INTRODUCTION

Depressive disorders are the most common psychological problems in spinal cord injury (SCI) patients.

1 The severity of depression ranges from minor depression to adjustment disorders and major depressive episodes. Their type, duration, pervasiveness of symptoms, and effect on functions are variable. However, even subclinical levels of depression have been found to have a major impact on health, activities of daily living, and interpersonal relationships with nondisabled people.

2

The estimated prevalence of depression after SCI varies from study to study, depending on the type of measurement, the definition of depression, and the period during which the measurement was actually taken. The rates of clinically significant symptoms range from approximately 14% to 35%, and major depression has been reported in 10% to 15% of people with SCI.

3

A better quality of life (QOL) is the ultimate goal of rehabilitation. QOL is a key outcome measure following the SCI,

4 and psychological issues such as stress are known to have correlations with the QOL. The heightened stress levels in individuals with SCI further decrease their QOL.

5 The changes in resilience as a result of the SCI are also believed to have correlation with satisfaction of life, onset of depression, and functional independence during inpatient rehabilitation after an SCI.

6

Most of the earlier studies comprised patients who were investigated 1 year after the injury. A few studies investigated the psychological aspects within the 1-year span. The psychological variables are important parameters that can affect functional independence, making evaluation necessary in early periods of rehabilitation.

7

Our goal in this study was to evaluate the severity of depression, degree of life satisfaction, level of stress, and resilience among patients during the first 6 months after the SCI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

This study was conducted in patients with SCIs admitted to the Department of Rehabilitation Medicine between 2007 and 2008. All patients had sustained the SCI during the last 6 months before the commencement of this study.

The inclusion criteria required that the participants be older than 15 years at the time of injury and that they have no previous psychological history. Only patients who voluntarily agreed to participate in this study were included.

Methods

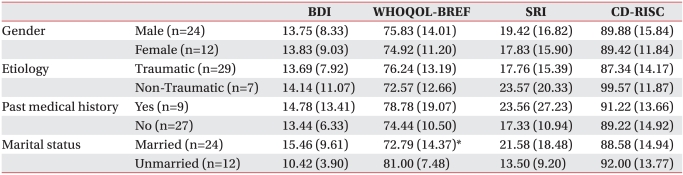

A questionnaire survey was conducted on all the participants, which comprised questions regarding basic information about the patients, and assessment of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF), Stress Response Inventory (SRI) and Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Basic information of the patient detailed age, sex, type of spinal cord injury (level of injury, completeness of injury), etiology of injury and length of time since sustainment of injury up to the date of the survey were studied.

Each subject underwent physical and neurological examinations from a rehabilitation doctor. Neurologic injury was classified using the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury developed by the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA).

Patients capable of filling out the questionnaires completed them by themselves, and patients who were incapable of filling them out due to upper limb weakness were assisted by an accompanying caregiver.

Measures

Depression was measured using the BDI, a 21-question multiple-choice self-report inventory, which is one of the most commonly used instruments in research and practice to measure the presence and severity of depression.

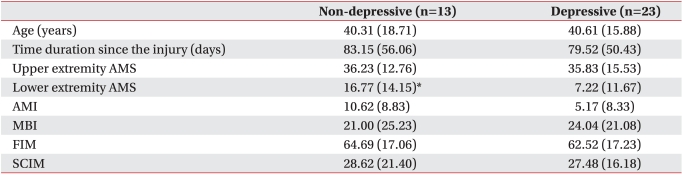

8 We used the cut-scores according Kendall et al. with 0-9 indicating normal, 10-19 indicating mild depression, 20-30 indicating moderate depression, and 31-63 indicating severe depression. The patients who scored 9 or lesser were termed the "non depressive group," and those who scored 10 or more were termed the "depressive group."

9

QOL was measured using the WHOQOL-BREF, which is a 26-item version of the WHOQOL-100 assessment. The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire was developed in the context of the four domains defining the QOL: physical, psychological, social, and environmental. The higher the QOL score the higher the life satisfaction.

10

Stress was measured using SRI, which is a 39-question multiple-choice self-report inventory for measuring the severity of stress over a week. It was developed in the context of seven domains: anxiety, aggression, somatization, anger, depression, fatigue, and frustration. It was evaluated on a 6-point scale, with 5 being very stressful and 0 being least stressful; higher scores reflected higher stress levels.

11

Resilience was measured using CD-RISC. The CD-RISC comprised 25 items, each rated on a 5-point scale (0-4), with higher scores reflecting higher resilience.

12

Statistical analysis

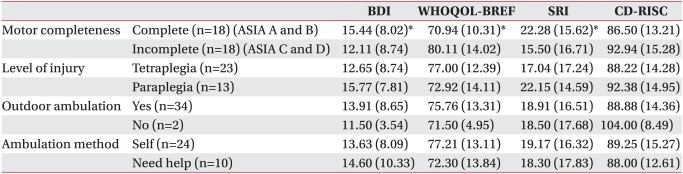

We used Mann-Whitney U tests to compare BDI, WHOQOL-BREF, SRI, and CD-RISC scores according to demographic and function-related characteristics, such as gender, etiology, marital status, type of spinal cord injury (level of injury and completeness of injury), and ambulation ability and to compare the characteristics between the nondepressive and depressive groups.

A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS for Windows version 19.0.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that patients with SCI suffered a higher rate of depression (63.9%) and higher overall level of depression (13.8 points) within 6 months of the occurrence of the SCI. It was also found that motor complete injuries had significant effects on depression, QOL, and stress levels. Moreover, we found that the married patients had poorer QOL scores when compared with the unmarried group, while the depressive group had a lesser lower-extremity AMS score of when compared with the nondepressive group.

One of the important findings in this study was a high overall prevalence of depression. The average BDI score was 13.8, representing a mild depressive state using a BDI cut-off score of 10 for depression. Overall, the rate of depression was higher in the current study, with 23 patients (63.9%) showing signs of depression, when compared with earlier studies, with approximately 19% to 35% of patients showing clinically significant symptoms of depression 10 years after the SCI.

13,

14

The higher rates of depression in this study may reflect several factors. One factor could be that our group comprised patients who had been injured within the last 6 months, whereas earlier studies included participants who had been injured any time within the last 1 to 10.6 years.

15,

16

The relationship between the period of time since sustaining the SCI and the onset of depression is complex. The depression scores were highest in patients who had lived the least number of years since the SCI happened and in those with the most number of years since the SCI. The high levels of depression among the most recently injured patients may reflect the adjustment process itself. In contrast, high depression levels in patients who lived the longest with the SCI may be because of their response to other changes, such as the onset of secondary conditions as a result of aging.

3 Earlier studies presented that BDI scores showed a gradual increase until 48 weeks after the SCI.

17 This may explain the reason for which the depression rate is higher in this study compared with the results from other studies described earlier.

Another potential factor is that all patients in this study were investigated under hospital admission. Prospective, longitudinal research on depression among SCI patients had been done on periods ranging from initial contact of hospitalization to 2 years postdischarge to the community. The BDI scores were highest in the early stage of the SCI and during the months leading up to the discharge from the hospital. After the discharge from the hospital, a significant reduction in mean BDI scores were observed.

18

In our study, married patients were less satisfied with their lives compared with the unmarried patients. DeVivo and Fine

19 concluded that patients with SCIs experienced fewer marriages and more divorces when compared with their noninjured counterparts. Moreover, divorcing patients were significantly more likely to be young women who had been previously divorced, had no children, and had Barthel scores of less than 80.

The people in our study group classified as married were still together with their partners, and most of them were cared for by their partners or other family members. As all the patients studied were in-patients at the hospital, they were not the earning members of their respective families. The unmarried people in our study group were less unsatisfied with their lives, whereas married persons were more unsatisfied because they were experiencing the pressure of not being able to normally function in the household.

In our study, motor incomplete SCI patients were less depressed, had more life satisfaction, and experienced lesser stress levels. These results suggest that the capability to move a part of the body can make people less depressive and more satisfactory, even if it is insufficient to walk without assistance, especially in the early period of rehabilitation. This may also be attributed to the fact that motor incomplete SCI patients expect to recover their motor functions in the near future.

In this study, we also found that the depressive group had lesser lower-extremity AMS. Typically, individuals who experience an SCI are initially focused on walking without assistance, and this is the reason that most research focus on ambulation-related goals. In earlier studies, the change in the method of mobility consistently proved to be a significant predictor of QOL.

20 The patients who went from unassisted walking to wheelchair ambulation showed lower life satisfaction and higher depression levels. Earlier studies also showed that QOL is directly related to effective mobility, especially because it permits involvement in community activities.

21

Even though other powerful factors for ambulatory ability such as AMI were not correlated with depression or life satisfaction in our study, this may be the reason that AMI scores of both groups did not consider ambulation. These results indicate that the capability to move one's legs could make people less depressed, especially in the early period of rehabilitation, even if it is insufficient to walk without assistance.

A recent study has reported psychological variables (e.g., mood, cognition, and coping strategies) as contributing factors when explaining such variance in functional independence.

7 A further study found a relationship among mood, coping style, and functional outcome, while positive coping and getting on with life were significantly related to functional outcome in 228 of the patient participants.

22

However, there was no relationship between depression and functional independence assessment tools such as MBI, FIM, and SCIM in our study. Our study group comprised patients injured within the last 6 months, which might be too early to evaluate final functional independence. In addition, patients were under functional training in this period, during which there could be an underestimation of functional independence.

This study is significant as it is the first study to evaluate the severity of depression and degree of life satisfaction in SCI patients in the early stages of rehabilitation in Korea. However, it bears several limitations. The first limitation of this study is the small number of participants, as we evaluated the condition of SCI patients within the first 6 months after the SCI.

The second limitation is that we did not compare results between patients who were injured within the last 6 months with those injured during the period more than 6 months. The third is that we did not investigate socioeconomic aspects such as occupation, education, and income and effects of usage of antidepressants.

PDF

PDF ePub

ePub Citation

Citation Print

Print

XML Download

XML Download