Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of prolonged inpatient rehabilitation therapy in subacute stroke patients.

Method

We enrolled 52 subacute stroke patients who had received 3 months of inpatient rehabilitation therapy. Thirty stroke patients received additional inpatient rehabilitation therapy for 3 months and 22 control patients received only home-based care. The evaluation was measured at 3 and at 6 months after stroke occurrence. Functional improvement was measured using the modified motor assessment scale (MMAS), the timed up and go test (TUG), the 10-meter walking time (10 mWT), the Berg balance scale (BBS) and the Korean-modified Barthel index (K-MBI). The health-related quality of life was evaluated using the medical outcome study, 36-item short form survey (SF-36).

Results

In the experimental group, significant improvements were observed for all parameters at 6 months (p<0.05). However, significant improvements were observed only in MMAS, BBS, and K-MBI at 6 months in the Control group (p<0.05). In comparing the 2 groups, significant difference were observed in all parameters (p<0.05) except 10 meter walking time (p=0.73). The improvement in SF-36 was meaningfully higher in experimental group compared to control group.

More than 60% of the surviving stroke patients have persistent neurological deficits, with various physical disabilities. Stroke requires acute phase treatments with intensive rehabilitation therapy to recover activities of daily living.1-3 Factors affecting the functional recovery after stroke include the rehabilitation therapy, the treatment starting time, and the degree and period of treatment.4 Kwon et al.5 reported that comprehensive rehabilitation therapy plays a critical role in the recovery of walking and daily living functions in stroke patients.

Understanding the neurological and functional recovery after stroke can assist in the establishing of a rehabilitation therapy plan and in the prediction of a prognosis.6 In most cases, the recovery of motor function and daily living function are achieved within the first month, but most stroke patients have persistent disabilities of motor and function. Some studies report that at 6 months after stroke, only 60% of patients are able to make simple daily activities, such as using the bathroom and walking short distances.6,7 Wade et al.8 reported that neurological recovery occurs fastest in the first 2 weeks and most functional recovery occurs within the first 3 months, although complete functional recovery occurs slowly over 6 to 12 months. Prescott et al.9 reported that the recovery of basic motor functions and activities of daily living happens slowly over a period of about 4 months. In contrast to the importance of active rehabilitation therapy in the acute phase until 3 months after onset, understanding and interest in rehabilitation therapy for residual disabilities in the subacute phase is insufficient. Considering that the purpose of rehabilitation therapy is to maintain the independent daily living,10 continuing intensive rehabilitation therapies even after the initial 3 months will bring long-term benefits to functional independence and improvement in the quality of life for stroke patients. Domestic studies on the effects of prolonged inpatient rehabilitation therapy of stroke patients after the acute phase have been insufficient. In this study, we evaluated the effect of prolonged inpatient rehabilitation therapy in subacute stroke patients by comparing a group of stroke patients who received an additional 3 months of inpatient rehabilitation therapy, in the subacute phase after acute rehabilitation therapy and another group who received only home-based care after acute rehabilitation therapy. In line with such aims, we measured the ability to perform activities of daily living, improvements in ability to walk, and quality of life.

The subacute rehabilitation therapy group included 30 subacute stroke patients who were receiving additional 3 months inpatient rehabilitation therapy in another rehabilitation hospital after 3 months acute rehabilitation. The control group included 22 patients who were discharged after 3 months acute rehabilitation and thereafter received only home based care for 3 months. The subject group consisted of stroke patients with first-attack ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke and had a perception function of 16 points or higher on the Korean mini-mental state examination (K-MMSE) score which had been universally applied in similar studies, and could walk 10 m with or without aids and assistance from others. We excluded patients presenting with the following: severe cognitive impairment or aphasia (unable to understand instructions), patients with uncontrolled hypertension or orthostatic hypotension and patients with underlying diseases such as cardiovascular disease or heart failure.

The subacute rehabilitation therapy group was evaluated after the acute rehabilitation therapy at 3 months after stroke onset and after additional 3 months inpatient rehabilitation therapy at 6 months after stroke onset. The control group was also evaluated after the acute rehabilitation therapy at 3 months after stroke onset and after 3 months of home-based care.

We evaluated motor function using the modified motor assessment scale (MMAS) excluding the upper limbs, and also evaluated balance and walking abilities using the Berg Balance Scale (BBS), 10 m Walking Test (10 mWT), and the Timed Up & Go Test (TUG). The activities of daily living function was evaluated using the Korean-modified Barthel index (K-MBI), which consisted of 10 evaluation items (personal hygiene, bathing, feeding, toilet use, stairs, dressing, bowels, bladder, and walking). The quality of life was evaluated using the medical outcome 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36).

We used SPSS 14.0 to analyze the data. Physical changes after stroke onset were evaluated using the paired sample t-test, comparing changes at 3 months and at 6 months after stroke. The comparison of the 2 groups, the independence t-test was used to evaluate the changes at 6 months after stroke onset according to the additional inpatient rehabilitation therapy. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

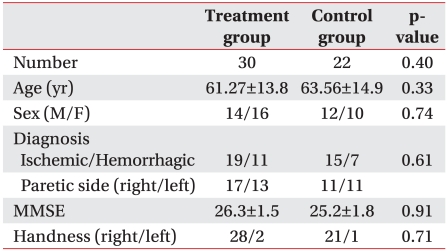

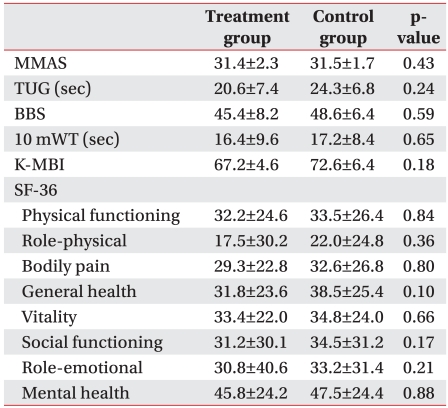

Of the 52 subacute stroke patients, 34 were ischemic stroke patients and 18 were hemorrhagic stroke patients. The brain lesions were on the right cerebral hemisphere for 28 patients and on the left cerebral hemisphere for 24 of the patients. Regarding their main hands, the numbers of right-handed and left-handed patients were 28 and 2 respectively for the treatment group and 21 and 1 for the control group, respectively. No statistically significant difference was observed in age or sex between the 2 groups (Table 1). No significant differences in the functions and quality of life at 3 months after stroke onset between the 2 groups (p>0.05) (Table 2).

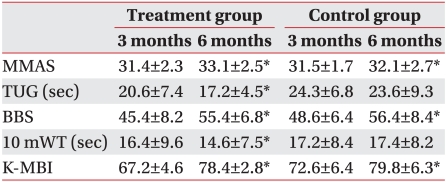

Motor function: The MMAS showed significant improvement 6 months after stroke onset for both groups. The subacute rehabilitation therapy group showed more improvement compared to the control group (p<0.05) (Table 3).

Balance and walking ability: TUG improved significantly 6 months after stroke onset in the subacute rehabilitation therapy group (p<0.05). However, no significant improvement was observed in the control group (Table 3). The BBS significantly improved 6 months after stroke onset for both groups. The subacute rehabilitation therapy group showed more improvement compared to the control group (p<0.05) (Table 3). The 10 mWT significantly improved 6 months after stroke onset in the subacute rehabilitation therapy group, but no significant improvement was observed in the control group (Table 3).

Activities of daily living: Korean-modified Barthel index (K-MBI) significantly improved 6 months after stroke onset for both groups. The subacute rehabilitation therapy group showed more improvement compared to the control group (p<0.05) (Table 3).

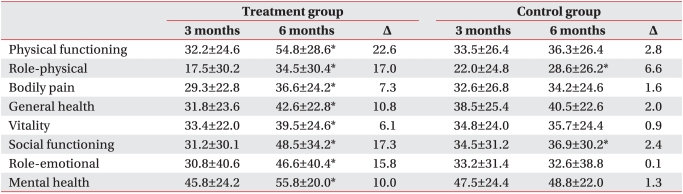

Quality of life: All items in the SF-36 significantly improved in the subacute rehabilitation treatment group, but only role-physical and social functioning items improved in the control group (p<0.05) (Table 4).

This study found that prolonged rehabilitation therapy for subacute stroke patients improved their balance, walking ability, ability to perform activities of daily living, and quality of life compared with the control group.

This shows that prolonged rehabilitation therapy, even after the first 3 months during which time most functional recovery occurs, can be helpful for improving motor ability, function, and quality of life.

Stroke is a major cause of physical disabilities.2,3 Most stroke patients recover for several months after onset, but physical disabilities continue in more than 50% of cases.11 Therefore, it is critical for stroke patients to improve their ability to perform activities of daily living through rehabilitation therapy. Contrary to the findings of this study, Verheyden et al.11 claimed that the majority of motor and functional recoveries occur between 1 week and 1 month after onset, and the degree of recovery diminishes from month 1 and month 3. Furthermore, Verheyden et al reported that functional improvements could be expected and no improvement in the Barthel index was observed in 50% of the patients between 3 months and 6 months after stroke onset. Skilbeck et al.10 reported that the recovery of stroke in neurological deficit and activities of daily living is nearly completed within 3 months after onset, and no great functional recovery happens after this time period. Many of these studies report that most motor and functional recovery happens in the first 3 months after stroke onset, but it is difficult to accurately understand how long functional recovery can be expected to last. It is known that the reorganization and compensatory mechanism of the brain by neuroplasticity is involved in the recovery after brain damage.12 The change in the cerebral cortex by the neuroplasticity of the brain does not occur by repetition of simple motions, but the compensation for motor paralysis occurs by repeated motor learning.12,13 Studies demonstrating improvements in the ability of chronic stroke patients to walk suggest the continued recovery mechanism of the brain through its neuroplasticity and compensation mechanism, even in chronic brain injuries.13 Thus, continued intensive rehabilitation therapy in subacute stroke patients, who are in the process of neurological recovery is expected to bring about greater functional recovery. Considering that the goal of stroke rehabilitation is independent daily living through the acquisition of maximum functioning, to actively prolong rehabilitation therapy even after completing the acute phase of rehabilitation therapy would contribute to improving stroke patients' quality of life and independent daily living.

Mayo et al.14 reported that when a group received prolonged inpatient rehabilitation therapy after the acute phase treatment was compared with another group that had received a visiting rehabilitation program at home, the latter group showed higher scores in improvements to activities of daily living and quality of life. However, Chiu et al.15 reported that stroke patients who received care at nursing facilities showed greater improvement in economic and activities of daily living than those who received care at home. Although these studies are different from the present study, they showed the importance of continued rehabilitation therapy by demonstrating that continued rehabilitation treatment, brought about improvements in activities of daily living without hospitalization.

In the findings of this study, the inpatient rehabilitation therapy group in subacute stroke patients showed significant improvement in all items. The control group showed significant improvements in MMAS, BBS, and K-MBI, which indicated improvements in motor functions, balancing, and activities of daily living. This result suggests that functional recovery can happen as a natural neurological deficit recovery, performance of daily living at home can provide some treatment effects, and many other factors are involved in the function recovery in addition to the rehabilitation therapy. When the 2 groups were compared, however, the subacute rehabilitation therapy group showed greater recovery than the control group, probably because of the greater compensation mechanism for motor paralysis by repeated motor learning among the recovery mechanisms after brain injury.

Many factors that affect the quality of life of stroke patients have been reported. King16 reported that the functional condition of patients after stroke affected their quality of life. Osberg et al.17 reported that the lower the daily living functioning of patients, the lower the quality of life or satisfaction. A study on the quality of life of hemiplegic patients after stroke in Korea reported that the quality of life was higher as their dependence on activities of daily living was lower, their restriction of communication was fewer, and they were less depressed. The type of stroke and location of the lesion had no influence on the quality of life of stroke patients.18 In this study, the inpatient rehabilitation therapy group showed significantly higher scores in total averages, physical health scores, and mental health scores than the control group. This result seems to be a secondary effect of psychological support and motivation for treatment through the therapeutic environment, as well as improvement in their activities of daily living and walking ability.

This study had several limitations. The number of subjects was small and the patients were able to communicate because they had not received serious damage to their cognitive ability. The patients could walk 10 m, therefore they do not represent all hemiplegic stroke patients. Furthermore, this study did not evaluate improvements in upper limb functioning though the proper method for evaluating the effects of rehabilitation therapy was to consider the functions of both upper and lower limbs. In addition, no basis was presented for long-term inpatient rehabilitation therapy for chronic patients 6 months or more after onset. Therefore, more systematic studies will be needed with an increase in the number of subjects, inclusion of the evaluation of upper limb functions, and additional examination of long-term treatment effects of the prolonged inpatient-rehabilitation therapy approach after acute phase rehabilitation are needed in the future.

This study observed that the subacute rehabilitation therapy group, who were received additional inpatient rehabilitation therapy for 3 months, showed a significant improvements in activities of daily living, balance and walking ability, and quality of life compared to the control group who were received only home-based care. Therefore, prolonged inpatient rehabilitation therapy must be considered in order to achieve functional improvements and an enhanced quality of life in the subacute phase.

References

1. Werner RA, Kessler S. Effectiveness of an intensive outpatient rehabilitation program for postacute stroke patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1996; 75:114–120. PMID: 8630191.

2. Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Fiedler RC. Discharge outcome after stroke rehabilitation. Stroke. 1992; 23:978–982. PMID: 1615548.

3. Lehmann JF, DeLateur BJ, Fowler RS Jr, Warren CG, Arnhold R, Schertzer G, Hurka R, Whitmore JJ, Masock AJ, Chambers KH. Stroke rehabilitation: outcome and prediction. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1975; 56:383–389. PMID: 809023.

4. Choi YN, Park SW, Choi SA, Son MO, Lee HS, Jung SN, Lee KB, Jang SJ, Kim BS. Long-term effects of day hospital program in stroke rehabilitation. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2005; 29:9–14.

5. Kwon YW, Lee JM, Jeon JY, Choi JH, Kwon DY, Lee KW. Comparison of functional recovery status according to rehabilitation therapy in stroke patients. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2002; 26:370–373.

6. Patel At, Duncan PW, Lai SM, Studenski S. The relation between impairments and functional outcomes poststroke. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000; 81:1357–1363. PMID: 11030501.

7. Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ahmed S, Gordon C, Hiqquins J, McEwen S, Salbach N. Disablement following stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 1999; 21:258–268. PMID: 10381238.

8. Wade DT, Wood VA, Hewer RL. Recovery after stroke-the first 3 months. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985; 48:7–13. PMID: 3973623.

9. Prescott RJ, Garraway WM, Akhtar AJ. Predicting functional outcome following acute stroke using a standard clinical examination. Stroke. 1982; 13:641–647. PMID: 7123597.

10. Skilbeck CE, Wade DT, Hewer RL, Wood VA. Recovery after stroke. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1983; 46:5–8. PMID: 6842200.

11. Verheyden G, Nieuwboer A, De Wit L, Thijs V, Dobbelaere J, Devos H, Severijns D, Vanberen S, De Weerdt W. Time course of trunk, arm, leg, and functional recovery after ischemic stroke. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008; 22:173–179. PMID: 17876069.

12. Krakauer JW. Motor learning: its relevance to stroke recovery and neurorehabilitation. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006; 19:84–90. PMID: 16415682.

13. Jung KH, Ha HG, Shin HJ, Ohn SH, Sung DH, Lee PK, Kim YH. Effects of robot-assisted gait therapy on locomotor recovery in stroke patients. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 2008; 32:258–266.

14. Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Cote R, Gayton D, Carlton J, Buttery J, Tamblyn R. There's no place like home: an evaluation of early supported discharge for stroke. Stroke. 2000; 31:1016–1023. PMID: 10797160.

15. Chiu L, Shyu WC, Liu YH. Comparisons of the cost-effectiveness among hospital chronic care, nursing home placement, home nursing care and family care for severe stroke patients. J Adv Nurs. 2001; 33:380–386. PMID: 11251725.

17. Osberg JS, DeJong G, Haley SM, Seward ML, McGinnis GE, Germaine J. Predicting long-term outcome among post-rehabilitation stroke patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1988; 67:94–103. PMID: 3377892.

18. Kwon HK, Oh CH. Clinical study of stroke. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 1984; 8:83–91.

19. Hesse S, Bertelt C, Jahnke MT, Schaffrin A, Baake P, Malezic M, Mauritz KH. Treadmill training with partial body weight support compared with physiotherapy in nonambulatory hemiparetic patients. Stroke. 1995; 26:976–981. PMID: 7762049.

20. Pyun SB, Kim SH, Hahn MS, Kwon HK, Lee HJ. Quality of life after stroke. J Korean Acad Rehabil Med. 1999; 23:233–239.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download