Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the prevalence and risk factors of peripheral neuropathy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) treated with leflunomide (LEF) by quantitative sensory testing (QST).

Method

A total of 94 patients were enrolledin this study, out of which 47 patients received LEF. The other 47 patients received alternative disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and served as the control group. The demographic characteristics, laboratory findings, concomitant diseases, and medication history were evaluated at the time of QST. The cooling (CDT) and vibratory detection threshold (VDT) as the representative components of QST were measured.

Results

Age, gender, RA duration, ESR, and CRP did not show any significant differences between the two groups. VDT did not demonstrate any significant difference in both groups. However, CDT in LEF group was significantly higher than that of the control group (8.6±2.7 in LEF vs. 5.6±3.8 in control). The proportion of RA patients in the LEF group showing abnormally high CDT was over 2 times greater than that of the control group, but these findings were not statistically significant. Age, RA duration (or LEF medication in LEF group), ESR, and CRP did not show significant correlation with CDT in both groups. VDT significantly correlated with age in both groups.

Conclusion

LEF treatment in patients with RA may lead to abnormal CDT in QST. CDT value was not affected by age, RA duration, disease activity, or LEF duration. It remains to be determined whether QST may be a valuable non-invasive instrument to evaluate the early sensory changes in patients with RA taking LEF.

Leflunomide (N-(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)-5-methylisoxazol-4-carboxamide, LEF) is absorbed through the intestinal walls and converted into A77 1726 in the liver, inhibiting dihydrooratate dehydrogenase which is required for biosynthesis of pyrimidine nucleotide by T lymphocytes.1 Then, it inhibits the production of tumor necrosis factor, interleukin 1, reactive oxygen radicals and matrix metalloproteinase 3 in synovial cells.2,3

According to treatment guidelines of American College of Rheumatology, LFE is, together with methotrexate (MTX), recommended as the primary drug for rheumatoid arthritis (RA), regardless of disease duration or activity, and combination therapy with biological products is also recommended if LEF monotherapy does not work.4 Adverse events of LEF such as diarrhea, liver toxicity, alopecia, rash, hypertension and drug induced pneumonia have been known5-9 however, some cases have recently reported peripheral polyneouropathic symptoms such as tingling sensation, paresthesia and motor weakness.10-12 In a nerve conduction study (NCS) on patients that complained of peripheral neuropathic symptoms after LEF administration, it was found that such symptoms were not associated with the NCS results and it was similar to that observed in patients with diabetes mellitus who are normal with regards to NCS results but have pain, as well as signs and symptoms of nerve injury.13,14 This may be because NCS is the test that is usedto determine the function of large myelinated fibers. On the other hand, quantitative sensory testing (QST) is the test that quantifies the threshold of vibration and thermal sensation so that it may distinguish the function of large myelinated fibers from that of small myelinated fibers and unmyelinated fibers as well as determine the function of large myelinated fibers. Therefore, QST is used to diagnose diverse neuropathies and also complements NCS for diagnosis of diabetic neuropathy that is normal for NCS results.15

In this study, we used QST to determine whether there is LEF-induced peripheral nerve injury and to attempted to elucidateits risk factors, in order to provide a key for RA treatment decisions.

This study was approved by Hanyang University Hospital's Institutional Review Board (IRB). We studied 47 patients that met the RA diagnostic criteria16 published by American College of Rheumatology in 1987 and who received LEF (the treatment group). As the control group, another 47 patients with RA were selected that did not take LEF, were treated with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD) and whose sex, age and disease duration were similar to the treatment group.

Before QST, a survey was performed to evaluate the sex, age, tingling sensation, disease duration of RA, medication in the last 6 months, concomitant disease, history of anticancer therapy, ESR, CRP, and the positive rate of rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-CCP antibody in both groups. In addition the duration of LEF administration in the treatment group was also determined. Next we examined ESR and CRP as blood markers reflecting disease activity of RA. The whole number of normal ESR was reported and 0.15 mg/dl where less than 0.3 mg/dl of CRP was reported. To investigate other reasons which may cause peripheral neuropathy, we studied the history of anticancer therapy and of administration of statin drug, losartan, isoniazid, warfarin and tamoxifen as well as DMARD (hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, MTX, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor), corticosteroid and NSAIDs; for concomitant diseases, and examined the history of diabetes and thyroid disorders.17

QST was performed on the back of the left hand by using CASE IV QST system (WR Medical Electronics Co., Stillwater, USA) and the test room was maintained at 21-23℃. Vibratory detection threshold (VDT) was measured reflecting the function of large myelinated fibers, and cooling detection threshold (CDT) reflecting that of small myelinated fibers or unmyelinated fibers.

The measurement of CDT and VDT has been described in detail previously by Lee and Kim18 Briefly, for CDT, a stimulator (10 cm2 of area) was attached on the dorsum of the first metacarpal of the left hand and the subject pressed either a 'yes' or 'no' button for what they recognized when pyramid type cold stimulation (25 steps) was given. Just noticeable difference (JND) which is the minimal difference when the subject differentially recognizes two stimulations of similar intensity was defined as the stimulation intensity. Readings started from 13 JND (medium intensity) and the maximum intensity was given for 10 seconds at 8℃, which is not harmful to the human body. According towhether the subject recognized the initial stimulation, JND was increased or decreased by 4, and was changed by 2 and 1 in the second and third stimulation, respectively. In this way, 25 steps of stimulation were given through 4-2-1 stepping algorithm, regardless of its order. Of these, 5 stimulations were described as fakes. The detection threshold was the mean of turning points that 1 JND increased or decreased in the 4-2-1 stepping algorithm.

For VDT, a vibrator of vibration transmitter was attached on the dorsum of distal interphalangeal jointof the left hand middle finger, and 125 Hz of sine-wave vibrations (25 steps) were given to the subject. According to whether the subject noticed vibration, the intensity was measured through a 4-2-1 stepping algorithm, as mentioned above.18 In case of less than 1 JND, it could be considered as 0 that the subject does not recognize any difference between stimulations; however, it was considered as 0.9 for conservative analysis.

We carried out QST on both hands in 46 of the total of 47 patients in the control group; CDT and VDT was measured on both hands and was highly correlated. Therefore, QST was performed on the left hand in the LEF treatment group.

To compare CDT, BDT and other clinical findings between the treatment and control groups, we used Mann-Whitney rank sum test and conducted chi-square or Fisher Exact test to analyze the difference in the number of patients (normal vs. abnormal). Pearson correlation analysis was used to examine the correlation between CDT and VDT, as well as disease duration of RA, duration of LEF administration, and ESR or CRP. To analyze the effect of LEF administration history on CDT and VDT while calibrating the effect of other variables, analysis of covariance was used. SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) was used for these statistical tests, and p<0.05 level of statistical significance was applied.

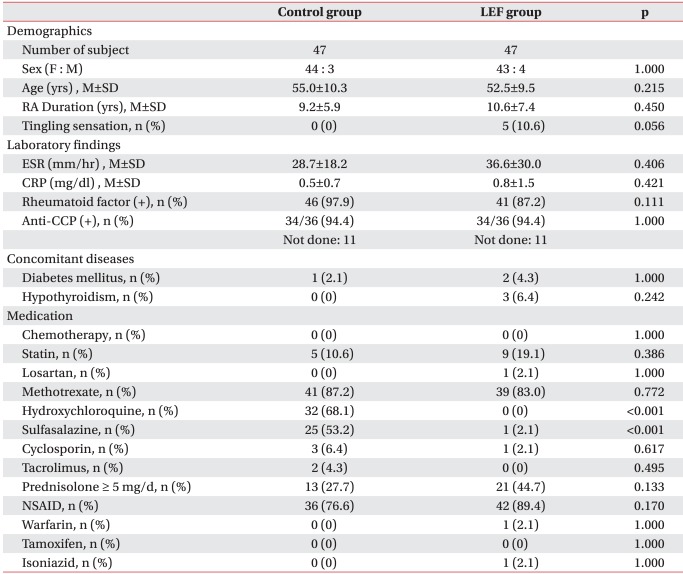

In the treatment group, the mean age was 52.5 years old; 43 females and 4 males; 10.6 years of the mean disease duration; and, 36.6 mm/hr and 0.8 mg/dl of ESR and CRP, respectively. In the control group, the mean age was 55.0 years old; 44 females and 3 males; 9.2 years of the mean disease duration; 28.7 mm/hr and 0.5 mg/dl of ESR and CRP, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in the positive rate of RF and anti-CCP antibody, concomitant disease, and the ratio of corticosteroid andNSAIDs administration over 5 mg daily (Table 1). There were 5 patients with tingling sensation in the treatment group; they complained of mild symptom intensity on their hand and foot and their CDTs were normal, whereas two of them showed higher range of VDT.

In case of DMARD administration in the last 6 months before QST, the control group received medication other than LEF; hydroxychloroquine and sulfasalazine were widely used. The ratio of MTX administration was similar in both groups. Besides, no statistically significant difference was observed in the administration ratio of statin drug, anticancer drug, losartan, isoniazid, warfarin and tamoxifen between the two groups.

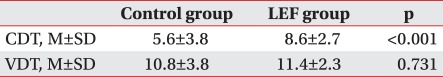

The mean VDT of the treatment and control groups were 10.8±3.8 and 11.4±2.3, respectively; no significant difference was observed between two groups (p=0.731). On the other hand, the mean CDT of the treatment group was 8.6±2.7, significantly higher than that of the control group (5.6±3.8) (p<0.001) (Table 2).

Based on the normal CDT range (7.3±3.3) measured in the same way in the Korean healthy control group by Lee and Kim,18 there were 11 patients (23.4%) with abnormal CDT in the treatment group who showed more than 10.6 of CDT; it was higher than that in the control group (4 patients, 8.5%) - no statistically significant difference was observed (p=0.089).

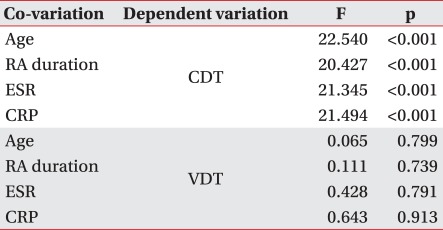

In Pearson correlation analysis to examine the effect of age, disease duration of RA, duration of LEF administration, ESR and CRP on VDT and CDT in both groups, a significant correlation was observed only between age and VDT in both groups (controlgroup; r=0.396, p=0.00581, LEF treatment group; r=0.310, p=0.0337). With analysis of covariance to calibrate the possible effect of age, disease duration of RA, and ESR and CRP (representing the degree of inflammatory response) on peripheral nerves of RA patients, individual covariants were set and there was a significant difference in CDT between the two groups, but not in VDT (Table 3).

LEF was approved by US FDA in September 1998 and is a type of DMARD with an efficiency similar to MTX. Its adverse events include diarrhea, liver toxicity, hypertension, rash, alopecia and drug induced pneumonia;5-9 however, in post marketing survey, peripheral polyneuropathy was not been reported. In 2002, Carulli and Davies first reported the occurrence of peripheral neuropathy related to LEF in two patients,19 and subsequently, several case reports were published abroad;10-12 in Korea, Kim et al.,20 first reported LEF-caused peripheral polyneuropathy in 2008.

After several case reports were presented, a cohort study was performed, demonstrating that LEF induces peripheral neuropathy.3,21 It has been known that LEF inhibits the biosynthesis of uridine which is important in phase II conjugation such that it leads to the accumulation of toxic metabolites in the body, causing LEF-induced neuropathy.2,22 Symptoms appear after 6-10 months of administration on average.21 In case of LEF-induced peripheral polyneuropathy, however, clinical symptoms are unrelated to NCS results, suggesting that NCS is not sufficient to diagnose it.13,14

The most important aspects in diagnosis of peripheral polyneuropathy are clinical symptoms and physical findings. These are subjective and qualitative, which is why NCS, being objective and quantitative,has been widely used. NCS mostly presents the function of large myelinated fibers; therefore, it does not correctly measure various neurotic symptoms that commonly occur by dysfunction of smallmyelinated or unmyelinated fibers in patients with polyneuropathy. In comparison, QST concurrently measures both thermal and vibration sensation and complement NCS.18

In this study, the mean CDT (8.6±2.7) in the treatment group was significantly higher than that (5.6±3.8) in the control group. This suggests the possibility that small myelinated or unmyelinated fibers which are in charge of thermal sensation are damaged in the treatment group, compared to the control group. Based on the normal CDT range (7.3±3.3) of 22 healthy people (mean age: 45.9±10.1; male : female=12 : 10) measured in the same way by Lee and Kim,18 the number of patients that are higher than the normal CDT range in the treatment group was more than twofold compared to the control group. However, no statistically significant difference in Fisher exact test was observed. Thus, as described in this study, the treatment group showed higher mean CDT and more patients measured in the abnormal range, compared to the control group. However, it is hard to say that there may be more patients with peripheral neuropathy in the treatment group. It is required to assure the meaningfulness of QST by comparing with RA patients who do not receive DMARD or healthy people. Also, 10.6 of CDT which is the lower limit of abnormally high CDT range is not the cut-off value obtained from receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, but is greater than standard deviation by 2 on average. This could be very conservative for abnormality which implies we may consider the possibility of lower difference in the ratio of abnormal vs. normal range between the two groups. Furthermore, the cut-off value for individual sensory thresholds in QST needs to be assessed by using ROC curve.

There was no significant difference in VDT between the two groups, suggesting that there may be less possibility that large myelinated fibers that are in charge of vibration are damaged. No significant difference in VDT between two groups is similar to previous results that NCS has a limitation in diagnosis of LEF-induced neuropathy. It is thought that NCS or VDT are used to evaluate the function of large myelinated fibers and that LEF does not affect large myelinated fibers.

The duration of LEF administration did not affect CDT and there was no significant correlation between CDT and age, disease duration of RA and RA disease activity in both groups. This demonstrates that the accumulation of LEF-induced peripheral nerve injury does not happen as the administration duration, disease duration of RA or RA disease activity is increased. Such a result is similar to that of a previous study, in which it was shown that disease duration of RA and duration of LEF administration are not risk factors causing neuropathy in LEF-administered patients; however, it is different from the finding that old age is the risk factor.21

In this study, the small sample size is a limitation by; however, the difference in results between two groups is reliable because QST is used to quantify and compare the mean values. It may be necessary for further study to increase the sample size to calculate the prevalence rate of LEF-induced peripheral polyneuropathy and to perform both NCS and QST to provide accurate diagnostic standards for LEF-induced peripheral polyneuropathy.

Where LEF is administered to RA patients, it may lead to abnormal results of QST, especially CDT. This means that there is the possibility of LEF-induced peripheral polyneuropathy, which It is not affected by disease duration of RA, RA disease activity and duration of LEF administration. Further study may be necessary to determine whether QST is useful for the diagnosis of LEF-induced peripheral polyneuropathy.

References

1. Breedveld FC, Dayer JM. Leflunomide: mode of action in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2000; 59:841–849. PMID: 11053058.

2. Elkayam O, Yaron I, Shirazi I, Judovitch R, Caspi D, Yaron M. Active leflunomide metabolite inhibits interleukin 1beta, tumor necrosis factor alpha, nitric oxide and metalloproteinase-3 production in activated human synovial tissue cultures. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003; 62:440–443. PMID: 12695157.

3. Palmer G, Burger D, Mezein F, Magne D, Gabay C, Dayer JM, Guerne PA. The active metabolite of leflunomide, A77 1726, increases the production of IL-1 receptor antagonist in human synovial fibroblasts and articular chondrocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004; 6:R181–R189. PMID: 15142263.

4. Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, Anuntiyo J, Finney C, Curtis JR, Paulus HE, Mudano A, Pisu M, Elkins-Melton M, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008; 59:762–784. PMID: 18512708.

5. Kremer JM, Cannon GW. Benefit/risk of leflunomide in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2004; 22(5 suppl 35):S95–S100. PMID: 15552521.

6. van Riel PL, Smolen JS, Emery P, Kalden JR, Dougados M, Strand CV, Breedveld FC. Leflunomide: a manageable safety profile. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2004; 71:21–24. PMID: 15170904.

7. van Roon EN, Jansen TL, Houtman NM, Spoelstra P, Brouwers JR. Leflunomide for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in clinical practice: incidence and severity of hepatotoxicity. Drug Saf. 2004; 27:345–352. PMID: 15061688.

8. Rozman B, Praprotnik S, Logar D, Tomsic M, Hojnik M, Kos-Golja M, Accetto R, Dolenc P. Leflunomide and hypertension. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002; 61:567–569. PMID: 12006342.

9. Ito S, Sumida T. Interstitial lung disease associated with leflunomide. Intern Med. 2004; 43:1103–1104. PMID: 15645640.

10. Metzler C, Arlt AC, Gross WL, Brandt J. Peripheral neuropathy in patients with systemic rheumatic diseases treated with leflunomide. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64:1798–1800. PMID: 16284351.

11. Martin K, Bentaberry F, Dumoulin C, Longy-Boursier M, Lifermann F, Haramburu F, Dehais J, Schaeverbeke T, Begaud B, Moore N. Neuropathy associated with leflunomide: a case series. Ann Rheum Dis. 2005; 64:649–650. PMID: 15769926.

12. Kho LK, Kermode AG. Leflunomide-induced peripheral neuropathy. J Clin Neurosci. 2007; 14:179–181. PMID: 17107800.

13. Richards BL, Spies J, McGill N, Richards GW, Vaile J, Bleasel JF, Youssef PP. Effect of leflunomide on the peripheral nerves in rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med J. 2007; 37:101–107. PMID: 17229252.

14. American Diabetes Association American Academy of Neurology. Consensus statement: Report and recommendations of the San Antonio Conference of Diabetic Neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 1988; 11:592–597. PMID: 3060328.

15. Dyck PJ, Bushek W, Spring EM, Karnes JL, Litchy WJ, O'Brien PC, Service FJ. Vibratory and cooling detection threshold compared with other tests in diagnosing and staging diabetic neuropathy. Diabetes Care. 1987; 10:432–444. PMID: 3622200.

16. Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, Healey LA, Kaplan SR, Liang MH, Luthra HS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988; 31:315–324. PMID: 3358796.

17. Bonnel RA, Graham DJ. Peripheral neuropathy in patients treated with leflunomide. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004; 75:580–585. PMID: 15179412.

18. Lee SM, Kim BJ. Diagnostic usefulness of quantitative sensory test in diabetic polyneuropathy: comparison with nerve conduction study. J Korean Neurol Assoc. 1999; 17:106–111.

19. Carulli MT, Davies UM. Peripheral neuropathy: an unwanted effect of leflunomide? Rheumatology. 2002; 41:952–953. PMID: 12154221.

20. Kim HC, Jun JB, Lee KA, Kim D, Kim HS, Kim SH. A case of peripheral neuropathy in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis treated with leflunomide. J Korean Rheum Assoc. 2008; 15:273–276.

21. Martin K, Bentaberry F, Dumoulin C, Miremont-Salame G, Haramburu F, Dehais J, Schaeverbeke T. Peripheral neuropathy associated with leflunomide: is there a risk patient profile? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007; 16:74–78. PMID: 16845649.

22. Fox RI, Herrmann ML, Frangou CG, Wahl GM, Morris RE, Strand V, Kirschbaum BJ. Mechanism of action for leflunomide in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Immunol. 1999; 93:198–208. PMID: 10600330.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download