not significant when the bolus comprised nectar-thick liquid, but there was difference with puree consistency. It is necessary to examine PTD when using honey-thick liquid in follow-up research.

PTD in this study was slightly different to the results found by Hamlet et al.11 It is assumed that this difference stems from the bolus volume size during the VFSE and the age of the subjects. Future dysphagia studies should control the bolus volume, and the age and gender of subjects.

Bolus consistency change is commonly used in swallowing management. It is thus essential to determine safe consistencies during VFSE in order to help the patient. It is likewise important to measure temporal characteristics using the PTD when making clinical judgments of patients with dysphagia.

A limitation of this study is that the PTD was measured by using previously collected data. In addition, the investigator instructed subjects to swallow the bolus after having placing it inside the mouth during VFSE. Naturalness of swallowing was not taken into account. This study also investigated a small number of subjects. Future studies should use larger study sizes when attempting to replicate these results.

This study confirmed that the temporal measurement of swallowing helps researchers to understand the pharyngeal transition of the bolus and to understand related swallowing physiology. Future studies should measure the PTD of post-stroke patients who suffer from dysphagia and compare this with normal subjects. Such follow-up studies will contribute to the understanding of dysphagia physiology and the development of related diagnoses and treatment.

Go to :

This study reported that PTD differences occur by age, gender, and bolus consistency in normal populations. The longer PTD found in older subjects is most likely related to the reductions in neuromuscular and sensory function that take place as age increases. It is assumed that male subjects' shorter PTD may be related to the stronger swallowing muscular contraction that occurs in males, compared with females. In addition, the increase in PTD as viscosity increases that this study found could be useful information for determining safe bolus consistency for patients with dysphagia.

Although gender differences in swallowing functions were observed in this study, direct measurement using electromyography or a manometer is required to better understand the role of the pharyngeal muscles during normal swallowing. Temporal measurement of swallowing helps to promote accurate understanding of the physiology of normal swallowing and contributes to developing effective dysphagia diagnosis and treatment.

Go to :

References

1. Langmore SE, Terpenning MS, Schork A, Chen Y, Murray JT, Lopatin D, Loesche WJ. Predictors of aspiration pneumonia: how important is dysphagia? Dysphagia. 1998; 13:69–81. PMID: 9513300.

2. McHorney CA, Bricker DE, Kramer AE, Rosenbek JC, Robbins J, Chignell KA, Logemann JA, Clarke C. The SWAL-QOL outcomes tool fordysphagia in adults: I. Conceptual foundation and item Development. Dysphagia. 2000; 15:115–121. PMID: 10839823.

3. Logemann JA. Evaluation and Treatment of Swallowing Disorders. 1998. 2nd ed. Austin: Pro-Ed;p. 3–5.

4. Logemann JA, Pauloski BR, Rademaker AW, Colangelo LA, Kahrilas PJ, Smith CH. Temporal and biomechanical characteristics of swallow in younger and older men. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2000; 43:1264–1274. PMID: 11063246.

5. Logemann JA, Pauloski BR, Rademaker AW, Kahrilas PJ. Oropharyngeal in younger and older women: videofluoroscopic analysis. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2002; 45:434–445. PMID: 12068997.

6. Robbins J, Hamilton JW, Lof GL, Kempster GB. Oropharyngeal swallowing in normal adults of different ages. Gastroenterology. 1992; 103:823–829. PMID: 1499933.

7. Groher ME. The detection of aspiration and videofluoroscopy. Dysphagia. 1994; 9:147–148. PMID: 8082321.

8. Kim Y, McCullough GH, Asp CW. Temporal measurements of pharyngeal in normal populations. Dysphagia. 2005; 20:290–296. PMID: 16633874.

9. Kim Y, McCullough GH. Stage transition duration in patients poststroke. Dysphagia. 2007; 22:299–305. PMID: 17610013.

10. Power ML, Hamdy S, Singh S, Tyrrell PJ, Turnbull I, Thompson DG. Deglutitive laryngeal closure in stroke patients. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007; 78:141–146. PMID: 17012336.

11. Hamlet SL, Muz J, Patterson R, Jones L. Pharyngeal transit time: assessment with videofluoroscopic and scintigraphic techniques. Dysphagia. 1989; 4:4–7. PMID: 2640176.

12. Seikel JA, King DW, Drumright DG. Anatomy and Physiology for Speech. Language and Hearing. 2005. 3rd ed. New York: Thomson Delmar Learning;p. 197–200.

13. Borgström PS, Ekberg O. Speed of peristalsis in pharyngeal constrictor musculature: correlation to age. Dysphagia. 1998; 2:140–144.

14. Stierwalt JA, Youmans SR. Tongue measures in individuals with normal and swallowing. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2007; 16:148–156. PMID: 17456893.

15. Oommen ER, Kim Y, McCullough G. Stage transition and laryngeal closure in poststroke patients with dysphagia. Dysphagia. 2011; 26:318–323. PMID: 21085995.

Go to :

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download